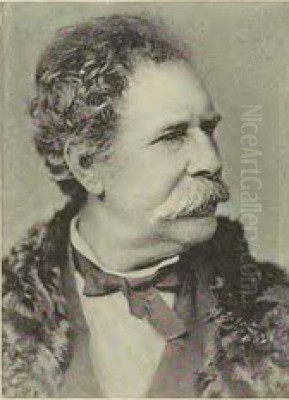

William Louis Sonntag Sr. (1822–1900) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century American art. Primarily associated with the later generation of the Hudson River School, Sonntag carved a distinct niche for himself through his dramatic and often idealized depictions of the American wilderness, complemented by romanticized visions inspired by his travels in Europe, particularly Italy. His long and productive career spanned a transformative period in American art, witnessing the zenith of romantic landscape painting and the emergence of new artistic currents.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Cincinnati

Born on March 2, 1822, near East Liberty, Pennsylvania, a small settlement close to Pittsburgh, William Louis Sonntag moved with his family at a young age to Cincinnati, Ohio. During the 1830s and 1840s, Cincinnati was burgeoning as a major cultural and economic hub in the American West, often dubbed the "Athens of the West." It provided a fertile ground for artistic development, though Sonntag's path was not initially straightforward.

His father, Charles Sonntag, a merchant, strongly disapproved of his son's artistic inclinations, hoping he would pursue a more conventional and financially secure career. Despite this paternal opposition, William Louis Sonntag was resolute in his passion for art. Largely self-taught in his formative years, he diligently honed his skills, seeking out opportunities to learn and observe. His determination led him to eventually study, albeit perhaps briefly, at the Cincinnati Academy of Fine Arts in the early 1840s.

During this period in Cincinnati, Sonntag began to make connections within the local art community. A pivotal encounter was with Godfrey Nicholas Frankenstein (often known as Godfrey N. Frankel), another aspiring artist who became a friend and likely influenced Sonntag's early development. Cincinnati's vibrant artistic milieu also included figures like Worthington Whittredge, who would later, like Sonntag, move east and achieve national recognition, and the talented African American painter Robert S. Duncanson, with whom Sonntag would later collaborate.

The Hudson River School Connection

Sonntag's artistic identity is inextricably linked to the Hudson River School, America's first major school of landscape painting. While not geographically confined to the Hudson River Valley, the school's artists shared a common reverence for the American landscape, viewing it as a source of national pride and spiritual renewal. They sought to capture the grandeur, beauty, and sometimes the untamed wildness of the continent.

The movement is often divided into generations. The first generation, led by figures like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, established the foundational principles, emphasizing detailed observation combined with romantic or allegorical themes. Sonntag belongs more comfortably to the second generation, which flourished from the mid-century onwards and included artists such as Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, Sanford Robinson Gifford, and John Frederick Kensett.

These later artists often expanded the geographical scope, depicting the Rockies, South America, and the Arctic, and sometimes employed more dramatic effects of light and atmosphere, a tendency known as Luminism found in the work of Gifford and Kensett. Sonntag shared the second generation's interest in dramatic natural phenomena and expansive vistas, though his style retained a unique blend of American observation and European idealism.

Developing a Style: The American Wilderness

In his early career, Sonntag focused intensely on the American landscape, particularly the Appalachian regions accessible from Cincinnati. He undertook numerous sketching expeditions into the hills and valleys of Ohio, Kentucky, and West Virginia (then part of Virginia). These trips provided him with the raw material – sketches and studies from nature – that he would later transform into finished oil paintings in his studio.

His depictions of the American wilderness were characterized by a romantic sensibility. He was drawn to dramatic compositions, often featuring rugged mountains, deep valleys, cascading waterfalls, and turbulent skies. Unlike the meticulous detail found in some of his contemporaries like Church, Sonntag often employed a broader handling of paint and a heightened sense of atmosphere, emphasizing the emotional impact of the scene.

His work from this period often carries echoes of European romantic landscape traditions, perhaps influenced by prints or paintings he had seen. There's a tendency towards idealization, smoothing over the rougher aspects of nature to create harmonious, albeit sometimes theatrical, compositions. He frequently explored the themes of autumn, capturing the brilliant foliage of the American forests, and sunsets, using light and color to evoke powerful moods.

European Sojourns and Italian Influence

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons and refine his technique, Sonntag embarked on his first trip to Europe in 1853. This journey, followed by another in 1855-1856, proved highly influential. He spent a significant amount of time in Italy, particularly in Florence, the cradle of the Renaissance and a major center for expatriate artists.

The experience of Italy profoundly affected Sonntag's art. He was captivated by the historical resonance of the landscape, the classical ruins, and the quality of the Mediterranean light. While he continued to paint American scenes, his repertoire expanded to include idealized Italian landscapes. These works often featured picturesque elements like ancient temples, crumbling villas, stone pines, and serene lakes, bathed in a warm, golden light reminiscent of masters like Claude Lorrain.

This European influence manifested not only in his Italian subjects but also subtly informed his American landscapes. His compositions sometimes took on a more structured, classical balance, and his approach to light and atmosphere gained sophistication. The idealized, almost Arcadian quality seen in some of his Italian views occasionally permeated his depictions of the American wilderness, creating a unique fusion of Old World aesthetics and New World subject matter. He sought a poetic truth rather than strict topographical accuracy.

New York and National Recognition

Around 1857, seeking a larger stage and greater access to patrons and exhibition venues, Sonntag relocated to New York City, which had by then surpassed Philadelphia and Boston as the undisputed center of the American art world. This move marked a significant step in his career, placing him at the heart of the Hudson River School's network.

He quickly established himself within the New York art scene. In 1860, he was elected an Associate Member of the prestigious National Academy of Design (NAD), followed by full Academician status in 1861. The NAD was the premier art institution in the country, and membership conferred significant prestige. Sonntag became a regular exhibitor at the Academy's annual exhibitions, showcasing his work there for nearly four decades.

The 1860s and 1870s are generally considered the peak of Sonntag's career and popularity. He continued to travel and sketch, finding inspiration in the mountain scenery of the Alleghenies, the Shenandoah Valley, the Catskills, and the Adirondacks in New York, as well as parts of New England. His paintings were sought after by collectors and praised for their evocative beauty and technical skill. He exhibited widely beyond the NAD, including venues like the Boston Athenaeum, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia, and the Brooklyn Art Association.

Collaboration and Contemporaries

Sonntag's career involved notable interactions and collaborations with fellow artists. His relationship with Robert S. Duncanson, whom he knew from his Cincinnati days, is particularly significant. Duncanson, an African American painter who achieved international recognition, occasionally collaborated with Sonntag. While the exact nature and extent of their joint work are debated by scholars, their association highlights the interconnectedness of the mid-century art world.

In Cincinnati, Sonntag had also reportedly collaborated with John C. Wolfe on large-scale moving panoramas, popular forms of entertainment at the time, depicting themes like Milton's Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained. This experience with large formats and dramatic narratives may have influenced his easel painting. He was also associated with John R. Robinson in Cincinnati.

In New York, he was part of a vibrant community of landscape painters. He exhibited alongside fellow Hudson River School artists like Sanford Robinson Gifford, John Frederick Kensett, Jervis McEntee, and Jasper Francis Cropsey at the National Academy. He also knew Worthington Whittredge, his former Cincinnati colleague, who had also established a successful career in the East. While part of this community, Sonntag maintained his distinct stylistic identity.

His relationship with the critical establishment was sometimes mixed. While generally well-regarded, some critics occasionally found fault with what they perceived as excessive "expressiveness" or a lack of finish in his work. Comments sometimes pointed to his bold color contrasts, relatively loose brushwork in certain passages, or thick application of paint (impasto), which deviated from the smoother, more detailed finish favored by some academic tastes of the time.

Themes and Subjects

Sonntag's oeuvre revolved primarily around landscape, explored through various motifs and moods. Mountain scenery was a recurring theme, capturing the grandeur and majesty of the American ranges he visited. His paintings often depict specific locations, such as the Adirondacks or the Shenandoah Valley, but filtered through his romantic and idealizing lens.

Water, in the form of rivers, lakes, and waterfalls, was another favorite subject, allowing him to explore reflections, movement, and the interplay of light. Sunsets and sunrises provided opportunities for dramatic color effects and atmospheric depth, imbuing his landscapes with emotional resonance. Autumn, with its vibrant foliage, was a season he returned to frequently, exemplified by works like his often-titled Autumn Landscape.

His time in Italy yielded numerous paintings of classical ruins set in picturesque landscapes, appealing to the era's taste for the romantic past. Works like View of Harpers Ferry, Virginia demonstrate his ability to capture specific American locales, though often imbued with a sense of timelessness or historical reflection.

A particularly interesting aspect of his work relates to the American Civil War. During and after the conflict, Sonntag painted landscapes set in Virginia, a major theater of the war. While not depicting battles directly, these works, often serene yet subtly melancholic, are interpreted by some scholars as reflections on the war, memory, and the healing power of nature in a scarred landscape. His alleged Progress of Civilization series, likely related to Thomas Cole's famous cycles, would also point to an interest in broader historical or allegorical themes, though details on this series remain somewhat elusive.

Artistic Technique and Style

Sonntag's style is best characterized as Romantic Realism, blending observation of nature with subjective interpretation and idealization. He possessed a strong sense of composition, often using framing elements like trees or foreground rocks to lead the viewer's eye into the expansive vista beyond. Diagonals were frequently employed to create dynamic movement through the landscape.

His use of color was often bold and expressive, particularly in his depictions of sunsets and autumn foliage, where he employed rich reds, oranges, and yellows, sometimes contrasted with deep blues and purples in the shadows or sky. He was adept at capturing atmospheric perspective, rendering distant mountains in hazy blues and grays to convey a sense of depth and scale.

While capable of rendering detail, Sonntag's brushwork could be varied. In some areas, particularly foreground elements, it might be relatively descriptive, while in others, such as skies or distant ranges, it could become broader and more suggestive, contributing to the overall mood and avoiding laborious detail. This variation, sometimes criticized as lacking "finish," can also be seen as a strength, lending vitality and expressiveness to his work. His Italian scenes often adopted a smoother finish and a warmer, more golden palette compared to the cooler tones sometimes found in his North American views.

Later Career and Legacy

William Louis Sonntag continued to paint and exhibit actively throughout the later decades of the nineteenth century, maintaining his studio in New York City. While his style remained largely consistent with the romantic landscape tradition he had mastered, the American art world began to change around him. The influence of the French Barbizon School, with its emphasis on intimate, tonal landscapes (popularized in America by artists like George Inness), and the rise of Impressionism began to shift tastes away from the grand, detailed, or idealized manner of the Hudson River School.

While Sonntag remained respected, his work may have seemed somewhat conservative compared to these newer trends towards the end of his life. He continued to exhibit at the National Academy of Design and other venues, but the peak of his widespread popularity had likely passed by the 1880s or 1890s.

He died in New York City on January 22, 1900, at the age of 77. Like many Hudson River School painters, his reputation experienced a decline in the early twentieth century as modernism took hold. However, a revival of interest in nineteenth-century American art began in the mid-twentieth century. Exhibitions, such as those held by galleries like Vose Galleries of Boston, played a role in reintroducing Sonntag and his contemporaries to scholars, collectors, and the public.

Today, William Louis Sonntag is recognized as a talented and prolific contributor to the Hudson River School tradition. His paintings are held in the collections of major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art (which absorbed the Corcoran Gallery collection), the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and numerous regional museums and university galleries like the Peabody Institute at Johns Hopkins University. His work is valued for its technical skill, its evocative portrayal of both American and Italian scenery, and its embodiment of nineteenth-century romantic landscape ideals.

Conclusion

William Louis Sonntag Sr. navigated the American art world for over half a century, leaving behind a substantial body of work that captures the spirit of his time. From his determined beginnings in Cincinnati to his established position within the New York art scene and the National Academy of Design, he remained dedicated to the art of landscape painting. As a key figure in the second generation of the Hudson River School, he celebrated the beauty and grandeur of the American continent while also drawing inspiration from the classical landscapes of Italy. His paintings, characterized by dramatic compositions, rich color, and a blend of observation and romantic idealization, continue to resonate with viewers, offering compelling visions of nature as seen through the eyes of a nineteenth-century American master. His collaborations, travels, and consistent presence in major exhibitions underscore his active participation in the artistic life of his era.