Introduction: An Unconventional Vision

Thomas Chambers stands as a fascinating and somewhat enigmatic figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century American art. Born in England in 1808, he emigrated to the United States, where he forged a unique artistic path, primarily as a painter of landscapes and marine scenes. Active during a period dominated by the Hudson River School's detailed realism, Chambers offered a strikingly different vision, characterized by bold colors, simplified forms, and a powerful decorative sensibility. Though largely overlooked during his lifetime, his work was rediscovered in the twentieth century, earning him recognition as a significant precursor to modernism and a key figure in American folk art. His paintings, vibrant and rhythmically composed, capture the American scene with an untutored yet compelling energy.

Chambers' journey from the maritime town of Whitby, England, to the bustling art centers of the northeastern United States reflects the transatlantic currents that shaped American culture in the nineteenth century. He brought with him a visual inheritance possibly influenced by maritime traditions and popular prints, which he transformed through his distinctive style. His work occupies a unique space, borrowing from academic conventions while simultaneously subverting them with a naive directness and an emphasis on pattern and bold design over naturalistic representation. This blend of influences and his departure from prevailing artistic norms make Chambers a subject of enduring interest for art historians and enthusiasts alike.

Early Life and Transatlantic Journey

Thomas Chambers was born in Whitby, a coastal town in North Yorkshire, England, in 1808. His family background was intertwined with the sea; his father was a merchant sailor, and his mother worked as a laundress. This maritime environment likely provided early exposure to the ships and seascapes that would later feature prominently in his art. Notably, Thomas was the younger brother of George Chambers (1803-1840), who achieved considerable recognition in England as a talented marine painter. While the extent of George's direct influence or training on Thomas remains speculative, growing up in a family with artistic and seafaring connections undoubtedly shaped his path.

In 1832, seeking opportunities across the Atlantic, Thomas Chambers emigrated to the United States. He initially settled in New York City, a burgeoning metropolis and a growing center for the arts. Records indicate his presence and activity as a painter from around 1834. Over the subsequent decades, until his presumed death around 1866 or shortly thereafter, Chambers worked not only in New York but also spent significant periods in Boston, Massachusetts, and Albany, New York. This itinerant career placed him within the orbit of major artistic developments, yet he maintained a distinct stylistic independence throughout his working life.

A Distinctive Artistic Style

The most striking aspect of Thomas Chambers' art is its unique and highly recognizable style. Departing significantly from the meticulous realism favored by many of his American contemporaries, particularly the Hudson River School painters, Chambers embraced a bolder, more stylized approach. His work is characterized by the use of vibrant, often unmodulated, flat planes of color. He employed strong contrasts between light and shadow, not necessarily to create realistic depth, but rather to enhance the dramatic impact and decorative quality of the composition.

Chambers' paintings often exhibit a strong sense of rhythm and pattern. Forms are simplified, outlines are bold and clear, and the overall effect is often two-dimensional, emphasizing surface design over spatial illusion. Trees might be rendered as repeating, almost abstract shapes, while waves curl in stylized, energetic patterns. This approach lends his work a naive or "primitive" quality, a term often used in relation to folk art. However, his compositions are often complex and dynamically balanced, suggesting a conscious artistic choice rather than a lack of technical skill. He seemed less interested in literal transcription of nature and more focused on creating visually exciting, decorative images.

His technique often involved working from existing sources, particularly popular prints, such as those found in publications like American Scenery illustrated by William Henry Bartlett. Chambers would adapt these black-and-white engravings, simplifying the details, exaggerating certain features, and infusing them with his characteristic bold color and rhythmic energy. This process transformed the often topographically accurate but somewhat staid prints into lively, personal interpretations. His ability to imbue these borrowed compositions with his unique vision is a testament to his artistic originality.

The overall effect of Chambers' style is one of energy, drama, and visual immediacy. His landscapes and seascapes are not quiet meditations on nature but vibrant declarations. The strong colors, dynamic compositions, and stylized forms create a world that is both recognizable and distinctly his own. This departure from academic norms and his embrace of a more direct, decorative language mark him as an important figure in the development of a uniquely American artistic voice, one that resonated with folk traditions while anticipating aspects of later modern art movements.

Dominant Themes: Land and Sea

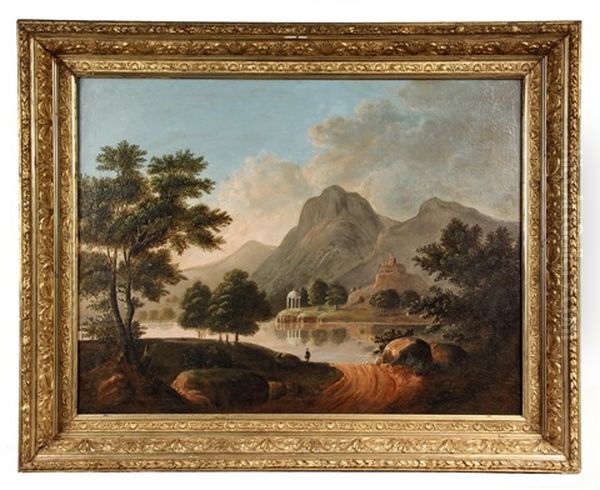

Thomas Chambers focused his artistic output primarily on two major themes: landscapes and marine scenes. His depictions of the American landscape, particularly the Hudson River Valley, form a significant part of his oeuvre. Unlike the detailed, atmospheric renderings of Hudson River School painters like Thomas Cole or Asher B. Durand, Chambers' landscapes emphasize bold patterns, vibrant color, and dramatic compositions. Views of locations like West Point or villas along the Hudson are transformed into dynamic designs, where rolling hills, stylized trees, and architectural elements are arranged for maximum visual impact.

His famous depictions of Niagara Falls, such as Niagara Falls from the American Side, showcase his distinctive approach. Rather than focusing on sublime grandeur through meticulous detail, Chambers captures the power and energy of the falls through simplified forms, strong contrasts, and rhythmic representations of cascading water and spray. The effect is less about topographical accuracy and more about conveying the raw, dynamic force of nature in a visually arresting manner. These landscapes possess a decorative charm and an almost theatrical quality.

Marine painting was another central theme for Chambers, likely influenced by his upbringing in a maritime town and perhaps by his brother George's success in the genre. He painted bustling harbor scenes, such as Boston Harbor, capturing the activity of ships against simplified backdrops. Ship portraits and dramatic naval engagements were also subjects he tackled. His most celebrated work in this genre is arguably The Constitution and the Guerriere, depicting the famous War of 1812 battle. Here, the ships are rendered with a certain naive robustness, and the sea churns with stylized energy, highlighting the drama of the conflict through bold design rather than realistic detail.

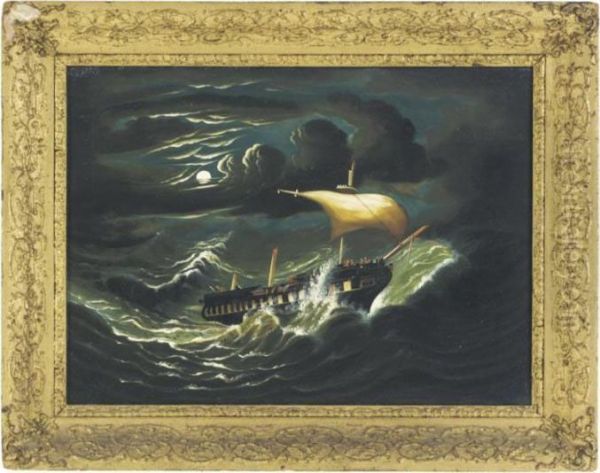

Other marine works, like Shipping off a Coast or Felucca of Gibraltar, demonstrate his consistent approach: simplified forms, strong outlines, vibrant colors, and a focus on the rhythmic patterns of waves and sails. Whether depicting tranquil harbors, dramatic storms like Guardship in a Storm, or specific vessels, Chambers brought his unique decorative and energetic style to the maritime world, creating images that are both informative and visually captivating in their unconventional way. His interest extended to exotic locales as well, as seen in works like Mount Vesuvius, likely based on prints but infused with his characteristic dramatic flair.

Representative Works

Several key paintings exemplify Thomas Chambers' unique style and thematic concerns.

The Constitution and the Guerriere (c. 1840-1850, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York): This iconic naval battle scene is perhaps Chambers' most famous work. It depicts the War of 1812 engagement between the USS Constitution and HMS Guerriere. Chambers simplifies the forms of the ships and rigging, emphasizing their bulk and the dramatic action. The waves are rendered as stylized, rhythmic patterns of dark and light, and the sky is treated with bold color contrasts. The overall effect is one of dramatic intensity achieved through design and color rather than precise nautical detail, showcasing his folk-art sensibility applied to a historical subject.

Boston Harbor (c. 1843-1845, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.): This painting offers a panoramic view of the busy harbor. Chambers includes numerous vessels, simplified architectural elements of the city skyline, and figures on the foreground shore. Again, the emphasis is on pattern and vibrant color. The water is depicted with characteristic rhythmic waves, and the clouds are rendered as bold, decorative shapes. It captures the energy and activity of the port through a lively, stylized composition rather than detailed topographical accuracy.

Niagara Falls from the American Side (c. 1843-1845, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford): One of several views Chambers painted of this natural wonder, this work highlights his approach to landscape. The immense power of the falls is conveyed through bold, simplified masses of water and rock, rendered in strong contrasting tones. The spray rises in stylized plumes, and the surrounding foliage is treated with decorative repetition. It’s a powerful interpretation that prioritizes visual energy and pattern over the sublime atmosphere sought by his Hudson River School contemporaries.

Villa on the Hudson Near Weehawken (New-York Historical Society): This landscape demonstrates Chambers' treatment of architectural subjects within nature. The villa itself is rendered with a certain charming simplicity, nestled within a landscape characterized by rolling hills and distinctively stylized trees. The composition employs strong diagonals and curves, creating a dynamic rhythm across the canvas. The vibrant greens, blues, and whites contribute to the painting's lively, decorative quality.

Mount Vesuvius (c. 1843-1860): Likely based on a print source, this dramatic scene of the erupting volcano allowed Chambers to indulge his flair for strong contrasts and vibrant color. The fiery eruption against a dark sky, the stylized depiction of lava flows, and the dramatic lighting showcase his ability to transform a potentially conventional subject into a uniquely energetic and visually striking image, emphasizing the theatrical potential of the scene.

These works, among others like Shipping off a Coast, View of Nahant, and Felucca of Gibraltar, consistently demonstrate Chambers' artistic personality: a love for bold color, rhythmic design, simplified forms, and a departure from academic naturalism towards a more direct, decorative, and energetic vision of the world.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Thomas Chambers worked during a vibrant period in American art history, largely dominated by the Hudson River School. This group, including prominent figures like Thomas Cole (1801-1848), Asher B. Durand (1796-1886), and later Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900) and Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902), focused on detailed, often idealized, and sublime representations of the American landscape. They sought to capture the grandeur and spiritual essence of nature through meticulous observation and atmospheric effects, often drawing heavily on European academic traditions. Chambers' work stands in stark contrast to this mainstream approach.

While Chambers likely saw the work of Hudson River School painters, his style shows little direct influence from their detailed realism. He shared their interest in American scenery, particularly the Hudson River Valley and Niagara Falls, but his interpretation was radically different. Some art historians suggest influences from earlier or contemporary marine painters like Thomas Birch (1779-1851), who also depicted naval scenes and coastal views, albeit with a more traditional technique. The work of Thomas Doughty (1793-1856), an early landscape painter associated with the Hudson River School but sometimes possessing a softer, more lyrical style, might also have been known to Chambers.

Chambers' connection to print sources, particularly those after William Henry Bartlett (1809-1854), is well-documented. Interestingly, the French-born painter Victor de Grailly (1804-1889) also frequently copied Bartlett's views of America, but de Grailly's versions maintained a smoother, more conventional finish compared to Chambers' bold stylizations. This comparison highlights Chambers' deliberate transformation of source material.

His style aligns more closely with what is now termed American folk or naive art. Contemporaries working in related veins, though with distinct styles and subjects, include Edward Hicks (1780-1849), famous for his allegorical "Peaceable Kingdom" paintings, and itinerant portrait painters like William Matthew Prior (1806-1873) and Sturtevant Hamblen (1809-1884), who often offered portraits in varying degrees of finish and stylization. While Chambers focused on landscape and marine subjects, his simplified forms, flat colors, and emphasis on pattern share characteristics with these folk traditions.

Other notable American artists active during Chambers' career include the portraitist Thomas Sully (1783-1872), known for his elegant and fluid style influenced by British portraiture, and Jacob Eichholtz (1776-1842), another prominent portrait painter based in Pennsylvania. George Catlin (1796-1872) was documenting Native American life with ethnographic detail and artistic flair. Even Chambers' own brother, George Chambers (1803-1840), the successful English marine painter, provides context, though Thomas forged a distinctly different, less academic path in America. The renowned marine painter Fitz Henry Lane (1804-1865), known for his luminist style, was also a contemporary, though his meticulous, light-filled canvases offer a different sensibility entirely. Chambers navigated this diverse artistic landscape, carving out a niche that was uniquely his own.

Reception, Rediscovery, and Legacy

During his lifetime, Thomas Chambers appears to have achieved only modest recognition and likely operated outside the established art institutions like the National Academy of Design. There is little evidence of him exhibiting widely or receiving critical attention from the mainstream art press of the day. His name and work largely faded into obscurity after his death around the mid-1860s. For decades, his paintings, often unsigned, were either unattributed or misattributed. Questions even arose about whether "T. Chambers" was a real person or perhaps a trade name.

The rediscovery and appreciation of Thomas Chambers began in the twentieth century, fueled by a growing interest in American folk art and non-academic traditions. Art historians and collectors began to identify a distinctive group of bold, colorful landscapes and marine paintings. The discovery of signed and dated works, such as Constitution and Guerriere, helped solidify his identity and reconstruct his career. A pivotal moment came in 1942 with the exhibition "T. Chambers, First American Modern" at the Macbeth Gallery in New York City. This exhibition, and the accompanying catalog, championed Chambers as a proto-modernist, praising his bold designs, abstract tendencies, and departure from realism.

This "First American Modern" label, while perhaps an overstatement in literal terms, captured the essence of his appeal to twentieth-century eyes: his work seemed to anticipate later artistic developments that prioritized expressive color and flattened forms over illusionistic representation. His paintings began to be acquired by major museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Fenimore Art Museum, often housed within collections of American folk art. His inclusion in important surveys and exhibitions of folk art further cemented his reputation.

Today, Thomas Chambers is recognized as a significant figure in nineteenth-century American art, valued for his unique style that bridges folk and formal traditions. The "primitive" or "naive" qualities once seen as limitations are now appreciated for their directness, energy, and decorative power. He is understood not simply as an untrained artist, but as a painter with a distinct vision who adapted popular imagery and landscape conventions to create something personal and visually compelling. His work offers a vibrant counterpoint to the dominant Hudson River School aesthetic, enriching our understanding of the diversity of artistic expression in nineteenth-century America. His bold colors and rhythmic compositions continue to attract viewers with their enduring vitality.

Conclusion: A Unique Voice in American Art

Thomas Chambers remains a compelling figure whose work defies easy categorization. An English immigrant who absorbed and transformed aspects of the American scene, he operated largely outside the academic mainstream of his time. His paintings, characterized by their dazzling color, strong patterns, simplified forms, and dramatic energy, offer a unique and vibrant perspective on the landscapes and maritime life of the mid-nineteenth century United States. While contemporaries like the Hudson River School painters sought sublime realism, Chambers pursued a path marked by decorative boldness and a style often associated with folk art traditions.

His obscurity during his lifetime contrasts sharply with his posthumous recognition as a significant and original talent. The rediscovery of his work in the twentieth century brought appreciation for his unconventional techniques and his seemingly intuitive grasp of design principles that resonated with modern aesthetics. Whether viewed as a folk artist, a naive painter, or an early precursor to modernism, Chambers carved out a distinctive niche. His interpretations of popular prints and familiar American scenes are infused with a personal vision and an undeniable visual dynamism.

The legacy of Thomas Chambers lies in his vibrant canvases, which continue to engage viewers with their directness and decorative appeal. He reminds us that the story of American art is richer and more varied than the dominant narratives often suggest. His work stands as a testament to the power of individual vision and the enduring appeal of art that prioritizes expressive force and bold design. Thomas Chambers offers a colorful and energetic chapter in the visual history of America, a unique voice that still speaks with clarity and charm.