William Strang stands as a significant figure in British art history, bridging the late Victorian era and the early 20th century. A prolific Scottish artist, he achieved renown primarily as an etcher and printmaker, yet also cultivated a substantial career as a painter, particularly of portraits. His work is characterized by technical mastery, a commitment to realism, and a profound psychological depth, exploring themes ranging from the pastoral and biblical to stark social commentary. As a student of Alphonse Legros and a key participant in the Etching Revival, Strang carved a unique path, leaving behind a vast and varied body of work that continues to command respect and interest.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Dumbarton, Scotland, on February 13, 1859, William Strang's initial path seemed destined for industry rather than art. His early employment was in the counting house of a firm of shipbuilders, a common trajectory for young men in the bustling shipbuilding region of the Clyde. However, the lure of art proved stronger than the demands of commerce. Recognizing his burgeoning talent and ambition, Strang made the pivotal decision to leave the shipyard behind and pursue formal artistic training.

In 1875, at the age of sixteen, he traveled south to London, the vibrant heart of the British art world. This move marked a definitive break from his previous life and the beginning of his dedicated journey into art. London offered opportunities unavailable in Scotland at the time, particularly access to premier art institutions and exposure to a dynamic community of artists and ideas. His enrollment at the prestigious Slade School of Art would prove transformative, setting the stage for his future accomplishments.

The Slade School and the Influence of Legros

The Slade School of Art, part of University College London, was a crucible of artistic innovation and rigorous training. Under the directorship of Edward Poynter and later, more significantly for Strang, under the tutelage of Alphonse Legros, the Slade emphasized draughtsmanship and the study of Old Masters. Legros, a French artist who had settled in England, brought with him the traditions of French Realism, having been associated with figures like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet, though his own style was more aligned with the somber dignity of the Old Masters he revered.

Legros became the Slade Professor in 1876, shortly after Strang's arrival. He was not only a painter and sculptor but also a passionate advocate for etching, a medium whose status as a fine art he sought to restore. Strang quickly distinguished himself as a gifted student, absorbing Legros's emphasis on strong drawing, anatomical accuracy, and expressive line. The master recognized the young Scot's potential, particularly in the demanding discipline of etching.

So proficient did Strang become that Legros appointed him as his assistant in the etching class in 1880. This position provided Strang with invaluable hands-on experience and further cemented his technical foundation. The relationship between mentor and student was profound; Legros's artistic philosophy, his technical methods, and his dedication to printmaking deeply shaped Strang's early career and artistic outlook. Strang inherited Legros's respect for craftsmanship and his belief in the expressive power of the etched line.

Mastery of Etching: Technique and Themes

Emerging from the Slade, William Strang rapidly established himself as one of the foremost etchers of his generation. He was a founding member of the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers (RE) in 1880, an organization dedicated to promoting original printmaking. His technical facility was remarkable; he mastered not only etching but also drypoint, mezzotint, and engraving, often combining techniques to achieve rich tonal effects and textural variety. His linework was confident and expressive, capable of conveying both delicate detail and powerful emotion.

Strang's subject matter in printmaking was exceptionally diverse. He explored landscapes, often imbued with a sense of rustic realism or brooding atmosphere. Pastoral scenes, sometimes recalling the idyllic yet melancholic visions of Giorgione, were frequent themes. Biblical narratives and allegorical subjects allowed him to delve into profound questions of faith, morality, temptation, and mortality, often with a stark, unsentimental approach. His illustrations for works like John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress and Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner demonstrate his ability to translate complex literary ideas into compelling visual form.

Influences from Old Masters are evident throughout his graphic work. The dramatic chiaroscuro and psychological intensity of Rembrandt van Rijn were constant touchstones. The meticulous detail and linear precision of Albrecht Dürer also find echoes in Strang's prints. Yet, his work was not merely derivative. He absorbed these influences into a distinctly personal style, marked by a certain ruggedness, a psychological acuity, and often an unsettling, ambiguous mood that was entirely his own. He was also aware of contemporaries, drawing inspiration from the peasant subjects of Millet and the urban visions of Charles Méryon.

Representative Prints and Social Commentary

Strang's output in printmaking was prodigious, numbering over 750 plates by the end of his life. Several works stand out as particularly representative of his concerns and style. The Tinkers (1882), an early etching, exemplifies his interest in social realism, depicting itinerant workers with an unvarnished honesty that avoids romanticization. It reflects an engagement with the lives of ordinary, often marginalized, people that would recur throughout his career.

Mealtime (also known as Grace), another significant early print, portrays a humble family gathered for a meal. The composition blends the rustic realism associated with Legros and Millet with a palpable sense of tension and quiet drama. The figures are rendered with solidity, but the atmosphere is charged, hinting at unspoken thoughts or hardships. Critics noted the fusion of influences – the pastoralism perhaps nodding to Giorgione, the somber light recalling Rembrandt – yet synthesized into Strang's unique, slightly unsettling vision.

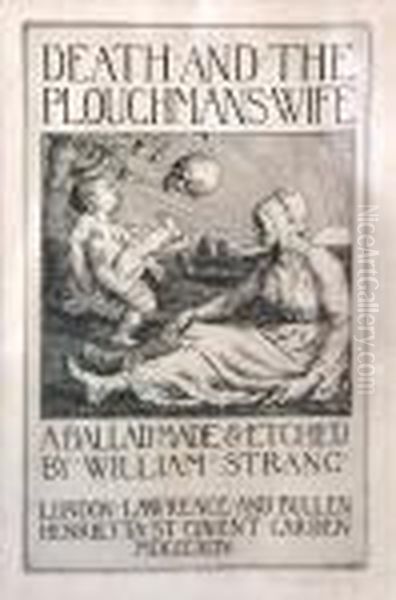

His allegorical and imaginative works often carried a powerful, sometimes macabre, charge. Prints like Death and the Ploughman's Wife explore universal themes with a directness that can be startling. Fantastical subjects, such as The Whale Rider (1892) or The Giant (1882), showcase his imaginative power and his ability to create compelling, dreamlike imagery. These works often possess a narrative ambiguity that invites interpretation, engaging the viewer on an intellectual and emotional level. Strang's commitment to portraying life's struggles, whether material or spiritual, remained a constant thread.

The Shift Towards Painting: Portraits and Beyond

While etching remained a central pillar of his artistic practice throughout his life, William Strang increasingly turned his attention towards painting, particularly from the 1890s onwards. This shift may have been motivated by various factors, including the potentially greater financial rewards and public prestige associated with painting, especially portraiture, in the established art hierarchy of the time. He sought recognition within the Royal Academy, where painting held precedence over printmaking.

His approach to painting retained the emphasis on strong drawing and realism that characterized his prints. He did not embrace the looser brushwork and brighter palettes of Impressionism or Post-Impressionism in a wholesale manner, though elements of contemporary movements can sometimes be discerned in his later works. His primary focus in painting became portraiture, a genre where his skills in capturing likeness and conveying psychological depth could be fully expressed.

Beyond portraits, Strang also produced subject paintings, often exploring similar themes to his etchings – biblical scenes, allegories, and depictions of rural life. Works like Bank Holiday (1912, Tate), depicting working-class Londoners enjoying a day out, show his continued interest in social observation, rendered with a solidity and attention to character that connects his painted work back to his graphic art roots. He experimented with different scales and compositions, demonstrating versatility beyond the intimate format of most etchings.

Notable Portraits and Painting Style

William Strang became a sought-after portrait painter, capturing the likenesses of many prominent figures of the Victorian and Edwardian eras. His sitters included writers, artists, academics, and members of society. His portrait style was generally characterized by its directness, solid modeling of form, and keen psychological insight. He aimed not just for a superficial likeness but for a deeper sense of the sitter's personality and presence.

Among his most famous portrait subjects was the writer Thomas Hardy, whom Strang depicted multiple times in drawings and etchings. These portrayals are noted for their rugged honesty and empathy, capturing the weathered features and thoughtful demeanor of the novelist. His portraits of fellow artists, such as Charles Shannon, or writers like Henry Newbolt and Laurence Binyon, often convey a sense of intellectual connection and shared milieu. He also painted striking portraits of women, including a notable depiction of the writer Vita Sackville-West.

Strang worked adeptly in various portrait media. His oil portraits are often characterized by their sober palettes and strong construction. His pencil and chalk drawings, frequently executed with remarkable precision and sensitivity, were highly praised. Some critics compared the incisive quality of his pencil portraits to the literary character studies of Thomas Hardy himself. His pastel portraits were admired for their subtlety and delicate handling of color and tone. His numerous self-portraits, created throughout his career, offer a fascinating record of his own intense, observant gaze and evolving self-perception.

Influences and Artistic Dialogue

Strang's artistic development was shaped by a rich dialogue with both past masters and contemporary currents. The foundational influence of Alphonse Legros, emphasizing draughtsmanship and the gravitas of the Old Masters, remained paramount throughout his career. The towering figures of Rembrandt and Dürer provided enduring models for technical excellence and expressive power in printmaking, while Giorgione offered inspiration for pastoral mood.

He was not immune to contemporary developments. While not an Impressionist, he was certainly aware of the movement and its aftermath. There are suggestions, particularly in some later paintings, of an interest in the bolder colors and simplified forms associated with Post-Impressionism. Mentions of artists like Paul Gauguin or the Swiss symbolist Ferdinand Hodler in relation to Strang suggest an awareness of broader European trends, even if his core style remained rooted in realism and strong linear structure.

Within the British art scene, Strang occupied a distinct position. He was a central figure in the Etching Revival, alongside Legros, Sir Francis Seymour Haden, and, in a different stylistic vein, James McNeill Whistler. While sharing their goal of promoting original etching, Strang's style differed significantly from Whistler's atmospheric aestheticism or Haden's looser landscape approach. He maintained friendships and professional connections with many artists, including fellow Slade alumni like William Rothenstein and figures associated with the Symbolist movement like Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon.

Role in the Etching Revival

The Etching Revival was a crucial movement in late 19th-century British art, seeking to reclaim etching from its status as a primarily reproductive medium and re-establish it as a vital form of original artistic expression. William Strang was at the very heart of this movement from its early stages. His training under Legros, a key proponent of the revival, positioned him perfectly to become one of its leading practitioners.

His co-founding of the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers (RE) in 1880 was a landmark event. The Society provided a dedicated platform for exhibiting and promoting original prints, challenging the dominance of painting within institutions like the Royal Academy. Strang's prolific output and technical brilliance served as a powerful example of the artistic possibilities of etching and related intaglio techniques. He demonstrated that printmaking could tackle ambitious themes with the same seriousness and depth as painting.

Furthermore, Strang contributed to the theoretical and practical understanding of the medium. He collaborated with H.W. Singer on the book Etching, Engraving and the Other Methods of Printing Pictures (1897), a significant technical manual. His own practice, rigorously documented and widely exhibited, helped educate both fellow artists and the public about the nuances and artistic potential of printmaking. His dedication ensured that the revival was not merely about technique, but about asserting the creative autonomy of the printmaker.

Professional Affiliations and Recognition

Throughout his career, William Strang actively participated in the institutional structures of the London art world, achieving significant recognition. His early involvement with the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers marked the beginning of a long association with artistic societies. His skill eventually garnered attention from the more conservative Royal Academy of Arts (RA).

He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1906, a significant step for an artist primarily known, at that point, for his printmaking. This election acknowledged his growing stature within the British art establishment. He continued to exhibit paintings and prints at the RA's annual exhibitions. His ultimate recognition came posthumously, or nearly so: he was elected a full Royal Academician (RA) in early 1921, but died before he could formally receive the diploma, passing away in April of that year.

Strang was also involved with the more progressive International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers (IS), which had been presided over by Whistler and later Auguste Rodin. Strang served as the society's President from 1918 until his death in 1921, demonstrating his standing among a more cosmopolitan group of artists. His work received international accolades as well, including a Silver Medal at the Exposition Universelle in Paris (1889) and a Gold Medal at the International Exposition in Dresden (1897), confirming his reputation beyond British shores.

Later Life and Legacy

William Strang remained artistically active until the end of his life. He continued to produce etchings and paintings, including numerous portraits, maintaining his characteristic vigour and technical skill. His presidency of the International Society kept him engaged with the contemporary art scene. His sudden death from heart failure on April 12, 1921, in Bournemouth, at the age of 62, cut short a still-productive career.

His legacy was carried on immediately by his two sons, Ian Strang (1886-1952) and David Strang (1887-1967), who both became accomplished printmakers and painters in their own right, working in styles clearly influenced by their father's example. David Strang also became a master printer, responsible for printing plates by his father and other notable etchers.

Today, William Strang's works are held in major public collections worldwide, including the Tate Britain, the British Museum, the National Portrait Gallery in London, the Scottish National Gallery, Glasgow Museums, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, among many others. His contribution to the Etching Revival is undisputed, and his prints are studied for their technical mastery and thematic depth. His portraits remain powerful documents of his era and testaments to his skill in capturing human character.

Critical Reception and Historical Standing

During his lifetime, William Strang enjoyed considerable success and respect. He was regarded as a master technician in etching, and his portraits were generally well-received. However, his position in art history has seen some fluctuation, and his critical evaluation is not without complexity. While acknowledged for his skill and productivity, his adherence to realism sometimes led to criticism, particularly as Modernist movements gained ascendancy in the early 20th century.

Some critics found his style overly reliant on his predecessors, particularly Legros and the Old Masters, suggesting a lack of radical innovation compared to more avant-garde contemporaries. His painting style, while strong, was occasionally deemed conservative or inconsistent, perhaps lacking the singular vision found in his best graphic work. The very seriousness and sometimes somber or unsettling nature of his themes might also have limited his popular appeal compared to artists with a lighter touch.

Despite these critiques, Strang's importance remains undeniable. He was a pivotal figure in sustaining and elevating the art of original printmaking in Britain. His work provides a fascinating bridge between 19th-century realism and the changing artistic landscape of the early 20th century. His portraits offer invaluable insights into the personalities of his time, rendered with an honesty and psychological penetration that transcends mere likeness. Recent scholarship and exhibitions have helped to reaffirm his status as a significant and multifaceted artist whose work merits continued attention and appreciation.

Conclusion

William Strang was an artist of formidable talent and unwavering dedication. From his beginnings in Scotland and formative training under Legros at the Slade, he forged a career marked by exceptional technical skill, particularly in etching, and a profound engagement with the human condition. As a master printmaker, he explored a vast range of subjects with realism, psychological depth, and imaginative power, playing a crucial role in the Etching Revival. As a painter, he created compelling portraits that captured the essence of his sitters and documented an era. Though sometimes viewed through the lens of the artistic revolutions that followed him, Strang's substantial body of work, his influence as a teacher and advocate for printmaking, and his unique artistic voice secure his place as a major figure in British art history. His art continues to resonate through its technical brilliance, its emotional honesty, and its enduring exploration of life's complexities.