James Sidney Edouard Ensor stands as one of Belgium's most significant and enigmatic artists, a pivotal figure whose work bridged the 19th and 20th centuries and laid crucial groundwork for Expressionism and Surrealism. Born in the seaside town of Ostend on April 13, 1860, Ensor's life and art were deeply intertwined with his coastal origins and the peculiar atmosphere of his family's curiosity shop. His canvases teem with masks, skeletons, carnivalesque crowds, and biting satire, creating a unique visual language that continues to fascinate and disturb. He was a painter of light and shadow, of social critique and profound introspection, a true pioneer who dared to confront the absurdities and anxieties of modern life head-on.

Early Life and Coastal Influences

Ensor's background was a curious mix. His father, James Frederic Ensor, was an educated Englishman of independent means who had studied engineering but struggled with personal demons, eventually succumbing to the effects of alcohol and substance abuse. His mother, Maria Catherina Haegemans, was Flemish and the pragmatic force in the family. She ran a curiosity and souvenir shop in Ostend, filled with seashells, chinoiserie, carnival masks, and an assortment of oddities. This shop, located beneath the family's apartment, became young James's unconventional playground and a profound source of inspiration. The bizarre juxtaposition of objects, particularly the masks, would become central motifs in his later work.

The family environment was reportedly not always harmonious, marked by the father's decline and the mother's perhaps stern practicality. Ensor himself showed little interest in formal schooling, leaving traditional education behind at the age of fifteen. Instead, he received early drawing lessons from two local painters. The vibrant, sometimes harsh, environment of Ostend – a popular seaside resort known for its lively carnival tradition – permeated his consciousness. The sea itself, with its changing light and moods, would also become a recurring subject in his early paintings. His sister, Mariette (known as Mitche), and other relatives were also part of this domestic sphere, involved in the family business.

Academic Training and Artistic Beginnings

Despite his aversion to conventional schooling, Ensor pursued formal art training. From 1877 to 1880, he studied at the prestigious Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. Here, he encountered fellow students who would also make their mark, including the Symbolist painter Fernand Khnopff. However, Ensor quickly grew disillusioned with the conservative, academic approach taught at the institution. He found the emphasis on traditional techniques and historical subjects stifling to his burgeoning creativity. He famously clashed with the faculty, rejecting their rigid methods.

Upon completing his studies, Ensor returned to Ostend in 1880, setting up a studio in the attic of his parents' house. His early works from this period, often referred to as his "dark" or "somber" period (roughly 1880-1885), show the influence of Realism and Impressionism. He painted portraits, domestic interiors, landscapes, and still lifes, often featuring his family members, particularly his sister. Works like The Oyster Eater (1882) showcase his early mastery of light and texture, rendered with a rich, somewhat dark palette influenced by artists like Rembrandt and the burgeoning Impressionist movement, perhaps absorbing ideas from painters like Edouard Manet. Yet, even in these relatively conventional works, hints of his later originality began to surface in the psychological intensity and unconventional compositions.

The Emergence of Masks and Skeletons

Around the mid-1880s, a dramatic shift occurred in Ensor's art. He largely abandoned the darker palette and Impressionistic concerns, embracing brighter colors and, most significantly, introducing the motifs that would define his career: masks and skeletons. This transformation was fueled by several factors: his rejection by the official Salons, his growing sense of isolation and persecution by critics, and the deep wellspring of imagery from his mother's shop and Ostend's carnival traditions.

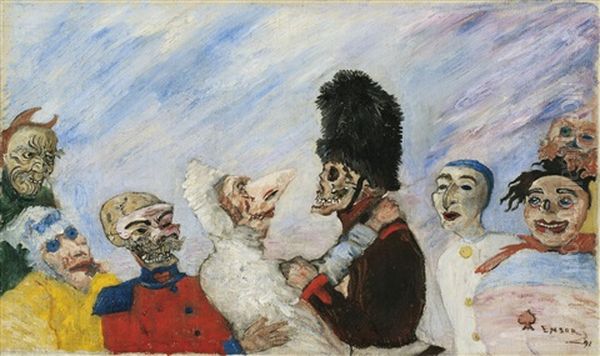

Masks, for Ensor, became powerful symbols of societal hypocrisy, deceit, and the grotesque absurdity of human behavior. They allowed him to strip away social veneers and expose the underlying anxieties, vanities, and cruelties he perceived in the world around him. Skeletons, often depicted engaging in mundane or bizarre activities, served as stark reminders of mortality (memento mori) and frequently stood in for the artist himself or represented humanity stripped bare of pretense. Works like The Intrigue (1890), depicting a tightly packed group of masked figures with unsettling expressions, exemplify his use of these motifs for sharp social commentary, hinting at hidden conspiracies and malicious gossip. Masks Confronting Death (1888) directly pits the artificiality of the mask against the ultimate reality of the skull.

His fascination with the grotesque also drew from Northern European traditions, echoing the fantastical imagery of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, as well as the satirical prints of artists like Honoré Daumier. The influence of Japanese prints (Ukiyo-e), with their bold lines and flat color planes, can also be detected in his compositions. He began using lighter, more vibrant colors, often applied with a freer, more expressive brushstroke, further distancing himself from academic norms.

Magnum Opus: Christ's Entry into Brussels in 1889

Perhaps Ensor's most famous and ambitious work is the monumental Christ's Entry into Brussels in 1889 (painted 1888-89). This vast, chaotic canvas depicts a contemporary carnival procession swarming through the boulevards of Brussels, with a small, almost overlooked figure of Christ riding a donkey near the center. The crowd is a grotesque sea of masked faces, caricatures of political and social figures, military bands, and nonsensical banners ("Vive la Sociale" – Long live the Social [Revolution]).

The painting is a complex and scathing critique of modern society, politics, and religious hypocrisy. Christ's entry is not a moment of spiritual triumph but an event swallowed by the vulgarity, noise, and indifference of the modern mob. Ensor casts himself, implicitly, as the misunderstood Christ figure, ignored or mocked by the establishment. The painting's radical style – its vibrant, almost Fauvist palette, distorted perspectives, and densely packed composition – was as shocking as its subject matter.

Predictably, the work caused a scandal. It was rejected for exhibition even by the avant-garde group Les XX, which Ensor himself had co-founded. The painting remained largely unseen by the public for decades, stored in Ensor's studio. Its rejection deepened Ensor's sense of alienation but also solidified the painting's legendary status as a landmark of modern art, a precursor to the large-scale critical works of 20th-century artists like George Grosz or Max Beckmann.

Les XX and the Avant-Garde Scene

In 1883, Ensor was a key figure in the founding of Les XX (The Twenty), a Brussels-based avant-garde group dedicated to exhibiting progressive art from Belgium and abroad. The group included artists like Fernand Khnopff and Théo van Rysselberghe, and later invited international figures such as Georges Seurat, Paul Gauguin, and Vincent van Gogh to exhibit with them. Ensor initially played an active role, exhibiting regularly with the group. Les XX provided a vital platform for challenging the conservative art establishment.

However, Ensor's relationship with Les XX became increasingly strained. His radical stylistic developments and provocative subject matter, culminating in the rejection of Christ's Entry into Brussels, created friction. He felt misunderstood and persecuted even within this supposedly progressive circle. His satirical prints, such as Doctrinal Nourishment, which mocked King Leopold II and establishment figures, were also deemed too controversial by some members. Although Les XX was influential, internal disagreements eventually led to its dissolution in 1893 (it was succeeded by La Libre Esthétique). Ensor's experiences with the group reinforced his independent, sometimes cantankerous, spirit.

Distinctive Style and Technical Innovation

Ensor's mature style is characterized by several key elements. His use of color became increasingly bold and expressive, often employing jarring juxtapositions and brilliant hues directly from the tube. He abandoned traditional modeling and perspective, flattening space and distorting figures for emotional impact. This radical approach to color and form clearly anticipates Fauvism, influencing artists like Henri Matisse and Pierre Bonnard who admired his liberation of color.

Light was another crucial element. Having grown up by the sea, Ensor was fascinated by its luminous qualities. His paintings often feature a shimmering, almost ethereal light that contrasts sharply with dark, shadowy areas. This dramatic use of chiaroscuro adds to the psychological tension and otherworldly atmosphere of his work. His brushwork was equally innovative – often quick, agitated, and visible, conveying energy and emotion directly, a hallmark of Expressionism.

Ensor was also a prolific and accomplished printmaker, primarily working in etching. His prints often revisited themes from his paintings, allowing him to explore his grotesque and satirical visions with linear intensity. These prints circulated more widely than some of his controversial paintings, helping to spread his influence. His willingness to blend the real and the fantastic, the humorous and the horrifying, marks him as a significant precursor to Surrealism, admired by artists like Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst for his exploration of the subconscious and the irrational.

Recurring Themes and Preoccupations

Beyond masks and skeletons, Ensor's work explored several recurring themes. Social critique remained central; he relentlessly satirized the bourgeoisie, the clergy, doctors, judges, and political figures, viewing them as pompous, hypocritical, and often cruel. His depictions of crowds are rarely celebratory; they often represent the mindless, menacing mob.

Death and decay are pervasive themes, reflecting not only a universal human anxiety but perhaps also his personal experiences and the memento mori tradition. Yet, his treatment of death is often laced with black humor and absurdity, preventing it from becoming merely morbid. The sea and the unique light of Ostend remained constant sources of inspiration, appearing in numerous landscapes and seascapes throughout his career, even amidst his most fantastical compositions.

Self-portraits are another significant genre. Ensor depicted himself frequently, sometimes realistically, but often disguised – as Christ, a skeleton, a pickled herring, or surrounded by his ubiquitous masks (as in the famous Self-Portrait with Masks, 1899). These self-portrayals reveal a complex personality: proud, defiant, sensitive, and acutely aware of his own mortality and his often-embattled position in the art world.

Connections and Contemporaries

While often portrayed as an isolated figure, Ensor was connected to the artistic currents of his time. Through Les XX, he was aware of international developments like Neo-Impressionism (Seurat exhibited with the group) and Symbolism. His friendships, though perhaps few, were significant. The writer and critic Eugène Demolder was a staunch supporter and friend, appearing in some of Ensor's works. He also maintained a long-lasting platonic friendship with Augusta Boogaerts, who often accompanied him.

His influence radiated outwards. The Austrian Symbolist Alfred Kubin was deeply impressed by Ensor's fantastical imagery. German Expressionists, including Emil Nolde, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and members of Die Brücke group, recognized him as a vital precursor. Nolde, Kandinsky, and Max Beckmann are known to have visited him in Ostend later in his life, acknowledging his pioneering role. French Surrealists like André Breton and Paul Éluard also recognized his importance in challenging rationalism and exploring the bizarre. While perhaps not directly interacting with all of them, his work resonated with contemporaries like Edvard Munch, who shared a similar interest in psychological expression and existential anxiety, and even impacted figures as significant as Pablo Picasso in their exploration of masks and expressive distortion.

Later Life, Recognition, and Legacy

Despite the controversies of his earlier career, Ensor gradually gained recognition in the 20th century. He continued to live and work in Ostend, moving into the family house above the curiosity shop after his mother's death in 1915. While some critics argue his most innovative period was between the mid-1880s and the late 1890s, he remained active. He revisited earlier themes, sometimes creating copies or variations of his successful works. He also devoted time to music, composing pieces for a ballet entitled La Gamme d'Amour (The Scale of Love), for which he also designed the sets and costumes. He wrote extensively, publishing articles, speeches, and letters that often revealed his sharp wit and defended his artistic vision.

Honors eventually came his way. In 1903, he was made a Knight of the Order of Leopold. A major retrospective of his work was held in Antwerp in 1921. Perhaps the most significant official recognition came in 1929 when he was named a Baron by King Albert I of Belgium. The same year, Christ's Entry into Brussels was finally exhibited publicly in Brussels to great acclaim. He became a national figure, the "painter of Ostend."

Ensor died in Ostend on November 19, 1949, at the age of 89. He left behind a body of work remarkable for its originality, psychological depth, and fearless critique. His legacy lies in his pioneering role in paving the way for Expressionism and Surrealism. He demonstrated how color, light, and form could be liberated from academic constraints to express inner turmoil and social commentary. His unflinching exploration of the grotesque, the absurd, and the masked nature of human existence continues to resonate.

Ensor in the Art Market

Reflecting his historical significance, James Ensor's works command considerable attention and high prices in the international art market. Major museums worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Getty Center in Los Angeles, and the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, hold significant works. His paintings and prints appear regularly at major auction houses like Sotheby's and Christie's.

Record prices have been achieved in recent years. In 2017, his painting Squelette arrêtant masques (Skeleton Stopping Masks, 1891) sold for over €7.3 million at Sotheby's Paris. Another work, Baptême de masques (Baptism of Masks), fetched over €1 million at Dorotheum in Vienna. In 2016, Skeletons Fighting over a Pickled Herring (1891) achieved .8 million at auction, a testament to the market's appreciation for his key period. Even his prints are highly sought after; a 2018 Christie's sale dedicated to his etchings realized a total of £1.3 million, with works like Les sept péchés capitaux dominés par la mort (The Seven Deadly Sins Dominated by Death) achieving strong results. This market performance underscores Ensor's established status as a major figure in modern European art.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

James Ensor remains a compelling and unique figure in art history. He was a visionary who channeled the anxieties and absurdities of his time into a startlingly original visual language. From the eerie quiet of his early interiors to the cacophonous energy of his masked crowds and the stark confrontations with mortality, his work challenges, provokes, and fascinates. As the "painter of masks," he explored the hidden realities beneath the surface of bourgeois society. As a master of light and color, he pushed the boundaries of painterly expression. As a fearless satirist, he used humor and the grotesque to critique power and hypocrisy. His unsettling visions, born in the seaside town of Ostend, ultimately transcended their local origins to influence the course of modern art, securing his place as a crucial and enduringly relevant artist.