John Wesley Jarvis stands as one of the most colorful and significant figures in early American art. Active during the nascent years of the United States, a period brimming with nationalistic fervor and the forging of a distinct American identity, Jarvis captured the likenesses of a generation of heroes, statesmen, and cultural icons. His life was as vibrant and unconventional as his art was, at its best, insightful and technically proficient. Born on the cusp of the American Revolution's aftermath and working through the first few decades of the 19th century, Jarvis navigated the burgeoning art scene of cities like Philadelphia, New York, and Baltimore, leaving an indelible mark despite a career trajectory that ultimately mirrored the boom and bust cycles of his era. This exploration delves into his origins, artistic development, notable works, eccentric personality, professional relationships, and lasting legacy.

Transatlantic Beginnings and American Roots

The precise year of John Wesley Jarvis's birth is subject to some historical debate, with sources pointing to either 1780 or 1781. He was born in South Shields, England, a coastal town that perhaps instilled in him an early sense of adventure. His familial connections were notable; he was the nephew of John Wesley, the influential theologian and founder of Methodism. This connection, however, did not seem to dictate a path of piety for the young Jarvis, whose later life was characterized more by bohemian exuberance than religious austerity.

His father, a mariner, relocated the family to the United States when Jarvis was a child, around the age of five. They settled in Philadelphia, then the largest city in the fledgling nation and a vibrant cultural and political hub. It was here, amidst the revolutionary echoes and the construction of a new society, that Jarvis spent his formative years. Philadelphia's artistic environment, though still developing, offered more opportunities than many other American cities at the time, boasting figures like Charles Willson Peale and his artistic dynasty. This environment undoubtedly played a role in nurturing Jarvis's nascent artistic inclinations.

Apprenticeship and Early Artistic Formation

Jarvis's formal artistic training began in earnest around 1796, or perhaps slightly later, closer to 1800, when he was apprenticed to the English-born engraver and painter Edward Savage in Philadelphia. Savage, known for his portraits and historical scenes, including a notable group portrait of the Washington family, provided Jarvis with a foundational education in the visual arts. During this apprenticeship, Jarvis would have learned the meticulous techniques of engraving, a skill that demanded precision and a keen eye for detail. He also collaborated with David Edwin, another English engraver who worked for Savage, further honing his skills in this medium.

The training under Savage was not limited to engraving. Jarvis was also exposed to painting, particularly portraiture and the creation of miniatures, which were highly popular at the time. Miniature painting, often on ivory, required a delicate touch and the ability to capture a likeness on a small scale, skills that would serve Jarvis well throughout his career. It was during this period that he also reportedly received some instruction in miniature painting from Edward Greene Malbone, one of America's most celebrated miniaturists. Malbone's refined and elegant style would have offered a sophisticated model for the aspiring artist.

Around 1801 or 1802, after his apprenticeship with Savage concluded, Jarvis moved to New York City. This move marked a significant step in his career, as New York was rapidly growing in commercial and cultural importance. Shortly after arriving, in 1803, he formed a partnership with Joseph Wood, another artist who had also worked with Savage. Their collaboration, which lasted approximately seven years, was a prolific one. Together, Jarvis and Wood produced a range of artworks, including engravings, miniatures, and larger-scale oil portraits. This partnership was crucial for both artists, allowing them to pool their talents, share the workload, and build a client base in the competitive New York art world.

Establishing a Reputation in New York

By 1810, the partnership with Joseph Wood dissolved, and John Wesley Jarvis set out to establish himself as an independent artist. He opened his own studio in New York City, which quickly became a hub of artistic activity and a popular destination for those seeking to have their portraits painted. Jarvis's timing was fortuitous. The city was expanding, wealth was accumulating, and there was a growing demand among the affluent and influential for portraits that could signify their status and preserve their legacy.

Jarvis's personality played a significant role in his success. He was known for his wit, his flamboyant storytelling, and his often eccentric behavior. These traits, while perhaps unconventional, made him a memorable and entertaining figure. His studio was not just a place of artistic production but also a social gathering spot where clients and friends could enjoy his company and his seemingly endless supply of anecdotes. This ability to charm and entertain, coupled with his artistic skill, helped him attract a distinguished clientele.

His reputation was significantly boosted by a major commission from the City of New York to paint a series of full-length portraits of naval heroes from the War of 1812. These monumental works, destined for display in City Hall, cemented Jarvis's status as one of the leading portraitists in the country. The commission was a testament to his skill in capturing not only a physical likeness but also the heroic aura and patriotic spirit associated with these figures. Artists like Gilbert Stuart had earlier set a high bar for official portraiture with his depictions of George Washington, and Jarvis was now stepping into a similar role for a new generation of American heroes.

Artistic Style and Technical Prowess

John Wesley Jarvis's artistic style evolved throughout his career but generally adhered to the prevailing taste for realism, infused with elements of the late Neoclassical and burgeoning Romantic sensibilities. He was particularly noted for his keen understanding of anatomy, a subject he reportedly studied with great interest, even engaging in dissections to deepen his knowledge. This anatomical understanding lent a sense of solidity and lifelike structure to his figures.

His portraits are often characterized by a directness and a focus on the sitter's individual character. While he could produce works of considerable refinement, there was often an unvarnished quality to his likenesses that conveyed a sense of authenticity. He typically employed a relatively straightforward compositional approach, often placing his sitters against plain or subtly rendered backgrounds, which helped to keep the viewer's attention focused on the face and personality of the subject. His contemporary, Thomas Sully, often favored a more overtly Romantic and flattering style, offering a point of comparison in the diverse landscape of early American portraiture.

Jarvis's brushwork could be fluid and confident, particularly in his more successful periods. His color palettes were generally rich and harmonious, with an ability to render flesh tones with vibrancy and depth. He was adept at capturing the textures of fabrics and other materials, adding to the overall realism of his depictions. While perhaps not possessing the consistent psychological depth of a master like John Singleton Copley from a previous generation, or the refined elegance of Gilbert Stuart at his peak, Jarvis, at his best, created portraits that were strong, engaging, and technically accomplished. He worked relatively quickly, a necessity for a painter who relied on a high volume of commissions.

A Gallery of Notables: Key Sitters and Masterpieces

John Wesley Jarvis's oeuvre is a veritable gallery of early 19th-century American society. His sitters included military leaders, politicians, writers, merchants, and other prominent individuals who shaped the nation's course.

Among his most celebrated works are the six full-length portraits of War of 1812 heroes commissioned by the City of New York, including figures like Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, Commodore Isaac Hull, General Jacob Brown, and Commodore William Bainbridge. These grand portraits, executed between 1813 and 1817, showcase Jarvis's ability to handle large-scale compositions and to imbue his subjects with a sense of dignity and command. The portrait of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry (c. 1816) is particularly striking, depicting the hero of the Battle of Lake Erie with a confident stance and a dramatic, windswept sky in the background, hinting at the Romanticism that was beginning to influence American art.

Jarvis also painted numerous literary figures. His portrait of Washington Irving (c. 1809), created early in his independent career, captures the youthful author with a thoughtful and slightly melancholic expression. He also depicted James Fenimore Cooper, another giant of early American literature. These portraits provide invaluable visual records of the individuals who were crafting a distinct American literary voice.

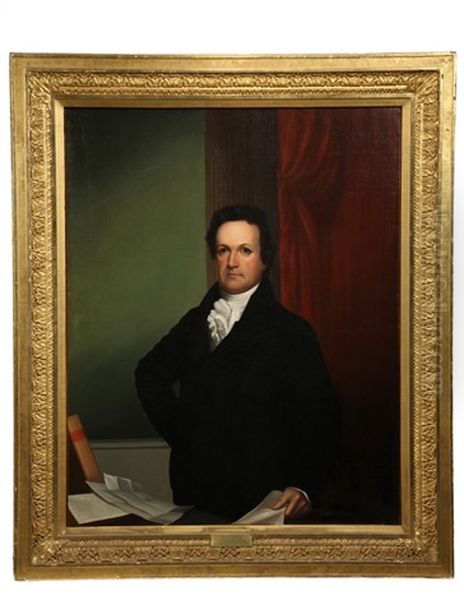

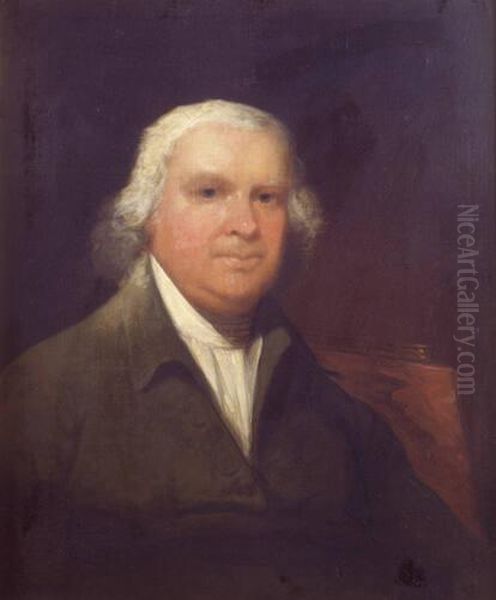

Political figures also frequented his studio. He painted a compelling portrait of John Randolph of Roanoke (c. 1811), the idiosyncratic Virginia congressman, capturing his lean, ascetic features and intense gaze. Later in his career, he would paint Andrew Jackson, a figure who came to define an era. His portrait of DeWitt Clinton, the influential New York governor and a key proponent of the Erie Canal, is another significant work. Other notable sitters included Robert Morris, a financier of the American Revolution, and Ambrose Spencer, a prominent New York jurist.

The quality of Jarvis's work could be uneven, particularly as he often relied on assistants, including his notable pupil Henry Inman, to help with drapery, backgrounds, and even replicas. However, when Jarvis was personally engaged and at the height of his powers, his portraits were formidable. His ability to capture a strong likeness quickly made him a popular choice for those who might not have had the patience for lengthy sittings required by other artists like Rembrandt Peale or Samuel F.B. Morse (before Morse turned his attention to the telegraph).

The Eccentric Artist: Personality and Social Milieu

John Wesley Jarvis was as well known for his flamboyant personality and eccentric lifestyle as he was for his art. He cultivated an image of a bon vivant, known for his extravagant dress, his love of good company, and his prodigious storytelling abilities. William Dunlap, a contemporary artist and America's first art historian, described Jarvis as "the greatest humorist and best storyteller" he had ever met. Jarvis's studio was often filled with laughter and animated conversation, making the experience of sitting for a portrait an entertaining one.

He was a fixture in New York's social scene, moving comfortably among the city's elite. His wit and charm opened doors, but his unconventional behavior also raised eyebrows. He was known for his heavy drinking and a generally dissolute lifestyle, which, while contributing to his bohemian allure, would eventually take a toll on his health and finances. There are numerous anecdotes about his escapades, including his penchant for practical jokes and his sometimes-outlandish pronouncements. For example, he was said to have created humorous caricatures, such as one depicting a barber styling himself as an emperor, a satirical commentary on American egalitarianism versus European monarchical pretensions.

This theatricality extended to his professional life. He understood the importance of self-promotion in a competitive art market. His colorful persona helped to create a buzz around his name, attracting clients who were perhaps as intrigued by the artist as they were by the prospect of obtaining a fine portrait. He was, in many ways, a performer, and his studio was his stage. This contrasts with the more staid and business-like approach of some of his contemporaries, such as the Peale family painters (Charles Willson, James, Raphaelle, and Rembrandt Peale), who emphasized the scientific and educational aspects of art.

Travels and Expanding Horizons

While New York City remained his primary base of operations, John Wesley Jarvis was an itinerant painter, traveling to other cities in search of commissions, a common practice for portraitists of the era. The demand for portraits in any single city could be finite, and artists often needed to tap into new markets to sustain their careers.

He made frequent trips to Baltimore, Maryland, which was a thriving port city with a wealthy merchant class eager for portraiture. His presence in Baltimore put him in the same sphere as other artists who worked there, such as Thomas Sully and Jacob Eichholtz. Jarvis also ventured further south, working in cities like Charleston, South Carolina, and New Orleans, Louisiana. These southern cities, with their plantation economies and distinct cultural milieus, offered lucrative opportunities.

His travels were not always easy. They involved arduous journeys by stagecoach or ship, and he had to set up temporary studios in each new location. However, these excursions broadened his network of patrons and exposed him to different regional tastes and social customs. His ability to adapt and to quickly establish a rapport with new clients was essential to his success as an itinerant artist. The demand for his work in these various locales underscores his national reputation during his peak years.

Mentorship and Influence: Jarvis's Students

John Wesley Jarvis played an important role in training the next generation of American artists. His studio was a lively and, at times, chaotic environment, but it provided valuable hands-on experience for his apprentices.

His most famous student was Henry Inman. Inman joined Jarvis's studio around 1814, at a young age, and remained with him for about seven years. He became an indispensable assistant, often painting backgrounds, draperies, and even entire replicas of Jarvis's portraits. Inman absorbed much from his master, including his fluid brushwork and his ability to capture a likeness. However, Inman also developed his own distinct style, often characterized by a greater degree of refinement and a more Romantic sensibility. After leaving Jarvis, Inman went on to become one of America's leading portrait painters in the 1830s and 1840s, also excelling in genre scenes and miniature painting. His success is a testament to the foundational training he received from Jarvis. Other artists who became known for miniature painting, like Nathaniel Rogers (a student of Joseph Wood) and Thomas Seir Cummings (a student of Inman), were part of this interconnected web of New York artists.

Jarvis's own son, Charles Wesley Jarvis, also became a painter, presumably learning from his father. While Charles did not achieve the same level of fame as Henry Inman, he continued the family's artistic tradition, working primarily as a portraitist. John Quidor, known for his imaginative and often grotesque scenes from American literature, also reportedly spent some time in Jarvis's studio, though his artistic path diverged significantly from portraiture.

The master-apprentice system was still the primary mode of artistic education in America at this time, as formal art academies were few and often struggling. Jarvis's studio, therefore, served as an important training ground, contributing to the development of American art in the early to mid-19th century.

Later Years and Declining Fortunes

Despite his considerable success in the 1810s and early 1820s, John Wesley Jarvis's career began to decline in his later years. Several factors contributed to this downturn. His notoriously intemperate lifestyle, particularly his heavy drinking, began to affect his health and his ability to work consistently. As his physical and mental faculties waned, the quality of his painting suffered. His later works often lack the vigor and technical assurance of his earlier portraits.

The art world was also changing. New artistic trends were emerging, and a younger generation of painters, including his former pupil Henry Inman, was rising to prominence. Competition among portraitists remained fierce. Jarvis, once a leading figure, found it increasingly difficult to secure commissions.

Financial difficulties plagued his later years. Despite earning substantial sums during his peak, his extravagant spending habits and lack of financial prudence left him vulnerable. He reportedly fell into poverty and was supported in his final years by friends and family. His first wife had died relatively young, after bearing him his son Charles. He married a second time, to Betsy Burtsis, but she also predeceased him.

John Wesley Jarvis died in New York City on January 12 or 14, 1839 (some sources say 1840, but 1839 appears more frequently in recent scholarship, aligning with the user's initial information). He was in his late fifties. His death marked the end of a vibrant and tumultuous career. He passed away in relative obscurity, a stark contrast to the fame and adulation he had enjoyed in his prime.

Legacy and Enduring Impact

John Wesley Jarvis's legacy is complex. At his best, he was a highly skilled and insightful portraitist who created enduring images of some of the most important figures of his time. His portraits of the War of 1812 heroes remain iconic representations of American valor. His depictions of writers, politicians, and socialites offer a valuable visual record of the early American Republic. He was a key figure in the New York art scene for over two decades, contributing to its growth and vitality.

He was also a significant mentor, most notably to Henry Inman, who became a leading artist in his own right. Through his students, Jarvis's influence extended into the next generation of American painters. His emphasis on anatomical understanding and his direct, often unembellished, approach to likeness influenced the course of American portraiture.

However, his legacy is also shadowed by the unevenness of his later work and the sad circumstances of his decline. His flamboyant personality and eccentricities, while contributing to his contemporary fame, sometimes overshadowed his artistic achievements in historical accounts. William Dunlap's "History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States" (1834), while providing invaluable information, also painted a picture of Jarvis that emphasized his quirks, perhaps to the detriment of a more balanced assessment of his artistic contributions.

Today, John Wesley Jarvis is recognized as an important, if somewhat mercurial, figure in the history of American art. His works are held in major museum collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, the New-York Historical Society, and various city art galleries. Art historians continue to study his life and work, seeking to understand his place within the broader context of early American culture and the development of a national artistic identity. He remains a fascinating example of an artist whose life and art were deeply intertwined with the spirit of his age – a period of bold experimentation, rugged individualism, and the forging of a new nation. His contributions, both as a painter and a personality, ensure his place in the annals of American art.

Conclusion

John Wesley Jarvis was more than just a painter; he was a phenomenon in the early American art world. From his English birth and Philadelphia upbringing to his rise as New York's premier portraitist and his eventual decline, his life was a tapestry of artistic brilliance, personal eccentricity, and profound engagement with the figures who defined his era. His canvases captured the faces of a nation in its youth, from war heroes like Oliver Hazard Perry and Andrew Jackson to literary giants like Washington Irving. Through his tutelage of artists like Henry Inman, his influence rippled outwards. While his later years were marked by hardship, the body of work he produced at his peak stands as a vital contribution to American art, offering a vivid, insightful, and often spirited glimpse into the personalities and aspirations of the early Republic. His legacy, like the man himself, is multifaceted and enduring.