Sir Frederick Grant Banting, a name indelibly etched in the annals of medical history for his co-discovery of insulin, harbored a profound and lifelong passion that extended far beyond the laboratory and lecture hall. While his scientific achievements rightfully earned him global acclaim, including the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1923, Banting also cultivated a significant, albeit less publicly heralded, identity as an artist. This exploration delves into the artistic life of this remarkable Canadian, tracing his development as a painter, his connections within the vibrant Canadian art scene of his time, and the unique perspective he brought to the canvas, shaped by both his scientific mind and his deep appreciation for the natural world.

Early Life and Nascent Artistic Stirrings

Born on November 14, 1891, on a farm in Alliston, Ontario, Frederick Banting's early life was steeped in the rural landscapes that would later feature prominently in his art. His initial inclinations were towards the arts, and childhood readings of illustrated books, such as "The Scout" and Arthur Conan Doyle’s "Sherlock Holmes" series, are said to have ignited this early spark. However, his academic path initially led him towards divinity at Victoria College, part of the University of Toronto. It wasn't long before his true calling in medicine emerged, and he transferred to the medical program.

Despite this shift, the artistic impulse remained. His academic performance in art at the collegiate level was reportedly not strong enough to pursue it as a primary university focus, which perhaps solidified his decision to commit to medicine. Yet, this did not extinguish his creative drive. The discipline and observational skills honed in his medical studies would, in subtle ways, inform his later artistic endeavors. Even during his formative years, the seeds of a dual passion were sown, one that would see him navigate the demanding worlds of scientific research and artistic expression.

The Great War and a Return to Art

The outbreak of World War I saw Banting enlist in the Canadian Army Medical Corps. He served with distinction on the Western Front in France, and his bravery during the Battle of Cambrai in 1918, where he continued to tend to wounded soldiers despite being wounded himself, earned him the Military Cross. His initial attempt to enlist was met with rejection due to poor eyesight, a hurdle he overcame on his second try. This wartime experience, with its profound intensity and exposure to human suffering, undoubtedly left an indelible mark on the young physician.

Upon his return to Canada and after a period establishing a medical practice, Banting's artistic inclinations resurfaced with renewed vigor. He initially engaged in woodcut art, a medium requiring precision and a strong sense of design. By the 1920s, as his medical career, particularly his groundbreaking research on insulin, began to take shape, he turned to watercolors. This medium, more fluid and spontaneous, reportedly served as a way to occupy his time while waiting for patients in his fledgling practice in London, Ontario, before his pivotal move to Toronto for full-time research. This period marked a more conscious engagement with visual art, a pursuit that offered a different kind of fulfillment from his scientific work.

The Toronto Arts and Letters Club: A Pivotal Encounter

A significant turning point in Banting's artistic journey occurred in 1925 when he joined the prestigious Arts and Letters Club of Toronto. This vibrant institution was a melting pot of creative minds – writers, musicians, architects, and, crucially for Banting, painters. It was here that he formed a close and enduring friendship with Alexander Young Jackson (A.Y. Jackson), a founding member of the renowned Group of Seven. Jackson, already an established and influential figure in Canadian art, became a mentor and a regular sketching companion to Banting.

The Arts and Letters Club provided Banting with an immersive environment where he could discuss art, share his work, and learn from seasoned professionals. Jackson, in particular, recognized Banting's genuine talent and passion. They shared a common experience, having both served on the Western Front during WWI, which may have forged an initial bond. More importantly, they shared a profound love for the Canadian wilderness and a desire to capture its unique character on canvas. This friendship would prove instrumental in shaping Banting's artistic development and would lead to numerous shared adventures in search of artistic inspiration.

The Influence of the Group of Seven

The Group of Seven, formally established in 1920, had revolutionized Canadian art. Its members, including A.Y. Jackson, Lawren Harris, J.E.H. MacDonald, Arthur Lismer, Franklin Carmichael, Frank Johnston (who later changed his name to Franz Johnston), and F.H. Varley, sought to create a distinctly Canadian school of landscape painting. They rejected the prevailing European academic traditions, venturing into the rugged, untamed wilderness of Canada to capture its raw beauty and unique spirit with bold colors, dynamic compositions, and a deeply personal vision. Tom Thomson, though he died before the Group's official formation, was a profound spiritual influence and close associate of many of its members, his work embodying the very essence of their artistic quest.

Banting was undoubtedly influenced by the Group's philosophy and artistic approach. Their emphasis on direct experience with nature, their bold stylization, and their nationalistic pride in the Canadian landscape resonated with his own sensibilities. Through his friendship with Jackson, Banting gained firsthand exposure to their techniques and ideals. He began to adopt a more robust and expressive style, moving beyond simple representation to imbue his landscapes with a sense of atmosphere and emotional depth. The Group's dedication to depicting the true north, strong and free, provided a powerful artistic framework within which Banting could develop his own voice. Other prominent members like Lawren Harris, with his increasingly abstract and spiritual depictions of the Arctic and mountain landscapes, and J.E.H. MacDonald, known for his rich portrayals of Algoma, would also have been part of the artistic milieu Banting was now connected to.

Sketching Expeditions: Banting and Jackson

The camaraderie between Banting and A.Y. Jackson extended beyond the confines of the Arts and Letters Club, leading to numerous sketching expeditions that spanned sixteen years, beginning around 1920. These trips took them to some of Canada's most iconic and challenging terrains. They explored the picturesque villages and dramatic coastline of the St. Lawrence River in Quebec, the rugged mining country around Cobalt in Northern Ontario, the majestic Rocky Mountains, and even the remote, stark beauty of the Canadian Arctic and the tundra near Yellowknife.

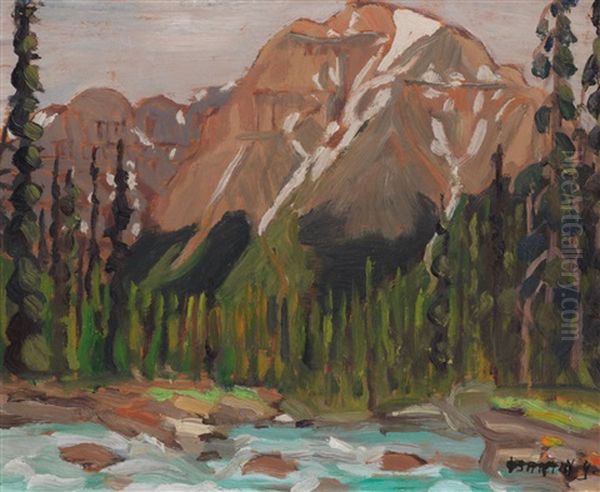

These expeditions were not mere leisure trips; they were serious artistic endeavors. Both artists would brave harsh weather conditions and difficult terrain, carrying their sketch boxes and supplies to capture the fleeting light and unique character of each location. Banting, primarily working with small wooden panels for his oil sketches, learned much from Jackson's experience in plein air painting. One of Banting's notable works, "Bic, Quebec" (1927), captures the charm of a Quebec village, likely reflecting the influence of Jackson's similar depictions of rural Quebec. Another significant piece, "In the Rocky Mountains," showcases his ability to convey the grandeur and imposing scale of Canada's western mountain ranges. These trips were vital for Banting, providing not only subject matter but also invaluable artistic guidance and a profound connection with the land.

Banting's Artistic Style and Themes

Frederick Banting's artistic output primarily consisted of landscapes, rendered in oil sketches on small panels and occasionally in watercolors. His style, while clearly influenced by A.Y. Jackson and the broader aesthetic of the Group of Seven, possessed its own distinct qualities. He demonstrated a keen eye for composition and a sensitive understanding of light and color, particularly in capturing the atmospheric effects of the Canadian seasons. His brushwork could be vigorous and expressive, conveying the raw energy of the wilderness, yet also capable of subtlety when depicting quieter, more intimate scenes.

His themes were quintessentially Canadian: the rolling hills of Southern Ontario, the quaint villages of Quebec, the vast expanses of the North, and the towering peaks of the Rockies. There was an honesty and directness in his work, a reflection of his genuine engagement with his subjects. He wasn't merely documenting scenery; he was interpreting it, conveying his emotional response to the landscapes that defined his homeland. His scientific training may have contributed to his meticulous observation of natural forms, but his artistic execution was driven by a more intuitive and emotional response to the beauty and power of nature.

The Scientist's Eye, The Artist's Hand

The duality of Banting's life as both a scientist and an artist presents a fascinating interplay. Did his scientific mind influence his artistic approach? It's plausible that the rigorous observational skills, the attention to detail, and the analytical thinking honed in the laboratory found an echo in his art. His understanding of anatomy and natural processes might have subtly informed his depiction of landscapes, giving them a sense of underlying structure and authenticity.

Conversely, did his artistic pursuits offer a necessary counterbalance to the intense intellectual demands of his scientific research? Art provided an outlet for creativity, intuition, and emotional expression that the objective world of science might not have fully accommodated. Sketching in the wilderness offered a respite, a way to connect with the world on a different, more sensory level. For Banting, art was not a mere hobby but a vital part of his being, a way to explore and express a different facet of his complex personality. He saw beauty in the natural world, whether through the lens of a microscope or the frame of a landscape, and sought to understand and convey it through both scientific inquiry and artistic creation.

Self-Doubt and Public Perception

Despite his evident talent and the encouragement he received from esteemed artists like A.Y. Jackson, Banting harbored a degree of self-doubt about his artistic abilities. He was acutely aware of his towering reputation as a scientist and Nobel laureate, and this sometimes made him hesitant to publicly exhibit his artwork. There was a concern, perhaps, that his artistic endeavors might not be taken seriously or, worse, that they might somehow detract from his scientific standing.

This internal conflict is not uncommon among individuals who excel in one field and pursue another with passion. The fear of being judged by a different set of standards, or of not meeting the high expectations associated with his name, likely weighed on him. Nevertheless, he did participate in some exhibitions, and his work was generally well-received within artistic circles. His friends in the art world recognized his genuine commitment and skill. For Banting, the act of painting itself, the process of observation and creation, was likely the primary reward, regardless of public acclaim.

Other Artistic Connections and Contemporaries

While A.Y. Jackson was his closest artistic confidant, Banting moved within a broader circle of Canadian artists. The Group of Seven's influence was pervasive, and Banting would have been familiar with the works of all its members. Lawren Harris, with his increasingly spiritual and abstracted landscapes of the North Shore of Lake Superior and the Arctic, was pushing Canadian art in new directions. J.E.H. MacDonald’s rich, decorative canvases of Algoma and the Rockies were highly influential. Arthur Lismer, known for his dynamic depictions of the Canadian wilderness and his significant contributions to art education, and F.H. Varley, a masterful portraitist who also painted expressive landscapes, were other key figures. Franklin Carmichael, the youngest original member, was celebrated for his watercolors and his depictions of the Ontario landscape.

Beyond the Group of Seven, other significant Canadian artists were active during Banting's time. Emily Carr, based on the West Coast, was creating powerful and deeply spiritual paintings of the forests and Indigenous cultures of British Columbia. Though her style and subject matter differed, she shared with the Group of Seven a commitment to forging a distinctly Canadian artistic identity. David Milne, another important contemporary, developed a highly personal and innovative style, often characterized by a delicate line and subtle color harmonies, capturing the essence of the Canadian landscape with a unique sensibility. While Banting's direct interactions with all these figures may varied, their collective efforts created the rich artistic environment in which he developed as a painter.

A Life Cut Short: Unfulfilled Artistic Aspirations

Tragically, Frederick Banting's life, and with it his artistic journey, was cut short. During World War II, he once again dedicated himself to serving his country, this time focusing on aviation medicine research for the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). He was instrumental in developing the G-suit, designed to prevent pilots from blacking out during high-speed maneuvers. It was on a mission related to this wartime work, en route to England to share his research with British counterparts, that he died. On February 21, 1941, the Lockheed Hudson bomber he was traveling in crashed in Newfoundland. Banting, then only 49 years old, succumbed to his injuries.

His untimely death was a profound loss not only to the world of medicine but also to the world of art. Banting had reportedly expressed a desire to dedicate himself more fully to painting after his retirement from scientific research. He had envisioned a future where he could devote more time to his canvases, to further explore the Canadian landscapes he loved, and to continue honing his artistic skills. This aspiration remained unfulfilled, leaving behind a body of work that, while significant, offers only a glimpse of what might have been. The promise of a mature artistic phase, enriched by a lifetime of experience and observation, was tragically curtailed.

Legacy: The Dual Heritage

Sir Frederick Banting is primarily remembered as a medical hero, the man whose discovery of insulin transformed diabetes from a fatal disease into a manageable condition, saving millions of lives. His contributions to science are monumental, and his name is rightly celebrated in medical institutions and research facilities worldwide. His birthplace and homestead in Alliston, Ontario, is preserved as Banting House National Historic Site of Canada, a testament to his scientific legacy.

However, to fully appreciate the man, one must also acknowledge his artistic endeavors. His paintings and sketches offer a different window into his soul, revealing a sensitivity, a love of nature, and a creative spirit that complemented his scientific genius. His art provides a more nuanced understanding of this complex individual, showing him not just as a brilliant researcher but also as a man who found solace, inspiration, and a unique form of expression in the act of painting. His artistic legacy, though overshadowed by his scientific fame, is an integral part of his story, enriching our understanding of one of Canada's most remarkable figures. The landscapes he painted remain as a testament to his passion, a visual diary of his journeys through the Canadian wilderness, and a reminder of the multifaceted nature of human talent.

Conclusion

Sir Frederick Grant Banting's life was a testament to the power of curiosity, dedication, and passion, expressed through both the rigorous discipline of science and the evocative language of art. While the world rightly honors him for the medical breakthrough that continues to impact countless lives, his artistic contributions offer a deeper, more personal insight into the man behind the legend. His landscape paintings, born from a genuine love for the Canadian wilderness and nurtured through his friendship with A.Y. Jackson and his connection to the Group of Seven, stand as a significant, if lesser-known, part of his legacy. They reveal a man who sought to understand and interpret the world around him not only through empirical investigation but also through the intuitive and emotional lens of an artist. In recognizing Banting the painter, we gain a more complete picture of a truly extraordinary Canadian, a figure whose dual pursuits in science and art continue to inspire.