Vasili Andreevich Tropinin stands as a remarkable figure in the annals of Russian art, a testament to innate talent triumphing over the profound adversity of serfdom. His life story is as compelling as his artistic output, offering a unique lens through which to view early 19th-century Russian society and its burgeoning national artistic identity. Known primarily for his intimate and realistic portraits, Tropinin captured the spirit of his age, particularly the burgeoning Moscow middle class, with a warmth and directness that set him apart from many of his contemporaries.

Early Life and the Bonds of Serfdom

Vasili Andreevich Tropinin was born in March 1776 (or possibly 1780, sources vary slightly) in the village of Karpovo, Novgorod Governorate, into the status of a serf. His father, Andrei Ivanovich, was a serf belonging to Count Anton Sergeevich Minikh. Shortly after Vasili's birth, as part of a dowry, he and his family were transferred to Count Irakly Ivanovich Morkov (also spelled Markov). This change in ownership would profoundly shape the young artist's life, as Count Morkov recognized Tropinin's burgeoning artistic talent but also subjected him to the whims and duties expected of a serf.

The institution of serfdom in Russia was a deeply entrenched system of feudal dependency, where peasants were bound to the land and to their noble landowners. They could be bought, sold, or inherited, and their lives were largely dictated by their masters. For an individual with artistic aspirations, this status presented almost insurmountable obstacles. Access to formal education, materials, and, most importantly, freedom to pursue one's craft, were privileges largely denied to serfs.

Despite these constraints, Tropinin's artistic inclinations were evident from a young age. Count Morkov, noticing his talent, initially allowed him to receive some rudimentary training. This was not an act of pure altruism; talented serfs could enhance a nobleman's estate and prestige. However, Morkov's support was inconsistent and often secondary to Tropinin's other duties.

Initial Artistic Training and Interrupted Studies

Around 1798, Count Morkov decided to send the young Tropinin to Saint Petersburg to train as a confectioner. This seemingly unrelated apprenticeship was a common path for serfs intended for household service. However, while in the capital, Tropinin's artistic passion persisted. He managed to secretly attend drawing classes, and eventually, Morkov was persuaded, possibly by his cousin Alexei Ivanovich Morkov, to allow Tropinin to study at the Imperial Academy of Arts as an external student (auditor).

At the Academy, Tropinin studied under the esteemed portraitist Stepan Semyonovich Shchukin, a prominent figure in Russian Neoclassicism. Shchukin's influence was significant, providing Tropinin with a solid foundation in academic drawing and painting techniques. During this period, Tropinin showed considerable promise, even exhibiting a work, "Boy Grieving for a Dead Bird" (1804), which was noted by Empress Maria Feodorovna herself. This early recognition hinted at a bright future.

However, Tropinin's formal artistic education was abruptly cut short. In 1804, Count Morkov, perhaps fearing the loss of a valuable asset or simply needing his services, recalled Tropinin from Saint Petersburg. This decision forced Tropinin to abandon his studies at a crucial stage in his development, a bitter blow for the aspiring artist.

The Ukrainian Period: Art Amidst Servitude

Upon his recall, Tropinin was sent to Count Morkov's newly acquired estate in Kukavka, Podolia (now in Ukraine). Here, his life took a different turn. He was tasked with a variety of roles, including that of a lackey, a pastry chef, and even an estate manager. Simultaneously, Morkov utilized Tropinin's artistic skills for personal projects, commissioning him to copy works by Western European masters and to paint portraits of the Morkov family. He was also tasked with decorating the local church in Kukavka, a project that allowed him some creative freedom.

This period in Ukraine, lasting nearly two decades, was formative for Tropinin. While deprived of the sophisticated artistic environment of Saint Petersburg, he was immersed in the local culture and the lives of ordinary Ukrainian peasants. This experience deeply influenced his artistic vision, fostering an appreciation for genre scenes and the unadorned beauty of everyday life. Works from this period, such as "The Spinner" and portraits of local people, reflect a growing interest in capturing individual character and a sense of quiet dignity.

During his time in Kukavka, Tropinin married Anna Ivanovna Katina, also a serf. They had a son, Arseny, who would later become an artist himself, often assisting his father. The responsibilities of family life, coupled with his duties to Count Morkov, made the dream of artistic freedom seem even more distant.

The Long-Awaited Freedom and Rise to Prominence in Moscow

The desire for freedom was a constant undercurrent in Tropinin's life. Despite his talent and the relative comfort he might have enjoyed compared to field serfs, the stigma and limitations of his status were undeniable. Finally, in 1823, at the age of 47, Vasili Tropinin was granted his freedom by Count Morkov. The reasons for this belated manumission are not entirely clear; it may have been due to persistent petitions, the changing social climate, or perhaps Morkov's eventual recognition of the injustice of keeping such a talent in bondage. However, his wife and son remained serfs for several more years, a source of continued anxiety for the artist.

Upon gaining his freedom, Tropinin moved to Moscow. This city, with its distinct cultural identity, less formal than Saint Petersburg, proved to be a welcoming environment for his art. In 1823, he presented his paintings "The Lacemaker," "The Beggar," and "Portrait of the Engraver E.O. Skotnikov" to the Imperial Academy of Arts. On the strength of these works, particularly "The Lacemaker," he was awarded the title of "appointed academician." A year later, in 1824, for his "Portrait of K.A. Leberecht," he was made a full Academician.

Moscow became Tropinin's artistic home. He quickly established himself as a leading portraitist, sought after by the city's nobility, merchants, intellectuals, and fellow artists. His studio became a popular gathering place, and he was known for his amiable personality and his ability to put his sitters at ease, resulting in portraits that were both lifelike and psychologically insightful.

Artistic Style: Intimacy, Realism, and the "Moscow School"

Tropinin's artistic style is characterized by its intimate realism, warmth, and a focus on the individual character of his sitters. He moved away from the idealized, often grandiose, portraiture favored by some of his academic contemporaries, opting instead for a more direct and unpretentious approach. This resonated particularly well with the Moscow clientele, who appreciated the sincerity and lack of affectation in his work.

His portraits often feature simple compositions, with the sitter depicted in a relaxed, natural pose, frequently engaged in a characteristic activity or surrounded by objects that speak to their profession or personality. He had a keen eye for detail, rendering textures and fabrics with skill, but these details never overshadowed the human element. His use of light was often soft and diffused, contributing to the gentle and approachable atmosphere of his paintings.

Tropinin is often considered a key figure in the "Moscow School" of painting, which contrasted with the more formal and Western-oriented "Saint Petersburg School." The Moscow artists tended to favor more intimate genres, a closer connection to Russian national life, and a less rigidly academic style. Tropinin's work epitomized these qualities. He painted not only the aristocracy but also ordinary people, infusing his depictions of peasants, craftsmen, and domestic servants with a sense of dignity and humanity.

Key Masterpieces: Capturing the Essence of an Era

Several of Tropinin's works have become iconic representations of Russian art in the first half of the 19th century.

"The Lacemaker" (1823): Perhaps his most famous painting, "The Lacemaker" is a quintessential example of Tropinin's charm and skill. It depicts a young woman, her head slightly bowed, engrossed in the delicate task of lacemaking. The painting is celebrated for its tender portrayal of youthful diligence, the subtle play of light on her face and hands, and the meticulous rendering of the lace and bobbins. It captures a quiet moment of everyday life with grace and sensitivity, elevating a simple genre scene to a work of high art. This piece was instrumental in securing his title of "appointed academician."

"Portrait of Alexander Pushkin" (1827): Tropinin painted several portraits of Russia's greatest poet, Alexander Pushkin. The most famous of these shows Pushkin in a relaxed, informal pose, wearing a dressing gown. Tropinin captures the poet's intelligent gaze and restless energy, offering a more personal and approachable image than some of the more formal depictions by other artists like Orest Kiprensky. This portrait became one of the most recognizable images of Pushkin.

"Portrait of Arseny Tropinin, the Artist's Son" (c. 1818): This tender portrait of his young son, likely painted while still in Kukavka, showcases Tropinin's ability to capture the innocence and vulnerability of childhood. The boy looks directly at the viewer with a serious yet gentle expression. It is a deeply personal work, reflecting the artist's paternal affection.

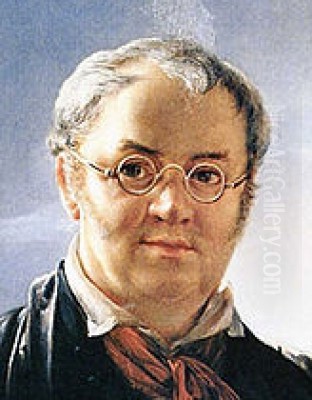

"Self-Portrait with Brushes and Palette against a Window with a View of the Kremlin" (1846): In this late self-portrait, Tropinin presents himself as a confident and established artist. He stands before a window offering a view of the Moscow Kremlin, symbolizing his deep connection to the city that embraced him. The work conveys a sense of quiet pride and accomplishment.

"The Gold-Embroideress" (1826): Similar in spirit to "The Lacemaker," this painting depicts a young woman meticulously working on gold embroidery. Tropinin again demonstrates his skill in capturing the focused concentration of his subject and the intricate details of her craft. The warmth of the colors and the gentle expression of the embroideress create an image of serene industry.

Other notable works include numerous portraits of Moscow's elite and common folk, such as "Portrait of P.A. Bulakhov" (1823), "The Guitar Player" (1820s-1830s), and "Man with a Book (Portrait of N.M. Karamzin)" (1818), showcasing his consistent ability to reveal the inner life of his subjects.

Tropinin and His Contemporaries: A Network of Russian Artists

Vasili Tropinin's career unfolded during a vibrant period in Russian art, and he interacted with, and was compared to, several key figures.

His primary teacher, Stepan Shchukin (1754–1828), was a respected academician whose neoclassical style provided Tropinin with a strong technical grounding. However, Tropinin's mature style diverged significantly from Shchukin's more formal approach.

A prominent contemporary and, in some ways, a rival in the field of portraiture was Orest Kiprensky (1782–1836). Kiprensky, often associated with Romanticism, produced powerful and psychologically intense portraits, such as his famous depiction of Alexander Pushkin. While both artists painted Pushkin, their interpretations differed: Kiprensky's was more heroic and Byronic, while Tropinin's was more intimate and informal. Their styles represented two distinct currents in Russian portraiture of the era.

Karl Bryullov (1799–1852) was another towering figure, known for his monumental historical paintings like "The Last Day of Pompeii," but also a gifted portraitist. Bryullov's work was often more dramatic and theatrical than Tropinin's, reflecting a different artistic temperament and ambition. While Bryullov achieved international fame, Tropinin remained deeply rooted in the Moscow art scene.

Alexey Venetsianov (1780–1847) shared Tropinin's interest in depicting ordinary Russian life and peasants. Venetsianov, however, often idealized his peasant subjects, imbuing them with a poetic grace, and he established his own school of art focused on genre painting. Tropinin's genre scenes and portraits of commoners tended to be more direct and less overtly sentimentalized, though equally empathetic.

Later artists like Pavel Fedotov (1815–1852), considered a forerunner of Critical Realism in Russia, built upon the foundations laid by artists like Tropinin and Venetsianov in terms of depicting everyday life, though Fedotov's work carried a stronger satirical and social-critical edge.

Other important artists of the period whose careers overlapped or intersected with Tropinin's include:

Vladimir Borovikovsky (1757–1825): A leading portraitist of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, known for his sentimental and elegant style. Tropinin's work can be seen as a shift towards greater realism from Borovikovsky's era.

Dmitry Levitzky (1735–1822): Another giant of 18th-century Russian portraiture, whose sophisticated and characterful portraits set a high standard for subsequent generations.

Sylvester Shchedrin (1791–1830): A renowned landscape painter, representing another facet of the flourishing Russian art scene.

Alexander Varnek (1782–1843): A contemporary portraitist and genre painter, also an academician, whose career paralleled Tropinin's in some respects.

Fyodor Rokotov (1735–1808): An earlier master of the intimate portrait, whose subtle psychological insights prefigured some of Tropinin's own achievements.

Ivan Argunov (1729-1802): One of the founders of the Russian school of portrait painting, himself a serf artist who gained renown, providing an earlier, though less common, precedent for artists like Tropinin.

Tropinin's interactions with these artists, whether as a student, a colleague, or a friendly competitor, enriched the artistic landscape of Russia. He was particularly respected in Moscow, where his studio was a hub for artists and intellectuals.

Anecdotes and Character: The Man Behind the Brush

Several anecdotes illuminate Tropinin's character and the circumstances of his life. The very fact of his long servitude and late freedom is the most significant "story" of his life, highlighting his perseverance. Contemporaries described him as modest, kind-hearted, and hardworking.

One story tells of his diligence even while serving as a confectioner for Count Morkov. He would reportedly use any spare moment and material, even dough, to practice sculpting and drawing, a testament to his unwavering artistic drive.

His popularity in Moscow was immense. It was said that "all of Moscow" wanted a portrait by Tropinin. He was not just an artist but a beloved city figure. His ability to connect with his sitters on a personal level was key to his success. He didn't just paint their likeness; he seemed to capture their soul.

The delay in freeing his wife and son after his own manumission was a source of great distress for Tropinin. He worked tirelessly, saving money and petitioning for their freedom, which was eventually granted in 1828. This personal struggle underscores the human cost of the serf system, even for those who achieved a measure of success.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Vasili Andreevich Tropinin passed away in Moscow on May 3 (15), 1857, and was buried at the Vagankovo Cemetery. He left behind a rich artistic legacy, comprising over 3,000 works, primarily portraits. His influence on Russian art was profound and lasting.

Tropinin played a crucial role in the development of a distinctly Russian school of portraiture, one that valued intimacy, psychological depth, and a realistic depiction of individuals from various walks of life. He democratized the portrait, moving it away from solely representing aristocratic grandeur to embracing the character of the broader populace.

His work provided a bridge between the more formal traditions of the 18th century and the burgeoning realism of the mid-19th century. Artists of the later Peredvizhniki (Wanderers) movement, who championed realism and social commentary, owed a debt to pioneers like Tropinin who had already begun to turn their gaze towards the authentic representation of Russian people and their lives.

The Tropinin Museum in Moscow, established in 1969, stands as a dedicated repository of his works and those of his Moscow contemporaries, ensuring that his contributions to Russian art are preserved and celebrated. His paintings continue to be admired for their technical skill, their warmth, and their insightful portrayal of a bygone era.

Conclusion: A Triumph of Spirit and Art

Vasili Andreevich Tropinin's journey from the constraints of serfdom to the heights of artistic acclaim is a powerful narrative of resilience and talent. His art, characterized by its warmth, sincerity, and profound humanism, offers an invaluable window into 19th-century Russian society. He not only captured the likenesses of his contemporaries but also their spirit, creating a gallery of characters that feel alive and relatable even today. His legacy is not just in the beautiful canvases he left behind, but in the enduring message that art can flourish even in the most challenging circumstances, and that the truthful depiction of humanity holds timeless appeal. Tropinin remains a beloved figure in Russian art history, a master of the intimate portrait, and an inspiration.