Antonio Mancini stands as a fascinating and somewhat enigmatic figure in the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century European art. An Italian painter whose life was marked by both prodigious talent and significant personal struggle, Mancini forged a unique path, blending the tenets of Italian Realism (Verismo) with influences from French Impressionism and developing highly individualistic, texturally rich techniques. His powerful portraits, often depicting the humble and marginalized, as well as society figures and searching self-portraits, earned him admiration from contemporaries like John Singer Sargent, yet his name remains less universally recognized than some of his peers. This exploration delves into the life, art, and legacy of a painter whose work resonates with raw emotion, technical brilliance, and profound humanity.

Early Life and Neapolitan Foundations

Antonio Mancini was born in Rome in 1852. However, his formative artistic years were spent in Naples, a vibrant and crucial center for Italian art in the 19th century. Demonstrating exceptional artistic aptitude from a very young age, Mancini was admitted to the Naples Academy of Fine Arts (Accademia di Belle Arti di Napoli) at the remarkably early age of twelve. This precocious talent immediately placed him under the tutelage of some of the leading figures of the Neapolitan school.

His primary mentors at the Academy were Domenico Morelli (1826-1901) and Filippo Palizzi (1818-1899). These two artists represented different, yet complementary, facets of Italian painting. Morelli, a leading figure in Italian Romantic Realism, was known for his historical and literary subjects, dramatic compositions, and rich, often dark, color palette. He encouraged Mancini's expressive potential and likely influenced his sense of drama and psychological depth. Palizzi, conversely, was a staunch advocate of Naturalism, emphasizing direct observation from life and meticulous rendering. His influence instilled in Mancini a rigorous discipline and a commitment to capturing the tangible reality of his subjects.

During his studies, Mancini also associated with Francesco Paolo Michetti (1851-1929), another highly talented painter slightly older than him, who became a lifelong friend. Michetti, known for his vibrant depictions of Abruzzese folk life, shared Mancini's interest in realist themes. The Neapolitan environment, with its blend of academic tradition, realist impulses, and burgeoning interest in light and color, provided a fertile ground for Mancini's development. He quickly absorbed the lessons of his teachers, mastering technique while already hinting at a distinctive personal vision. He also became friendly with the sculptor Stanislao Lista (1824-1908), another figure within the Neapolitan artistic milieu.

Verismo and the Depiction of Humble Lives

Mancini emerged as an artist during the ascendancy of Verismo in Italian art and literature. Analogous to French Realism associated with artists like Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), Verismo sought to portray contemporary life and society with unvarnished truthfulness, often focusing on the lives of the working class, the poor, and the marginalized. Mancini became one of the movement's most compelling visual proponents. His early works frequently depicted the street children (scugnizzi), circus performers (saltimbanchi), musicians, and artisans who populated the bustling streets of Naples.

These were not sentimentalized portrayals but rather deeply empathetic studies imbued with a sense of dignity and psychological presence. Works like Lo Scugnizzo (The Street Urchin, c. 1870s) and The Poor Schoolboy (Il Povero Scolaro, 1876), now housed in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, exemplify this phase. They showcase his early mastery of chiaroscuro – the dramatic interplay of light and shadow – learned partly from Morelli, combined with Palizzi's emphasis on realistic detail. The brushwork is already confident and expressive, capturing the textures of worn clothing and the poignant expressions of his young subjects.

His talent gained recognition quickly. As early as 1872, he exhibited two paintings at the prestigious Paris Salon, signaling his ambition beyond Italy. Throughout the 1870s, he continued to exhibit successfully in Naples, Rome, Turin, and Venice, establishing his reputation as a leading figure among the younger generation of Italian realists. His works from this period, such as Dopo il duello (After the Duel, 1872), further demonstrated his ability to handle complex compositions and convey narrative tension.

Parisian Encounters and Impressionist Echoes

Like many ambitious European artists of his time, Mancini was drawn to Paris, the undisputed center of the avant-garde art world. He spent significant periods there, particularly in the mid-to-late 1870s. These visits proved transformative, exposing him to new artistic currents, most notably Impressionism. In Paris, he encountered leading figures of the movement, including Edgar Degas (1834-1917) and Édouard Manet (1832-1883).

While Mancini never fully adopted the Impressionist aesthetic – his commitment to solid form and psychological depth remained paramount – the exposure undeniably impacted his work. His palette began to brighten, incorporating more vibrant colors and exploring the effects of light with greater intensity. His brushwork became looser and more broken in places, adding a new layer of dynamism to his surfaces. He absorbed the Impressionists' interest in capturing fleeting moments and modern life, though he filtered these concerns through his own Verismo lens, maintaining a focus on the individual character and social context of his subjects.

His time in Paris also brought him into contact with international art dealers like Goupil & Cie, which helped to introduce his work to a wider audience. He formed crucial connections with fellow artists and patrons who would become important supporters throughout his often-difficult career. This period marked a broadening of his artistic horizons, integrating French avant-garde ideas with his strong Italian realist foundations.

Technical Innovation and Mature Style: The Graticola and Impasto

As Mancini matured, he developed a highly unconventional and distinctive painting technique that set him apart even from his innovative contemporaries. Central to his method, particularly from the 1880s onwards, was the use of the graticola. This was a grid made of strings, placed both in front of the sitter and on the canvas itself. By viewing the subject through the grid, Mancini could accurately transfer proportions and compositional elements, segment by segment. This methodical approach allowed him a framework upon which he could build his increasingly complex and textured surfaces. Often, traces of this grid remain visible in the finished paintings, becoming an integral part of their structure.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Mancini's mature style is his radical use of impasto. He applied paint incredibly thickly, often directly from the tube, sculpting it on the canvas with brushes, palette knives, and even his fingers. This resulted in surfaces of extraordinary textural richness, where the paint itself possesses a physical, almost three-dimensional presence. The thick layers capture and reflect light in unique ways, enhancing the vibrancy and immediacy of the image.

Furthermore, Mancini experimented boldly with materials. In his later works, particularly from the early 20th century, he began incorporating pieces of reflective material directly into the paint surface – fragments of glass, tin foil, or metal – to create dazzling highlights and enhance the sense of luminosity. This practice, while eccentric, underscores his relentless search for ways to intensify the visual impact and material reality of his paintings. Works like Il Votante (The Votary, c. 1880s) showcase this intense focus and developing textural complexity.

Recognition, Relationships, and Patronage

Despite his unconventional methods and often challenging subject matter, Mancini achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime, particularly among fellow artists and discerning collectors. His most famous admirer was the celebrated American expatriate portraitist John Singer Sargent (1856-1925). Sargent encountered Mancini's work, likely in Paris or London, and was profoundly impressed. He famously declared Mancini to be the greatest living painter, a remarkable endorsement from an artist of Sargent's stature. Sargent not only praised Mancini but also actively promoted his work, purchasing several paintings himself and encouraging his own patrons to do the same. This friendship provided Mancini with crucial support and validation on the international stage.

Another significant supporter was the Dutch marine painter and collector Hendrik Willem Mesdag (1831-1915). Mesdag, a prominent figure in the Hague School, acquired a substantial number of Mancini's works, which later formed part of the collection of The Mesdag Collection museum in The Hague. This patronage was vital, especially during periods of financial hardship for Mancini.

Mancini also maintained connections within the Italian and international art scenes. While perhaps not as socially integrated as contemporaries like Giovanni Boldini (1842-1931) or Giuseppe De Nittis (1846-1884), who achieved great success painting fashionable society, Mancini's sheer talent commanded respect. His work was exhibited alongside theirs and other prominent artists like James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) in international exhibitions. His early career was also aided by patrons like the Belgian aristocrat Albert Cahen, who facilitated his first Paris exhibition. The Spanish virtuoso Mariano Fortuny (1838-1874), whose brilliant technique captivated Rome and Paris before his early death, was another contemporary whose work Mancini would have known.

A Life of Struggle: Mental Health and Financial Instability

Mancini's artistic triumphs were shadowed by significant personal difficulties. He suffered from periods of severe mental illness, leading to his hospitalization in a Naples mental institution in 1881. While he eventually recovered enough to resume his career, these psychological struggles seem to have recurred throughout his life, contributing to erratic behavior and periods of instability. His letters and contemporary accounts sometimes hint at a volatile temperament and profound anxieties.

These mental health challenges were often compounded by persistent financial insecurity. Despite the admiration of figures like Sargent and Mesdag, and periods of successful sales, Mancini frequently found himself in precarious financial situations. He relied heavily on the support of friends, patrons, and dealers to survive. His unconventional working methods and sometimes difficult personality may have hindered his ability to secure consistent, lucrative portrait commissions compared to more conventional society painters.

This combination of psychological fragility and economic hardship undoubtedly impacted his life and work. Some critics have suggested that the intense, almost obsessive quality of his later paintings, with their thick impasto and embedded materials, might reflect his inner turmoil. Yet, remarkably, he continued to produce powerful and innovative art throughout these challenging decades, demonstrating extraordinary resilience and an unwavering dedication to his craft.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

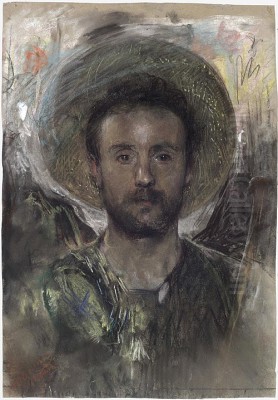

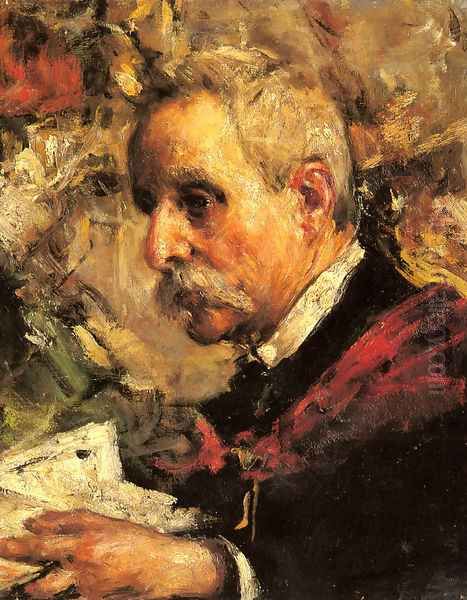

After periods spent in Naples, Paris, and London, Mancini eventually settled primarily in Rome and later in nearby Frascati during the early 20th century. The period following World War I seems to have brought him a greater degree of stability and recognition within Italy. He continued to paint portraits, including numerous searching self-portraits that offer intimate glimpses into his psyche during his later years. Works like Self-Portrait (c. 1920s) and the portrait of Marchese Giorgio Capranica del Grillo (c. 1920s) show a continuation of his signature style, perhaps with a slightly more subdued mood but retaining the characteristic textural richness and psychological insight.

Antonio Mancini died in Rome in 1930. While his fame may have been eclipsed internationally by the rise of Modernist movements like Cubism and Futurism, his unique contribution to painting remains significant. He stands as a crucial bridge figure, deeply rooted in the 19th-century realist tradition but pushing its boundaries through his radical techniques and expressive intensity, anticipating aspects of 20th-century Expressionism.

His works are held today in major museums across the world, including the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna in Rome, the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples, the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, The Mesdag Collection in The Hague, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Vatican Museums. His paintings continue to fascinate viewers with their raw emotional power, dazzling technical virtuosity, and profound empathy for the human condition.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several key works encapsulate Mancini's artistic journey and unique style:

Lo Scugnizzo (The Street Urchin, c. 1870s): An early masterpiece of Verismo, depicting a young Neapolitan street boy with striking realism and empathy. It showcases his early command of form and chiaroscuro.

The Poor Schoolboy (Il Povero Scolaro, 1876): Housed in the Musée d'Orsay, this painting captures the melancholic dignity of a young student, rendered with sensitivity and detailed observation typical of his early realist phase.

Dopo il duello (After the Duel, 1872): An example of his ability to handle narrative and dramatic tension, reflecting the influence of Domenico Morelli's historical paintings but applied to a contemporary (though perhaps staged) scene.

Il Votante (The Votary, c. 1880s): This work exemplifies his mature style, with its intense psychological focus, dramatic lighting, and increasingly thick application of paint, possibly reflecting the period after his initial mental health crisis.

Self-Portraits (Various dates, especially later): Mancini painted numerous self-portraits throughout his life. The later examples are particularly compelling, often showing him confronting the viewer with a searching, intense gaze, the paint applied with characteristic thickness and complexity, serving as intimate records of his physical and psychological state.

Portrait of the Artist's Father (c. 1875): An early example of his portraiture skills, demonstrating his ability to capture character and likeness with sensitivity even before his most radical technical developments.

These works, among many others, demonstrate the evolution of Mancini's style, from the disciplined realism of his Neapolitan training through his engagement with Impressionism to the highly personal and texturally extreme techniques of his maturity.

Conclusion: A Singular Vision

Antonio Mancini remains a compelling figure in art history, an artist who defies easy categorization. He was a master of Realism, deeply invested in capturing the world around him, particularly the lives of the less fortunate. Yet, he was also a relentless innovator, pushing the material possibilities of paint to create surfaces of astonishing complexity and expressive power. His encounters with French Impressionism broadened his palette and approach to light, but he integrated these influences into a vision that remained distinctly his own, marked by psychological intensity and a profound connection to his subjects.

His life, fraught with mental and financial challenges, stands as a testament to artistic resilience. Despite these obstacles, he produced a body of work that impressed some of the greatest artists of his time and continues to resonate today. Mancini's paintings offer a unique window into late 19th and early 20th-century Italy, but more importantly, they speak to universal human experiences of struggle, dignity, and the enduring power of the individual spirit, all conveyed through a singular, unforgettable artistic language. He remains a master whose work rewards close looking and deeper understanding.