The Victorian era in Great Britain was a period of immense artistic production, diversity, and burgeoning public interest in art. While grand historical narratives, evocative landscapes, and insightful portraits often captured the limelight, the quieter genre of still life also flourished, finding favour with a growing middle-class clientele. Among the many talented artists dedicated to this genre was Thomas Worsey (1829-1875), a painter celebrated for his exquisitely detailed and richly coloured depictions of fruit, flowers, and bird's nests. His work, though perhaps not as widely known today as some of his bombastic contemporaries, represents a significant strand in the rich tapestry of 19th-century British art.

This exploration will delve into the life and art of Thomas Worsey, the painter, placing him within the artistic currents of his time. We will also take a moment to clarify some common confusions that arise due to individuals with similar names from different historical periods, ensuring our focus remains firmly on the 19th-century artist whose canvases brought the beauty of nature's bounty into Victorian homes.

Clarifying Identities: The Worsey and Wolsey Names

Before proceeding to the life and work of Thomas Worsey, the Victorian painter, it is crucial to address a point of potential confusion arising from the provided information. The art historical record features several prominent figures whose names bear similarity, leading to occasional misattributions.

The initial information provided for this article appeared to conflate Thomas Worsey (1829-1875) with Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (c. 1473–1530). Cardinal Wolsey was a powerful English statesman and a cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church during the reign of King Henry VIII. He was a significant patron of architecture, most famously commissioning parts of Hampton Court Palace. His life, political career, and dramatic fall from grace are well-documented historical events of the Tudor period, entirely separate from the 19th-century painter.

Furthermore, references to a "Surveyor General" appointed in 1760, working with architects like Robert Adam and William Chambers, point to a different individual altogether, likely Thomas Worsley (1710-1778) of Hovingham Hall, who indeed held that post and was an accomplished amateur architect and connoisseur. This 18th-century figure is distinct from both Cardinal Wolsey and the Victorian painter Thomas Worsey. The description of an "amateur architect" for Thomas Worsey (1829-1875) in the initial prompt seems to be a misattribution or a lesser-known facet not typically associated with his primary career as a painter.

Finally, the mention of Charles Annesley Voysey (1857-1941) also refers to a different, albeit highly influential, figure. C.A. Voysey was a prominent English architect and designer associated with the Arts and Crafts movement, known for his distinctive domestic architecture and designs for furniture, wallpaper, and textiles.

With these distinctions clarified, this article will now focus solely on Thomas Worsey (1829-1875), the artist renowned for his still-life paintings.

The Life and Career of Thomas Worsey, the Painter

Thomas Worsey was born in the town of Birmingham, England, in 1829. Birmingham, during this period, was a rapidly industrializing city, a hub of manufacturing and innovation. It also possessed a burgeoning artistic community. While detailed specifics of Worsey's early life and formal artistic training are not extensively documented, it is evident from the quality and technical proficiency of his work that he received a solid grounding in the academic principles of drawing and painting.

Many aspiring artists of his time would have sought instruction at local art schools or academies, or perhaps apprenticed with established painters. The Birmingham School of Art (founded in 1843 as the Birmingham Government School of Design) would have been a potential institution for artists in the region. Regardless of his specific path, Worsey developed a remarkable skill for detailed observation and meticulous rendering, qualities that would become hallmarks of his artistic output.

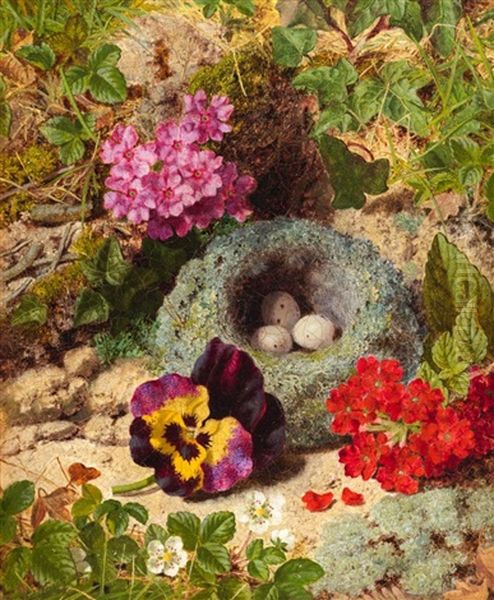

Worsey's career unfolded primarily during the mid-Victorian period, an era characterized by a strong public appetite for art that was both aesthetically pleasing and demonstrative of technical skill. He specialized in still life, a genre that, while sometimes considered lower in the academic hierarchy than history painting or portraiture, enjoyed considerable popularity. His chosen subjects were typically arrangements of fruit and flowers, often complemented by bird's nests, mossy banks, or delicate insects. These compositions were celebrated for their vibrant colours, intricate detail, and convincing illusionism.

Artistic Style and Subject Matter

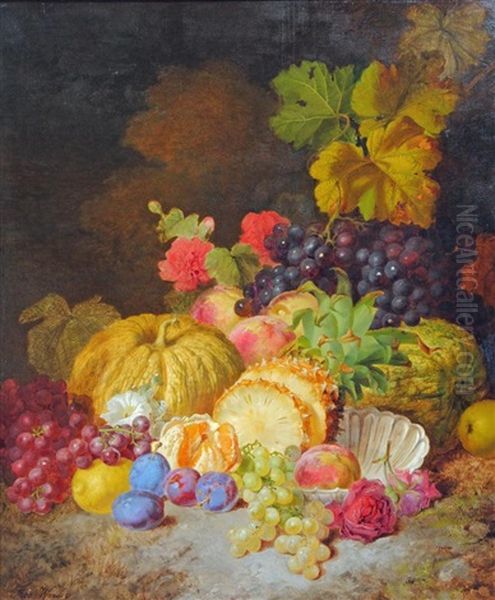

Thomas Worsey's artistic style is firmly rooted in the tradition of detailed realism that was highly valued in much of Victorian art. He worked predominantly in oils, a medium that allowed for rich colour saturation and the subtle blending required to achieve lifelike textures. His paintings are characterized by a high degree of finish, with brushstrokes often carefully smoothed to create an almost photographic clarity.

His depictions of fruit – grapes, peaches, plums, strawberries – are particularly noteworthy. Each piece of fruit is rendered with individual attention, capturing the bloom on a grape, the fuzz on a peach, or the glistening surface of a dewdrop. Worsey paid close attention to the play of light and shadow, using it to model forms and create a sense of three-dimensionality. The textures are palpable: the velvety skin of a peach, the crispness of an apple, the delicate translucency of a currant.

Flowers were another favourite subject. He painted roses, primroses, fuchsias, and other garden and wild varieties with botanical accuracy, yet his arrangements often possessed a natural, unforced quality. Unlike the more formal and sometimes rigid floral compositions of earlier periods, Worsey's flowers often appear as if freshly gathered and casually arranged, sometimes spilling from a basket or nestled on a mossy bank. This approach aligned with the Victorian appreciation for nature, even in its cultivated forms.

The inclusion of bird's nests, complete with delicately speckled eggs, added a touch of poignant naturalism to his works. These elements, often rendered with painstaking care, evoked the intricacies of the natural world and perhaps resonated with the Victorian interest in natural history and ornithology, an interest also seen in the works of artists like William Henry Hunt, who was renowned for his bird's nest subjects.

Worsey's compositions were typically well-balanced, often employing a pyramidal or clustered arrangement of objects. Backgrounds were generally dark and unobtrusive, serving to throw the brightly lit subjects into sharp relief, a technique reminiscent of some Dutch Golden Age still-life painters like Jan Davidsz. de Heem or Willem Kalf, whose influence can be felt in the broader Victorian still-life tradition.

Representative Works and Exhibitions

Thomas Worsey was a prolific artist, and his works were regularly exhibited at prestigious venues, which was crucial for an artist's reputation and commercial success in the 19th century. He exhibited extensively at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, a key institution for any ambitious British painter. His presence there, from 1857 to 1874, indicates a consistent level of quality and acceptance by the art establishment.

He also showed his paintings at the British Institution and the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA) on Suffolk Street, among other galleries. Titles of his exhibited works often directly reflected their subject matter, such as "Still Life: Fruit," "Flowers and Fruit," "A Bird's Nest and Primroses," or "Grapes, Peaches, and Plums." While specific named masterpieces are not always singled out in the same way as for, say, a history painter, the collective body of his exhibited work solidified his reputation.

One can imagine a typical Worsey canvas: a tabletop or mossy bank laden with a profusion of ripe fruit. Sunlight catches the translucent skin of green and purple grapes, a downy peach nestles beside a gleaming apple, and perhaps a few strawberries add a splash of vibrant red. Nearby, a meticulously painted bird's nest might hold a clutch of pale blue eggs, a ladybug or butterfly alighting on a leaf. The overall effect would be one of abundance, natural beauty, and extraordinary technical skill. These works appealed to the Victorian desire for verisimilitude and the appreciation of nature's bounty, making them desirable additions to domestic interiors.

The Context of Victorian Still-Life Painting

To fully appreciate Thomas Worsey's contribution, it is essential to understand the context of still-life painting in Victorian England. The genre had a long and distinguished history, tracing its roots back to the lavish works of 17th-century Dutch and Flemish masters. Artists like Jan van Huysum and Rachel Ruysch set a high bar for floral and fruit painting, and their influence resonated through subsequent centuries.

In Victorian Britain, still life found a receptive audience. The burgeoning middle class, enriched by industrial and commercial expansion, sought art to adorn their homes. Still-life paintings, with their often accessible subject matter and decorative qualities, were highly suitable. They could be appreciated for their beauty, the skill of their execution, and sometimes for their symbolic content, although overt moralizing symbolism was less prevalent in Worsey's work than in some earlier still lifes.

Several other artists excelled in still life during this period. George Lance (1802-1864) was a prominent predecessor and contemporary known for his opulent fruit pieces. William Henry Hunt (1790-1864), often associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood through his champion John Ruskin, was celebrated for his incredibly detailed watercolours of fruit, flowers, and particularly bird's nests. His meticulous technique, often involving stippling, set a standard for precision.

Female artists also made significant contributions to the still-life genre. The Mutrie sisters, Martha Darley Mutrie (1824-1885) and Annie Feray Mutrie (1826-1893), were highly regarded for their flower paintings, as was Helen Cordelia Angell (née Coleman) (1847-1884), who was particularly known for her vibrant watercolours of flowers and dead birds. These artists, like Worsey, catered to a market that valued detailed naturalism and pleasing compositions.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in 1848 by artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt, also had an indirect influence on the broader Victorian art scene through their emphasis on truth to nature and meticulous detail. While Worsey was not a Pre-Raphaelite, the movement's insistence on close observation of the natural world resonated with the detailed approach seen in many still-life paintings of the era. Millais's early works, such as "Ophelia," with its incredibly detailed rendering of riverside flora, showcase this Pre-Raphaelite commitment to botanical accuracy.

Other prominent Victorian painters working in different genres also shaped the artistic landscape. Figure painters like William Powell Frith captured bustling scenes of modern life, while Sir Edwin Landseer was renowned for his animal paintings. Landscape artists continued the traditions of J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, with figures like Myles Birket Foster producing charming rural scenes. The Royal Academy was dominated by figures like Frederic Leighton and Sir Edward Poynter, who championed classical and historical subjects. Worsey's career unfolded amidst this diverse and dynamic art world.

Worsey's Place and Legacy

Thomas Worsey operated within a well-established and popular genre. His strength lay not necessarily in radical innovation but in the consistent excellence and refinement of his technique. He was a master of his craft, capable of producing works that delighted the eye with their verisimilitude and rich, harmonious colours. His paintings offered an escape into a world of natural beauty, a welcome contrast to the often-grimy realities of industrial Britain.

His works were collected by private individuals and likely found their way into many Victorian homes. Today, his paintings appear in art auctions and are held in various public and private collections. While he may not have achieved the overarching fame of some of his contemporaries who tackled grander themes or pioneered new artistic movements, Thomas Worsey holds a secure place as a highly skilled and respected practitioner of still-life painting in the Victorian era.

His dedication to capturing the minute details of nature, the lusciousness of fruit, and the delicate beauty of flowers, connects him to a long tradition of artists who found profound inspiration in the seemingly simple objects of the everyday world. He contributed to a visual culture that valued craftsmanship, realism, and the appreciation of nature's artistry. Artists like George Clare (c.1835-1900) and Oliver Clare (1853-1927), who painted in a similar detailed style, particularly fruit and flower subjects often on mossy banks, can be seen as continuing in a similar vein, demonstrating the enduring appeal of this type of still life.

The broader artistic environment of Worsey's time also included influential critics like John Ruskin, whose writings championed artists who adhered to "truth to nature," a principle that Worsey's work certainly embodied. While Ruskin's primary focus was often on landscape and the Pre-Raphaelites, his emphasis on detailed observation had a wide-ranging impact on Victorian aesthetic sensibilities.

Conclusion: The Enduring Appeal of Worsey's Art

Thomas Worsey (1829-1875) was a quintessential Victorian still-life painter. His career, though relatively short, was marked by a consistent output of high-quality works that found favour with the exhibition-going public and private collectors. He excelled in rendering the textures, colours, and forms of fruit, flowers, and bird's nests with a meticulous attention to detail that was characteristic of the era's taste.

While the grand narratives of history painting or the revolutionary zeal of avant-garde movements might often dominate art historical discourse, the quieter, more intimate genre of still life, as practiced by artists like Worsey, played an essential role in the artistic life of the 19th century. His paintings brought beauty, craftsmanship, and a deep appreciation for the natural world into the homes of his patrons.

In distinguishing him from other historical figures with similar names, such as Cardinal Thomas Wolsey or the 18th-century Surveyor General Thomas Worsley, we can better appreciate the specific contributions of Thomas Worsey, the painter. His legacy is that of a dedicated and highly skilled artist who mastered his chosen genre, leaving behind a body of work that continues to delight viewers with its precision, vibrancy, and celebration of nature's intricate beauty. His art serves as a testament to the enduring appeal of still life and the rich artistic fabric of the Victorian age, an age that also saw the talents of painters ranging from the academic classicism of Lawrence Alma-Tadema to the social realism of Luke Fildes, and the aestheticism of James McNeill Whistler. Thomas Worsey, in his own focused way, contributed significantly to this diverse artistic output.