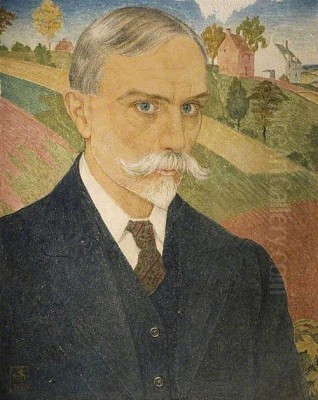

Joseph Edward Southall stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century British art. An artist of profound conviction, both in his meticulous technique and his deeply held pacifist and socialist beliefs, Southall was a leading light in the revival of tempera painting and a central member of the Birmingham Group of Artist-Craftsmen. His work, characterized by its luminous colour, precise linearity, and often allegorical or narrative content, forms a unique bridge between the ideals of the Pre-Raphaelites, the ethos of the Arts and Crafts movement, and the burgeoning, yet often contrasting, currents of early modernism.

Early Life and Quaker Foundations

Born in Nottingham on August 23, 1861, Joseph Edward Southall's upbringing within a devout Quaker family profoundly shaped his worldview and, consequently, his artistic and social engagements. His father, a merchant, passed away when Joseph was still an infant, and his mother also died relatively young. This early exposure to loss may have contributed to the reflective and sometimes melancholic undertones found in his later work. He received his education at Quaker institutions, including Ackworth School and Bootham School in York, environments that would have reinforced the Quaker testimonies of simplicity, peace, equality, and integrity.

After his schooling, Southall's family relocated to Birmingham, a city that was then a vibrant hub of industrial innovation but also a centre for artistic and social reform. It was here that his artistic inclinations began to take formal shape. He initially trained as an architect with the firm of Martin & Chamberlain, a leading practice in Birmingham known for its civic and educational buildings. However, his passion for painting soon led him to enroll at the Birmingham School of Art. This institution, under the influential directorship of Edward R. Taylor, was a crucible for the Arts and Crafts philosophy, heavily influenced by the teachings of John Ruskin and William Morris, emphasizing the unity of art and craft, the importance of skilled workmanship, and the social value of art.

The Italian Pilgrimage and the Rediscovery of Tempera

A pivotal moment in Southall's artistic development came with his first visit to Italy in 1883. This journey was not merely a Grand Tour in the traditional sense but a profound artistic pilgrimage. He was captivated by the brilliance and clarity of early Italian Renaissance frescoes and panel paintings, particularly the works of masters such as Fra Angelico, Benozzo Gozzoli, Sandro Botticelli, and Andrea Mantegna. He observed that these works, many executed in tempera, possessed a luminosity and permanence that seemed to elude contemporary oil painting techniques.

Tempera, an ancient medium where pigments are mixed with a water-soluble binder, typically egg yolk, had largely fallen out of favour with the rise of oil painting during the Renaissance. Southall, however, saw in its meticulous, layered application and its capacity for sharp detail and vibrant, jewel-like colour, a medium perfectly suited to his artistic temperament and the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement. He meticulously studied Cennino Cennini's 15th-century treatise, "Il Libro dell'Arte" (The Craftsman's Handbook), which provided detailed instructions on the preparation of panels and the techniques of tempera painting. This dedication to reviving an almost lost art form set him apart from many of his contemporaries. His commitment was not just to the aesthetic qualities of tempera but also to its craft-based, methodical approach, which resonated with Ruskinian ideals of honest labour and material integrity.

The Birmingham Group and the Arts and Crafts Ethos

Upon his return to Birmingham, Southall became a key figure in what became known as the Birmingham Group of Artist-Craftsmen. This informal association of artists, many of whom were also connected with the Birmingham School of Art, shared a common aesthetic rooted in the later phase of Pre-Raphaelitism, particularly the influence of Edward Burne-Jones (who himself had strong ties to Birmingham), and the principles of the Arts and Crafts movement. Other prominent members and associates included Arthur Gaskin, Charles March Gere, Henry Payne, and Sidney Meteyard.

The group emphasized fine craftsmanship, decorative qualities, and often drew inspiration from medieval romance, biblical narratives, and classical mythology, imbuing their subjects with a distinct, often dreamlike, symbolism. Southall, with his mastery of tempera, became a leading exponent of their ideals. He not only painted easel pictures but also engaged in a wide range of decorative work, including murals, furniture decoration, book illustration, and designs for stained glass and embroidery, truly embodying the Arts and Crafts ideal of the artist-craftsman. His home, often decorated and furnished with pieces of his own design or by his associates, became a testament to these principles.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Southall's artistic style is immediately recognizable. His use of tempera allowed for a clarity of line and a brilliance of colour that is distinct from the impasto and sfumato often associated with oil painting. His compositions are carefully structured, often with a strong sense of pattern and design. Figures are rendered with a delicate precision, their forms clearly delineated, and their expressions often conveying a quiet intensity or introspection. Landscapes and architectural settings are depicted with meticulous detail, contributing to the overall narrative and symbolic richness of his works.

His subject matter was diverse. He painted portraits, often of family and friends, imbued with a gentle intimacy. Mythological and biblical scenes allowed him to explore universal themes of love, loss, faith, and morality. He also depicted scenes from contemporary life, but often filtered through a romantic or idealized lens, sometimes with a subtle social commentary. His Quaker faith and pacifist convictions also found expression in his art, particularly in works created during times of conflict. He sought a beauty that was not merely superficial but one that conveyed truth and moral seriousness, aligning with Ruskin's belief in the ethical dimension of art.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several of Southall's works stand out as exemplars of his style and thematic preoccupations.

"The Agate" (1911), a self-portrait with his wife, Anna Elizabeth Baker (whom he married in 1903), is a tender and beautifully executed work. It depicts the couple on a beach, perhaps during one of their holidays in Southwold, Suffolk, a favourite location. The clarity of the light, the meticulous rendering of the figures and the coastal landscape, and the serene atmosphere are characteristic of his best tempera work. The title refers to the agate stone, perhaps symbolizing clarity, strength, or a precious find, reflecting the nature of their companionship.

"Gismonda, or Sigismonda Drinking the Poison" (1896-1897) is a powerful narrative painting based on a story from Boccaccio's "Decameron." It showcases Southall's ability to convey dramatic intensity through restrained gesture and symbolic detail. The rich colours, the careful composition, and the tragic beauty of the protagonist are hallmarks of his engagement with literary and historical themes, echoing Pre-Raphaelite interests.

"Ariadne in Naxos" (1925-1926) tackles a classical myth, depicting Ariadne abandoned by Theseus on the island of Naxos. Southall captures her desolation but also hints at her eventual rescue and deification by Dionysus. The painting demonstrates his continued mastery of tempera in his later career, with its luminous palette and refined drawing.

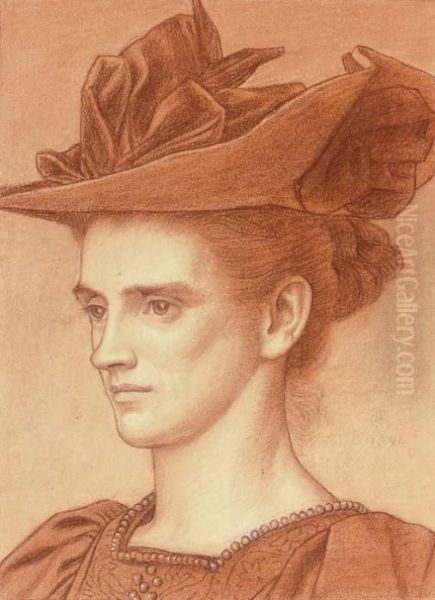

"The Daughter of Herodias" (circa 1897, the work auctioned in 1997 for a significant sum) is another example of his engagement with biblical narratives, likely depicting Salome. Such subjects allowed for rich costume, dramatic potential, and moral contemplation, themes popular with late Victorian and Edwardian artists like John William Waterhouse or Herbert Draper, though Southall's treatment would have been distinct in its tempera technique and perhaps more restrained emotional tenor.

His work "The Coral Necklace" (1894-1895) and the design "Exhibition Visit: Postcard Design" (1891) further illustrate his range, from intimate genre scenes to decorative designs, all executed with his characteristic precision.

The Society of Painters in Tempera

Recognizing the need for a platform to promote and share knowledge about the revived medium, Southall was instrumental in the formation of the Society of Painters in Tempera in 1901. He co-founded the society with other enthusiasts of the medium, notably John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, an older artist who had links to the Pre-Raphaelites and had long worked in tempera, and Lady Christiana Herringham, a painter and a crucial translator of Cennino Cennini's treatise.

The Society held regular exhibitions, published papers on the technique, and served as a focal point for artists interested in exploring alternatives to oil painting. Its membership included artists like Maxwell Armfield, who became a notable tempera painter himself and was a student and friend of Southall, and Walter Crane, a leading figure in the Arts and Crafts movement. The Society played a vital role in ensuring that tempera painting gained a renewed respect and understanding within the British art world and beyond, influencing subsequent generations of artists who sought its unique qualities. Southall's dedication to the society and its aims was unwavering, and he exhibited frequently with them.

Pacifism, Socialism, and Political Engagement

Southall's Quaker faith was not a passive belief system but an active force that guided his engagement with the world. He was a committed pacifist and a socialist, beliefs that were often intertwined with the Arts and Crafts movement's critique of industrial capitalism and its social inequalities, as articulated by figures like William Morris.

His pacifism became particularly prominent during times of war. He was a vocal opponent of the Boer War and later, the First World War. During WWI, his convictions led him to create powerful anti-war art. He produced a series of cartoons and illustrations for pacifist publications, often starkly critical of militarism and the glorification of war. One of his most significant works in this vein was "The Ghosts of the Slain" (1915), a series of illustrations for a pamphlet written by R.L. Outhwaite, which depicted the horrors of war and condemned those who profited from it. These works, often executed in a bold, graphic style, were a departure from his more idyllic easel paintings but demonstrated the depth of his moral commitment.

He was also actively involved in political life, supporting the Independent Labour Party and advocating for social justice. He opposed the Jameson Raid of 1895, an ill-fated attempt to overthrow the Transvaal Republic, and was a supporter of the Liberal Party at various times. His political activism was a natural extension of his artistic and ethical principles, believing that art had a role to play in creating a more just and peaceful society. This stance sometimes put him at odds with mainstream opinion, but he remained steadfast in his beliefs.

Wider Artistic Connections and Influence

Beyond the Birmingham Group and the Society of Painters in Tempera, Southall's work was exhibited more widely, including at the Royal Academy, the New English Art Club, and internationally. A significant exhibition of his work at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris in 1910 brought him considerable acclaim in France, where critics praised his technical skill and the unique beauty of his tempera paintings. This international recognition was a testament to the distinctiveness of his vision.

His influence extended to his students and younger contemporaries. Maxwell Armfield, as mentioned, became a prominent tempera painter under his guidance. The clarity and precision of Southall's style, as well as his commitment to craftsmanship, offered an alternative path for artists who were not drawn to the emerging avant-garde movements like Cubism or Fauvism, yet sought a modern expression rooted in tradition. While he might be considered one of the "last Romantics," his work was not merely nostalgic. It was a conscious effort to forge a contemporary art form based on enduring principles of beauty, skill, and meaning. He admired the work of contemporary French Post-Impressionists like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes for their mural-like qualities and simplified forms, which shared some affinities with his own aims for clarity and decorative harmony.

He also maintained connections with other artists who shared an interest in reviving older techniques or who were part of the broader Arts and Crafts sphere, such as the stained-glass artist Christopher Whall or the calligrapher Edward Johnston, whose revival of lettering arts paralleled Southall's work with tempera.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Joseph Edward Southall continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life, remaining dedicated to his artistic principles and his tempera technique even as artistic fashions changed dramatically around him. He maintained his home and studio in Edgbaston, Birmingham, and continued to find inspiration in the local landscape, his family, and his enduring interests in literature and allegory. Despite declining health in his later years, his commitment to his art remained.

He passed away in Birmingham on November 6, 1944, at the age of 83. His death marked the end of a significant chapter in British art. Memorial exhibitions were held, celebrating his contribution both as an artist and as a man of principle.

Today, Joseph Edward Southall's works are held in numerous public collections, including the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (which has a particularly strong collection), the Tate Britain, the National Portrait Gallery, London, and the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. While he may not have achieved the same level of widespread fame as some of his contemporaries like Augustus John or William Orpen, his reputation has steadily grown, particularly with renewed interest in the Arts and Crafts movement, Pre-Raphaelitism, and early 20th-century figurative painting.

His legacy is multifaceted. He was a master technician who almost single-handedly revived and championed the art of tempera painting in Britain. He was a key figure in the Birmingham Group, contributing to a distinctive regional flowering of the Arts and Crafts ethos. His work offers a unique synthesis of Pre-Raphaelite romanticism, Arts and Crafts integrity, and a personal vision characterized by clarity, luminosity, and quiet conviction. Furthermore, his unwavering commitment to pacifism and social justice, expressed both in his life and his art, provides an inspiring example of an artist deeply engaged with the moral and ethical issues of his time. Joseph Edward Southall remains a testament to the enduring power of art created with skill, passion, and profound integrity.