Frederic Sackrider Remington stands as one of the most significant and recognizable figures in American art history. Primarily known for his dynamic and evocative depictions of the American West, Remington was a painter, illustrator, sculptor, and writer whose work captured the closing moments of the 19th-century frontier. His images of cowboys, Native Americans, cavalry soldiers, and rugged landscapes have profoundly shaped the popular imagination of the Old West, creating archetypes that endure to this day. This article explores the life, career, artistic evolution, and lasting legacy of this pivotal American artist.

Early Life and Formative Years

Frederic Sackrider Remington was born on October 4, 1861, in Canton, New York. He was the only child of Seth Pierpont Remington and Clara Bascom Sackrider. His father was a respected figure, a Union cavalry officer during the Civil War who later became a newspaper publisher and postmaster. This paternal connection to the military, particularly the cavalry, likely planted early seeds of interest in the subjects that would later dominate Remington's art.

Growing up in upstate New York, young Frederic was an active and robust child. He enjoyed outdoor pursuits like swimming, fishing, hunting, and especially riding horses – an activity that would become central to his artistic vision. He was reportedly indulged by his parents and developed an early passion for sketching, often drawing soldiers and cowboys even as a boy. His formal education began at the Essex Institute, a local school in Canton.

Remington's father hoped his son might pursue a military career, and Frederic briefly attended the Highland Military Academy in Worcester, Massachusetts. However, academics were not his strong suit, and he did not graduate. Instead, his artistic inclinations led him to enroll in the newly established School of Fine Arts at Yale University in 1878. He studied there for less than two years, focusing on drawing and painting under instructors like John Henry Niemeyer. While at Yale, he found more success on the football field as a player than in his formal art studies, though the foundational training was undoubtedly valuable.

His time at Yale was cut short by the death of his father in 1880. Remington left university without a degree and, after a brief stint clerking in Albany, New York, used a modest inheritance to chase a dream that had been brewing for years: to see the American West for himself.

The Call of the West and Early Ventures

In 1881, at the age of 19, Remington made his first journey west, traveling to Montana. He harbored romantic notions of making his fortune, perhaps as a rancher or prospector. He tried his hand at various ventures, including investing in a sheep ranch near Peabody, Kansas, and later operating a hardware store and a saloon in Kansas City. These business attempts proved unsuccessful, highlighting his lack of aptitude for commerce but providing invaluable firsthand experience of Western life.

During these early years in the West, Remington wasn't yet a professional artist, but he was constantly observing and sketching the people, animals, and landscapes around him. He encountered cowboys, ranchers, soldiers, and Native Americans, absorbing the atmosphere, the dialects, and the raw energy of the frontier. He saw the vastness of the plains, the harshness of the climate, and the unique character forged by life in such an environment.

Though his business ventures failed, these experiences were transformative. They stripped away some of the Eastern romanticism about the West and replaced it with a more grounded, albeit still dramatic, understanding. He realized that the West he was witnessing – the era of the open range, the Indian Wars, and the dominance of the horse – was rapidly changing and disappearing. This sense of urgency fueled his desire to document it. A turning point came when Harper's Weekly, a major illustrated magazine, accepted and published one of his sketches (redrawn by a staff artist) in 1882. This small success hinted at a potential path forward.

Forging an Artistic Identity: The Illustrator

Returning East in 1884, Remington married his sweetheart, Eva Caten, whom he had met before his Western sojourn. Initially, Eva's father had reservations due to Remington's lack of stable prospects, but the marriage proceeded. The couple settled briefly in Kansas City before Remington's business failures prompted a return to New York City in 1885. Determined now to make a living as an artist, he began seriously pursuing illustration work.

He enrolled briefly at the Art Students League of New York in 1886, refining his technique. Armed with his portfolio of Western sketches and a growing understanding of the market, Remington began submitting his work to magazines like Harper's Weekly, Outing, and The Century Magazine. His timing was perfect. Public fascination with the West was high, fueled by dime novels and Wild West shows, and illustrated magazines were booming.

Remington's illustrations stood out for their authenticity, dynamism, and narrative power. Unlike many artists depicting the West from studios based on photographs or imagination, Remington drew from his own observations. His figures were not static poses but captured in motion – horses bucking, cowboys riding hard, soldiers in skirmishes. His detailed, linear style was well-suited for reproduction in print. He quickly gained recognition, and by the late 1880s, he was one of the most sought-after illustrators in America, commanding high fees. His work appeared alongside stories by prominent writers, including Theodore Roosevelt, who became a friend and admirer.

Mastering the Mediums: Painting and Sculpture

While illustration provided financial stability and widespread fame, Remington aspired to be recognized as a fine artist. He began producing oil paintings, often based on his illustrations or Western trips, submitting them to exhibitions at prestigious venues like the National Academy of Design. His paintings retained the energy and narrative focus of his illustrations but allowed for greater exploration of color, light, and atmosphere.

One of his early major paintings, A Dash for the Timber (1889), exemplifies his dramatic style. It depicts a group of cowboys frantically riding towards a patch of woods, pursued by Native American warriors. The painting is a whirlwind of motion, dust, and desperation, showcasing Remington's skill in rendering horses and figures in complex action poses. It was exhibited at the National Academy and received critical acclaim, solidifying his reputation as a serious painter.

In the mid-1890s, Remington ventured into another medium: sculpture. Feeling that he could express the dynamic action of his subjects even more effectively in three dimensions, he began experimenting with clay. His first bronze sculpture, The Bronco Buster (1895), was an immediate sensation. Depicting a cowboy mastering a wildly bucking horse, the sculpture captured a moment of intense energy and precarious balance. It was technically innovative, utilizing the lost-wax casting process to achieve intricate detail and dynamic composition, with the horse seemingly suspended in mid-air.

The Bronco Buster became an iconic image of the West and remains one of Remington's most famous works. He followed it with other successful bronzes, such as The Cheyenne and The Scalp, further exploring themes of conflict, survival, and mastery over nature. His sculptures, like his paintings and illustrations, emphasized action and authenticity, setting him apart from the more staid, classical traditions of sculpture prevalent at the time. His work in bronze invited comparisons, in terms of capturing movement, perhaps to European innovators like Auguste Rodin, though their subjects and aesthetics were vastly different.

Evolution of Style: Impressionism and Nocturnes

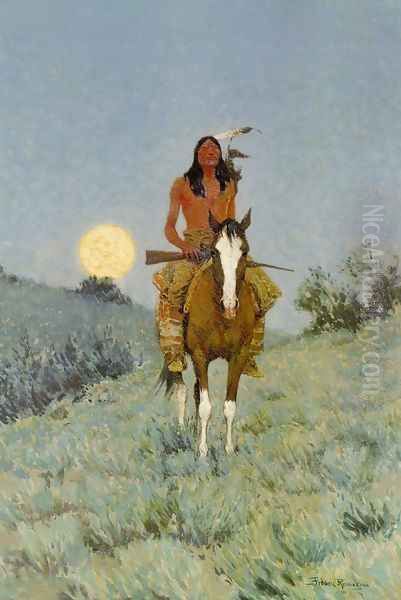

As Remington matured as an artist, his style continued to evolve. While his early work was characterized by sharp detail and a clear narrative line, influenced by his illustration background, his later paintings showed a marked shift towards a looser, more painterly technique. He became increasingly interested in the effects of light and color, moving away from strict realism towards a more atmospheric and evocative approach.

This change was partly influenced by his exposure to Impressionism. Although Remington publicly expressed disdain for some modern art trends, the work of French Impressionists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, with their focus on capturing fleeting moments of light and color, seems to have resonated with him. He began experimenting with brighter palettes and broken brushwork, particularly in his depictions of the harsh sunlight and open landscapes of the West. American Impressionists such as Childe Hassam and Theodore Robinson were contemporaries exploring similar concerns with light, though Remington applied these ideas to uniquely American subjects.

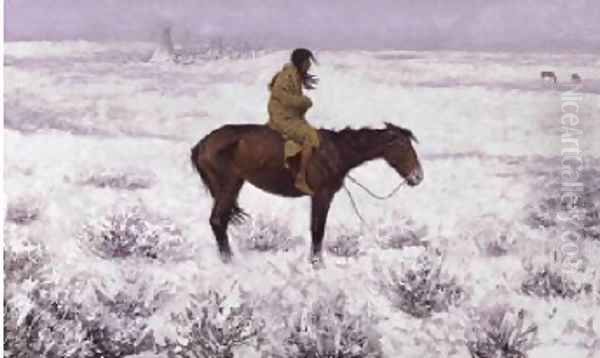

In the final decade of his life, Remington embarked on a significant exploration of nocturnes – scenes set at night or twilight. He became fascinated with the challenge of painting darkness and moonlight, experimenting with limited palettes, often dominated by blues, greens, and grays. These later works, such as those featured in his 1907 exhibition "The Color of Night," are often more moody, introspective, and symbolic than his earlier action scenes. They convey a sense of mystery, solitude, and sometimes melancholy, perhaps reflecting his awareness of the vanishing frontier he had spent his life documenting. These nocturnes share a certain atmospheric quality with the night paintings of James McNeill Whistler, though Remington's subjects remained rooted in the Western narrative.

Themes and Subjects: The Vanishing Frontier

Throughout his career, Remington's primary subject matter remained the American West, but his focus shifted over time, reflecting both his artistic development and the historical changes occurring on the frontier. His core themes included:

The Cowboy: Remington's cowboys are iconic – rugged, independent figures battling the elements, mastering wild horses, or engaging in range work. Works like The Bronco Buster and The Fall of the Cowboy (1895), the latter depicting cowboys dealing with the new reality of barbed wire fences, capture both the romantic ideal and the encroaching end of the open-range era.

The Cavalry Soldier: Drawing perhaps on his father's legacy and his own observations at frontier posts, Remington frequently depicted the U.S. Cavalry. His soldiers are often shown in action – patrolling, skirmishing with Native Americans, or enduring harsh conditions. These works often carry a heroic tone.

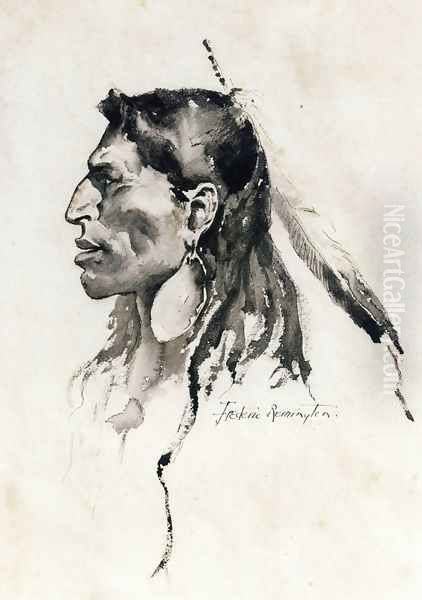

Native Americans: Remington's portrayal of Native Americans is complex and has drawn criticism for sometimes relying on stereotypes prevalent in his time, depicting them as hostile adversaries in works like A Dash for the Timber. However, he also created more nuanced images, particularly later in his career, showing aspects of their daily life and dignity, possibly influenced by friendships like the one with cavalry officer Powhatan Henry Clarke, who had deep connections with Indigenous communities. His approach contrasts with the earlier, more ethnographic focus of George Catlin or the later, often more romanticized views of the Taos Society artists like Joseph Henry Sharp or E. Irving Couse.

The Landscape: The Western landscape itself was a crucial element in Remington's work – vast, unforgiving, and beautiful. It served not just as a backdrop but as an active force shaping the lives of the figures within it. His later nocturnes, in particular, emphasize the power and mystery of the natural world.

Action and Conflict: Movement and struggle are central to Remington's art. Whether it's a horse fight, a stampede, or a military engagement, his compositions are typically charged with energy and tension. This focus on action set him apart from earlier Western landscape painters like Albert Bierstadt or Thomas Moran, whose work emphasized grandeur and serenity.

The End of an Era: Underlying much of Remington's work is a sense of nostalgia and an awareness that the Wild West he knew was disappearing due to settlement, technology (like barbed wire and railroads), and the subjugation of Native American tribes. His art serves as both a celebration and an elegy for a bygone era.

Remington and His Contemporaries

Frederic Remington operated within a vibrant artistic landscape, both in the specialized field of Western art and in the broader American art scene. His most significant contemporary and sometimes rival in depicting the West was Charles M. Russell. While both artists tackled similar subjects, their backgrounds and perspectives differed. Remington, an Easterner educated at Yale, approached the West initially as an observer and illustrator, achieving fame relatively quickly through publications. Russell, by contrast, lived much of his life in Montana, working as a cowboy for years before gaining recognition as an artist.

Their portrayals also diverged. Remington's work often focused on dramatic conflict and action, sometimes reflecting the prevailing biases of the era regarding Native Americans. Russell, having lived more closely with Western life and Native American communities, often depicted scenes with greater empathy towards Indigenous peoples and a focus on the daily rhythms of cowboy life, rather than just high drama. While Remington's career was largely centered in the East and tied to publishing, Russell later developed connections with the burgeoning film industry in Hollywood. Despite these differences and a degree of professional rivalry, both artists are considered giants of Western American art.

Beyond Russell, Remington's contemporaries included the Taos Society artists (Sharp, Couse, Oscar E. Berninghaus, etc.), who focused on the Pueblo cultures of New Mexico, and painters like Maynard Dixon, known for his modernist interpretations of the Western landscape. In the illustration world, he competed with talents like Howard Pyle and A.B. Frost. His work can also be seen in the context of American artists like Winslow Homer, who shared an interest in depicting rugged masculinity and outdoor life, albeit primarily in Eastern settings.

A Complex Lens: Depicting Native Americans

Remington's portrayal of Native Americans remains a subject of discussion and critique. Many of his illustrations and paintings, particularly earlier ones commissioned for magazines hungry for sensationalism, depict Native Americans as antagonists – fierce warriors engaged in conflict with cowboys or soldiers. These images often reflected and reinforced the stereotypes and racial prejudices common in late 19th-century America. Titles like Captured or scenes of ambush catered to a public perception of Native Americans as inherently hostile.

However, his body of work is not monolithic. Remington also produced images that depicted Native Americans with a degree of dignity, focusing on their horsemanship, ceremonies, or resilience in the face of change. His friendship with Powhatan Henry Clarke, an officer knowledgeable about and sympathetic to certain tribes, may have offered him alternative perspectives. Some later works show a greater interest in ethnographic detail or a more somber mood, hinting at the tragic consequences of westward expansion for Indigenous peoples.

It is crucial to view Remington's work within its historical context while acknowledging the problematic nature of some of his representations. He was a man of his time, and his art reflects the complex and often contradictory attitudes of that era towards Native Americans. His legacy includes both perpetuating harmful stereotypes and creating powerful images that, intentionally or not, documented the presence and struggles of Indigenous peoples during a period of profound upheaval.

Beyond the Canvas: Remington as Author and Correspondent

Remington's creative output was not limited to visual art. He was also a capable writer, publishing several books and numerous articles, often illustrated with his own drawings. His writing style was direct, anecdotal, and infused with the vernacular of the West. His notable books include Pony Tracks (1895), a collection of articles and stories about his Western experiences; Drawings (1897), a portfolio of his illustrations; and Crooked Trails (1898), another collection of stories and sketches.

His writing provided further insight into his views on the West, adventure, and the characters he encountered. It complemented his visual art, offering narratives and reflections that added depth to his depictions. Like his artwork, his writing captured the spirit of the frontier, though sometimes also reflecting the biases of his time.

In 1898, Remington's adventurous spirit led him to serve as a war artist and correspondent during the Spanish-American War. He traveled to Cuba with fellow journalists like Richard Harding Davis and Stephen Crane, documenting the conflict for William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal and for Harper's Weekly. While his illustrations of the war were initially popular, the experience of witnessing modern warfare firsthand reportedly left him disillusioned. Some accounts suggest this experience contributed to the darker, more introspective mood found in some of his later work.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

Frederic Remington's influence on American culture has been immense and enduring. More than perhaps any other artist, he defined the visual iconography of the American West. His images of lean cowboys, charging cavalry, bucking broncos, and stoic Native Americans became deeply ingrained in the national consciousness. They provided a visual vocabulary for the myth of the West – a narrative of adventure, individualism, conflict, and the taming of a wild frontier.

His work reached a vast audience through popular magazines, making him a household name during his lifetime. This widespread dissemination meant his vision of the West became the dominant one for generations. His influence extended beyond illustration and painting into popular culture. Early Western films often drew visual inspiration directly from Remington's compositions. Writers like Owen Wister, author of The Virginian (often considered the first modern Western novel), and Remington's friend Theodore Roosevelt shared and promoted a similar vision of Western life and masculine virtue. Even later writers like Ernest Hemingway, known for his own distinct style, arguably absorbed elements of the rugged, adventurous masculinity that Remington helped codify.

Today, Remington's works are highly sought after by collectors and are prominently featured in major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Art Institute of Chicago, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, and, of course, the Frederic Remington Art Museum in Ogdensburg, New York, near his childhood home. His sculptures, particularly The Bronco Buster, remain instantly recognizable symbols of the American West.

Final Years and Enduring Presence

In the early 1900s, Remington sought a quieter life away from the bustle of New York City. He purchased an estate in Ridgefield, Connecticut, where he built a new studio and continued to paint prolifically, focusing increasingly on his nocturnes and experimenting with his technique. He enjoyed considerable success and financial security, having achieved fame in multiple fields.

However, his robust lifestyle and considerable weight gain began to take a toll on his health. In December 1909, he suffered an attack of appendicitis. An emergency appendectomy was performed, but complications arose. Frederic Remington died on December 26, 1909, at the relatively young age of 48. His sudden death cut short a career that was still evolving.

Despite his relatively short life, Frederic Remington left behind an enormous body of work – estimated at over 3,000 paintings and drawings, and 22 bronze sculptures. His legacy is multifaceted. He was a master draftsman, a dynamic painter, an innovative sculptor, and a vivid chronicler of a pivotal era in American history. While contemporary perspectives rightly challenge some aspects of his work, particularly his depictions of Native Americans, his artistic skill and his profound impact on shaping the enduring myth of the American West remain undeniable. He captured the energy, the conflict, and the fading light of the frontier like no other artist.