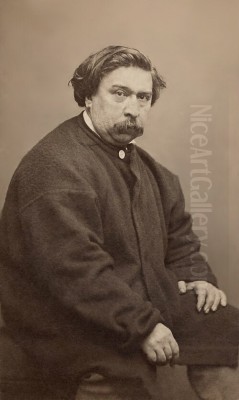

Thomas Couture stands as a significant yet complex figure in the landscape of 19th-century French art. Born during a period of immense social and artistic change, he navigated the currents between established academic traditions and emerging modern sensibilities. Primarily known as a history painter, Couture achieved considerable fame with his monumental canvases, most notably "The Romans of the Decadence." However, his influence extended far beyond his own artistic output; his independent atelier became a crucial training ground for a generation of artists who would go on to redefine painting, including the revolutionary Édouard Manet. Couture's career was marked by both official success and profound disillusionment, embodying the tensions of an era grappling with its relationship to the past and the definition of modernity.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Thomas Couture was born on December 21, 1815, in Senlis, Oise, France. Seeking greater opportunities, his family moved to Paris when he was young, setting the stage for his artistic education in the heart of the French art world. He initially enrolled at the École des Arts et Métiers, a school focused on industrial arts, before transitioning to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the bastion of academic training.

At the École des Beaux-Arts, Couture had the privilege of studying under two prominent masters of the time: Antoine-Jean Gros and Paul Delaroche. Gros, a pupil of Jacques-Louis David, was renowned for his large-scale historical paintings, particularly those glorifying the Napoleonic era, though his later career saw a stylistic shift. Delaroche, known for his meticulously rendered historical scenes often tinged with melodrama, represented a popular, albeit less revolutionary, form of academic history painting. Studying under these figures provided Couture with a solid foundation in academic techniques, composition, and the grand tradition of history painting.

Despite his training, Couture's early career was not without its struggles. He repeatedly attempted to win the coveted Prix de Rome, a prestigious scholarship awarded by the Académie des Beaux-Arts that allowed winners to study in Rome. Successive failures frustrated Couture, who reportedly felt the fault lay with the institution rather than his own abilities. His perseverance eventually paid off in 1837 when he was awarded the second prize. While not the top honor, this recognition significantly boosted his reputation and marked a turning point in his burgeoning career.

The Rise to Fame: 'The Romans of the Decadence'

The defining moment of Couture's career arrived with the Paris Salon of 1847. It was here that he exhibited his monumental painting, "Les Romains de la décadence" (The Romans of the Decadence). The work was an immediate sensation, catapulting Couture to the forefront of the French art scene. Measuring nearly five by eight meters, the canvas depicted a sprawling, orgiastic scene set within a grand classical hall, illustrating the moral decay and lassitude of the late Roman Empire.

The painting was widely praised for its technical brilliance, complex composition involving numerous figures, and ambitious scale. Critics admired Couture's skillful handling of anatomy, drapery, and architectural detail, which demonstrated his mastery of academic principles learned under Gros and Delaroche. The work's vibrant color and dynamic arrangement of figures also drew positive commentary. Its composition, featuring a central void and figures arranged in frieze-like groups, consciously echoed grand compositions of the past, with some critics noting a dialogue with Raphael's "The School of Athens," albeit presenting a scene of dissipation rather than intellectual pursuit.

However, "The Romans of the Decadence" was not without its detractors. While lauded for its technical execution, its subject matter provoked considerable debate. The painting was widely interpreted as an allegory for the perceived moral corruption and decadence of contemporary French society, particularly the wealthy bourgeoisie during the July Monarchy (1830-1848). This critical undertone, depicting excess and ennui, resonated with anxieties about social decay but also drew criticism for its perceived sensationalism or moral ambiguity. Some found the scene overly theatrical or the historical interpretation questionable. The controversy surrounding its meaning only added to its fame.

Despite the mixed critical reception regarding its message, the painting secured Couture's reputation. It was purchased by the state and eventually found its permanent home in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, where it remains one of the iconic works of 19th-century French academic painting. It cemented Couture's status as a leading history painter, capable of tackling grand themes with technical virtuosity, even as it hinted at a critical perspective that set him apart from more conservative academicians. The work exemplified his ability to synthesize classical forms with a more modern, critical sensibility.

Couture the Teacher: A Crucible of Talent

Following the success of "The Romans of the Decadence," Couture capitalized on his fame by opening an independent teaching studio in Paris in the 1840s. This atelier quickly became one of the most sought-after places for aspiring artists, attracting students from France and abroad. Couture's approach to teaching was distinct from the rigid, step-by-step methods often employed at the official École des Beaux-Arts.

While grounded in academic principles, Couture encouraged his students to develop their individual styles and to look beyond mere imitation of classical models or the works of their master. He placed a strong emphasis on direct observation, urging students to learn from life and nature. This included studying the live model, but also potentially engaging with the world outside the studio, a departure from the purely studio-based exercises common in academic training. He stressed the importance of capturing the initial impression and maintaining freshness in execution.

His technical instruction focused on sound drawing and construction but also gave significant weight to painterly qualities – the handling of paint, the use of color, and the importance of the ébauche (the initial painted sketch or underpainting). He believed the vitality of the first lay-in should be preserved in the final work, a concept that contrasted with the highly finished, polished surfaces often favored by the Academy. This emphasis on technique and individual expression proved highly influential.

Couture's studio nurtured an impressive roster of artists who would achieve significant recognition. The most famous among them was Édouard Manet, who studied with Couture for six years (circa 1850-1856). While Manet absorbed Couture's technical lessons, particularly regarding the ébauche and bold brushwork, he ultimately rebelled against his master's historical subjects and somewhat theatrical style. Their relationship was reportedly complex and sometimes strained, with Couture criticizing Manet's developing modern approach. Nevertheless, Couture's studio provided Manet with essential training and a space to begin forging his own path, becoming a pivotal figure bridging Realism and Impressionism.

Other notable students included Henri Fantin-Latour, known for his sensitive portraits and still lifes, and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, who became a leading figure in Symbolist mural painting. The American painter John La Farge also passed through Couture's studio, as did, according to some accounts, Edgar Degas, though his time there might have been brief. The provided source material also lists Claude Monet as a student, although Monet's primary training is more strongly associated with artists like Eugène Boudin, Johan Barthold Jongkind, and the studio of Charles Gleyre. If Monet did study with Couture, it was likely not his formative experience. German artists like Anselm Feuerbach and Wilhelm Leibl also benefited from Couture's instruction. Couture's teaching, therefore, played a crucial role in shaping a diverse group of artists who would contribute significantly to various artistic movements in the latter half of the 19th century.

Artistic Style and Philosophy: Bridging Traditions

Thomas Couture's artistic style is often characterized as "Eclecticism." This term reflects his position between the dominant artistic currents of his time: Neoclassicism, with its emphasis on line, form, and historical subject matter derived from antiquity, and Romanticism, which prioritized color, emotion, and often dramatic or exotic themes. Couture sought to synthesize elements from both traditions, along with influences from Old Masters like the Venetians (Titian, Veronese) and Flemish painters (Rubens), known for their rich color and dynamic compositions.

He adhered to the academic hierarchy of genres, prioritizing history painting, but infused his historical scenes with a dynamism and painterly quality often associated with Romanticism. His compositions, while carefully structured, often featured energetic brushwork and a sensitivity to light and color that went beyond strict Neoclassical linearity. He believed in the importance of facture – the visible handling of paint – allowing the process of creation to remain evident in the final work.

Couture articulated his artistic philosophy and teaching methods in his book, "Méthode et entretiens d'atelier" (Method and Workshop Conversations), published in 1867. In this work, he criticized the overly rigid and formulaic aspects of academic training at the École des Beaux-Arts. He argued against the excessive focus on copying plaster casts and antique sculptures at the expense of studying life and developing painterly skills. He advocated for a balance between drawing and painting, elevating the importance of color and brushwork alongside linear construction.

His book championed the idea of grounding art in the observation of reality while still aiming for idealized or historically significant subjects. He encouraged artists to find inspiration in the great masters of the past but warned against slavish imitation. Instead, he urged them to adapt historical lessons to contemporary expression. This eclectic approach, while sometimes criticized for lacking a single, unified vision, allowed Couture to create works that appealed to official tastes while subtly challenging academic norms. His emphasis on technique and the importance of the initial sketch resonated with younger artists seeking alternatives to strict academic finish.

Other Notable Works

While "The Romans of the Decadence" remains his most famous painting, Thomas Couture produced a diverse body of work throughout his career, encompassing history painting, allegory, portraiture, and genre scenes. These works further illustrate his stylistic range and thematic concerns.

One significant commission was "L’Enrôlement des Volontaires de 1792" (The Enrollment of the Volunteers of 1792), begun in 1848. This massive, unfinished canvas (now housed in the Musée des Beaux-Arts d'Orléans) depicted the patriotic fervor of the French Revolution. Intended as a major public work, its grand scale and historical theme were typical of Couture's ambitions. However, like several of his large public commissions, it faced difficulties and was never fully completed, perhaps reflecting the political instability of the time or Couture's own struggles with sustained large-scale projects.

Another important official work was "Le Baptême du Prince Impérial" (The Baptism of the Prince Imperial), commemorating the christening of Napoleon III's son in 1856. Housed in the Musée National du Château de Versailles, this large painting showcases Couture's ability to handle complex group portraiture and ceremonial occasions, though it perhaps lacks the critical edge of "The Romans."

Couture also explored allegorical themes, often with a moralizing tone similar to "The Romans." "L'Amour de l'or" (The Love of Gold), for instance, critiques greed and materialism. "La Courtisane moderne" or "Le Char de la Courtisane" (The Modern Courtesan or The Courtesan's Chariot) presents another commentary on contemporary morals, depicting a triumphant courtesan pulled in a chariot, a modern parallel to the decadence explored in his Roman scene.

Beyond these grand subjects, Couture was a skilled portraitist, capturing likenesses with sensitivity and often employing the looser, more painterly style evident in his smaller works. "Portrait of a Young Woman, Seated" (c. 1850-55) exemplifies his ability in this genre. He also painted genre scenes, sometimes depicting figures from the commedia dell'arte, like "Pierrot malade" (Sick Pierrot) or "La Pâmoison de Pierrot" (Pierrot Fainting), sometimes translated as "Pierrot's Drunkenness," which blend theatricality with psychological observation. Works like "Se Rendant à l'Audience" (Going to the Audience, or Lawyer Pleading His Case) and "A Zouave" show his interest in contemporary character types and everyday life, albeit rendered with his characteristic technical polish. These smaller, often more intimate works were frequently praised for their freshness and spontaneity.

Controversies and Later Years

Despite his initial success and influential teaching career, Thomas Couture's later life was marked by increasing disillusionment and withdrawal from the official art world. Several factors contributed to this shift. His relationship with the art establishment became strained due to difficulties with major public commissions.

In the late 1840s and 1850s, Couture received prestigious commissions for large-scale mural paintings for Parisian churches, such as Saint-Eustache and Sainte-Clotilde. However, these projects became mired in delays, disputes, and criticisms. He ultimately failed to complete the first two commissions, and the third received a mixed reception. These setbacks were deeply frustrating for Couture and likely damaged his standing with official patrons. He felt misunderstood and unsupported by the bureaucracy and critics.

His outspoken criticism of the academic system, culminating in his 1867 book "Méthode et entretiens d'atelier," further alienated him from parts of the art establishment. While his teaching methods were popular with students seeking alternatives, his public critiques were not always welcomed by those in power at the Academy or the Ministry of Fine Arts.

The political turmoil of the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) and the subsequent Paris Commune likely contributed to his decision to leave the capital. Seeking refuge from the upheavals and perhaps disillusioned with the direction of both art and politics, Couture retreated to his country house in Villiers-le-Bel, north of Paris.

In his later years, he lived in relative seclusion, continuing to paint but largely detached from the Parisian art scene he had once dominated. This withdrawal reflected his independent spirit and perhaps a sense of bitterness towards an art world he felt had failed to fully appreciate his vision or accommodate his sometimes difficult personality. Thomas Couture died in Villiers-le-Bel on March 30, 1879. He was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, the final resting place of many prominent figures in French arts and letters.

Couture and His Contemporaries

Thomas Couture occupied a unique position relative to the major artistic figures and movements of his time. He was a contemporary of both the leading Romantic painter, Eugène Delacroix, and the champion of Realism, Gustave Courbet, yet his work charted a different course.

While Couture admired aspects of Romanticism, particularly its emphasis on color and expressive brushwork, he maintained a stronger connection to classical structure and historical themes than Delacroix. There are no records of significant direct interaction between Couture and Delacroix, but Couture's students, notably Manet, deeply admired Delacroix's work, creating an indirect link. Couture's style, attempting to blend classical form with romantic sensibility, can be seen as a response to the artistic debates shaped by figures like Delacroix and the Neoclassical standard-bearer, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

Gustave Courbet represented a more radical departure from tradition. His commitment to depicting contemporary life and ordinary people, often on a scale previously reserved for history painting, challenged the academic hierarchy that Couture, despite his criticisms, still largely operated within. Courbet's Realism, exemplified by works like "The Stone Breakers" or "A Burial at Ornans," focused on the unvarnished truth of the present, whereas Couture often used historical or allegorical settings to comment on contemporary issues. Again, direct interaction records between Couture and Courbet are lacking. However, both artists courted controversy and challenged artistic conventions in their own ways. Couture's "Romans" caused a sensation in 1847, much as Courbet's works would in the 1850s. Both artists, in different manners, used large-scale canvases to make significant statements, pushing the boundaries of acceptable subject matter and style.

Couture's eclecticism placed him somewhat apart from these more clearly defined movements. He was neither a pure Neoclassicist nor a full-fledged Romantic, nor a Realist in the vein of Courbet. He represented a form of "juste milieu" (middle way) or perhaps a sophisticated academicism infused with modern sensibilities. This position made him influential as a teacher, offering a bridge between tradition and innovation, but perhaps also limited his appeal to those seeking more radical artistic statements.

Legacy and Influence

Thomas Couture's legacy in art history is multifaceted. He is remembered primarily for his masterpiece, "The Romans of the Decadence," a quintessential example of ambitious 19th-century French academic painting that captured the anxieties of its time through historical allegory. This work, along with his other history paintings and portraits, secured his place as a technically accomplished artist who navigated the complex stylistic landscape between Neoclassicism and Romanticism.

Perhaps his most enduring legacy lies in his role as a teacher. His independent atelier provided crucial training for a generation of artists who would go on to shape modern art. His emphasis on direct observation, painterly technique, and individual expression, even while grounded in academic fundamentals, offered a vital alternative to the stricter doctrines of the École des Beaux-Arts. His influence on Édouard Manet is particularly significant; although Manet ultimately broke away from Couture's style, the technical foundations and encouragement of a bolder approach to paint application learned in Couture's studio were formative. Through Manet and others, Couture's teaching indirectly impacted the development of Impressionism and subsequent modern movements.

His book, "Méthode et entretiens d'atelier," provides valuable insight into the artistic debates and pedagogical approaches of the mid-19th century. It stands as a testament to his critical engagement with the academic system and his efforts to reform artistic training by balancing tradition with a greater emphasis on painterly qualities and individual observation.

While his own eclectic style eventually fell out of favor as Impressionism and other avant-garde movements gained prominence, Thomas Couture remains a pivotal figure. He represents the complexities and contradictions of 19th-century art, an artist deeply rooted in tradition yet critical of its limitations, and a teacher whose influence extended far beyond his own aesthetic preferences, helping to nurture the talents that would ultimately revolutionize painting. His work continues to be studied for its technical mastery, its engagement with historical and social themes, and its place within the rich tapestry of French art.