Eanger Irving Couse stands as a significant figure in the annals of American art, particularly renowned for his sensitive and atmospheric depictions of Native American life in the early 20th century. Born in Saginaw, Michigan, in 1866, Couse developed an early fascination with the indigenous cultures near his home, an interest that would blossom into the defining theme of his artistic career. As a key member of the Taos Society of Artists, he not only shaped his own legacy but also contributed significantly to the establishment of Taos, New Mexico, as a vital center for American art. His work, characterized by a Tonalist sensibility and a deep respect for his subjects, offers a window into the world of the Pueblo people, rendered with warmth, dignity, and a masterful handling of light.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Eanger Irving Couse's journey into art began in his childhood home of Saginaw, Michigan. Born into a family that was not initially oriented towards the arts, the young Couse found inspiration in his surroundings. Saginaw was located near lands inhabited by the Chippewa (Ojibwa) people, and Couse was captivated by their culture and way of life. He spent hours observing and sketching their daily activities, their dwellings, and the people themselves. This early immersion in Native American life laid the foundation for his lifelong artistic focus. His innate talent was evident, and he pursued formal training to hone his skills.

His quest for artistic education led him first to the Art Institute of Chicago, where he studied briefly. Seeking more rigorous instruction, he moved to New York City to enroll at the prestigious National Academy of Design. These formative years provided him with essential technical skills in drawing and painting. However, like many ambitious American artists of his generation, Couse felt the pull of Paris, then the undisputed center of the Western art world. In 1886, he embarked for France, eager to absorb the lessons of the European masters.

Parisian Training and Influences

In Paris, Couse enrolled at the Académie Julian, a renowned private art school that attracted students from across the globe. There, he studied under influential academic painters, most notably Tony Robert-Fleury and William-Adolphe Bouguereau. These instructors were masters of the French Academic tradition, emphasizing precise draughtsmanship, idealized forms, and carefully finished surfaces. Couse absorbed these technical lessons, developing a strong command of anatomy and composition. His time in Paris exposed him to various artistic currents, including the burgeoning Impressionist movement, although his own style would lean more towards the subtle nuances of Tonalism.

Paris was not only a place of artistic growth but also personal significance. It was during his studies there that Couse met Virginia Walker, a fellow American art student. They married in 1889, and Virginia became a vital partner and supporter throughout his life and career. Her presence and encouragement undoubtedly played a role in his artistic development. After several years abroad, including time spent painting peasants in the French countryside, Couse and his wife returned to the United States, eventually settling for a time on a farm owned by her family in Washington state. During this period, he painted the Klikitat people of the region.

The Lure of Taos

The most significant turning point in Couse's artistic life occurred in 1902. His friend and fellow artist, Ernest Blumenschein, who had discovered the unique beauty and artistic potential of Taos, New Mexico, a few years earlier, urged Couse to visit. Blumenschein, along with Bert Geer Phillips, had already begun to establish an artistic presence in the remote village. Intrigued by Blumenschein's descriptions of the stunning landscape, the unique adobe architecture, and the rich culture of the Taos Pueblo Indians, Couse made his first trip to the Southwest.

He was immediately captivated. The high desert light, the dramatic mountain backdrop, and the ancient, multi-storied pueblo structure offered a wealth of visual inspiration unlike anything he had experienced before. Most importantly, the Taos Pueblo people, with their distinct traditions and enduring way of life, resonated deeply with the interest he had cultivated since childhood. The region offered a unique combination of picturesque scenery and compelling human subjects, seemingly untouched by the rapid industrialization transforming much of America.

From 1902 until 1927, Couse and his family spent nearly every summer and autumn in Taos, returning to New York City for the winters where he maintained a studio and connections with the art market. The pull of Taos proved irresistible, however, and in 1928, they made it their permanent home. This move solidified his identity as a painter of the Southwest and allowed for deeper immersion in the community and culture he depicted.

Artistic Style: Tonalism and the Taos Subject

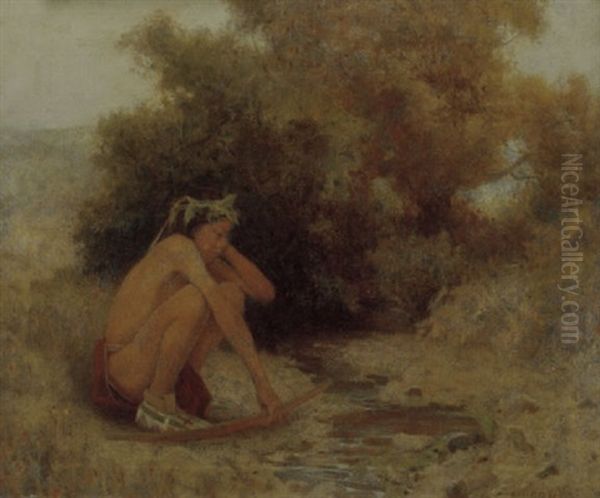

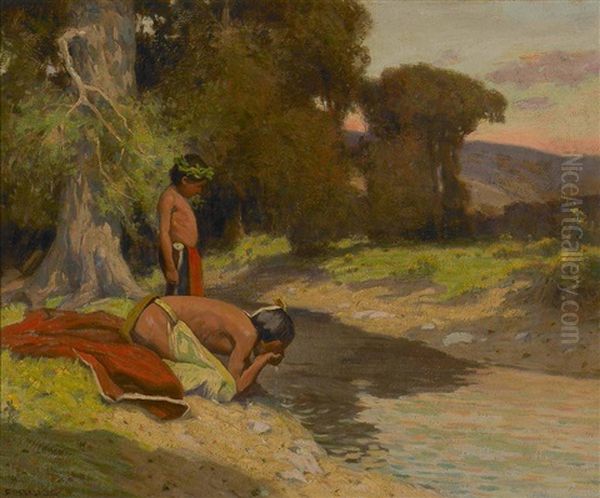

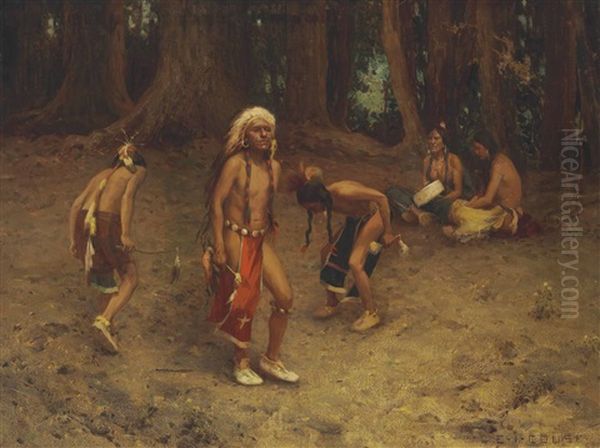

Couse's mature artistic style is often associated with Tonalism, an American art movement that emerged in the late 19th century, characterized by its emphasis on mood, atmosphere, and soft, harmonious color palettes. While influenced by his academic training in Paris, Couse adapted these techniques to suit his Southwestern subjects. He became particularly known for his depictions of Native Americans in quiet, contemplative moments, often illuminated by the warm glow of firelight or the soft light of dawn or twilight.

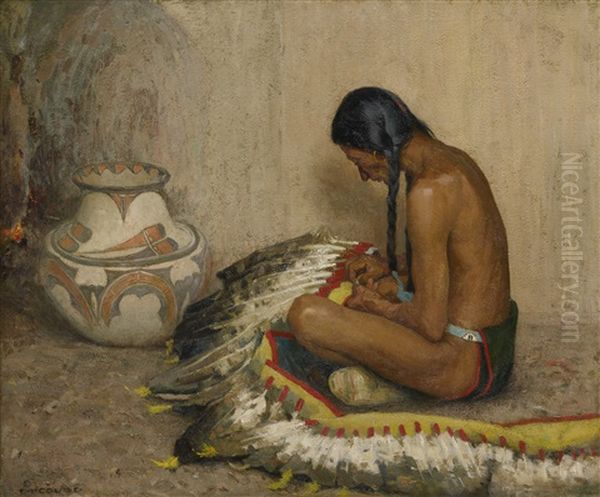

His paintings rarely depicted scenes of conflict or overt action, a contrast to some other painters of the West like Frederic Remington or Charles M. Russell, who often focused on the drama of cowboy life or historical battles. Instead, Couse focused on the peaceful, domestic, and spiritual aspects of Pueblo life. His subjects are often shown engaged in traditional activities like pottery making, weaving, hunting, or simply resting by a stream or campfire. He aimed to convey a sense of dignity, timelessness, and harmony between the people and their environment.

Couse employed a relatively dark palette, using subtle gradations of tone and color to create depth and atmosphere. His brushwork was controlled yet expressive, allowing for both detailed rendering of figures and objects and a softer treatment of backgrounds and light effects. Firelight scenes became a hallmark of his work, allowing him to explore dramatic contrasts of light and shadow and imbue his paintings with a sense of intimacy and mystery. While sometimes idealized, his portrayals were rooted in careful observation and a genuine sympathy for his subjects.

It is important to note that while Couse strove for authenticity in spirit, his work, like that of many artists of his era depicting Native cultures, sometimes prioritized aesthetic composition and romantic sentiment over strict ethnographic accuracy. He often used studio props and posed models, creating compositions that conveyed a particular mood or idea rather than documenting a specific event precisely as it occurred. His primary goal was to capture what he perceived as the inherent poetry and humanity of the Taos people.

Masterworks and Recognition

Throughout his career, Eanger Irving Couse produced a significant body of work, with several paintings achieving iconic status within the genre of Western American art. One of his most celebrated works is Elk-Foot of the Taos Tribe (1909). This striking portrait depicts a Taos Pueblo man named Jerry Mirabal (Elk-Foot) seated contemplatively, holding a decorated jar. The painting exemplifies Couse's skill in capturing individual character and his masterful use of light and shadow to create a powerful, dignified image. It was purchased for the Smithsonian American Art Museum's collection, signifying its national importance.

Another well-known theme is represented by paintings often titled variations of The Brook or By the Stream, showing figures resting or fetching water near Taos Pueblo's sacred river. These works emphasize the connection between the people and their natural environment, rendered with Couse's characteristic Tonalist atmosphere. The Harvest Song represents an earlier phase but shows his developing interest in depicting Native Americans engaged in traditional, peaceful activities.

His firelight scenes, such as Mending the War Bonnet or The Pottery Decorator, were immensely popular. These paintings allowed Couse to showcase his technical skill in rendering the complex interplay of light and shadow cast by flames, creating intimate and evocative portrayals of domestic life and craftsmanship. Works like Sunlight/Sunshine (c. 1919) and Twilight, Taos Pueblo demonstrate his ability to capture the unique quality of light in the New Mexico landscape at different times of day, bathing the adobe structures and figures in warm or cool hues.

Couse achieved considerable success and recognition during his lifetime. He was elected an Associate of the National Academy of Design in 1902 and a full Academician in 1911. His paintings won numerous awards at major exhibitions, including the prestigious Carnegie Prize. His work was widely reproduced, notably through a long-standing commission from the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway for their annual promotional calendars, which brought his images of idealized Pueblo life to a vast audience across America. His paintings were acquired by major institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the National Gallery of Art, the Dallas Museum of Art, and many others, cementing his place in prominent public collections.

The Taos Society of Artists

Eanger Irving Couse played a pivotal role in the formation and success of the Taos Society of Artists (TSA). Founded formally in 1915, the society brought together a group of painters who were drawn to Taos for its unique artistic inspiration. Couse was not only a founding member but was also elected as the society's first president, a testament to the respect he commanded among his peers.

The initial founding members, besides Couse, were Ernest Blumenschein, Joseph Henry Sharp, Bert Geer Phillips, Oscar E. Berninghaus, and W. Herbert "Buck" Dunton. Later members included Victor Higgins, Walter Ufer, and Catharine Critcher, among others. The society's primary aim was to promote the art of its members and the unique character of the Southwest through organized traveling exhibitions sent to major cities across the United States.

These exhibitions were highly successful, generating sales, critical acclaim, and significantly raising the national profile of Taos as an art colony. The TSA provided a structure for mutual support and collective marketing, benefiting all its members. Couse's established reputation and connections in the New York art world were valuable assets to the fledgling society. The group maintained a cohesive identity for over a decade, despite the diverse styles and personalities of its members, before disbanding in 1927 as its members achieved individual success and the need for collective promotion lessened. The TSA remains one of the most influential regional art associations in American history.

Relationships and Collaborations

Life in the small, relatively isolated village of Taos fostered close relationships among the artists. Couse developed particularly strong bonds with several of his colleagues. His friendship with Ernest Blumenschein was foundational, as it was Blumenschein who first brought him to Taos. They remained lifelong colleagues within the TSA.

His relationship with Joseph Henry Sharp was especially close. Sharp, often considered the spiritual father of the Taos art colony, had been painting Native American subjects even longer than Couse. For many years, their studios in Taos were adjacent, sharing a common wall, which facilitated frequent interaction and exchange of ideas. They also shared patrons; the industrialist John D. Rockefeller, for instance, was known to visit both studios and acquired works from Couse. This proximity and shared artistic focus created a strong professional and personal connection.

Beyond the core TSA members, Couse interacted with other figures in the broader Taos art scene and the wider art world. He collaborated, for example, with the renowned photographer Edward S. Curtis, who dedicated his life to documenting Native American cultures. They participated together in an exhibition at the National Arts Club in New York City, aimed at presenting a more accurate and dignified view of Native Americans than the prevailing stereotypes. The collaborative spirit extended to sharing models and discussing techniques, contributing to the vibrant artistic environment of Taos, which later attracted artists like Nicolai Fechin and Leon Gaspard.

Studio Life and Artistic Process

Couse's studio in Taos became a central part of his identity and artistic practice. He eventually acquired and adapted historic adobe structures near the Taos Plaza for his home and workspace. This complex, now part of the Couse-Sharp Historic Site, provides invaluable insight into his working methods. The studio was filled with Native American artifacts – pottery, blankets, drums, clothing, and beadwork – which he used as props in his paintings to enhance authenticity and visual interest.

Finding models among the Taos Pueblo people was sometimes challenging. As noted in some accounts, there was a degree of superstition or reluctance among some individuals about having their likeness captured. However, Couse developed long-standing relationships with several individuals who modeled for him regularly, including Ben Lujan and Geronimo Gomez. He treated his models with respect and paid them fairly for their time, fostering a sense of trust.

His process typically involved posing his models within the studio, carefully arranging the composition and lighting. He often worked from preliminary sketches and studies, meticulously planning his canvases. The firelight scenes, in particular, required careful management of light sources to achieve the desired dramatic and atmospheric effects. His studio space, preserved today much as he left it, reflects this methodical yet deeply felt approach to painting. The adjacent gardens, cultivated by his wife Virginia, also became part of the property's charm, leading to the site being affectionately known as the "Mother Garden."

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Eanger Irving Couse remained an active painter well into his later years, continuing to explore his cherished themes of Taos Pueblo life. He maintained his national reputation, and his works remained popular with collectors and the public. He continued to participate in exhibitions and contribute to the artistic life of Taos even after the formal dissolution of the Taos Society of Artists.

He passed away in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 1936, at the age of 69, leaving behind a substantial body of work and a significant legacy. His contribution to American art extends beyond his individual paintings. As a founding member and the first president of the TSA, he was instrumental in establishing Taos as a major art center and in bringing the art of the Southwest to national attention. His sympathetic and dignified portrayals of Native Americans, while viewed through the lens of his time, offered a counter-narrative to more negative or stereotypical depictions.

Today, Couse's home and studio in Taos are preserved as part of the Couse-Sharp Historic Site, a National Historic Landmark. The site serves as a museum and research center, offering visitors a unique glimpse into the lives and working environments of two seminal Taos artists. His granddaughter, Virginia Couse Leavitt, became an important historian of his life and work, contributing significantly to the understanding of his career and the concept of the "Couse magic" – the unique confluence of place, time, and spirit that defined his Taos experience. Eanger Irving Couse's paintings continue to be admired for their technical skill, atmospheric beauty, and their enduring portrayal of the spirit of the Taos Pueblo.

Conclusion

Eanger Irving Couse occupies a distinct and respected place in American art history. His journey from a childhood fascination with the Chippewa in Michigan to becoming a leading figure in the Taos art colony is a testament to his dedication and singular vision. Through his Tonalist style, he captured the quiet dignity and spiritual essence of the Taos Pueblo people, creating images that resonated deeply with audiences of his time and continue to do so today. His leadership in the Taos Society of Artists helped shape the course of Western American art, establishing the Southwest as a vital region for artistic exploration. While interpretations of his work may evolve, his legacy as a masterful painter of light, atmosphere, and the human spirit endures.