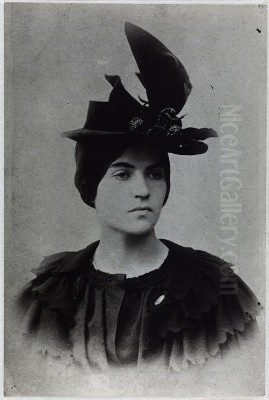

Suzanne Valadon stands as a unique and compelling figure in the narrative of modern art. Born Marie-Clémentine Valadon on September 23, 1865, in Bessines-sur-Gartempe, Haute-Vienne, France, and passing away in Paris on April 7, 1938, her life traversed a remarkable path from poverty and obscurity to artistic recognition. She was not born into privilege or artistic lineage; instead, she forged her identity first as a sought-after artist's model in the vibrant heart of Montmartre and then, against considerable odds, as a respected painter in her own right. Known for her uncompromising depictions, particularly of the female nude, Valadon challenged the conventions of her time and carved out a space for a distinctly female perspective within a male-dominated art world. Her journey is one of resilience, self-determination, and raw artistic talent.

Early Life and Montmartre Beginnings

Valadon's early life was marked by hardship. Born illegitimate to Madeleine Valadon, a laundress, she never knew her father. Mother and daughter moved to the burgeoning artistic neighborhood of Montmartre in Paris, seeking opportunity but finding mostly struggle. Montmartre, perched on a hill overlooking the city, was rapidly becoming the epicenter of avant-garde art, attracting painters, writers, and performers drawn to its cheap rents and bohemian atmosphere. It was a world away from the staid salons of academic art, pulsing with the energy of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and the nascent stirrings of modernism.

Growing up amidst this creative ferment, the young Marie-Clémentine was known for her independent and rebellious spirit. Formal education was brief; poverty dictated the need to work. She held various jobs, but her restless energy found an outlet in the circus. Around the age of 15, she began working as an acrobat, a physically demanding and precarious profession. However, a fall from a trapeze ended this burgeoning career abruptly, forcing her to seek a new path. This injury, while unfortunate, proved serendipitous, redirecting her towards the art world that surrounded her.

Even before her circus stint, Valadon had shown an inclination towards drawing, teaching herself from a young age, reportedly around nine. Living in Montmartre placed her directly in the path of artists who were revolutionizing visual representation. The air buzzed with the names and works of painters capturing modern life, light, and form in new ways. This environment, combined with her innate drive, laid the groundwork for her future, though her entry into the art world would initially be through posing rather than painting.

The Model's Gaze

Following her circus accident, the teenage Valadon, possessing striking features and a captivating presence, found work as an artist's model. This was a common occupation for young women in Montmartre, but Valadon was not merely a passive subject. She quickly became a favorite model for some of the most prominent artists of the era, entering the studios and lives of figures who shaped late 19th and early 20th-century art.

She posed for the Symbolist painter Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, known for his serene, classically inspired murals. She also modeled extensively for Pierre-Auguste Renoir, appearing in celebrated Impressionist works like Dance at Bougival (1883) and Dance in the City (1883). Her image was captured by the incisive eye of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, the chronicler of Montmartre's nightlife and demimonde, who also became a close friend and possibly a lover. He famously gave her the nickname "Suzanne," after the biblical story of Susanna and the Elders, perhaps alluding to her position being observed by older male artists.

Her relationship with Edgar Degas, however, proved the most pivotal for her artistic development. She began modeling for him around the early 1880s. Degas, known for his depictions of dancers, bathers, and modern Parisian life, was notoriously exacting but also perceptive. He recognized Valadon's intelligence and burgeoning artistic talent beyond her role as a model. Modeling provided Valadon not just income but invaluable, albeit informal, art education. She observed techniques, compositional strategies, and the artistic process firsthand in the studios of masters. She absorbed lessons on line, form, and color, developing her critical eye even before she began seriously pursuing her own art.

Mentorship and Self-Discovery

While Valadon was largely self-taught, her interactions with Edgar Degas were crucial. Unlike many artists who might have viewed their models merely as tools, Degas saw potential in Valadon. He noticed her sketches, often done privately after her modeling sessions, and was impressed by their strength and honesty. He actively encouraged her artistic pursuits, offering guidance and critique. This mentorship from an established master was rare, especially for a woman from a working-class background with no formal training.

Degas admired the bold quality of her line work. He instructed her in techniques, particularly in printmaking, and emphasized the importance of keen observation and capturing the essence of a subject. He reportedly called her drawings "terrible and soft," recognizing their power and sensitivity. He became a supporter, purchasing her drawings and introducing her work to other influential figures, including the dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. His validation provided Valadon with crucial confidence and a foothold in the competitive art world.

Degas's influence extended beyond technical advice; he respected her as a fellow artist, an equal in spirit if not yet in reputation. He famously remarked upon seeing her drawings, "You are one of us." This acceptance from a figure of Degas's stature was immensely significant. It affirmed her talent and encouraged her to transition fully from model to creator, to move from being the observed to the observer, wielding the pencil and brush herself. She learned not just how to draw, but how to see with an artist's intensity, a skill honed both by Degas's tutelage and her own sharp intellect.

Forging an Artistic Identity

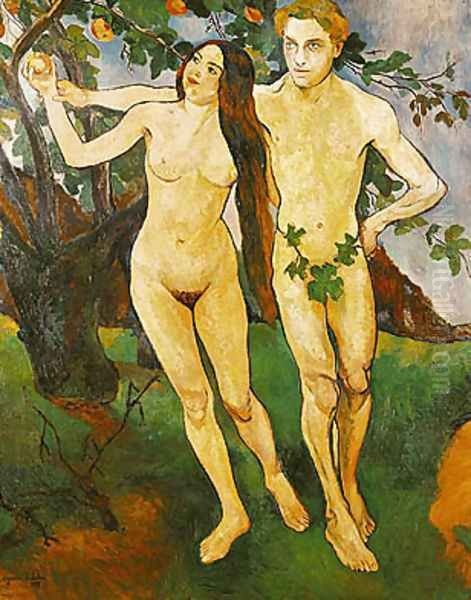

Empowered by Degas's encouragement and her own relentless drive, Suzanne Valadon dedicated herself to painting and drawing. She developed a distinctive style characterized by strong, decisive outlines and a bold use of color, often applied in flat planes. Her work shows an affinity with Post-Impressionist sensibilities, particularly in its departure from naturalistic representation towards more expressive forms, echoing perhaps the linear emphasis of artists like Paul Gauguin or the emotional intensity found in Vincent van Gogh, though her style remained uniquely her own.

There are also clear connections to Fauvism in her vibrant, non-naturalistic color palettes and the raw energy of her compositions, aligning her with contemporaries like Henri Matisse and André Derain. However, Valadon never formally belonged to any specific school or movement. Her art was forged from her experiences, her observations as a model, and her fiercely independent perspective. She focused primarily on the human figure, still lifes, and occasionally landscapes, bringing a directness and psychological depth to her subjects.

A major milestone occurred in 1894 when Valadon became the first woman admitted to exhibit at the prestigious Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. This was a significant achievement, breaking barriers in an institution largely dominated by men. It marked her official arrival as a professional artist. She exhibited regularly throughout her career, including at the Salon d'Automne and the Salon des Indépendants, gradually building her reputation despite the challenges faced by female artists at the time. Her work stood out for its lack of sentimentality and its powerful, often stark, portrayal of the human form.

Challenging Conventions: The Female Nude

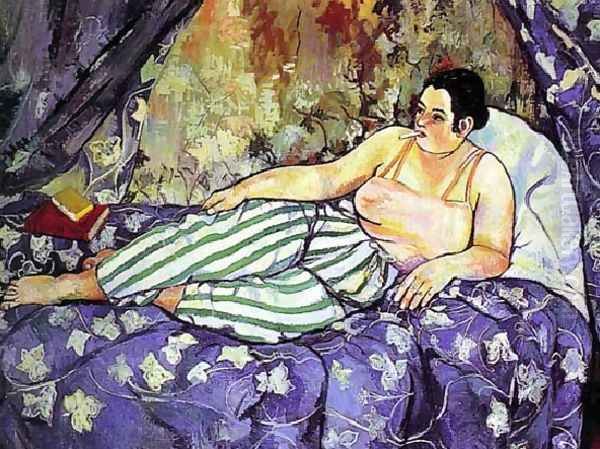

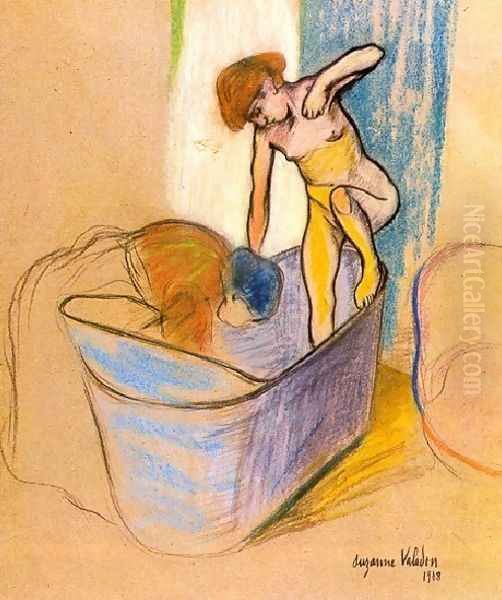

Suzanne Valadon is perhaps best known for her revolutionary approach to the female nude. Throughout art history, the female nude had predominantly been depicted through the lens of the male gaze – often idealized, eroticized, or presented as passive objects of beauty. Valadon, drawing from her own experiences as both a woman and a model, fundamentally challenged these conventions. Her nudes are often unidealized, depicting women with a sense of weight, presence, and psychological complexity.

Her figures are not passive; they are active, often caught in moments of everyday intimacy – bathing, stretching, resting. They possess a tangible physicality, sometimes awkward, sometimes powerful, but always real. Valadon rejected the smooth, perfected surfaces of academic nudes, instead using strong contours and bold colors to define form and convey emotion. Works like Two Figures (1909) present female bodies with an unapologetic directness, focusing on their structure and presence rather than conforming to traditional standards of beauty.

Her masterpiece, The Blue Room (1923), depicts a reclining nude woman, surrounded by vibrant blue patterned fabrics. Unlike odalisques of the past, this figure is robust, seemingly self-possessed, perhaps even defiant, smoking a cigarette and gazing away thoughtfully. She is not presented solely for the viewer's pleasure but exists within her own world. Similarly, Women in White Stockings (1924) offers an intimate yet unsentimental view of female figures. Valadon's nudes were controversial precisely because they offered an alternative perspective, one grounded in female experience and observation, stripping away layers of artifice to reveal a more complex and often challenging reality. She also painted male nudes, further subverting gendered expectations in art.

A Life Entwined with Art

Valadon's life remained deeply embedded in the artistic milieu of Montmartre and Paris. Her personal life was as unconventional and spirited as her art. She had complex relationships with several figures in the art and music world. In 1883, at the age of 18, she gave birth to a son, Maurice. The identity of Maurice's father remains uncertain, though possibilities include several artists she knew; eventually, Miguel Utrillo, a Spanish artist and friend, legally acknowledged paternity in 1891, giving the boy his surname, Maurice Utrillo.

Valadon had a passionate but short-lived affair with the avant-garde composer Erik Satie in the early 1890s. She painted his portrait, and he reportedly proposed marriage after their first night together. Later, in 1896, she married Paul Mousis, a stockbroker, which provided some financial stability but seemed creatively stifling. The marriage eventually dissolved.

In 1909, Valadon began a relationship with André Utter, a painter who was 21 years her junior and a friend of her son, Maurice. This relationship caused a scandal. She divorced Mousis in 1913 and married Utter in 1914. The trio – Valadon, her son Maurice Utrillo, and her husband Utter – formed a complex and often volatile household, sometimes referred to as the "trinité maudite" (cursed trinity). They lived and worked together, exhibiting alongside each other. Valadon continued to frequent the cafes and cabarets that were the social hubs of Montmartre, like the Chat Noir and the Lapin Agile, maintaining connections with artists like Amedeo Modigliani and other figures of the Parisian avant-garde. Her life defied bourgeois norms, reflecting the bohemian spirit of her art.

Mother and Son: The Art of Maurice Utrillo

The relationship between Suzanne Valadon and her son, Maurice Utrillo (1883-1955), is one of the most fascinating and complex dynamics in art history. Maurice struggled with alcoholism from a young age. It was Valadon who encouraged him to take up painting around 1904 as a form of therapy and a potential vocation. She provided his initial instruction, sharing her knowledge of technique and materials.

Maurice Utrillo quickly developed his own distinctive style, becoming famous for his atmospheric paintings of Montmartre street scenes, often characterized by a unique rendering of white buildings and a sense of quiet melancholy. While Valadon's influence can be seen in his early work, particularly in the strong linear structure, his artistic temperament and subject matter diverged significantly from hers. Where Valadon's work pulsed with vibrant color and focused on the human figure, Utrillo's often conveyed solitude and stillness through urban landscapes.

Despite their stylistic differences, mother and son remained closely connected, both personally and professionally, for many years. They exhibited together and supported each other's careers. However, Maurice's struggles with mental health and alcoholism persisted throughout his life, requiring periods of institutionalization. His fame eventually grew, and for a time, particularly in the mid-20th century, Maurice Utrillo's name perhaps eclipsed his mother's in popular recognition. This historical quirk sometimes obscured Valadon's own significant contributions and pioneering role, a situation that later art historical reassessment has sought to correct. Their intertwined lives and careers offer a poignant study of familial bonds, artistic influence, and individual creative paths.

Later Years and Recognition

Suzanne Valadon continued to paint prolifically throughout the 1920s and 1930s, producing some of her most powerful works during this period, including The Blue Room. She held solo exhibitions and participated in group shows, gaining a degree of recognition within the Paris art world. However, she never achieved widespread commercial success comparable to some of her male contemporaries or even her son. Financial difficulties remained a recurring issue.

Her personal life also saw changes. Her relationship with André Utter eventually deteriorated, and they separated, though they did not divorce until shortly before Utter's death. Her relationship with Maurice also became strained later in life, particularly after his marriage to Lucie Valore in 1935, who became protective and perhaps isolating. Valadon's later years were marked by increasing solitude and health problems, including uremia.

Despite these challenges, she remained dedicated to her art until the end. On April 7, 1938, while painting at her easel, Suzanne Valadon suffered a stroke and died later that day in Paris at the age of 72. Her funeral at the Saint-Ouen Cemetery was attended by many prominent figures from the art world, including her friends André Derain and Pablo Picasso, testament to the respect she commanded among her peers. While her passing did not immediately lead to a surge in her market value or popular fame, the foundation for her later reappraisal was laid by the undeniable quality and originality of her life's work.

Legacy and Reappraisal

For several decades after her death, Suzanne Valadon's reputation remained somewhat muted. She was often mentioned primarily in relation to the famous male artists she modeled for or as the mother of Maurice Utrillo. Her bold, often confrontational nudes did not align easily with mid-century tastes, and the narrative of modern art often marginalized female contributors. However, the latter half of the 20th century, particularly with the rise of feminist art history from the 1970s onwards, brought renewed attention to her work.

Scholars and curators began to re-evaluate Valadon not as a peripheral figure but as a significant artist in her own right – a pioneer who defied societal expectations and offered a crucial female perspective on themes traditionally dominated by men. Her unique journey from model to artist was recognized as a powerful story of self-creation. Her unflinching depictions of the female body were reinterpreted not as crude or unflattering, but as honest, empathetic, and subversive acts that challenged the objectification inherent in the traditional male gaze.

Major retrospectives, such as those held at the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia more recently, have solidified her importance. Her work is now celebrated for its technical skill, its emotional depth, and its historical significance as a precursor to later feminist art practices. Valadon's legacy lies in her courage to depict the world, particularly the female experience, with uncompromising honesty and a distinctive artistic vision. She demonstrated that a woman, even one from the margins of society, could seize the tools of art and use them to express a powerful, authentic voice.

Conclusion

Suzanne Valadon's life and art offer a compelling narrative of resilience, transformation, and artistic integrity. Emerging from poverty in the bohemian crucible of Montmartre, she navigated the complex dynamics of the art world first as a model for masters like Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Degas, and then forged her own path as a painter of remarkable power and originality. Her admission to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts and her consistent exhibition record marked her professional success against the odds.

Her enduring contribution lies significantly in her radical reimagining of the female nude, replacing idealized passivity with depictions of strength, complexity, and unvarnished reality. Works like The Blue Room remain potent statements of female self-possession. While her personal life was unconventional, marked by intense relationships with figures like Erik Satie, Maurice Utrillo, and André Utter, it fueled an art that was deeply felt and fiercely independent. Though sometimes overshadowed during her later life and posthumously, Suzanne Valadon's critical reputation has rightfully grown. She is now recognized as a vital figure in modern art, a pioneering woman artist whose bold lines and vibrant colors captured the spirit of her time while challenging its constraints, leaving behind a legacy of defiant beauty and enduring strength.