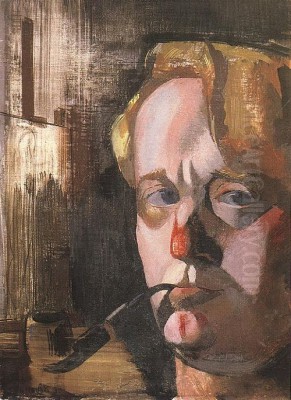

Vilmos Aba-Novák stands as a towering figure in twentieth-century Hungarian art. Born in Budapest on March 15, 1894, and passing away prematurely on September 29, 1941, his relatively short life coincided with a period of immense artistic ferment and national transformation in Hungary and across Europe. Aba-Novák navigated these turbulent times, forging a unique artistic identity that blended native traditions with international modernist currents. He became renowned not only for his vibrant easel paintings but also, and perhaps most significantly, for his powerful, large-scale murals, establishing himself as a master of monumental art with a distinctive voice. His work resonates with energy, bold color, and a deep connection to Hungarian life and history.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Aba-Novák's journey into art began in his native Budapest. He pursued formal training at the city's prestigious Academy of Fine Arts, immersing himself in the academic traditions that still held sway at the beginning of the 20th century. His education, however, was interrupted by the cataclysm of World War I. Like many young men of his generation, he served in the Austro-Hungarian army, an experience that undoubtedly left its mark on his worldview, though its direct reflection in his later art is often more symbolic than literal.

Following the war, Aba-Novák returned to his artistic studies. This period saw him absorbing various influences. He studied under figures like Viktor Olgyay at the Munkácsy Realist School, grounding him in certain traditions of Hungarian painting. Sources also suggest connections or shared learning environments with established or contemporary Hungarian artists such as the influential landscape painter László Mednyánszky and János Thorma, a key figure associated with the Nagybánya artists' colony. These early interactions exposed him to different facets of Hungarian art, from plein-air naturalism to more Symbolist tendencies.

The artistic environment of post-war Hungary was dynamic. Artists were grappling with national identity, the trauma of war, and the influx of modernist ideas from Paris, Vienna, and Berlin. Aba-Novák spent time working in artists' colonies, notably Szolnok on the Great Hungarian Plain and potentially Baia Mare (Nagybánya) in Transylvania (now Romania). These colonies were vital centers for artistic exchange and the development of distinctly Hungarian approaches to modern painting, often focusing on rural life and landscapes. It was within this milieu that Aba-Novák began to synthesize his training and experiences, searching for his own artistic path.

Forging a Unique Style: Synthesis and Dynamism

A pivotal moment in Aba-Novák's development occurred during the mid-1920s. Like many ambitious artists of his time, he was drawn to Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world. His time there, particularly around 1925, proved highly influential. He encountered firsthand the latest currents of French art, including the lingering impact of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, as well as newer movements. This exposure seems to have catalyzed a shift in his work towards brighter palettes and more dynamic compositions.

Returning to Hungary, Aba-Novák began to forge a highly personal style. He masterfully blended the international influences he had absorbed with elements deeply rooted in Hungarian culture. His work from this period often exhibits characteristics associated with Expressionism – a focus on subjective experience, emotional intensity, and often bold, non-naturalistic use of color. However, he tempered this with a strong decorative sense, possibly influenced by Hungarian folk art traditions and the burgeoning Art Deco movement.

A key aspect of his style was its sheer energy. His canvases depicting bustling village markets, chaotic circuses, or lively folk festivals pulse with movement. He achieved this through vigorous brushwork, often employing what some sources describe as a "dissolving boundaries" technique. This involved using dynamic lines and somewhat blurred edges between forms, avoiding static outlines and allowing figures and background elements to merge in a vibrant tapestry of color and motion. This technique imbued his scenes with a sense of immediacy and vitality.

His subject matter frequently centered on Hungarian peasant life, but not in a purely ethnographic or romanticized way. He captured the raw energy, the spectacle, and sometimes the underlying tensions of these scenes. Works like Circus (c. 1926) and Village Market (c. 1935) exemplify this approach. They are characterized by their crowded compositions, expressive figures, and a palette that, while bright and often joyous, could also incorporate dramatic contrasts, creating a dreamlike or heightened reality. He was also drawn to depicting dramatic events, such as the devastating Flood on the Tisza River (1931), showcasing his ability to handle large-scale, narrative compositions even on canvas.

The Influence of Italy: Novecento and Monumentality

Another significant influence, particularly evident in his later work and especially his murals, was Italian art. Aba-Novák spent time in Rome on a scholarship between 1928 and 1930. This period exposed him to both the grandeur of historical Italian frescoes and the contemporary Italian art movement known as the Novecento Italiano. The Novecento artists, reacting against the pre-war avant-garde, sought a "return to order," drawing inspiration from classical and Renaissance traditions while retaining a modern sensibility. Figures like Mario Sironi and Achille Funi were creating monumental public works that emphasized clarity, solid forms, and often national themes.

This Italian experience resonated deeply with Aba-Novák and significantly shaped his approach to large-scale public art. He began to receive major commissions for murals, a field in which he would achieve lasting fame. His technique adapted, incorporating principles suited to monumental decoration. While retaining his characteristic energy, his mural style often featured clearer compositions, more defined figures, and a narrative focus, aligning with the Novecento emphasis on order and communicability within a modern framework. He became a master of fresco and secco techniques, adapting them to his expressive needs.

The Monumental Vision: Murals and Public Art

Aba-Novák's legacy is inextricably linked to his monumental mural projects, which represent some of the most significant public art commissions in interwar Hungary. These works allowed him to explore historical, religious, and national themes on an ambitious scale, engaging a wider public beyond the gallery setting.

One of his most celebrated achievements is the series of frescoes for the Roman Catholic Church in Jászszentandrás, completed around 1937. These works depict religious scenes with his characteristic dynamism and vibrant color, translating biblical narratives into his unique visual language. They demonstrate his ability to integrate his art seamlessly within an architectural space while conveying profound spiritual and human themes.

Perhaps his most famous mural project is the decoration of the Hősök Kapuja (Heroes' Gate) in Szeged, also completed in 1937. This monumental archway was built to commemorate the soldiers from Szeged who died in World War I. Aba-Novák covered vast surfaces of the gate's interior vault and walls with frescoes. The scale is immense, reportedly making it one of the largest outdoor (or semi-outdoor, being under the arch) mural ensembles in Europe at the time. The frescoes depict scenes related to Hungarian history, civic life, and allegories connected to the sacrifices of war, rendered with dramatic intensity and a powerful narrative drive.

Another significant commission was the mural cycle for the Saint Stephen Mausoleum in Székesfehérvár (1938). Here, Aba-Novák tackled themes central to Hungarian national identity and history, focusing on the life and legacy of Hungary's first Christian king. These murals further cemented his reputation as the preeminent muralist of his time in Hungary, capable of handling complex historical narratives with artistic power and technical mastery.

In his murals, Aba-Novák often employed what has been described as a "montage principle." This involved arranging distinct figural groups and narrative episodes within the larger composition in a way that maintained clarity and legibility, even amidst the overall dynamism. This approach, possibly influenced by contemporary cinema as well as historical precedents, allowed him to convey complex stories and ideas effectively on a grand scale. His murals are not merely decorations; they are powerful statements embedded in the public realm, reflecting the cultural and political concerns of interwar Hungary.

Artistic Circles, Connections, and Recognition

Throughout his career, Aba-Novák was an active participant in the Hungarian art scene. While perhaps not formally belonging to a single, rigidly defined group for his entire career, he was connected to various circles and movements. His time in the artists' colonies of Szolnok and Nagybánya placed him in contact with key trends in Hungarian modernism. The Nagybánya colony, founded by artists like Károly Ferenczy and János Thorma, was crucial in introducing plein-air painting and Post-Impressionist ideas to Hungary.

In Budapest, he associated with other leading artists. Sources mention an informal group or close association with István Szőnyi, another major figure in Hungarian painting known for his post-impressionist style and affiliation with the later "Gresham Circle" of artists. He also reportedly had connections with the avant-garde photographer André Kertész before Kertész emigrated. These interactions suggest Aba-Novák was engaged with the diverse artistic currents flowing through the Hungarian capital, from established modernists to those exploring newer media.

His relationship with other Hungarian modernists is complex. He emerged slightly later than the radical avant-garde group "The Eight" (Nyolcak), which included figures like Róbert Berény and Béla Czóbel, who had introduced Fauvism and Cubism to Hungary before WWI. While Aba-Novák certainly absorbed modernist principles, his style retained a stronger connection to figurative representation and narrative, particularly in his murals, distinguishing him from the more abstract or purely formal experiments of some earlier avant-gardists. He can be seen as bridging the gap between national traditions, the influence of earlier Hungarian modernists like József Rippl-Rónai (known for his Nabi connections), and contemporary European trends like Expressionism and the Novecento.

Aba-Novák's talent did not go unnoticed internationally. He exhibited abroad and received significant accolades. His crowning achievement in this regard came at the 1937 Paris International Exposition, where he was awarded two Grand Prizes for his contributions, likely including his mural work or designs. He also received awards at the prestigious Venice Biennale, further solidifying his international reputation. This recognition affirmed his status as a leading European artist of his generation.

From 1939 until his death, Aba-Novák also shared his knowledge and experience by teaching at the Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest, the same institution where he had begun his studies. This role allowed him to directly influence the next generation of Hungarian artists.

Anecdotes and Later Life

While historical records focus primarily on his artistic achievements, some anecdotal details offer glimpses into his life. One story suggests he worked for a time in a Budapest café, an experience that might have provided him with rich subject matter for observing everyday life, a theme prevalent in his genre paintings. Such experiences, common for artists needing to support themselves, often feed into their creative work in subtle ways.

His career, marked by intense productivity and growing recognition, was tragically cut short. Vilmos Aba-Novák died in Budapest in 1941 at the age of only 47. The exact circumstances are not always detailed in brief summaries, but his passing occurred as Europe was plunging deeper into the darkness of World War II, a conflict that would profoundly reshape the continent and the world he depicted.

Legacy and Influence

Vilmos Aba-Novák left an indelible mark on Hungarian art history. His primary legacy lies in his successful synthesis of diverse influences – Hungarian folk traditions, French modernism, Italian Novecento classicism, and Expressionist energy – into a unique and powerful artistic language. He demonstrated that modern art could embrace national identity without being parochial and engage with international trends without sacrificing individuality.

His mastery of monumental painting remains particularly significant. His murals in Szeged, Jászszentandrás, and Székesfehérvár are landmarks of 20th-century Hungarian public art. They showcase not only his technical skill in fresco and secco but also his ability to create compelling narratives on a grand scale, engaging with themes of history, faith, and collective memory. His innovative use of dynamic composition and the "montage principle" in these works offered new possibilities for mural art.

As a teacher at the Academy of Fine Arts, he directly influenced younger artists, although tracing specific stylistic lineages can be complex. His broader impact, however, is undeniable. He provided a powerful example of an artist who achieved both national prominence and international acclaim, working across different media – easel painting, graphic work, and monumental murals – with equal conviction.

His vibrant depictions of Hungarian life, particularly the energetic scenes of markets and circuses, continue to captivate viewers with their color and dynamism. While some interpretations of his work, particularly the state-commissioned murals, are viewed through the lens of the political climate of the Horthy era in Hungary, their artistic power remains evident. His work continues to be exhibited, studied, and appreciated. For instance, exhibitions featuring his work, such as one noted at the MODEM (Modern and Contemporary Arts Centre) in Debrecen in 2008, ensure his art remains accessible to new generations.

Compared to some of his international contemporaries, like the Austrian Expressionist Egon Schiele (with whom some sources suggest a tangential connection, perhaps through shared exhibitions or influences), Aba-Novák's work often maintained a stronger connection to narrative and a certain earthy vitality, especially in his genre scenes. His embrace of the Novecento's clarity in his murals contrasts with the more purely expressionistic or abstract paths taken by some other modernists.

Conclusion

Vilmos Aba-Novák was more than just a painter; he was a visual chronicler of his time and place, an innovator in technique, and a master of monumental scale. He navigated the complex artistic landscape of the early 20th century, drawing inspiration from diverse sources to create a body of work that is both distinctly Hungarian and part of the broader story of European modernism. From the intimate energy of his easel paintings to the epic scope of his murals, Aba-Novák's art continues to resonate with power, color, and a profound understanding of the human condition as expressed through the life and history of his nation. He remains a pivotal figure, essential for understanding the trajectory of Hungarian art in the modern era.