Robert Leopold Leprince (1800-1847) stands as a notable, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French landscape painting. Active during a period of profound artistic transformation, Leprince carved out a distinct niche for himself with his sensitive portrayals of the French countryside, particularly its sylvan charms and rustic simplicity. His work, characterized by meticulous observation, a nuanced understanding of light, and a quiet poetry, offers a valuable window into the evolving aesthetics of landscape art before the full ascendance of Impressionism.

An Artistic Lineage and Early Formation

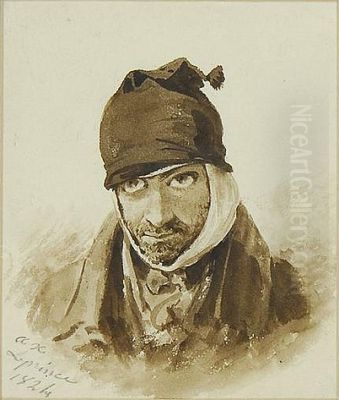

Born in Paris in 1800, Robert Leopold Leprince was immersed in art from his earliest years. He hailed from a family of painters, a common and often beneficial circumstance for aspiring artists of the era. His father, Anne-Pierre Leprince, was an artist, and his elder brother, Auguste-Xavier Leprince (1799-1826), also pursued a career as a painter, achieving considerable recognition before his tragically early death. This familial environment undoubtedly provided Robert Leopold with his initial artistic instruction and fostered a deep appreciation for the craft.

The Leprince brothers, including Robert Leopold and Auguste-Xavier, are known to have worked together, possibly in a shared studio space. Sources indicate their association with the "La Childebert" workshop in Paris. Furthermore, Robert Leopold took on the role of mentor for his younger brother, Gustave Leprince, ensuring the continuation of the family's artistic pursuits. This close-knit artistic upbringing would have exposed him to various contemporary trends and techniques, shaping his early development. He eventually chose to settle in Chartres, a city whose surrounding landscapes likely provided ample inspiration.

Navigating the Parisian Art World: The Salon and Recognition

The Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the paramount venue for artists seeking recognition and patronage in 19th-century France. To exhibit at the Salon was a mark of professional validation. Robert Leopold Leprince successfully navigated this competitive arena, regularly submitting his works for consideration. His talent did not go unnoticed; in 1824, he was awarded a silver medal at the Salon, a significant honor that would have enhanced his reputation and attracted potential buyers.

Beyond Paris, Leprince's paintings were also exhibited in several provincial cities, including Toulouse, Douai, Lille, and Clermont-Ferrand. This broader exposure indicates a growing demand for his work and his active participation in the national art scene. His ability to capture the specific character of French regional landscapes resonated with audiences both in the capital and beyond.

The Essence of Leprince's Art: Style and Subject Matter

Robert Leopold Leprince was, above all, a painter of landscapes and rural scenes. He possessed a keen eye for the subtleties of the natural world, particularly the play of light and atmosphere. His canvases often depict tranquil woodland interiors, sun-dappled clearings, rustic farmyards, and pastoral vignettes featuring peasants or animals. There is an intimacy and sincerity in his approach, a desire to convey the quiet beauty of everyday rural life and the enduring presence of nature.

His technique was characterized by careful draftsmanship and a refined application of paint. Leprince was particularly adept at rendering foliage, employing a rich palette of greens to capture the varied textures and tones of leaves and undergrowth. A distinctive aspect of his method, noted by observers, was his practice of applying touches of white paint to tree branches and trunks. This was not merely a stylistic quirk but a deliberate means of suggesting the reflection of light, thereby imbuing his scenes with a greater sense of luminosity and vibrancy. This attention to the optical effects of light prefigures, in a modest way, some of the concerns that would later preoccupy the Barbizon School painters and the Impressionists.

Leprince's commitment to direct observation is evident. He frequently painted in the Forest of Fontainebleau, a locale that became a crucible for landscape painters in the 19th century. This practice of working en plein air, or outdoors, at least for preparatory studies, was gaining traction. Artists like Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes and Jean-Victor Bertin had earlier championed the oil sketch made directly from nature, and this tradition was being carried forward by Leprince's generation.

Key Works: Capturing the Spirit of Place

Several works by Robert Leopold Leprince exemplify his artistic concerns and stylistic strengths.

La Cour des Dîmes à Provins (The Tithe Barn at Provins), 1824: Exhibited at the Salon of 1824, the year he received his medal, this painting likely showcases his ability to combine architectural elements with landscape. Provins, a medieval town, would have offered picturesque motifs. The depiction of a tithe barn suggests an interest in rural heritage and the textures of aged structures integrated within their natural surroundings.

Berger et son troupeau dans la ruelle (Shepherd and his Flock in an Alley), 1826: This title evokes a pastoral scene, a common theme in 19th-century art that idealized rural life. Leprince's treatment would likely have focused on the harmonious relationship between the shepherd, his animals, and the rustic setting, perhaps with an emphasis on the light filtering through the lane.

Study of Trees (c. 1820): Now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, this oil sketch on paper laid down on canvas is a testament to his dedication to direct observation. It reveals his skill in capturing the individual character of trees, their branching structures, and the texture of their bark and foliage. Such studies were crucial for building a visual vocabulary that could be incorporated into more finished studio compositions. The work demonstrates a fresh, unmediated response to nature.

Farm Courtyard (c. 1820): Similar to Study of Trees, this work likely emphasizes the charm of rural architecture and the daily life unfolding within it. Leprince's eye for detail would have captured the textures of stone and wood, the play of sunlight and shadow in the yard, and perhaps figures engaged in simple tasks.

Sous-bois (Intimate Woodland / Forest Interior), 1829: Housed in the Fondation Custodia, Paris, this painting, likely created in the Forest of Fontainebleau, exemplifies his love for woodland scenes. It probably features a dense arrangement of trees, with light filtering through the canopy to illuminate the forest floor. Such works often convey a sense of solitude and immersion in nature, inviting the viewer to step into the tranquil space. The depiction of a winding stream within a secluded part of the forest, with trees showing the fresh green of late spring, highlights his intimate connection with the natural world.

Repas des vendangeurs près de Tours (Meal of the Grape Harvesters near Tours), 1835: This work, exhibited at the Paris Salon, points to his interest in genre scenes within a landscape setting. The depiction of grape harvesters taking a meal would have allowed him to explore figurative painting while situating the scene within a specific regional context, that of the Loire Valley, known for its vineyards.

These works, and others like them, reveal Leprince as an artist deeply attuned to the nuances of the French landscape. He was not a painter of grand, dramatic vistas in the tradition of some Romantic painters, but rather a chronicler of its more intimate and accessible beauties.

Leprince in the Context of His Contemporaries

Robert Leopold Leprince worked during a vibrant and transitional period in French art. The Neoclassical tradition, with its emphasis on idealized landscapes epitomized by artists like Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes in his theoretical writings and some of his finished works (though his oil sketches were revolutionary), was gradually giving way to Romanticism and the rise of a more naturalistic approach to landscape.

Leprince's focus on direct observation and the specific character of French scenery aligns him with a broader movement towards naturalism. He can be seen as a precursor to, and contemporary of, the Barbizon School painters. While he may not have been a formal member of this group, his frequent sojourns in the Forest of Fontainebleau and his dedication to capturing its unique atmosphere place him in their artistic orbit. Artists like Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, Charles-François Daubigny, Jules Dupré, Constant Troyon, and Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña, who formed the core of the Barbizon School, shared Leprince's commitment to painting directly from nature and imbuing their landscapes with a sense of truthfulness. Camille Corot, a towering figure whose career spanned this entire period, also championed plein air painting and a lyrical interpretation of nature, and his influence was pervasive.

Compared to the dramatic Romanticism of Eugène Delacroix or Théodore Géricault, Leprince's art is more subdued and introspective. His landscapes do not typically feature turbulent skies or sublime, awe-inspiring scenery. Instead, they offer a quieter, more contemplative vision of nature. He shared with artists like Paul Huet an interest in the varied terrains of France and a desire to capture their specific moods.

The generation preceding Leprince, including landscape specialists like Jean-Victor Bertin and Achille-Etna Michallon (Corot's teacher), had already begun to shift the focus towards more naturalistic depictions, even within the framework of the paysage historique (historical landscape). Leprince built upon these foundations, further emphasizing the direct study of nature. His work can also be seen as part of a lineage stretching back to 17th-century Dutch landscape painters, whose intimate and realistic portrayals of their own countryside found renewed appreciation in the 19th century, and even to the idealized yet nature-based classical landscapes of Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin, whose compositional principles still informed academic training.

Artistic Techniques and Innovations

Leprince's technique, while not radically innovative in the way that Impressionism would later be, was nonetheless refined and effective for his artistic aims. His careful rendering of details, combined with a sensitive handling of light, created believable and engaging scenes. The aforementioned use of white highlights to simulate reflected light was a subtle but effective device for enhancing the three-dimensionality and luminosity of his forms, particularly trees.

His oil sketches, such as Study of Trees, demonstrate a freshness and immediacy that was characteristic of the growing practice of plein air painting. These studies, often executed on paper or small panels, allowed artists to capture fleeting effects of light and atmosphere that could then inform their larger, more finished studio compositions. This practice was crucial for the development of a more naturalistic landscape art and laid the groundwork for the Impressionists, who would take plein air painting to its logical conclusion by often completing entire canvases outdoors.

The choice of subject matter itself – the unadorned French countryside, the specific character of a forest interior, the rustic charm of a farm – was part of a broader shift away from the idealized Italianate landscapes or grand historical narratives that had previously dominated academic landscape painting. Leprince and his contemporaries were increasingly finding beauty and significance in their native scenery.

Later Years and Premature End

Robert Leopold Leprince's career, though productive, was relatively short. He passed away in 1847 at the age of just 47. This premature death cut short the development of an artist who had already demonstrated considerable talent and had earned a respected place within the French art world. One can only speculate on how his style might have evolved had he lived longer, perhaps engaging more directly with the burgeoning Realist movement championed by artists like Gustave Courbet, or witnessing the early stirrings of Impressionism.

Despite his relatively brief lifespan, Leprince left behind a significant body of work that attests to his dedication and skill. His paintings continue to be appreciated for their quiet beauty, their technical accomplishment, and their sincere engagement with the natural world.

Legacy and Influence

Robert Leopold Leprince's legacy resides primarily in his contribution to the development of 19th-century French landscape painting. His emphasis on direct observation, his sensitive rendering of light and atmosphere, and his focus on the native French countryside helped to pave the way for later movements.

While he may not be as widely known today as some of his Barbizon contemporaries or the subsequent Impressionist masters like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, or Alfred Sisley, Leprince's work holds an important place in the lineage of French naturalism. His paintings offer a bridge between the more formal landscape traditions of the early 19th century and the more radical innovations that were to come.

His influence can be seen in the broader appreciation for plein air painting and the detailed study of nature that characterized much of 19th-century landscape art. Artists who sought to capture the true "feel" of a place, its specific light and atmosphere, were working in a vein similar to Leprince. His dedication to depicting the familiar landscapes of France contributed to a growing national pride in the country's natural beauty.

Today, Robert Leopold Leprince's works are held in the collections of several important museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Fondation Custodia (Collection Frits Lugt) in Paris. Their presence in these institutions ensures that his contribution to art history is preserved and accessible to contemporary audiences. His paintings serve as a reminder of the rich diversity of talent that flourished in 19th-century France and the enduring appeal of landscapes rendered with skill, sensitivity, and a genuine love for the subject.

In conclusion, Robert Leopold Leprince was a gifted and dedicated landscape painter whose art reflects the evolving sensibilities of his time. His intimate and lyrical portrayals of the French countryside, characterized by meticulous observation and a nuanced understanding of light, earned him recognition during his lifetime and continue to resonate with viewers today. As an artist who embraced the direct study of nature and celebrated the beauty of his native land, he played a significant role in the journey of French landscape painting towards greater naturalism and authenticity, a path that would ultimately lead to the revolutionary art of the Impressionists. His art remains a gentle yet persuasive voice from a pivotal era in the history of landscape painting.