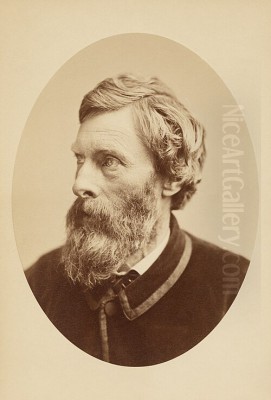

Jasper Francis Cropsey stands as a pivotal figure in the narrative of nineteenth-century American art. Born into a rapidly changing nation finding its cultural identity, Cropsey became intrinsically linked with the Hudson River School, the country's first major homegrown art movement. While trained initially as an architect, his passion gravitated towards the canvas, where he translated the American landscape, particularly the vibrant hues of autumn, into idealized yet meticulously observed visions. His long and productive career bridged the gap between meticulous realism and romantic sensibility, leaving behind a legacy of luminous landscapes that continue to captivate viewers with their celebration of nature's grandeur.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings

Jasper Francis Cropsey entered the world on February 18, 1823, on his family's farm in Rossville, Staten Island, New York. As the eldest of Jacob Rezeau Cropsey and Elizabeth Hilyer Cortelyou's eight children, his early years were marked by frequent illness. This recurring poor health, however, inadvertently steered him towards artistic pursuits. Confined indoors for extended periods, the young Cropsey taught himself to draw, filling notebooks with sketches of the world around him. His fascination extended beyond simple representation; he developed a keen interest in architecture, meticulously crafting detailed models of buildings out of wood and other materials.

This early aptitude for design did not go unnoticed. At the tender age of thirteen, one of his intricate model houses earned him a diploma and first prize from the Mechanics' Institute of the City of New York in 1837. This recognition likely bolstered his confidence and pointed towards a potential career path. While his formal schooling was intermittent due to his health, his innate talent and dedication to self-study laid a crucial foundation for his future endeavors in both architecture and painting. The landscapes of Staten Island and the nearby Hudson River Valley undoubtedly imprinted themselves on his young mind, providing the raw material for his later artistic explorations.

Architectural Foundations and the Turn to Painting

Following his early success with architectural models, Cropsey pursued formal training in the field. He apprenticed for five years under the New York architect Joseph Trench. This period provided him with invaluable technical skills in drafting, perspective, and structural understanding – knowledge that would subtly inform his landscape compositions throughout his career. He established his own architectural office in New York City in 1843, demonstrating a serious commitment to the profession. Early projects included designs for private residences and even contributions to ecclesiastical architecture, such as the design for the towers of the St. John's Episcopal Church in Yonkers, New York.

However, the allure of painting, particularly landscape painting, grew increasingly strong. Encouraged by Trench, who recognized his talent with watercolors, Cropsey began to dedicate more time to this pursuit. He started exhibiting his landscape paintings, initially watercolors, at the National Academy of Design in 1843, the same year he opened his architectural practice. His work quickly gained recognition within the New York art community. He was elected an associate member of the National Academy in 1844 and achieved the prestigious status of full Academician in 1851, cementing his place among the leading artists of his day. While he never entirely abandoned architecture, painting became his primary focus, offering a more profound medium for expressing his connection to the natural world.

The Hudson River School Context

Cropsey's rise as a painter coincided with the flourishing of the Hudson River School, America's first coherent school of landscape painting. This movement, largely inspired by the pioneering work of Thomas Cole, sought to capture the unique beauty and spiritual significance of the American wilderness. It wasn't a formal institution but rather a collective of artists united by a shared philosophy and subject matter, primarily the landscapes of the Hudson River Valley, the Catskill Mountains, the Adirondacks, and later, the White Mountains of New Hampshire and even more distant locales.

These artists, including figures like Asher B. Durand, Frederic Edwin Church (Cole's only formal pupil), John Frederick Kensett, and Sanford Robinson Gifford, viewed the American landscape as a source of national pride and divine revelation. Influenced by European Romanticism and the writings of American Transcendentalists like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, they saw nature as a manifestation of God's presence. Their paintings often combined detailed realism, based on careful outdoor sketching (plein air studies), with a sense of the sublime – awe mixed with a hint of terror before the vastness and power of nature. Compositionally, they often employed panoramic views, dramatic light effects (particularly sunrises and sunsets), and meticulous attention to botanical and geological detail.

Cropsey is typically associated with the second generation of Hudson River School painters. While deeply influenced by Cole's allegorical landscapes and Durand's emphasis on faithful naturalism, Cropsey developed his own distinct voice within the movement. His architectural training perhaps lent his compositions a certain structural clarity, while his unique sensitivity to color set him apart, particularly in his celebrated depictions of autumn. He embraced the core tenets of the school – the celebration of American nature, the blend of realism and idealism, and the search for spiritual meaning in the landscape.

European Sojourn and Broadened Horizons

In 1847, Cropsey married Maria Cooley. Shortly after their marriage, the couple embarked on an extended trip to Europe, a common practice for ambitious American artists seeking to immerse themselves in the masterpieces of the Old World and gain credibility. They traveled through England and France before settling in Italy for nearly two years, primarily residing in Rome from 1847 to 1849. This period proved immensely formative for Cropsey's artistic development.

In Rome, he occupied the former studio space of the recently deceased Thomas Cole, a symbolic inheritance that underscored his connection to the Hudson River School's founder. He sketched the Italian countryside, studied classical ruins, and absorbed the light and atmosphere of the Mediterranean landscape. He interacted with other American and European artists, broadening his artistic circle and exposing him to different styles and perspectives. While in Europe, he continued to paint and send works back to the United States for exhibition, maintaining his presence in the American art scene.

His time abroad, particularly in Italy, refined his technique and expanded his thematic range. While he remained committed to depicting American scenery, the European experience likely enhanced his understanding of composition, light, and atmospheric effects, drawing inspiration from masters like Claude Lorrain. He also spent time in London, where he would later return, engaging with the British art world and the works of painters like J.M.W. Turner, whose dramatic use of light and color may have resonated with Cropsey's own inclinations. This European sojourn equipped him with greater technical facility and a broader artistic context upon his return to the United States in 1849.

The Painter of Autumn

Upon returning to America, Cropsey increasingly focused on the subject that would define his popular reputation: the American autumn. While many Hudson River School artists depicted the fall landscape, Cropsey became uniquely associated with its fiery splendor. He earned the informal title "America's Painter of Autumn" for his ability to capture the season's intense and varied palette with unparalleled vibrancy. His autumn landscapes were not merely topographical records; they were celebrations of a uniquely American phenomenon, imbued with nationalistic and spiritual overtones.

Cropsey employed a high-keyed palette, utilizing brilliant reds, oranges, yellows, and golds to depict the turning foliage. He meticulously rendered the specific details of various tree species – maples, oaks, birches – capturing their distinct autumnal colors and forms. Works like Autumn on the Hudson River (1860) became iconic representations of the season, showcasing panoramic vistas bathed in the warm, hazy light characteristic of Indian summer. These paintings resonated deeply with the public and critics, who saw in them a reflection of America's natural bounty and unique identity.

His bold use of color occasionally drew criticism. The influential English art critic John Ruskin, a champion of detailed naturalism, reportedly found Cropsey's colors exaggerated during the artist's later stay in London (1856-1863). According to anecdote, Cropsey defended his palette by gathering actual autumn leaves from American forests and presenting them to Ruskin and the Royal Academy to demonstrate the veracity of his painted hues. Whether apocryphal or not, the story highlights Cropsey's commitment to capturing the specific, intense coloration of the American fall, distinguishing it from the more muted tones often found in European landscapes. His autumn scenes became synonymous with his name, representing a peak of his artistic achievement and contribution to the Hudson River School aesthetic.

Masterworks and Signature Style

Cropsey's oeuvre is rich with iconic landscapes that exemplify his mature style. Autumn on the Hudson River (1860), painted during his time in London and exhibited to great acclaim, is perhaps his most famous work. This expansive panorama captures a wide sweep of the river valley under a luminous, late-afternoon sky. The foreground is alive with meticulously detailed autumn foliage in brilliant hues, while the distant hills recede into a soft, atmospheric haze. The painting masterfully balances detailed observation with an idealized, almost elegiac mood, embodying the Hudson River School's blend of realism and romanticism.

Another significant work, Greenwood Lake (1874), depicts a favorite sketching ground for the artist near the New York-New Jersey border. This painting showcases his skill in rendering tranquil water reflections and the lush greenery of summer, demonstrating his versatility beyond autumn scenes. Summer, Lake Ontario (1857) captures a serene, almost dreamlike evening atmosphere, highlighting his sensitivity to light and mood. His depiction of Niagara Falls (1857) tackles one of the great natural wonders of North America, emphasizing its sublime power and grandeur, a theme popular among his contemporaries like Frederic Edwin Church.

Cropsey's architectural background often subtly influenced his compositions. There's frequently a sense of underlying structure and order, even in his most seemingly wild landscapes. He skillfully used framing elements like trees or foreground rocks to lead the viewer's eye into the scene. His handling of light is masterful, creating depth and defining form, often employing the soft, diffused light associated with Luminism, a related tendency within American landscape painting also practiced by artists like John Frederick Kensett and Martin Johnson Heade. Works like The High Bridge (c. 1849-50) directly integrate man-made structures into the landscape, exploring the relationship between nature and human intervention, while The Blasted Tree (1850) uses a dramatic natural event to evoke themes of resilience and the cycle of life and death.

Later Career: Symbolism, Watercolor, and Challenges

In the later decades of his career, Cropsey's thematic interests sometimes shifted towards more overtly symbolic and allegorical subjects, echoing the earlier work of Thomas Cole. He undertook ambitious projects like The Spirit of War (1851) and The Spirit of Peace (1851), large canvases exploring contrasting themes through landscape. His deep religious faith also found expression in his art. He created works inspired by John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress, visualizing the allegorical journey through idealized landscapes imbued with Christian symbolism. The series The Four Seasons (completed later in his career) allowed him to explore the cyclical nature of life and the divine order manifested in the changing landscape.

Cropsey was also a skilled watercolorist throughout his career. Recognizing the potential of this medium, he joined with ten other artists, including Samuel Colman and William Trost Richards, to found the American Society of Painters in Water Colors (now the American Watercolor Society) in 1866. This demonstrated his commitment to promoting diverse artistic practices and his proficiency beyond oil painting. His watercolors often possess a freshness and immediacy, serving both as studies for larger oils and as finished works in their own right.

Despite his artistic successes, Cropsey faced significant financial challenges later in life. The popularity of the Hudson River School began to wane in the 1870s and 1880s, supplanted by newer styles influenced by the Barbizon School and Impressionism, championed by artists like George Inness. Patronage shifted, and Cropsey, like many of his contemporaries, found it increasingly difficult to sell his large-scale landscapes. In 1884, facing foreclosure, he was forced to sell his beloved home and studio, "Aladdin," in Warwick, New York. He subsequently moved to Hastings-on-Hudson, New York, building a more modest home he named "Ever Rest." Personal tragedy also struck when his daughter Rose and her husband were killed in a train accident. Despite these hardships, Cropsey continued to paint and exhibit, adapting his style somewhat but remaining largely true to his landscape roots until his death on June 22, 1900, in Hastings-on-Hudson.

Legacy and Rediscovery

Although Jasper Cropsey's fame diminished in the later years of his life and the early twentieth century as artistic tastes changed, his reputation experienced a significant revival beginning in the mid-twentieth century. This coincided with a broader scholarly and public rediscovery of the Hudson River School. Art historians and curators began to re-evaluate the contributions of Cropsey and his contemporaries, recognizing the artistic merit and cultural significance of their work. His paintings, once considered old-fashioned, were again celebrated for their technical skill, evocative beauty, and unique expression of the American spirit.

Today, Cropsey is firmly established as a major figure in American art history. His works are held in the permanent collections of virtually every major American museum, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. His paintings, particularly the vibrant autumn landscapes, remain highly sought after by collectors and beloved by the public. His home and studio, "Ever Rest" in Hastings-on-Hudson, has been preserved and is now the site of the Newington-Cropsey Foundation, dedicated to preserving his legacy and promoting the study of nineteenth-century American art. His daughter, Lily Cropsey, also became an artist, carrying on the family's creative tradition.

Cropsey's enduring legacy lies in his masterful ability to capture the specific character of the American landscape, especially its autumnal glory. He successfully blended detailed observation with romantic idealism, creating images that were both topographically recognizable and spiritually resonant. His background in architecture lent a unique structural integrity to his compositions, while his unparalleled command of color brought the American landscape to life with unprecedented vibrancy. He stands alongside Cole, Durand, Church, and Bierstadt as a defining artist of the Hudson River School, leaving behind a rich visual record of nineteenth-century America's relationship with its natural environment.

Conclusion

Jasper Francis Cropsey's journey from an architect's apprentice to one of America's most celebrated landscape painters charts a course through the heart of nineteenth-century American culture. As a key member of the Hudson River School's second generation, he absorbed the influences of pioneers like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand while forging his own distinct path. His unique sensitivity to color, particularly the brilliant hues of autumn, earned him lasting fame and defined a significant aspect of the school's aesthetic. His paintings, whether depicting the fiery foliage of the Hudson Valley, the tranquil waters of Greenwood Lake, or the allegorical landscapes of the soul, consistently reveal a deep reverence for nature combined with masterful technical skill. Though challenged by shifting tastes and financial hardship later in life, Cropsey's art endured, experiencing a well-deserved rediscovery that secured his place as a vital contributor to the story of American art – an architect of sublime landscapes and the undisputed painter of American autumn.