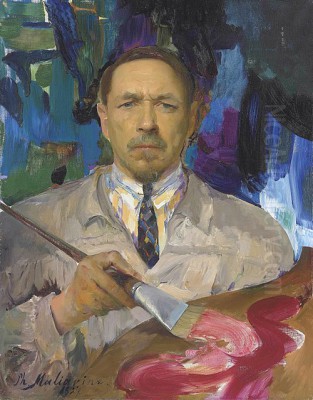

Filipp Andreevich Malyavin stands as a vibrant and somewhat enigmatic figure in the rich tapestry of Russian art. Born during a period of profound social and artistic change, he navigated the transition from the dominant Realism of the 19th century to the burgeoning Modernism of the early 20th century. A painter and draftsman of exceptional talent, Malyavin is celebrated primarily for his powerful, chromatically intense depictions of Russian peasant life, particularly women, rendered with an energy and boldness that often startled his contemporaries but secured his place in art history. His work pulses with the vitality, hardship, and spirit of the Russian countryside, captured through a unique stylistic synthesis that drew from tradition while embracing modern sensibilities.

From Peasant Roots to Artistic Aspirations

Filipp Malyavin's journey began on October 22, 1869, in the village of Kazanka, located in the Samara Governorate of the Russian Empire (present-day Orenburg Oblast). His origins were humble; he was born into a large, impoverished peasant family. This background profoundly shaped his artistic vision, providing him with an intimate understanding of the rural life that would become his most enduring subject. Despite the limitations of his circumstances, Malyavin displayed an early and undeniable passion for drawing and art.

Recognizing his talent, fellow villagers gathered funds to enable the young Malyavin to pursue his artistic inclinations. This led him, somewhat unconventionally, to the St. Panteleimon Monastery, a Russian Orthodox establishment on Mount Athos in Greece. There, between 1885 and 1891, he trained as an apprentice in the monastery's icon-painting workshop. This experience immersed him in the traditions of Byzantine art, its formal compositions, spiritual intensity, and distinct color palette. However, the strictures of religious iconography ultimately proved too confining for his burgeoning individualistic style.

The St. Petersburg Academy and the Influence of Repin

A pivotal moment occurred in 1891 when the sculptor Vladimir Beklemishev visited Mount Athos. Impressed by Malyavin's talent, Beklemishev recognized the young artist's potential beyond the confines of the monastery. He invited Malyavin to St. Petersburg, the vibrant cultural capital of Russia, opening the door to formal academic training. This marked a significant departure from the world of icon painting and thrust Malyavin into the heart of the Russian art establishment.

In 1892, Malyavin successfully enrolled as an auditor at the prestigious Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. Crucially, he entered the studio workshop of Ilya Repin, the undisputed leader of the Russian Realist movement and a towering figure in the nation's art scene. Studying under Repin provided Malyavin with rigorous training in drawing, anatomy, and composition, grounding his work in the strong technical foundation characteristic of the Academy. Repin's influence, particularly his mastery of psychological portraiture and large-scale historical canvases, was significant, yet Malyavin was already forging his own path.

Within Repin's dynamic studio, Malyavin worked alongside other talented students who would also achieve prominence, including Igor Grabar, a future painter, art historian, and museum director, and Konstantin Somov, who would become a key figure in the Mir Iskusstva movement. Another notable contemporary associated with Repin's circle, though slightly senior, was Valentin Serov, renowned for his insightful portraits. This environment fostered both collaboration and the development of distinct artistic personalities.

Forging a Unique Path: Color and Peasant Themes

While Malyavin absorbed the lessons of academic Realism under Repin, his artistic temperament yearned for greater expressive freedom. He began to deviate from the meticulous detail and narrative focus often associated with his teacher and the Peredvizhniki (Wanderers) movement, which Repin championed. Instead, Malyavin became increasingly fascinated by the expressive potential of pure, vibrant color and dynamic, broad brushwork.

His peasant background provided an inexhaustible source of inspiration. Unlike many Peredvizhniki artists who depicted peasants to highlight social injustice or illustrate ethnographic types, Malyavin approached his subjects with a different sensibility. He saw in them an elemental force, a raw vitality, and a deep connection to the Russian soil. His paintings, particularly of peasant women clad in brightly colored traditional sarafans and headscarves, became celebrations of this untamed energy. He was less interested in social commentary and more focused on capturing the visual splendor and psychological intensity of his subjects.

His developing style showed an awareness of contemporary European art movements, particularly Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, in its emphasis on light and color. The bold brushwork and expressive intensity also resonated with the emerging Fauvist and Expressionist currents, although direct influence is complex to trace. Some critics noted the influence of Scandinavian artists like Anders Zorn, known for his vigorous brushwork and depictions of rural life, whom Malyavin likely encountered through exhibitions or reproductions available in St. Petersburg.

Breakthrough and Controversy: "Laughter"

Malyavin's graduation work for the Academy in 1899, titled "Laughter" (Smekh), marked a definitive break and became a landmark piece. This large canvas depicts several peasant women, dressed in brilliant reds and other vibrant colors, seemingly caught in a moment of unrestrained, almost overwhelming, mirth against a green field. The painting explodes with color, dominated by swirling reds applied with broad, energetic strokes. The figures are not idealized; their faces are ruddy, their joy infectious yet almost primal.

The work proved highly controversial within the Academy. The Council was divided, with some professors, including Repin's rival Pavel Chistyakov, finding the work lacking in subject matter and refinement, deeming its raw energy and dazzling color inappropriate. Repin, however, fiercely defended his student's innovative vision. Despite the controversy, the painting was not awarded the customary gold medal for graduation, nor was Malyavin granted the title of "Artist," a significant setback at the time.

However, "Laughter" found triumphant vindication on the international stage. Exhibited at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) in Paris in 1900, the painting caused a sensation. Its boldness and vitality captivated the Parisian audience and critics. It was awarded a Gold Medal, catapulting Malyavin to international fame and silencing many of his detractors back home. The Luxembourg Museum in Paris acquired the painting, a testament to its perceived importance, although it later returned to Russia and is now housed in the State Russian Museum.

The Whirlwind of Peasant Life

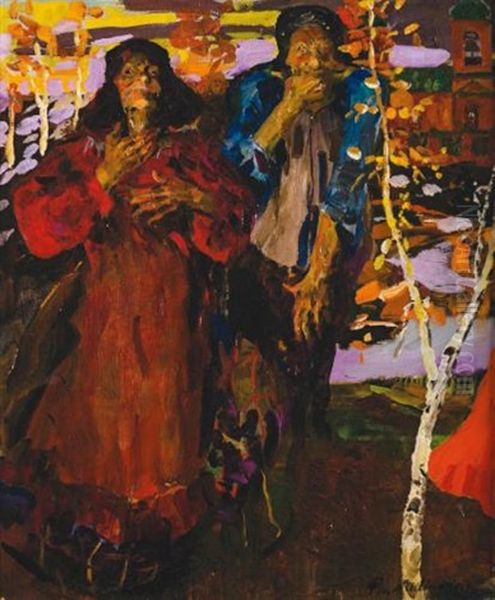

Following the success of "Laughter," Malyavin continued to explore the theme of peasant life with increasing confidence and stylistic audacity. His works from the early 1900s are characterized by an even greater emphasis on movement, color, and monumental scale. He often depicted groups of women, capturing the swirling motion of dance, the rhythm of rural festivals, or simply the vibrant presence of figures in the landscape.

One of his most famous works from this period is "Whirlwind" (Vikhr), painted in 1906. This dynamic composition portrays peasant women caught in an ecstatic, swirling dance. Their red dresses billow around them, merging with the energetic brushstrokes that define their forms and the surrounding space. The painting conveys an almost Dionysian frenzy, a powerful expression of collective energy and folk tradition. It transcends simple genre painting, becoming a symbol of the untamed spirit Malyavin perceived in the Russian peasantry.

Other significant works focusing on peasant women include "Three Women" (Tri Baby), also known as "Peasant Women," which presents robust figures with a monumental quality, and earlier pieces like "Peasant Girl Knitting a Stocking" (1895), which, while more restrained than his later works, already shows his interest in capturing the character and dignity of rural individuals. These paintings solidified his reputation as the preeminent painter of the Russian peasant woman, rendered not as a victim or an ethnographic specimen, but as a force of nature. His approach can be contrasted with contemporaries like Abram Arkhipov, another member of the Union of Russian Artists, whose depictions of peasant women, often in red, shared a vibrant palette but perhaps conveyed more pathos or focused on specific moments of labor or contemplation.

Navigating the Russian Art World: Mir Iskusstva and Exhibitions

Malyavin's rise coincided with a period of artistic ferment in Russia. While rooted in the Realist tradition through his training, his bold style aligned him more closely with the younger generation seeking new forms of expression. He became associated with the influential "Mir Iskusstva" (World of Art) movement, although his relationship with the group was complex. Mir Iskusstva, led by figures like Alexandre Benois, Léon Bakst, and the impresario Sergei Diaghilev, championed aestheticism, artistic synthesis, and a revival of interest in 18th-century art and theatrical design, often contrasting with the social concerns of the Peredvizhniki.

While Malyavin exhibited with Mir Iskusstva, his earthy, robust peasant themes differed significantly from the refined, often nostalgic or fantastical subjects favored by core members like Benois or Konstantin Somov. However, the movement's embrace of individualism and stylistic diversity provided a platform for Malyavin's unique vision. He was also closely involved with the Union of Russian Artists, a Moscow-based exhibiting society formed in 1903, which brought together many former Peredvizhniki members and younger artists, including figures like Konstantin Korovin, Valentin Serov (who bridged several groups), Mikhail Vrubel (a unique Symbolist figure), Nicholas Roerich, and Boris Kustodiev. Malyavin regularly participated in their exhibitions, showcasing his latest works to the Russian public.

His international reputation, secured by the Paris success, continued to grow. His works were shown in Venice, Rome, Berlin, and other European capitals. He gained recognition as a distinct voice in Russian art, one who combined national themes with a modern, expressive technique. His friend and colleague, the Ukrainian-born painter Alexander Murashko, who also studied with Repin, similarly navigated the currents of Realism and Modernism, though with a different stylistic outcome.

Portraiture and Later Works

Beyond his iconic peasant scenes, Malyavin was also a highly skilled portraitist. His training under Repin had equipped him with the ability to capture not only a physical likeness but also the psychological depth of his sitters. He painted portraits of family members, fellow artists, and prominent figures of the time. His portrait style often retained the vigorous brushwork and rich color of his peasant paintings, lending them a particular dynamism.

After the 1917 Revolution, Malyavin initially remained in Russia. He even reportedly created sketches or portraits of Bolshevik leaders, including Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky, although the exact circumstances and extent of these works are sometimes debated, particularly whether they were done from life sittings. He engaged in some state-organized activities, serving on commissions and briefly teaching. However, his individualistic style and focus on peasant themes, which could be interpreted as celebrating an older, pre-revolutionary Russia, did not always align with the evolving artistic doctrines of the new Soviet state, particularly the later push towards Socialist Realism.

Emigration and Final Years

Feeling increasingly constrained by the changing political and artistic climate in Russia, Malyavin made the decision to leave the country. In 1922, he and his family emigrated, settling first in Paris. France became his primary base for the remainder of his life, although he continued to travel and exhibit his work internationally, including shows in various European cities.

In exile, Malyavin continued to paint, often revisiting the Russian peasant themes that had defined his career. While some critics perceive a shift in mood or intensity in his later works compared to the explosive energy of his pre-revolutionary canvases, his commitment to his core subjects and signature style remained evident. He produced numerous portraits and drawings during this period as well. He maintained a presence in the European art scene, participating in exhibitions and finding patrons for his work.

His final years were overshadowed by the outbreak of World War II. He was living in Nice, in the South of France, when he died on December 23, 1940. Some accounts mention difficulties during the war, including potential arrest or interrogation by occupying forces (sources sometimes mention Brussels during an earlier period), which may have contributed to hardship in his last months, but he died in Nice. His death occurred far from the Russian soil that had so deeply inspired his art.

Legacy and Influence

Filipp Malyavin left an indelible mark on Russian art. His unique contribution lies in his powerful and vibrant interpretation of peasant life, elevating it beyond genre painting to a level of monumental, expressive art. He demonstrated that traditional Russian themes could be explored through a modern artistic language, characterized by bold color, dynamic composition, and energetic brushwork.

His work serves as a fascinating bridge between the 19th-century Realism of his teacher, Ilya Repin, and the modernist experiments of the early 20th century. While associated with movements like Mir Iskusstva and the Union of Russian Artists, his style remained highly individual, resisting easy categorization. He influenced subsequent generations of Russian artists interested in national themes and expressive techniques.

Today, Malyavin's major works are held in prestigious collections, primarily in Russia at the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, as well as in numerous regional museums. His paintings continue to captivate viewers with their sheer visual force and their profound connection to the spirit of the Russian land and its people. He remains celebrated as a master colorist and a painter who captured the raw, untamed energy of rural Russia like few others. His life story, from humble peasant origins to international acclaim and eventual exile, reflects the dramatic historical and artistic transformations of his era.