John White Alexander (1856-1915) stands as a significant figure in American art at the turn of the twentieth century. A painter, illustrator, and muralist, he navigated the trans-Atlantic art world with grace, absorbing European influences while forging a distinctly personal style. Known primarily for his elegant and ethereal depictions of women, Alexander's work captured the refined sensibilities of the Gilded Age, blending elements of Realism, Impressionism, Art Nouveau, and Symbolism into a harmonious whole. His contributions extended beyond his canvases, as he became an influential arts administrator and a supporter of emerging talent, leaving an indelible mark on the American art scene.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, now part of Pittsburgh, on October 7, 1856, John White Alexander's early life was marked by hardship. He was orphaned at a young age, losing both parents, and was subsequently raised by his maternal grandparents. He received his early education in Pittsburgh, a burgeoning industrial city that offered limited artistic opportunities at the time. Despite these circumstances, Alexander's innate artistic talent began to surface early on.

His initial foray into the working world was as a telegraph boy at the Pacific and Atlantic Telegraph Co. in Pittsburgh. This position, however humble, proved to be a stepping stone. His drawings caught the attention of one of his superiors, Colonel Edward J. Allen, who recognized the young man's potential and became an early patron, providing encouragement and support. This encouragement was pivotal, leading Alexander to seek avenues where his artistic inclinations could be nurtured.

At the age of eighteen, around 1874, Alexander made the decisive move to New York City, the epicenter of American art and publishing. He secured a position at Harper's Weekly, one of the leading illustrated magazines of the era. Starting in the art department, he worked alongside prominent illustrators such as Edwin Austin Abbey, Charles Stanley Reinhart, and A. B. Frost. This environment provided invaluable practical training, honing his skills in draftsmanship and composition, and exposing him to the demands of visual storytelling for a mass audience. His work as an illustrator and political cartoonist for Harper's laid a solid foundation for his future career as a painter.

The European Crucible: Training and Influences

Like many aspiring American artists of his generation, Alexander understood that a European sojourn was essential for advanced artistic training and exposure to the masterpieces of the past and the innovations of the present. In 1877 or 1878, with savings accumulated from his illustration work, he embarked for Europe, initially intending to study in Paris.

Munich and the Academic Tradition

Alexander's plans shifted, and he first traveled to Munich, which at the time rivaled Paris as a center for art education. He enrolled at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, a prestigious institution known for its rigorous academic training. In Munich, he studied under artists such as Gyula Benczúr, a Hungarian history painter known for his academic precision and rich coloration. The Munich school emphasized strong draftsmanship, a dark, tonal palette, and bravura brushwork, often influenced by Old Masters like Frans Hals and Diego Velázquez.

During his time in Munich, Alexander became associated with a group of American artists, including Frank Duveneck and William Merritt Chase. Duveneck, a charismatic figure, had established a following of students, often referred to as the "Duveneck Boys," who admired his vigorous, direct painting style. Alexander spent time with this group in Polling, Bavaria, and later in Venice and Florence, absorbing their enthusiasm for painterly realism. The influence of this period can be seen in the robust handling and tonal qualities of his earlier works. Other artists he would have encountered or whose work was influential in these circles included John Henry Twachtman and J. Frank Currier.

The Whistlerian Touch

A pivotal encounter during Alexander's European years was with the expatriate American artist James McNeill Whistler. Alexander met Whistler in Venice, likely around 1879-1880, when Whistler was there creating his renowned series of etchings. Whistler's aesthetic philosophy, emphasizing "art for art's sake," tonal harmony, and the decorative arrangement of form and color, profoundly impacted Alexander. Whistler's sophisticated, often enigmatic portraits and his "Nocturnes" offered an alternative to both academic realism and burgeoning Impressionism.

Alexander absorbed Whistler's lessons on the subtle modulation of color, the importance of silhouette, and the creation of an evocative mood. This influence would become increasingly apparent in Alexander's mature style, particularly in his elegant, elongated figures and his preference for muted, harmonious color palettes. The refinement and decorative sensibility that characterize Alexander's best-known works owe a significant debt to Whistler's example.

Florence and Further Studies

After his time in Munich and Venice, Alexander also spent time in Florence, continuing to sketch, paint, and immerse himself in the art of the Italian Renaissance. The exposure to masters like Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci likely reinforced his appreciation for graceful line and harmonious composition. His European experience was not a monolithic indoctrination into one style but rather a period of absorption and synthesis, allowing him to gather diverse influences that he would later meld into his own unique artistic voice. He returned to the United States in 1881, well-equipped with technical skills and a broadened artistic perspective.

A Triumphant Return: Establishing a Career in America

Upon his return to New York City in 1881, John White Alexander quickly began to establish himself as a prominent figure in the American art world. His European training and refined sensibilities resonated with the tastes of the Gilded Age elite, and he soon found success, particularly as a portrait painter. He initially resumed some illustration work to support himself but increasingly focused on painting.

His portraits were sought after for their elegance, psychological insight, and sophisticated compositions. He painted many notable figures of the day, including writers, artists, and society personalities. Among his sitters were Oliver Wendell Holmes, Walt Whitman (though this portrait was more of a study), and the actress Maude Adams. His ability to capture not just a likeness but also the sitter's character and social standing made him a favored portraitist.

In 1887, Alexander married Elizabeth Alexander (née Alexander), a woman of social standing and literary connections, being the daughter of James Waddell Alexander, then president of the Equitable Life Assurance Society. This marriage further integrated him into New York's cultural and social elite, bringing him more portrait commissions and enhancing his visibility. Their son, James Waddell Alexander II, would later become a renowned mathematician.

The 1890s marked a period of significant international recognition for Alexander. He spent much of this decade in Paris, where his work was regularly exhibited at the prestigious Paris Salon. His paintings, particularly his evocative portrayals of women, garnered critical acclaim. He became a member of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris, a testament to his acceptance within the French art establishment. His success abroad solidified his reputation back in the United States.

The Alexander Style: Elegance, Line, and Light

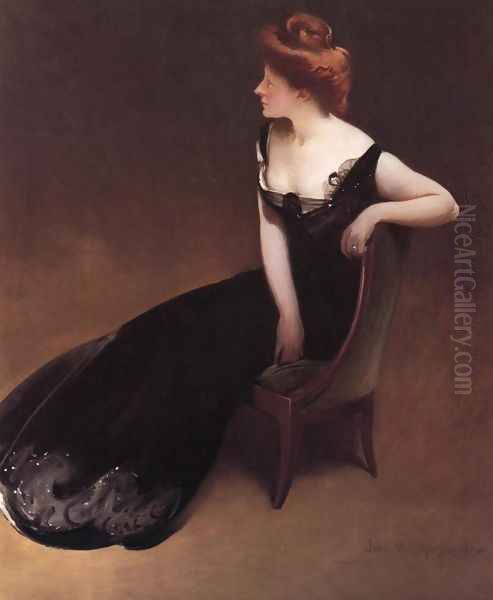

John White Alexander developed a distinctive artistic style characterized by its elegance, sinuous lines, and subtle handling of light and color. While he painted landscapes and still lifes, he is best known for his figural compositions, especially his idealized portraits of women.

The Female Form as Muse

Women were central to Alexander's artistic vision. He depicted them in graceful, often elongated poses, draped in flowing fabrics that accentuated the rhythmic curves of their bodies. His female figures are rarely specific individuals in his subject pictures; rather, they are archetypes of feminine grace, introspection, or quiet reverie. Works like Repose (1895) and The Green Bow (c. 1904) exemplify this focus. The figures often appear in dimly lit interiors, their forms emerging softly from the shadows, creating an atmosphere of intimacy and mystery.

His approach to the female form shows an affinity with Art Nouveau, with its emphasis on organic, flowing lines and decorative patterns. The sweeping curves of drapery, the elegant gestures, and the often-attenuated proportions of his figures align with the aesthetic ideals of this international movement, championed by artists like Alphonse Mucha and Gustav Klimt, though Alexander's interpretation was more restrained and less overtly ornamental.

Mastery of Color and Atmosphere

Alexander's palette was typically subdued and harmonious, often favoring muted greens, grays, blues, and ochres. He was a master of tonalism, carefully modulating values to create a sense of depth and atmosphere. Like Whistler, he understood the expressive power of color relationships and sought a unified, almost musical harmony in his compositions. His use of color was not merely descriptive but was integral to the mood and emotional impact of the painting.

He was particularly adept at rendering the effects of light, whether it was the soft glow of lamplight in an interior or the dappled sunlight in an outdoor scene. Works such as Sunlight (c. 1909) demonstrate his ability to capture the play of light and shadow with a sensitivity that suggests Impressionist influences, though his forms remained more solid and defined than those of staunch Impressionists like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro.

Innovative Techniques and Materials

Alexander often experimented with his materials and techniques. He frequently painted on coarse, absorbent canvas, which allowed the texture of the support to become an integral part of the final work. He applied his paint in thin layers, sometimes scrubbing it into the canvas, creating a matte surface that enhanced the ethereal quality of his images. This technique, combined with his fluid brushwork, contributed to the distinctive "look" of his paintings, which appeared both modern and timeless.

His compositions were carefully designed, often featuring strong diagonals, asymmetrical arrangements, and a focus on silhouette. He employed broad, sweeping brushstrokes that defined form and created a sense of movement, a technique that was both descriptive and decorative. This emphasis on design and pattern, combined with his elegant linearity, set his work apart from more academic or strictly realist painters of his time, such as Thomas Eakins or Winslow Homer, and aligned him more with the aesthetic concerns of artists like John Singer Sargent in his more decorative moments.

Signature Canvases: Portraits and Subject Pictures

Several of John White Alexander's paintings have become iconic representations of his style and the artistic currents of his era. These works showcase his mastery of portraiture and his ability to create evocative, symbolic subject pictures.

Repose (1895)

Perhaps one of his most famous works, Repose, now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, depicts a woman in a flowing white dress reclining on a dark green striped sofa. The composition is striking, with the sinuous lines of the figure and drapery creating a dynamic yet restful rhythm. The woman's face is partially obscured, adding to the sense of introspection and mystery. The limited palette and the interplay of light and shadow contribute to the painting's serene and dreamlike atmosphere. Repose was exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1895, where it received considerable acclaim, solidifying Alexander's international reputation. It embodies his characteristic elegance and his ability to infuse a seemingly simple scene with profound emotional resonance.

Isabella and the Pot of Basil (1897)

Inspired by John Keats's poem "Isabella, or the Pot of Basil," which itself is based on a tale from Boccaccio's Decameron, this painting is a powerful example of Alexander's engagement with Symbolist themes. The poem tells the tragic story of Isabella, whose lover is murdered by her brothers; she exhumes his head and buries it in a pot of basil, which she waters with her tears. Alexander's painting, housed in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, depicts Isabella in a dark, flowing gown, sensuously caressing a large pot of basil. Her pose is one of intense grief and devotion. The rich, dark colors and the dramatic lighting enhance the painting's emotional intensity. This work aligns Alexander with the Symbolist movement, which sought to express ideas and emotions through suggestive imagery rather than direct representation, a path also explored by European artists like Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes.

The Blue Bowl (1898)

Another celebrated work, The Blue Bowl, in the collection of the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, features a young woman in profile, delicately holding a blue porcelain bowl. The composition is characterized by its refined simplicity and elegant lines. The woman's dress, with its subtle patterns and flowing sleeves, and the delicate rendering of her features and hair, showcase Alexander's skill in capturing texture and form. The focus on the decorative qualities of the bowl and the overall harmonious arrangement of colors and shapes reflect Whistler's influence and the aesthetic concerns of the era. It is a quintessential example of Alexander's ability to create images of quiet beauty and refined sensibility.

Other Notable Portraits and Figurative Works

Beyond these specific masterpieces, Alexander produced numerous other significant portraits and figurative paintings. His portrait of Mrs. John White Alexander (Elizabeth Alexander) is a tender and insightful depiction of his wife. His portrait of the actress Maude Adams as Peter Pan captured the charm and whimsy of her famous role. Works like A Quiet Hour and Study in Black and Green further demonstrate his mastery of mood, color, and composition. Each of these paintings contributes to our understanding of Alexander as an artist deeply attuned to the nuances of human emotion and the aesthetic possibilities of paint.

Monumental Visions: Alexander's Murals

In addition to his easel paintings, John White Alexander made significant contributions to the art of mural painting, a field that experienced a renaissance in America during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, often referred to as the American Renaissance. Public buildings, libraries, and capitols were adorned with large-scale decorative schemes intended to edify and inspire the public.

The Library of Congress: A Crowning Achievement

Alexander's most extensive and celebrated mural project was for the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Commissioned in the 1890s for the Thomas Jefferson Building, his series of six large lunettes in the East Hall (then the Entrance Pavilion, North Hall, second floor) depicts "The Evolution of the Book." The panels trace the history of written communication from oral tradition and pictographs to the invention of printing. The subjects are:

1. The Cairn: Prehistoric man building a stone monument.

2. Oral Tradition: An Arab storyteller captivating an audience.

3. Egyptian Hieroglyphics: A scribe carving inscriptions.

4. Picture Writing: An American Indian painting on a deerskin.

5. The Manuscript Book: A medieval monk illuminating a manuscript.

6. The Printing Press: Gutenberg inspecting a proof sheet from his press.

These murals are characterized by their clear compositions, dignified figures, and harmonious color schemes, well-suited to the grand Beaux-Arts architecture of the building. Alexander's figures are idealized yet possess a sense of naturalism. He skillfully integrated them into the lunette shapes, creating balanced and visually engaging scenes. This project, alongside works by other artists like Edwin Howland Blashfield and Kenyon Cox in the same building, established Alexander as a leading muralist of his time.

Contributions to Other Public Spaces

Following the success of his Library of Congress murals, Alexander received other important mural commissions. He created a series of murals titled "The Apotheosis of Pittsburgh" (or "Pittsburgh, a City of Work") for the grand staircase of the Carnegie Institute (now the Carnegie Museum of Art) in his hometown of Pittsburgh. This ambitious project, completed between 1905 and 1908, depicted the city's industrial might through allegorical figures and scenes of labor. Unfortunately, some of these murals suffered from environmental damage over time.

He also designed murals for other public and private buildings, including the Pennsylvania State Capitol in Harrisburg and the New York Public Library. These large-scale works allowed Alexander to explore historical and allegorical themes on a grand scale, contributing to the civic and cultural landscape of America. His mural work demonstrated his versatility and his ability to adapt his style to the demands of monumental decoration, placing him in the company of other prominent American muralists like John La Farge and Elihu Vedder.

A Network of Artists: Contemporaries and Connections

John White Alexander was an active participant in the art worlds of both America and Europe, fostering relationships with a wide array of artists, writers, and cultural figures. These connections enriched his artistic development and helped to shape his career.

The American Scene: Sargent, Abbey, and Beyond

In America, Alexander was part of a generation of artists who sought to elevate the status of American art on the international stage. He was a contemporary of John Singer Sargent, whose dazzling brushwork and society portraits set a high bar. While Sargent's style was often more flamboyant, both artists shared an interest in elegant figuration and sophisticated compositions. Alexander also maintained a lifelong friendship with Edwin Austin Abbey, whom he had known since their early days at Harper's Weekly. Abbey, Sargent, Whistler, and Alexander were sometimes referred to as the "Four Great American Artists" of their time by contemporary critics, highlighting their international stature.

Alexander was also connected with other leading American artists, including William Merritt Chase, with whom he had studied in Munich, and Childe Hassam, a prominent American Impressionist. He was a respected member of various artistic organizations, including the National Academy of Design and the Society of American Artists. His interactions with these peers fostered a vibrant artistic dialogue and contributed to the growing sophistication of American art. He also collaborated with figures like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Beatty of the Carnegie Institute to promote American artists and organize exhibitions, helping to bring American art to a wider audience.

European Circles: From Rodin to Wilde

During his extended stays in Paris, Alexander moved in prominent artistic and literary circles. He was acquainted with the sculptor Auguste Rodin, whose powerful and expressive works were revolutionizing sculpture. He also knew writers such as Henry James and Oscar Wilde, figures who, like Alexander, navigated the cultural currents between Europe and America. His friendship with Octave Mirbeau, an influential French art critic and novelist, further connected him to the Parisian avant-garde.

These European connections exposed Alexander to a wide range of artistic ideas and movements, from the lingering influence of academicism to the innovations of Symbolism and Art Nouveau. His ability to absorb these influences while maintaining his own artistic identity was a hallmark of his career. His international network also facilitated the exhibition and reception of his work abroad, contributing to his widespread acclaim.

Champion of the Arts: Public Service and Advocacy

John White Alexander's commitment to the arts extended beyond his own creative endeavors. He dedicated considerable time and energy to arts administration and advocacy, playing an important role in shaping American cultural institutions.

He was actively involved with the National Academy of Design in New York, one of the country's oldest and most prestigious art organizations. He was elected an Associate Member in 1901 and a full Academician in 1902. From 1909 to 1915, he served as President of the National Academy of Design. During his tenure, he worked to modernize the institution, promote American artists, and enhance the quality of its exhibitions and educational programs. He was known for his diplomatic skills and his ability to unite diverse factions within the art community.

Alexander was also a trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and was involved with other cultural organizations, such as the MacDowell Club, which supported artists in various disciplines. He was a strong advocate for art education and believed in the importance of public access to art. He provided art instruction in New York public schools and was a generous mentor to younger artists, offering encouragement and support. His efforts helped to foster a more vibrant and supportive environment for the arts in America. In recognition of his artistic achievements and his contributions to Franco-American cultural relations, he was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor by the French government in 1901.

Personal Life and Enduring Challenges

While John White Alexander achieved considerable professional success, his life was not without personal challenges. He suffered from chronic health problems throughout much of his career. Sources indicate he dealt with long-term illness and experienced occasional epileptic seizures. These health issues sometimes impacted his ability to work and forced him to pace himself. For instance, in 1908, his declining health meant he had to rely on previously exhibited works for annual shows.

Despite these physical ailments, Alexander maintained a productive career and a public persona of grace and professionalism. His marriage to Elizabeth Alexander in 1887 was a source of stability and support. Elizabeth, often known as "Bessie," was a cultivated woman from a prominent New York family. Her social connections undoubtedly benefited Alexander's career, particularly in securing portrait commissions. They had one son, James Waddell Alexander II (1888–1971), who, despite his father's artistic inclinations, pursued a distinguished career in mathematics, becoming a renowned topologist at Princeton University.

The Alexanders divided their time between New York and Europe, particularly Paris, for many years. They also had a summer home in Onteora Park in the Catskill Mountains, an exclusive arts colony frequented by writers, artists, and intellectuals. This provided a retreat from the demands of city life and a stimulating environment for creative work.

Later Years and Lasting Legacy

John White Alexander continued to paint and remain active in the art world until his death. He was working on murals for the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh in his final years, a project that remained unfinished at the time of his passing. He died in New York City on May 31, 1915, at the age of 58, following a period of declining health. His death was widely mourned in both American and European art circles.

In the decades immediately following his death, Alexander's reputation, like that of many artists of his generation who worked in a more traditional or Symbolist vein, experienced a period of relative neglect as Modernist movements like Cubism and abstraction came to dominate the art world. However, a renewed appreciation for Gilded Age art and the diverse currents of turn-of-the-century painting has led to a reassessment of his work.

Today, John White Alexander is recognized for his distinctive contribution to American art. His paintings are prized for their elegance, technical skill, and evocative power. His portraits capture the likeness and character of his sitters, while his subject pictures and murals explore universal themes of beauty, emotion, and human history. His works are held in major museum collections across the United States, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

His archives, including correspondence, sketchbooks, and photographs, are preserved at the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, providing valuable insights into his life, work, and the artistic milieu in which he operated. These records document his extensive network of contacts and his significant role in the cultural life of his time.

John White Alexander in Art History: An Enduring Influence

John White Alexander occupies an important place in American art history as a bridge figure. He successfully synthesized various late 19th-century artistic trends – the tonalism of Whistler, the decorative linearity of Art Nouveau, the evocative mood of Symbolism, and the lingering elegance of academic portraiture – into a style that was both personal and reflective of its era. He was a key figure in the "American Renaissance," a period when American artists sought to create a national art that could stand alongside European achievements.

His depictions of women, in particular, have become iconic images of the Gilded Age, embodying its ideals of refinement, grace, and introspection. While not an avant-garde radical, Alexander was an innovator in his own right, particularly in his use of materials and his emphasis on design and decorative harmony. His murals contributed to the tradition of public art in America, bringing art to a wider audience and enriching civic spaces.

As an influential arts administrator and educator, he helped to shape the institutions that supported American art and artists. His presidency of the National Academy of Design and his support for younger artists demonstrated his commitment to fostering a vibrant artistic culture. John White Alexander's legacy endures through his beautiful and evocative paintings, which continue to captivate viewers with their timeless elegance and subtle emotional depth, securing his position as one of the most accomplished American painters of his generation.