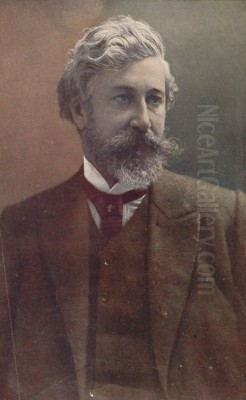

Santiago Rusiñol i Prats stands as a towering figure in Spanish and Catalan culture at the turn of the 20th century. Born in Barcelona on February 25, 1861, and passing away in Aranjuez on June 13, 1931, Rusiñol was far more than just a painter. He was a prolific poet, a successful playwright, a keen-eyed writer, an avid collector, and a central catalyst for the vibrant cultural movement known as Catalan Modernisme. His life and work embody the spirit of an era seeking renewal, beauty, and a modern identity rooted in local tradition yet open to international currents. Rusiñol’s art, particularly his evocative landscapes and garden scenes rendered in a Post-Impressionist style infused with Symbolist melancholy, continues to resonate with audiences today.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Barcelona

Santiago Rusiñol was born into prosperity. His family belonged to the affluent Catalan industrial bourgeoisie, having established a significant textile manufacturing business tracing back generations. His grandfather, Jaume Rusiñol, was also known for diversifying the family's interests. The expectation was clear: Santiago, like his forebears, would dedicate his life to the family enterprise. However, the young Rusiñol felt a different calling, one that pulled him away from the looms and ledgers towards the expressive potential of art.

Despite the predictable path laid out for him, Rusiñol nurtured his artistic inclinations. He began his formal training in Barcelona at the Centre d'Aquarel·listes (Center of Watercolorists). There, he studied under Tomás Moragas, a painter known for his Orientalist themes, which perhaps offered Rusiñol an early glimpse into worlds beyond the familiar Catalan landscape. This initial training provided him with foundational skills, but his artistic vision yearned for broader horizons and deeper engagement with contemporary European art movements. The tension between familial duty and personal passion defined his early adulthood, culminating in his decisive break from the family business around 1887-1888 to dedicate himself fully to art.

The Parisian Crucible: Montmartre and Modern Art

Like many aspiring artists of his generation, Rusiñol saw Paris as the undisputed center of the art world. Around 1889, he made the pivotal move to the French capital, settling in the bohemian heart of Montmartre. This district, perched on a hill overlooking the city, was a melting pot of creativity, attracting painters, writers, musicians, and intellectuals from across Europe. Here, Rusiñol found not only inspiration but also camaraderie.

He shared lodgings and artistic adventures with fellow Catalan painter Ramon Casas i Carbó, forging a lifelong friendship and artistic dialogue. They were soon joined by other Spanish artists, including the Basque painter Ignacio Zuloaga and the versatile Catalan Miquel Utrillo, who would become a key figure in promoting Modernisme back in Barcelona. Living and working side-by-side, these artists absorbed the electric atmosphere of fin-de-siècle Paris. Rusiñol attended the Académie de la Palette, briefly studying under Henri Gervex, but his real education came from the city itself – its galleries, salons, cafés, and the intense debates about the future of art.

During his Parisian years, Rusiñol's style underwent a profound transformation. He moved away from the more anecdotal realism of his early work, embracing the innovations of French modern art. While Impressionism's focus on light and fleeting moments was an influence, Rusiñol gravitated more strongly towards Post-Impressionism and Symbolism. He admired the tonal harmonies and atmospheric mood of James McNeill Whistler and absorbed the subjective, often melancholic, and spiritually charged approach of Symbolist painters like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. This period saw him develop a more personal style, characterized by nuanced color palettes, evocative compositions, and a focus on mood over strict representation.

Return to Catalonia and the Rise of Modernisme

While Paris provided crucial artistic development, Rusiñol remained deeply connected to his Catalan roots. He traveled back and forth, bringing the latest artistic ideas from Paris to Barcelona. By the early 1890s, he became a leading figure in Catalan Modernisme. This movement, analogous to Art Nouveau and Jugendstil elsewhere in Europe, was more than an artistic style; it was a broad cultural phenomenon aiming to modernize Catalan society, assert its distinct identity, and integrate all forms of art and craft into a unified aesthetic vision.

Modernisme encompassed architecture, painting, sculpture, literature, music, and the decorative arts. Figures like the architects Antoni Gaudí and Lluís Domènech i Montaner were transforming Barcelona's cityscape, while writers like Joan Maragall were forging a new Catalan literary voice. Rusiñol, with his multifaceted talents and charismatic personality, was perfectly positioned to bridge the visual and literary arts within this movement. He championed the idea of "art for art's sake" and promoted a vision of the artist as a sensitive soul, often at odds with bourgeois materialism – a theme recurring in his paintings and writings.

His return was not just a geographical shift but an ideological one. He sought to synthesize his Parisian experiences with his Catalan identity, creating an art that was both modern and deeply personal, often finding inspiration in the landscapes, traditions, and moods of his homeland. He became a cultural animator, organizing events, contributing to journals, and fostering a sense of community among Modernista artists and writers.

Cau Ferrat: A Temple of Modernisme in Sitges

Rusiñol's commitment to Modernisme found its most tangible expression in Sitges, a picturesque coastal town south of Barcelona. Attracted by its light and atmosphere, Rusiñol acquired two fishermen's houses in 1893 and, with the help of his friend Miquel Utrillo and architect Francesc Rogent, transformed them into a unique home-studio he named Cau Ferrat ("Iron Den"). The name reflected his passion for collecting antique wrought iron, a craft he helped revive and appreciate as an art form.

Cau Ferrat quickly became much more than a private residence. It evolved into a sanctuary for Rusiñol's diverse collections, which grew to include paintings (notably two works by El Greco, acquired with Zuloaga in Paris), glass, ceramics, archaeological finds, and his own artworks. More importantly, it became the epicenter of Modernista cultural life outside Barcelona. Rusiñol organized the famous Festes Modernistes (Modernista Festivals) here between 1892 and 1899. These events were ambitious Gesamtkunstwerk experiments, combining theatre performances (often of Rusiñol's own plays or works by Symbolists like Maurice Maeterlinck), poetry readings, musical concerts (featuring composers like Enric Morera or Erik Satie, whom Rusiñol painted), and art exhibitions.

The Festes Modernistes were crucial in defining and disseminating the ideals of the movement. They attracted artists, writers, musicians, and critics, generating public debate and positioning Sitges, under Rusiñol's influence, as a vital cultural hub. Cau Ferrat itself, with its eclectic mix of art and craft, embodied the Modernista ideal of integrating art into life. Today, it functions as a public museum, preserving Rusiñol's legacy and offering a unique window into the era.

Els Quatre Gats: The Bohemian Heart of Barcelona

While Cau Ferrat was Rusiñol's coastal sanctuary, the café Els Quatre Gats (The Four Cats) served as the urban hub for Barcelona's bohemian and artistic avant-garde. Opened in 1897 in a striking Modernista building designed by Josep Puig i Cadafalch, the café was inspired by Parisian establishments like Le Chat Noir. Rusiñol, along with Ramon Casas, Miquel Utrillo, and Pere Romeu (the proprietor), were the driving forces behind it.

Els Quatre Gats was conceived as more than just a place to drink and socialize. It hosted art exhibitions, literary gatherings, puppet shows, and shadow plays, becoming the nerve center for Modernista activity in the city. Rusiñol was a regular presence, his wit and charisma contributing to the lively atmosphere. The café provided a crucial platform for young, emerging artists who struggled to find venues in the more conservative official salons.

It was here that a teenage Pablo Picasso had his first solo exhibition in 1900, facilitated by Casas and Rusiñol. Rusiñol recognized Picasso's burgeoning talent and offered encouragement. The vibrant intellectual and artistic exchange at Els Quatre Gats, fueled by figures like Rusiñol, Casas, Isidre Nonell, Joaquim Mir, Ricard Opisso, and many others, played a significant role in shaping the cultural landscape of Barcelona at the turn of the century and nurturing the next generation of artists, including the young Picasso.

The Painter: Landscapes, Gardens, and Symbolism

Painting remained the core of Rusiñol's artistic identity throughout his life. His style evolved from early realism through his Parisian engagement with Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, solidifying into a distinctive blend heavily influenced by Symbolism. He was less interested in capturing fleeting optical effects, like Claude Monet, and more focused on conveying mood, emotion, and a sense of timelessness or decay. His work often shares an affinity with the tonal harmonies and evocative atmospheres found in the paintings of James McNeill Whistler.

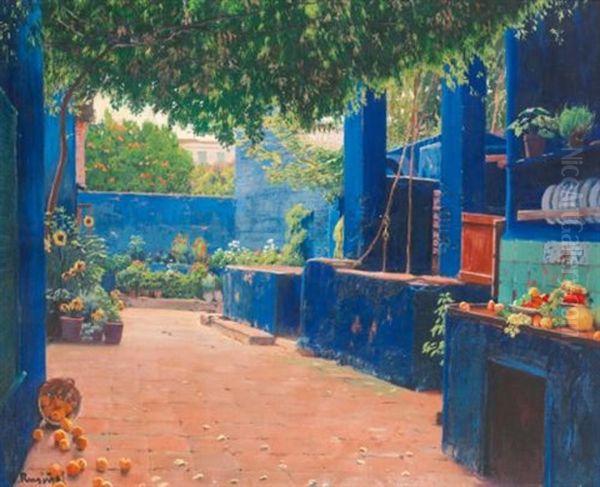

Gardens became Rusiñol's most characteristic and celebrated subject, particularly in his later career. He traveled extensively throughout Spain, seeking out historic gardens in Granada (the Alhambra and Generalife), Aranjuez, La Granja, Mallorca, and Valencia. These were not depicted as manicured, cheerful spaces but often as melancholic, abandoned, or overgrown realms, imbued with a sense of history, memory, and introspection. Cypress trees, stagnant fountains, crumbling statues, and shadowed pathways became recurring motifs, symbols of the passage of time, solitude, and the tension between nature and human artifice. His Jardins d'Espanya (Gardens of Spain) series, painted primarily between 1895 and 1915, represents the culmination of this thematic focus and is considered one of his major contributions to Spanish painting.

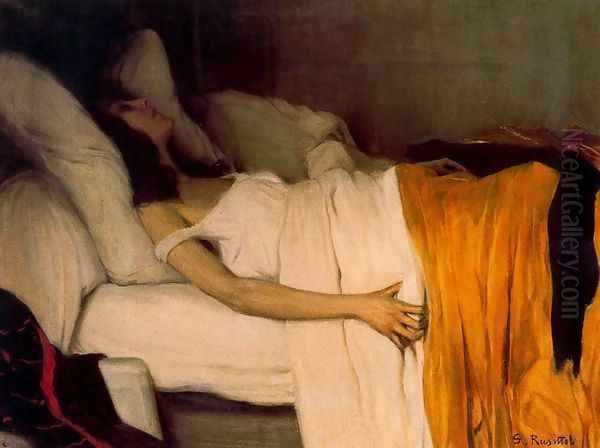

Beyond gardens, Rusiñol painted evocative landscapes, often featuring quiet corners of Catalonia or views from his travels. He also produced striking portraits, frequently depicting fellow artists (like his famous portrait of Erik Satie at the harmonium) or figures embodying a sense of Symbolist ennui or introspection. A notable and somewhat controversial work is La Morfina (The Morphine Addict, 1894), a sensitive portrayal of a woman succumbing to the drug, reflecting both Symbolist themes of decadence and perhaps Rusiñol's own later struggles with morphine, which he used for health reasons. His interiors, like Interior of a Café (c. 1892, Philadelphia Museum of Art), capture intimate moments with a focus on light and atmosphere.

The Writer: Poetry, Drama, and Prose

Rusiñol's creativity was not confined to the canvas; he was equally prolific and influential as a writer. He seamlessly integrated his literary and artistic pursuits, often exploring similar themes of beauty, melancholy, the artist's role in society, and the clash between idealism and materialism. His writing, like his painting, is deeply embedded in the Modernista and Symbolist ethos.

He achieved considerable success as a playwright. His plays often dramatized the conflict between the prosaic, conventional world of the bourgeoisie and the sensitive, artistic spirit. L'Alegria que Passa (The Joy That Passes By, 1898) is perhaps his most famous dramatic work, a lyrical piece about a traveling circus troupe bringing fleeting color and poetry to a dull, grey town. Other significant plays include El Jardí Abandonat (The Abandoned Garden, 1900), which directly echoes his painted garden themes, Cigales i Formigues (Cicadas and Ants, 1901), and La Bona Gent (The Good People, 1906). His plays were regularly performed and contributed significantly to the renewal of Catalan theatre.

Rusiñol was also a gifted poet and prose writer. He published collections of poetry and wrote numerous articles, essays, and travelogues for newspapers and journals, including the influential Barcelona daily La Vanguardia. His travel writings, often collected in books like Anant pel Món (Traveling the World) and Fulls de la Vida (Pages of Life), blended observation with personal reflection and artistic sensibility. He possessed a sharp wit and a talent for humorous and satirical prose, often gently mocking the pretensions of bourgeois society. His ability to excel in both visual and literary arts made him a uniquely central figure in the Modernista movement.

Collaborations and Contemporaries

Rusiñol's career was deeply intertwined with those of his contemporaries. His relationship with Ramon Casas was particularly significant – a close friendship marked by mutual respect, shared experiences (like their time in Paris and Montmartre, their involvement in Els Quatre Gats), and artistic collaboration (they sometimes exhibited together and even painted companion portraits of each other, such as the ones from Sant Benet de Bages in 1890). While friends, their artistic paths diverged somewhat: Casas became renowned for his elegant portraits of the Catalan elite and scenes of modern urban life, while Rusiñol pursued a more introspective, Symbolist path focused on landscapes and gardens.

His association with Miquel Utrillo was also crucial, particularly in the organization of the Festes Modernistes at Cau Ferrat and the running of Els Quatre Gats and its associated art journal, Pèl & Ploma. His friendship with Ignacio Zuloaga connected him to artists interested in Spanish tradition and led to the important acquisition of the El Greco paintings. His mentorship role for the young Pablo Picasso at Els Quatre Gats highlights his influence on the next generation.

Rusiñol moved within a wide circle of Modernista figures. He interacted with painters like the socially conscious Isidre Nonell, the vibrant colorist Joaquim Mir, and the internationally successful Hermen Anglada Camarasa. He shared the cultural stage with architects like Gaudí and Domènech i Montaner, whose work defined the visual identity of Modernista Barcelona, and writers like the poet Joan Maragall. His engagement with international figures like Whistler and Maeterlinck, and musicians like Satie and Morera, underscores the cosmopolitan nature of Catalan Modernisme, which Rusiñol himself embodied.

Travels, Inspirations, and Japonisme

Travel was a constant source of inspiration for Rusiñol. His time in Paris was formative, but his journeys within Spain were equally crucial, especially for his landscape and garden paintings. The discovery of the historic gardens of Aranjuez, near Madrid, and the Alhambra and Generalife in Granada provided him with enduring motifs. These locations, steeped in history and often tinged with a sense of romantic decay, perfectly suited his Symbolist temperament. He captured their unique atmospheres – the interplay of light and shadow, water and architecture, lush vegetation and weathered stone – with profound sensitivity. Mallorca also became a favorite location, its tranquil patios and landscapes appearing frequently in his later work.

Like many artists of his era, Rusiñol was fascinated by Japanese art and aesthetics, a phenomenon known as Japonisme. He was an early collector of Japanese prints and artifacts. While not always overtly present in his style, the influence of Japanese art can be discerned in certain compositional choices, the use of decorative patterns, and a focus on atmosphere and suggestion rather than literal depiction. This interest reflects his broader engagement with diverse artistic traditions and his search for new modes of expression beyond Western academic conventions.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

In his later years, Rusiñol continued to paint, primarily focusing on the garden themes that had become his signature. He remained a respected figure in the Catalan cultural scene, although the heyday of Modernisme had passed, giving way to Noucentisme, a movement emphasizing classical order and civic values. His health declined, and he relied on morphine for pain relief, an aspect of his life sometimes linked to the melancholic tone of his work and the subject of his earlier painting La Morfina.

He passed away in 1931 in Aranjuez, the site of one of the royal gardens he had painted so often and loved so dearly. His death marked the end of an era. Santiago Rusiñol left behind an immense and varied body of work encompassing painting, drawing, literature, and theatre. His influence on Catalan culture was profound and multifaceted. He was instrumental in shaping and promoting Modernisme, bridging Catalan art with broader European trends, particularly Symbolism.

His legacy is preserved most vividly in the Cau Ferrat Museum in Sitges, which houses a significant portion of his art collection, personal belongings, and works by his contemporaries, offering an unparalleled immersion into his world and the Modernista period. Numerous streets in Catalonia and Spain bear his name, a testament to his enduring fame. More importantly, his paintings, especially the hauntingly beautiful garden scenes, continue to be admired for their technical skill, poetic sensibility, and evocative power, securing his place as one of the most important Spanish artists of his generation.

Conclusion: The Total Artist of Modernisme

Santiago Rusiñol i Prats was more than a painter or a writer; he was a "total artist," embodying the Modernista ideal of integrating art into every facet of life. His journey from the heir of an industrial fortune to the bohemian leader of an artistic revolution encapsulates the cultural transformations of his time. Through his evocative paintings, poignant writings, and tireless cultural animation, he captured the spirit of Catalan Modernisme – its yearning for beauty, its embrace of symbolism and subjectivity, its dialogue between local identity and international currents, and its critique of bourgeois materialism. Rusiñol's unique blend of artistic talent, literary skill, and charismatic leadership made him the veritable soul of an era, leaving an indelible mark on the cultural heritage of Catalonia and Spain.