Sarah Miriam Peale stands as a pivotal figure in the narrative of American art, particularly as one of the nation's first professional female artists to achieve widespread recognition and financial independence through her craft. Born into a dynasty of painters, she carved out a distinct and respected career, primarily as a portraitist, but also as a skilled painter of still lifes. Her life and work offer a fascinating glimpse into the artistic, social, and cultural landscape of 19th-century America, highlighting both the opportunities and challenges faced by women aspiring to professional careers in the arts.

Early Life and Artistic Immersion in Philadelphia

Sarah Miriam Peale was born on May 19, 1800, in the vibrant city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. At the time, Philadelphia was not only the former capital of the fledgling United States but also its cultural and intellectual heart. This environment was particularly conducive to artistic pursuits, and Sarah was born into a family that was at the very center of this artistic ferment.

She was the youngest daughter of James Peale, himself a noted painter of miniatures and still lifes, and Mary Chambers Claypoole Peale. Her uncle was the even more renowned Charles Willson Peale, a polymath, naturalist, inventor, and one of the most influential figures in early American art. Charles Willson Peale founded one of the first museums in America, the Peale Museum in Philadelphia, and was a prolific portraitist of Revolutionary War heroes and leading figures of the new republic, including George Washington.

Growing up in such a household meant that art was not a distant concept but an everyday reality. The Peale family operated almost as an artistic guild, with skills and knowledge passed down through generations. Sarah and her sisters, Anna Claypoole Peale (also a distinguished miniaturist and still life painter) and Margaretta Angelica Peale (known for her still lifes), received their initial artistic training directly from their father. James Peale, though perhaps overshadowed by his brother Charles, was a meticulous craftsman and provided his daughters with a solid foundation in drawing and painting techniques.

Further enriching her education, Sarah also benefited from the guidance and influence of her uncle Charles Willson Peale and her cousins, particularly Rembrandt Peale and Raphaelle Peale, both of whom became significant artists in their own right. Rembrandt Peale achieved fame for his "Patriae Pater" portrait of George Washington and his grand historical canvases, while Raphaelle Peale is considered one of America's first professional still life painters, known for his deceptively simple yet masterfully executed compositions. This familial network of artists provided an unparalleled learning environment, offering encouragement, critique, and exposure to a variety of artistic approaches.

The Peale Dynasty: A Legacy of Art and Science

To fully appreciate Sarah Miriam Peale's journey, it's essential to understand the unique phenomenon of the Peale family. Charles Willson Peale, the patriarch of this artistic clan, believed deeply in the Enlightenment ideals of reason, education, and the pursuit of knowledge. He saw art not merely as a decorative pursuit but as a means of moral instruction, historical documentation, and scientific inquiry. He famously named his children after renowned artists and scientists – Raphaelle, Rembrandt, Rubens, Titian, Angelica Kauffman, and Sophonisba Angusciola, among others – embedding his aspirations for them from birth.

The Peale Museum in Philadelphia was a testament to this fusion of art and science, displaying portraits of eminent Americans alongside natural history specimens, including a complete mastodon skeleton that Charles Willson Peale himself excavated. This environment fostered a respect for accurate observation and meticulous rendering, qualities that became hallmarks of the Peale family style.

Sarah's father, James Peale, while also a portraitist, particularly excelled in miniature painting, a demanding genre requiring precision and a delicate touch. He also produced a significant body of still life paintings, often featuring arrangements of fruit and tableware, characterized by their rich colors and careful attention to texture. These familial influences, emphasizing both verisimilitude in portraiture and the detailed depiction of objects in still life, profoundly shaped Sarah's artistic development. The Peale women, including Sarah and Anna, were not merely dabblers but serious artists who contributed significantly to the family's artistic output and reputation.

Breaking Barriers: The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

A significant milestone in Sarah Miriam Peale's early career, and a testament to her burgeoning talent, occurred in 1824. In that year, she and her sister Anna Claypoole Peale were elected as Academicians by the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA). Founded in 1805 by Charles Willson Peale and sculptor William Rush, among others, PAFA was the first and oldest art museum and art school in the United States.

Their election was a landmark event. At a time when women were largely excluded from professional artistic societies and formal academic training, Sarah and Anna became the first women to receive this honor from PAFA. This recognition not only validated their artistic abilities but also signaled a slow but perceptible shift in the art world's attitudes towards female artists. It placed them on par, at least in title, with established male artists of the day, such as Thomas Sully, a leading portrait painter in Philadelphia, and Jacob Eichholtz.

Sarah began exhibiting her work at PAFA as early as 1817, initially showing still lifes. Her first exhibited portrait appeared in 1818. Her consistent participation in these annual exhibitions helped to build her reputation and attract patrons. The critical acclaim she received for her detailed and lifelike portrayals, as well as her vibrant still lifes, set her apart.

Artistic Style: Realism, Detail, and Psychological Insight

Sarah Miriam Peale's artistic style is firmly rooted in the American tradition of realism, heavily influenced by the Peale family's emphasis on accurate representation. Her portraits are characterized by their clarity, meticulous attention to detail, and a direct, often unidealized, depiction of the sitter. She possessed a remarkable ability to capture a strong likeness, paying close attention to the individual features, skin tones, and hair textures of her subjects.

A distinctive feature of her portraiture is the exquisite rendering of costume and accessories. Lace, silk, velvet, jewelry, and other elements of attire are depicted with a precision that speaks to her keen observational skills and technical mastery. This was not merely for decorative effect; these details often conveyed the social status and personality of the sitter, adding another layer of meaning to the portrait. Her brushwork was generally smooth and controlled, contributing to the polished finish of her canvases.

While her style shared commonalities with other Peale family members, particularly in its commitment to verisimilitude, Sarah developed her own distinct voice. Her portraits often convey a sense of the sitter's presence and personality, suggesting a psychological engagement that goes beyond a mere surface likeness. She managed to imbue her subjects with a sense of dignity and individuality.

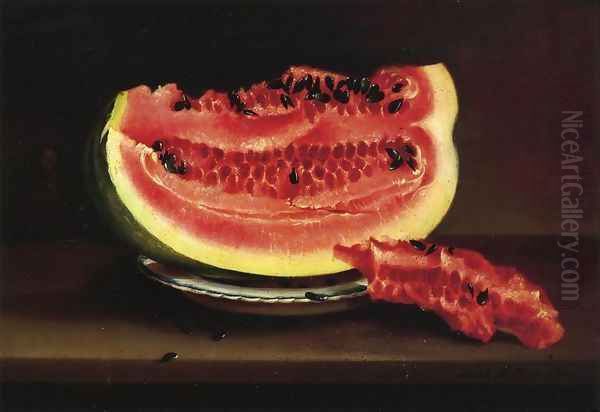

In her still life paintings, Sarah also excelled. These works, typically featuring arrangements of fruit or flowers, are characterized by their vibrant colors, rich textures, and balanced compositions. Works like Still Life with Fruit in a China Bowl and Still Life with Watermelon showcase her ability to render the varied textures of fruit, the gleam of porcelain, and the play of light with remarkable skill. These still lifes, while perhaps less numerous than her portraits, demonstrate her versatility and her mastery of this genre, which was also a Peale family specialty, with Raphaelle Peale being a preeminent practitioner.

A Flourishing Career in Baltimore

In 1825, seeking greater professional opportunities and perhaps a chance to establish her own artistic identity away from the dense concentration of Peale artists in Philadelphia, Sarah Miriam Peale moved to Baltimore, Maryland. This move proved to be highly successful. Baltimore was a prosperous port city with a growing class of wealthy merchants, politicians, and professionals eager to have their likenesses captured for posterity.

For over two decades, from 1825 to 1847, Sarah Peale was the most sought-after and prolific portrait painter in Baltimore. She established a studio and received a steady stream of commissions, producing over one hundred portraits during her time in the city. Her sitters included prominent figures such as politicians, military officers, clergymen, and members of Baltimore's social elite.

Among her notable commissions was a portrait of the Marquis de Lafayette, the French hero of the American Revolution, during his celebrated return tour of the United States in 1824-1825. Painting such a distinguished international figure would have significantly enhanced her reputation. She also painted other influential individuals, including Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, a powerful political figure of the Jacksonian era.

Her success in Baltimore was remarkable for any artist, but particularly for a woman in the 19th century. She managed her own studio, negotiated commissions, and supported herself entirely through her art, a level of professional independence achieved by very few women of her time. Her ability to consistently attract high-profile clients speaks volumes about the quality of her work and her professionalism. Artists like John Wesley Jarvis and Chester Harding were also active portraitists during this period, providing a competitive landscape in which Peale thrived.

Washington D.C. and St. Louis: Continued Success

While based in Baltimore, Sarah Peale also made frequent trips to Washington D.C. to undertake portrait commissions. The capital city, with its concentration of politicians, diplomats, and government officials, provided another important market for her talents. Her ability to secure commissions in these competitive urban centers underscores her established reputation.

In 1847, after more than twenty successful years in Baltimore, Sarah Miriam Peale moved to St. Louis, Missouri, possibly to be near family members who had relocated there. St. Louis, at the time, was a rapidly growing city, a gateway to the West, and offered new opportunities for a portrait painter of her caliber. She continued her prolific career in St. Louis for another three decades, remaining an active and respected artist.

Even in St. Louis, she maintained her high standards and continued to produce portraits that were praised for their likeness and technical skill. Her style, while consistent in its realism, may have subtly evolved over the years, but her commitment to capturing the character of her sitters remained paramount. She adapted to the changing tastes and clientele of a new city, demonstrating her resilience and enduring appeal as an artist. The artistic environment in St. Louis would have been different from the more established centers of Philadelphia and Baltimore, perhaps with artists like George Caleb Bingham, known for his genre scenes of frontier life, representing a different facet of American art.

Notable Works: Capturing an Era

Several of Sarah Miriam Peale's works stand out as particularly representative of her skill and artistic vision.

Her Portrait of Mrs. William Crane (often referred to as Portrait of Lady) is a fine example of her mature style. The painting depicts a confident and self-possessed woman, rendered with Peale's characteristic attention to detail in the lace collar, the intricate hairstyle, and the subtle modeling of the face. The work conveys a sense of the sitter's intelligence and strength, reflecting the emerging ideal of the "Republican Mother" and the growing self-awareness of women in 19th-century America.

The portrait of Mary Leypold Griffith (Mrs. Robert Eglesfeld Griffith) and Her Son Robert Eglesfeld Griffith Jr., painted around 1839-1840, is another significant work. It showcases her ability to handle complex compositions involving multiple figures and to capture familial relationships. The depiction of the textures of clothing and the tender interaction between mother and child are masterfully executed. A related group portrait of the Griffith Family, painted in 1841, is particularly noteworthy for its social commentary, as it reportedly included an enslaved servant, offering a rare glimpse into the complexities of household dynamics and race relations in the antebellum South, a subject rarely broached so directly in formal portraiture of the era.

Her portraits of men, such as Senator Thomas Hart Benton, often convey a sense of authority and intellectual gravitas, fitting for public figures. She did not shy away from depicting the signs of age or character in her sitters' faces, preferring an honest portrayal to a flattering but less truthful one. This integrity was likely appreciated by her clients, who sought a lasting and accurate record of their appearance.

Her still lifes, like A Slice of Watermelon (circa 1825), demonstrate a different facet of her talent. These works are often intimate in scale but rich in color and texture. The glistening, juicy flesh of the watermelon, the dark seeds, and the rough green rind are rendered with a palpable realism that engages the senses. These paintings connect her to the broader Peale family tradition of still life painting, pioneered by James Peale and Raphaelle Peale, and continued by other family members like Margaretta Angelica Peale.

Personal Life and Dedication to Art

Sarah Miriam Peale never married and, by all accounts, dedicated her life almost entirely to her art. This was an unusual choice for a woman in the 19th century, when societal expectations typically steered women towards marriage and domestic roles. Her decision to remain single allowed her the freedom and focus necessary to pursue a demanding professional career. She was, in essence, a career woman in an era when that concept was virtually non-existent for women, especially in a field as competitive as art.

Her dedication paid off, as she achieved a level of financial success and professional recognition that was rare for female artists of her generation. She managed her finances, ran her own studio, and navigated the art market with considerable acumen. Her life serves as an inspiring example of a woman who successfully forged an independent path in the professional world. Other female artists, such as Lilly Martin Spencer, who came to prominence slightly later, also juggled artistic careers with family life, but Peale's single-minded devotion to her profession was distinctive.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Sarah Miriam Peale continued to paint actively in St. Louis until late in her life. Her output gradually decreased in her final years, but she remained a respected figure in the city's artistic community. She passed away in St. Louis on February 4, 1885, at the age of 84, leaving behind a substantial body of work that documents prominent citizens and reflects the artistic tastes of her time.

Her legacy is multifaceted. As an artist, she was a highly skilled portraitist and still life painter who upheld the Peale family tradition of realism and meticulous craftsmanship. Her portraits provide invaluable historical records of the individuals who shaped American society in the 19th century.

Perhaps more significantly, Sarah Miriam Peale was a trailblazer for women in the arts. Her professional success and her election to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts helped to open doors for subsequent generations of female artists. She demonstrated that women could not only create art of high quality but also achieve professional standing and financial independence through their artistic endeavors. While she may not have been an overt feminist in the modern sense, her life and career were a powerful statement of female capability and ambition.

Her work influenced and inspired others, including later female artists like Mary Cassatt, who, though part of a different artistic movement (Impressionism) and a later generation, would have recognized the pioneering efforts of women like Sarah Peale in establishing a place for female artists in the American art world. The tradition of strong female portraitists continued with artists like Cecilia Beaux later in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Today, Sarah Miriam Peale's paintings are held in the collections of major American museums, including the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C., the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the Baltimore Museum of Art, and the Saint Louis Art Museum. Her work continues to be studied and appreciated for its artistic merit, its historical significance, and for what it tells us about the life of a remarkable woman who defied conventions to become one of America's foremost early professional artists. Her contributions ensure her a lasting place in the annals of American art history, not just as a member of the illustrious Peale family, but as a significant artist in her own right.