The Dutch Golden Age, spanning roughly the 17th century, was a period of extraordinary artistic efflorescence in the Netherlands. Amidst a galaxy of male masters, a few exceptionally talented women managed to carve out significant careers. Among these, Judith Leyster stands as a particularly compelling figure, a painter of remarkable skill and vivacity whose work, after centuries of neglect, has been rightfully restored to its prominent place in art history. Her story is one of talent, ambition, professional recognition, and the unfortunate, yet common, fate of many female artists whose legacies were obscured by time and societal biases.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Haarlem

Judith Jansdr Leyster was baptized in Haarlem on July 28, 1609. She was the eighth child of Jan Willemsz Leyster, a brewer and cloth maker. Her father's brewery was called "De Leystar," meaning "lodestar" or "pole star," and Judith would later adopt a distinctive monogram incorporating her initials "JL" with a star, a clever play on her family name. While concrete details about her earliest training are scarce, the quality of her mature work suggests a thorough and professional apprenticeship.

Haarlem, during Leyster's youth, was a vibrant artistic center, second only to Amsterdam. It was home to influential painters like Frans Hals, known for his lively and spontaneous portraiture, and a burgeoning school of landscape and genre painters. It is highly probable that Leyster received her initial instruction from Frans Pietersz. de Grebber, a respected Haarlem painter known for portraits and historical subjects, who also ran a significant workshop. Some scholars also speculate that she may have spent some time in Utrecht, where she could have been exposed to the dramatic chiaroscuro and earthy realism of the Utrecht Caravaggisti, such as Hendrick ter Brugghen and Gerrit van Honthorst, whose influence is discernible in some of her early works.

The possibility of a direct apprenticeship or association with Frans Hals has been a subject of much discussion. Her dynamic brushwork, informal compositions, and focus on capturing fleeting expressions certainly bear a resemblance to Hals's style. Indeed, for many years after her death, several of Leyster's paintings were mistakenly attributed to Hals. While no definitive documentary proof of a formal apprenticeship under Hals exists, the stylistic affinities are undeniable, suggesting at the very least a strong influence or a period of working in close proximity to his circle. Samuel Ampzing, in his 1628 book "Beschrijvinge ende lof der stadt Haerlem in Holland" (Description and Praise of the Town Haarlem in Holland), mentions a "Judith Leystar" as one of the notable painters active in the city at the time, indicating she had already achieved some recognition by the age of nineteen.

Entry into the Guild and Professional Independence

A pivotal moment in Leyster's career came in 1633 when, at the age of 24, she was admitted as an independent master to the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke. This was a significant achievement for any artist, but particularly for a woman in the 17th century. Membership in the guild was essential for legally selling paintings, taking on pupils, and operating an independent workshop. Leyster was one of only two women recorded as members of the Haarlem guild during this period, the other being the still-life painter Maria de Grebber, daughter of Frans Pietersz. de Grebber.

Upon becoming a master, Leyster established her own studio and is known to have had at least three male apprentices. This fact is documented through a dispute she had with Frans Hals in 1635. One of her apprentices, Willem Woutersz, left her workshop after only a few days to join Hals's studio. Leyster took Hals to the Guild to recover damages, and the Guild ruled in her favor, albeit with a compromise, demonstrating her standing and willingness to assert her professional rights. This incident underscores her independent status and business acumen.

Her workshop would have been a busy place, producing paintings for the open market as well as commissioned pieces. The Dutch art market was unique in its breadth, with a growing middle class eager to adorn their homes with art, creating demand for portraits, genre scenes, landscapes, and still lifes. Leyster adeptly catered to these tastes.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Judith Leyster's oeuvre, though relatively small with around twenty surviving authenticated works, showcases a remarkable versatility and a distinctive artistic voice. She primarily focused on genre scenes, portraits, and a few still lifes. Her style is characterized by its vivacity, informal and often asymmetrical compositions, and a keen observation of human character and everyday life.

Her genre paintings often depict scenes of merry-making, music, and domestic life, themes popular among her contemporaries like Adriaen Brouwer, Adriaen van Ostade, and her future husband, Jan Miense Molenaer. However, Leyster brought a unique energy and often a subtle psychological depth to these subjects. Her figures are animated, their gestures and expressions captured with a seemingly effortless spontaneity. She had a particular fondness for depicting children, capturing their playful antics with charm and empathy.

A hallmark of Leyster's technique is her relatively loose and free brushwork, which imbues her paintings with a sense of immediacy and dynamism. This is particularly evident in the rendering of fabrics, hair, and fleeting facial expressions. While this approach shares similarities with Frans Hals, Leyster's touch is often more delicate, and her palette can be more varied and nuanced. She demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of light and shadow, using chiaroscuro not just for dramatic effect but also to model form and create atmosphere. Her figures often emerge from dimly lit backgrounds, illuminated by a focused light source that highlights their features and actions.

In her portraits, Leyster aimed to capture the personality of her sitters rather than merely their likeness. Her Self-Portrait (c. 1630, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.) is a prime example of her skill in this genre and a bold statement of her artistic identity.

Key Masterpieces: A Closer Look

Self-Portrait (c. 1630): This iconic work is arguably Leyster's most famous. It depicts her seated before an easel, palette and brushes in hand, turning to smile engagingly at the viewer. On the easel is a painting of a fiddler, a common motif in her genre scenes. The portrait is remarkable for its informality and confidence. Leyster presents herself not in the stiff, formal attire typical of many portraits of the era, but in fashionable, elegant clothing, including a large lace collar and cuffs, suggesting her success and status. The painting is a powerful assertion of her identity as a professional artist, actively engaged in her craft, yet relaxed and approachable. The dynamic pose and lively brushwork are characteristic of her style.

The Proposition (c. 1631): Housed in the Mauritshuis, The Hague, this painting is a fascinating example of Leyster's ability to infuse a common genre theme with a unique perspective. It depicts a woman engrossed in her sewing by candlelight, while a man leans over her, offering her a handful of coins, presumably as an inducement for sexual favors. Unlike many contemporary depictions of such scenes, which often carried a moralizing or titillating tone, Leyster focuses on the woman's quiet dignity and apparent disinterest in the man's offer. The woman remains focused on her needlework, her face illuminated and composed, while the man's face is partly in shadow, his gesture intrusive. This subtle psychological drama and the sympathetic portrayal of the woman distinguish Leyster's approach. The use of candlelight allows for a masterful play of light and shadow, enhancing the intimacy and tension of the scene.

The Concert (c. 1631-1633): This lively genre scene, now in a private collection, showcases Leyster's skill in depicting musical gatherings. It features three musicians: a woman playing a lute, a man playing a violin, and another man singing from a songbook. The figures are closely grouped, creating a sense of camaraderie and shared enjoyment. The expressions are animated, and the rendering of the instruments and costumes is detailed and convincing. The composition is dynamic, with diagonal lines created by the instruments and the gazes of the figures. It has been suggested that the figures might be portraits, possibly including Leyster herself and her future husband, Jan Miense Molenaer, though this remains speculative. The painting exemplifies the Dutch love for music and convivial social scenes.

Merry Company (c. 1630): This painting, also known as The Carousing Couple, is another vibrant example of her genre work. It depicts a man and a woman, possibly a self-portrait with Molenaer, enjoying wine and music. The figures are rendered with Leyster's characteristic loose brushwork and animated expressions. The scene is filled with a sense of joviality and exuberance. Such paintings catered to the taste for scenes of everyday pleasure and were popular in the Dutch market.

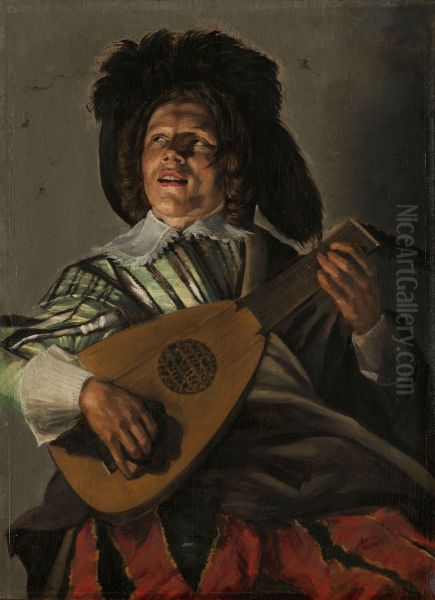

The Jester (c. 1625) or The Lute Player: This work, often compared to similar figures by Frans Hals (like his Lute Player), shows a musician in theatrical costume, joyfully playing his instrument. The figure's direct gaze and expressive face engage the viewer. Leyster's ability to capture a sense of movement and sound is evident here. The vibrant colors and energetic brushwork contribute to the painting's lively atmosphere.

Her still lifes, though fewer in number, such as Still Life with a Basket of Fruit (c. 1635-1640), demonstrate her skill in rendering textures and her understanding of composition, aligning her with other still life specialists of the period like Pieter Claesz or Willem Claeszoon Heda, though her approach was generally less formal than theirs.

Marriage to Jan Miense Molenaer and Later Career

In 1636, Judith Leyster married Jan Miense Molenaer, also a prolific and successful genre painter. Molenaer's work often depicted similar themes of peasant life, taverns, and domestic scenes, though his style was generally broader and more overtly comical than Leyster's. After their marriage, the couple moved from Haarlem to Amsterdam, a larger and more competitive art market. They later resided in Heemstede, near Haarlem, where they had a country estate.

It is a notable and often lamented fact that Leyster's artistic production appears to have significantly declined after her marriage. While she may have collaborated with her husband on some paintings or assisted in his workshop, very few works are securely attributed to her from this later period. The reasons for this decline are likely complex. The demands of raising a family (they had five children, though only two survived to adulthood), managing a household, and possibly assisting with her husband's business affairs may have left her with little time or energy for her own painting. This was a common pattern for female artists of the era who married.

Despite the reduced output, it's not accurate to say she abandoned art entirely. There is evidence she was involved in her husband's art dealing activities. However, the vibrant, independent artistic career she had established in Haarlem in the early 1630s did not continue with the same intensity after her marriage. She died in Heemstede in 1660 and was buried on February 10. At the time of her death, her artistic reputation, though perhaps diminished from its peak, was still acknowledged.

The Period of Obscurity and Misattribution

Following her death, Judith Leyster's name and work gradually faded into obscurity. This was, unfortunately, a common fate for many female artists before the 20th century. Within a couple of generations, her distinct artistic identity was largely forgotten. Many of her paintings, due to their stylistic similarities in energy and subject matter, were reattributed to Frans Hals. Others were ascribed to her husband, Jan Miense Molenaer, or simply listed as anonymous.

The signature she used, a monogram "JL" with the star, was either overlooked, misinterpreted, or in some cases, even painted over and replaced with a forged Frans Hals signature to increase a painting's market value. For nearly two centuries, one of the most talented painters of the Dutch Golden Age was effectively erased from art historical narratives. Artists like Dirck Hals (Frans's brother), also a genre painter, maintained their identities, but Leyster's was subsumed.

Rediscovery and Reassessment in the Late 19th Century

The "rediscovery" of Judith Leyster began in the late 19th century, a period that saw a burgeoning interest in art history and the systematic cataloging of Dutch Golden Age painting. The pivotal moment came in 1893. The Louvre in Paris had acquired a painting titled The Happy Couple (also known as Carousing Couple or Jolly Companions), believing it to be by Frans Hals. However, upon closer examination, the art historian Cornelis Hofstede de Groot, a leading scholar of Dutch art, identified Leyster's distinctive monogram.

This discovery sparked a wave of research. Scholars began to re-examine other paintings attributed to Hals and Molenaer, searching for Leyster's signature or stylistic characteristics. Gradually, a body of work was reattributed to her, and her artistic personality began to re-emerge. Hofstede de Groot's 1893 article, "Judith Leyster: A Dutch Precursor of Chardin," was instrumental in bringing her to public attention. Other scholars, like Juliane Harms in the 1920s and 1930s, continued the work of reconstructing her oeuvre and biography.

The rediscovery was not without its challenges. Distinguishing her hand from that of Hals or Molenaer, especially in unsigned works or those where collaboration might have occurred, remains a complex task for connoisseurs. However, the core group of signed and stylistically consistent works firmly established her as an artist of significant talent and originality.

Unresolved Questions and Ongoing Debates

Despite the progress made in understanding Judith Leyster's life and work, several questions and debates persist among art historians:

1. The Extent of Frans Hals's Influence: While the stylistic similarities are clear, the precise nature of their relationship – whether she was a formal pupil, an independent follower, or a friendly competitor – is still debated. Some scholars argue for a more independent development, while others emphasize Hals's formative impact.

2. The Decline in Production After Marriage: The reasons for her reduced output after 1636 continue to be discussed. Was it solely due to domestic responsibilities, a conscious choice, or were there other factors, such as the changing art market or a shift in her artistic interests?

3. Collaboration with Molenaer: The extent to which she collaborated with her husband is unclear. While it's likely they shared studio props and models, and may have occasionally worked on paintings together, identifying her specific contributions to Molenaer's workshop output is difficult. Some scholars have proposed that certain figures or passages in Molenaer's paintings might be by Leyster's hand.

4. The Full Scope of Her Oeuvre: While around 20-30 paintings are now confidently attributed to her, it is possible that more of her works remain misattributed or undiscovered. The search for "lost" Leysters continues.

5. Her Death: The exact cause of her death in 1660 at the relatively young age of 50 is not recorded. Speculation about illness, such as the plague which was recurrent, exists but lacks firm evidence.

Legacy and Enduring Significance

Judith Leyster's rediscovery has been a crucial moment in the broader effort to recover the histories of women artists. Her work is now celebrated in major museums worldwide, and she is recognized as one of the leading painters of the Dutch Golden Age. Her significance lies in several areas:

Pioneering Female Artist: She was one of the few women of her time to achieve professional recognition as a master painter, operate her own studio, and take on apprentices. Her success challenged the gender norms of the 17th-century art world.

Technical Skill and Artistic Innovation: Leyster was a highly skilled painter with a distinctive style characterized by lively brushwork, dynamic compositions, and insightful portrayals of everyday life. She brought a fresh perspective to genre painting, often imbuing her scenes with a subtle psychological depth and a focus on the female experience, as seen in The Proposition.

Influence and Contribution to Dutch Art: While her direct influence was curtailed by her period of obscurity, her work stands as an important contribution to the richness and diversity of Dutch Golden Age painting. She was part of a vibrant artistic community in Haarlem that included figures like Frans Hals, Adriaen Brouwer, Adriaen van Ostade, and later, landscape painters such as Jacob van Ruisdael and still-life masters like Willem Claeszoon Heda and Pieter Claesz. Her interactions with contemporaries like her husband Jan Miense Molenaer, and possibly earlier figures like Kees van Cleve or Willem Fabritius, enriched the artistic milieu.

Inspiration for Future Generations: Her story of talent, recognition, neglect, and rediscovery serves as an inspiration and a cautionary tale. It highlights the importance of ongoing research to ensure that the contributions of all artists, regardless of gender, are acknowledged and celebrated.

Judith Leyster's paintings continue to captivate viewers with their energy, charm, and technical brilliance. Her Self-Portrait remains a powerful emblem of female artistic ambition and achievement. As art history continues to evolve and become more inclusive, Judith Leyster's star, once obscured, now shines brightly, rightfully acknowledged as a luminous talent of her era. Her journey from a celebrated master in her own time, through centuries of anonymity, to her current esteemed position is a testament to the enduring power of her art.