Introduction to an Artist and His Era

Thomas Bardwell (1704-1767) emerges from the annals of British art history not merely as a painter of portraits, but also as a significant contributor to the technical understanding of his craft. Active during a vibrant period of artistic development in Britain, Bardwell's career unfolded against a backdrop of rising native talent and an increasing demand for portraiture from a burgeoning middle class and established gentry. While he may not occupy the same echelon of fame as some of his more celebrated contemporaries, his work, both on canvas and in print, offers valuable insights into the artistic practices and theoretical concerns of the mid-18th century. His most enduring legacy, beyond his surviving paintings, is his influential treatise, The Practice of Painting and Perspective Made Easy, published in 1756. This publication distinguished him as a thoughtful practitioner keen on demystifying the complexities of oil painting for a wider audience.

The Artistic Climate of 18th-Century Britain

The 18th century in Britain was a period of profound transformation in the arts. The preceding century had been largely dominated by foreign-born artists, such as Sir Anthony van Dyck, Sir Peter Lely, and Sir Godfrey Kneller, who set the standard for portraiture and courtly art. However, the 1700s witnessed a growing confidence and capability among British artists. Portraiture remained the most lucrative and sought-after genre, fueled by a society eager to commemorate its status, achievements, and lineage. This era saw the rise of figures like William Hogarth, whose satirical narratives and "modern moral subjects" carved a unique niche, and later, the towering figures of Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough, who would come to define British painting in the latter half of the century.

The infrastructure for artistic training and exhibition was also evolving. While the Royal Academy of Arts would only be formally established in 1768, shortly after Bardwell's death, the preceding decades saw various informal societies and drawing schools, like the St Martin's Lane Academy, fostering artistic talent. Artists often learned through apprenticeships, by copying Old Masters, or, as Bardwell's book suggests, through dedicated self-study and practical experimentation. The demand for art was not confined to London; provincial centers also supported local artists, and Bardwell himself found patronage across East Anglia and beyond.

Thomas Bardwell: A Biographical Sketch

Born in Bungay, Suffolk, in 1704, Thomas Bardwell's early life and artistic training remain somewhat obscure, a common fate for many artists of the period who did not achieve metropolitan superstardom. It is likely he was largely self-taught or received instruction from a local painter, honing his skills through practice and observation. His career as an itinerant portrait painter saw him working extensively in East Anglia, particularly in Suffolk and Norfolk, but he also undertook commissions in London and other parts of England.

Bardwell's output primarily consisted of portraits, catering to the local gentry, clergy, and prosperous merchant families. These works, while perhaps lacking the dazzling bravura of a Gainsborough or the psychological depth of a Reynolds, were competent, honest likenesses that fulfilled the patrons' desires for a respectable record of their appearance and status. He was active as a painter from at least the 1730s until his death in Norwich in 1767. His will, proved in Norwich, provides some details about his family and possessions, indicating a moderately successful career.

Bardwell's Artistic Style and Representative Works

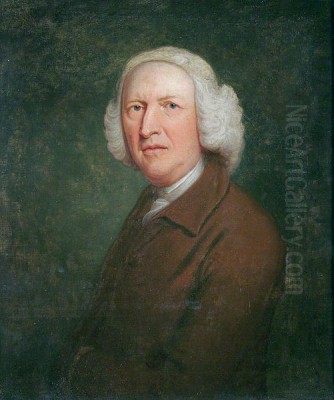

Thomas Bardwell's style is characteristic of much mid-18th-century British portraiture. His approach was generally straightforward, focusing on achieving a good likeness and conveying the social standing of his sitters through their attire and pose. His handling of paint was typically smooth, with attention paid to the rendering of fabrics and facial features. While he may not have been an innovator in terms of composition or painterly technique in the same vein as Hogarth, his work demonstrates a solid understanding of traditional oil painting methods.

Among his known works, portraits such as those of various members of prominent East Anglian families like the Bacon family of Raveningham Hall, or the L'Estrange family of Hunstanton Hall, showcase his abilities. For instance, his portrait of Sir Armine Wodehouse, 5th Baronet (c. 1748, now in the Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery) displays a confident handling of the formal male portrait of the period. Another example, Mary Phipps, is mentioned in modern analyses of his work, highlighting its utility for technical study.

Bardwell also engaged with the tradition of copying or creating works in the style of Old Masters, as evidenced by a piece described as Untitled (Imitation of Peter Paul Rubens). This practice was common, serving both as a learning exercise for the artist and as a way for patrons to acquire versions of famous compositions. His portraits generally avoid excessive flattery, aiming for a dignified representation that would have appealed to his clientele. The overall impression is one of sober competence and a reliable adherence to the conventions of the time.

The Practice of Painting and Perspective Made Easy (1756)

Bardwell's most significant contribution to art history is undoubtedly his treatise, The Practice of Painting and Perspective Made Easy. Published in London in 1756, this book stands out as one of the earliest and most original English-language practical guides to oil painting. In an era when many artistic "secrets" were closely guarded or passed down through workshop traditions, Bardwell's willingness to codify and share his knowledge was noteworthy.

The book was aimed at both aspiring artists and amateurs, offering clear, step-by-step instructions on various aspects of the painter's craft. It covered topics such as the preparation of canvases, the grinding and mixing of pigments, the properties of different oils and varnishes, methods for laying in a portrait, techniques for rendering flesh tones, drapery, and backgrounds, and the principles of linear perspective. Bardwell's approach was eminently practical, born from his own extensive experience at the easel.

The treatise is particularly valuable for its detailed descriptions of the palette and painting process favored by a working artist of the time. He meticulously lists the pigments he used, their preparation, and their application in layers, from underpainting to final glazes. This provides a crucial window into the material culture of 18th-century painting, complementing the visual evidence of surviving artworks. The section on perspective, while perhaps less original than his painting instructions, was nonetheless a useful inclusion for artists needing to create convincing spatial illusions.

Originality and Impact of the Treatise

Bardwell's book was well-received and went through several editions, including a posthumous one in 1773, indicating its sustained utility. Its originality lay in its comprehensive yet accessible approach, specifically tailored to oil painting as practiced in Britain. While earlier treatises existed, many were translations of foreign works or focused on different media. Bardwell's work was grounded in contemporary English practice.

The publication of such a manual contributed to the broader dissemination of artistic knowledge, potentially empowering a wider range of individuals to take up painting. It reflected a growing Enlightenment-era interest in rationalizing and systematizing knowledge across various fields, including the arts. For art historians today, the treatise is an invaluable resource for understanding the technical methods of 18th-century painters, allowing for more informed interpretations of their works and a better appreciation of their material choices. It provides a baseline against which the practices of other artists, both more and less famous, can be compared.

Scientific Analysis: Bardwell's Practice Versus His Precepts

A fascinating aspect of Bardwell's legacy is the opportunity to compare his written instructions with his actual painting practice, thanks to modern scientific analysis. Research involving the examination of pigment samples from his paintings has shed light on this relationship. One notable study analyzed approximately 351 pigment samples taken from fifteen of Bardwell's oil paintings, dating from between 1740 and 1766. This allowed for a reconstruction of his palette and layering techniques.

The findings of such studies generally indicate that Bardwell's actual painting methods were broadly consistent with the advice given in The Practice of Painting and Perspective Made Easy. However, the research also revealed that his practical application was often simpler than the sometimes more elaborate procedures described in his book. This is not altogether surprising; an artist might simplify processes in the daily grind of studio work for efficiency, while a manual might aim to present a more ideal or comprehensive methodology. For example, he might advocate for a complex series of glazes in his text, but in practice, use fewer layers to achieve a similar, if slightly less nuanced, effect.

These analyses confirm his use of a typical 18th-century palette, including pigments like lead white, vermilion, various ochres, Prussian blue (a relatively new pigment at the time, which he championed), and bone black. The study of his paint layers—the imprimatura, underpainting, and finishing touches—corroborates many of the techniques he detailed, offering a tangible link between his theoretical pronouncements and his studio reality. This makes Bardwell a unique case study in the technical art history of the period.

Bardwell in the Context of His Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Bardwell's position, it is useful to consider him alongside other artists active during his lifetime. While he operated primarily as a provincial portraitist, the London art scene was bustling with figures who were shaping the future of British art.

William Hogarth (1697-1764) was a towering figure, known for his satirical prints and paintings that critiqued contemporary society. His robust, direct style and innovative subject matter set him apart.

Thomas Hudson (1701-1779), a leading portrait painter in London, was the master of Joshua Reynolds. Hudson's style was more conventional, influenced by the Kneller tradition but adapting to newer, slightly less formal tastes. Bardwell's work shares some of the straightforwardness of Hudson's less grand portraits.

Allan Ramsay (1713-1784), a Scottish portrait painter, brought a delicate Rococo sensibility and psychological acuity to his work, particularly his female portraits. He was a significant rival to Reynolds for royal patronage.

Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792) would become the first President of the Royal Academy and the dominant force in British portraiture. His "Grand Manner" portraits, rich with art historical allusions, and his influential Discourses on Art set a high intellectual bar for the profession. Bardwell's treatise, though more practical, can be seen as part of a similar impulse to elevate and codify artistic practice.

Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), Reynolds's great rival, was celebrated for his fluid brushwork, sensitivity to character, and his love of landscape painting. His style was more intuitive and less academic than Reynolds's.

Other notable portraitists of the era included Francis Hayman (c. 1708-1776), a versatile artist known for conversation pieces and historical subjects, who also taught Gainsborough; Arthur Devis (1712-1787), famed for his small-scale, slightly stiff but charming conversation pieces and portraits; and George Knapton (1698-1778), known for his portraits of members of the Society of Dilettanti. Later in Bardwell's life, artists like Joseph Wright of Derby (1734-1797), with his dramatic use of chiaroscuro, and George Romney (1734-1802), who became a fashionable rival to Reynolds, were beginning to make their mark.

Bardwell's work, and particularly his book, provided a practical foundation that could be utilized by artists working at various levels, from provincial painters to those aspiring to London success. His treatise offered a systematized approach that was less dependent on the workshop traditions of artists like Jonathan Richardson (1667-1745), whose own writings on art theory were influential earlier in the century.

Bardwell's Palette and Technical Approach

The detailed instructions in Bardwell's treatise regarding pigments and their application are a goldmine for understanding 18th-century oil painting. He advocated for a well-organized palette and systematic layering. His palette included essential colors like Flake White (lead white), Light Ochre, Brown Ochre, Light Red (calcined yellow ochre), Indian Red, Brown Pink, Ivory Black, Blue Black (calcined ivory), and Ultramarine (lapis lazuli, though he also discussed the more affordable Prussian Blue).

He emphasized the importance of the "first sitting" or "dead-colouring," where the basic forms and tones were laid in, often using lean paint. Subsequent layers would build up the richness of color and detail, with glazes (transparent layers of paint) used to modify hues and deepen shadows. His advice on flesh tones was particularly detailed, describing how to achieve lifelike complexions through careful blending and the use of specific color mixtures for lights, halftones, and shadows. For instance, he might suggest a base of white, light red, and a touch of yellow ochre for general flesh, modified with vermilion for ruddier areas, and cooler tones incorporating blue or black for shadows and receding planes.

His promotion of Prussian blue is significant. Discovered in the early 18th century, it was a strong, relatively inexpensive, and permanent blue that quickly became indispensable for artists, replacing or supplementing more costly pigments like ultramarine or smalt. Bardwell's clear instructions on its use would have been valuable to his readers. He also discussed the importance of using appropriate drying oils, like linseed oil and poppy oil, and the dangers of using too much oil, which could lead to yellowing or cracking.

The Role of Perspective in Bardwell's Teaching

Perspective was a cornerstone of academic art training, essential for creating the illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. Bardwell's inclusion of perspective in his treatise underscores its importance for painters, even those primarily focused on portraiture where complex architectural settings might be less common. He provided practical rules for linear perspective, explaining concepts like the horizon line, vanishing points, and how to depict objects receding into the distance.

This knowledge was crucial not only for backgrounds but also for correctly rendering the human figure and its placement within a believable space. While portraitists like Bardwell might not have needed the elaborate perspectival schemes of history painters or veduta artists like Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal, 1697-1768), a working understanding of perspective was vital for professionalism. His instructions aimed to make these principles accessible, removing some of the mystique that often surrounded them.

Bardwell's Legacy and Art Historical Position

Thomas Bardwell's position in art history is twofold. As a painter, he represents the competent and diligent provincial artist who served a vital role in disseminating artistic taste and practice beyond the metropolitan center. His portraits are valuable historical documents, preserving the likenesses of a generation of East Anglian society. While his canvases may not consistently reach the artistic heights of his most famous contemporaries, they are solid examples of mid-18th-century British portraiture.

His more enduring legacy, however, lies in his authorship of The Practice of Painting and Perspective Made Easy. This book secured him a place in the history of art technique and theory. It remains a primary source for understanding 18th-century oil painting methods, offering insights that are not always apparent from visual examination of paintings alone. The fact that it was studied and compared with his actual works through scientific analysis further enhances its value, providing a rare bridge between artistic theory and studio practice of the period.

He was not a founder of a major school, nor did he revolutionize artistic style in the manner of a Turner or Constable later on. Yet, by codifying and sharing his practical knowledge, Bardwell contributed to the professionalization and democratization of art practice in Britain. His work reminds us that art history is not solely composed of towering geniuses but also of dedicated practitioners who sustain and transmit the craft.

Conclusion: A Painter of Substance and a Teacher of Value

Thomas Bardwell of Bungay was an artist of his time, a skilled portraitist who diligently served his patrons and a thoughtful author who sought to share his accumulated knowledge. In the bustling art world of 18th-century Britain, which saw the emergence of truly native schools of painting and the establishment of institutions like the Royal Academy, Bardwell carved out a respectable career. His paintings offer a glimpse into the faces and aspirations of the provincial gentry and middle class.

His treatise, The Practice of Painting and Perspective Made Easy, transcends his individual artistic output, providing an invaluable window into the technical heart of 18th-century oil painting. It stands as a testament to his desire to make the art of painting more accessible and understandable, reflecting an Enlightenment spirit of inquiry and dissemination. For art historians, conservators, and practicing artists interested in historical techniques, Bardwell's book, corroborated and sometimes nuanced by scientific study of his paintings, remains a significant and illuminating resource. He may not be the most celebrated name from his era, but Thomas Bardwell's contribution to the fabric of British art history is undeniable and worthy of continued study and appreciation.