Virginie Élodie Marie Thérèse Demont-Breton stands as a significant figure in late 19th and early 20th-century French art. Born on July 26, 1859, in Courrières, Pas-de-Calais, and passing away on January 10, 1935, in Paris, she was not only a prolific and celebrated painter associated with the Naturalist movement but also a fervent advocate for the rights and recognition of women artists. Her life and career offer a compelling insight into the artistic currents of her time and the societal challenges faced by women aspiring to professional artistic careers. Her legacy is marked by poignant depictions of maternal love, the arduous lives of fishing communities, and a steadfast commitment to advancing the cause of her fellow female artists.

An Artistic Heritage: The Breton Family Influence

Virginie Demont-Breton was immersed in art from her earliest moments. She was the daughter of Jules Breton (1827-1906), one of the most renowned French painters of rural life and peasant scenes, a leading figure of Realism and Naturalism. Her uncle, Émile Breton (1831-1902), was also a respected landscape painter, known for his dramatic and often melancholic depictions of coastal and winter scenes. This familial environment provided Virginie with an unparalleled artistic upbringing. She grew up surrounded by discussions of art, observing her father at work, and absorbing the principles of academic technique and the burgeoning interest in portraying everyday life with truthfulness and empathy.

Jules Breton's influence on his daughter was profound. He was her first and most important teacher, guiding her early artistic endeavors and instilling in her a respect for craftsmanship and a keen observational skill. His own success in the Paris Salon and his international reputation provided Virginie with both a model to aspire to and connections within the art world that would prove invaluable. Unlike many aspiring female artists of her time who struggled for access to formal training, Virginie benefited from direct tutelage within a highly accomplished artistic household. This early exposure undoubtedly shaped her thematic interests, particularly her focus on figures within landscape settings and her sympathetic portrayal of working-class subjects.

Formative Years and Mentorship: Rosa Bonheur's Guiding Hand

While her father laid the foundational stones of her artistic education, Virginie Demont-Breton also found a powerful mentor and role model in Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899). Bonheur was an icon of female artistic success in the 19th century, an acclaimed animalier (animal painter) who had achieved international fame and financial independence through her art, a rare feat for a woman of her era. Known for works like The Horse Fair (1852-55), Bonheur was a symbol of female empowerment, having even obtained official permission to wear men's attire to facilitate her work in stockyards and abattoirs.

The connection to Bonheur, likely facilitated by Jules Breton, was significant for Virginie. Bonheur’s example demonstrated that a woman could achieve the highest levels of artistic recognition and professional success. This mentorship would have provided not only technical advice but also crucial encouragement and strategic guidance for navigating the male-dominated art world. Bonheur's own tenacity and dedication to her craft resonated with Virginie's ambitions, reinforcing the importance of rigorous work and unwavering commitment. The influence of Bonheur can be seen not just in Demont-Breton's professional resolve but also in the strength and dignity she imparted to her female subjects.

Emergence in the Art World: Salon Success and Early Recognition

Virginie Demont-Breton made her official debut in the Parisian art scene at a young age. She first exhibited at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1880, the primary venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage in France. Her talent was quickly acknowledged. In 1881, her painting Femme de pêcheur (Fisherman's Wife) received an honorable mention, a significant achievement for a young artist. This was followed by a third-class medal at the Salon of 1883 for another work, solidifying her reputation as a rising star.

Her success was not confined to France. In 1883, she won a gold medal at the Amsterdam International Colonial and Export Exhibition for her painting La Plage (The Beach). This international acclaim further boosted her career. The Salon system, though often criticized for its academic conservatism, was the gateway to success. Artists like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Jean-Léon Gérôme dominated the Salon with their polished academic works, but there was also growing space for Realist and Naturalist painters who depicted contemporary life. Demont-Breton skillfully navigated this environment, presenting works that were both technically accomplished and emotionally resonant. Her early successes at the Salon and international exhibitions marked her as a serious talent, capable of competing at the highest levels.

Throughout the 1880s, she continued to exhibit regularly and garner accolades. She received further honorable mentions at the Paris Salon, for instance, for Calm Sea in 1884 and Bread Making in 1886. Her participation in the Universal Expositions (World's Fairs) in Paris also brought her significant recognition, including gold medals in both 1889 and 1900. These awards were testaments to her consistent quality and the appeal of her subject matter.

Artistic Style: Naturalism, Motherhood, and Coastal Life

Virginie Demont-Breton's artistic style is firmly rooted in French Naturalism, a literary and artistic movement that emerged in the late 19th century as an extension of Realism. Influenced by writers like Émile Zola, Naturalism sought to depict life with scientific objectivity and often focused on the struggles and environments of the working class. While Realist painters like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet had earlier championed the depiction of peasant life, Naturalists often brought a more detailed, sometimes grittier, and psychologically nuanced approach to their subjects.

Demont-Breton’s Naturalism was characterized by a compassionate and often poetic portrayal of her subjects, primarily the fisherfolk of the northern French coast, particularly around Wissant where she later settled. She was deeply moved by the lives of these communities, their resilience in the face of hardship, and the strong familial bonds that sustained them. Her paintings often focus on women and children, capturing moments of daily life, anxiety, and quiet heroism.

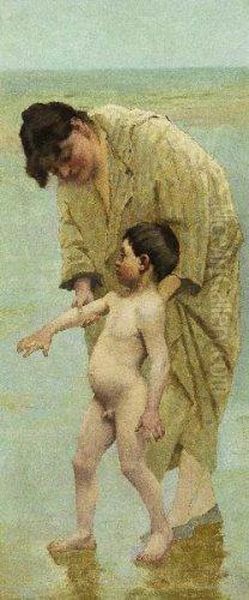

A recurring and central theme in her oeuvre is motherhood. She depicted mothers with their children with profound tenderness and empathy, highlighting the strength, protectiveness, and nurturing qualities of maternal love. Works like Mothers and Children on the Beach or scenes of women awaiting the return of their fishermen husbands convey a deep understanding of female experience. Her figures are not idealized beauties but real women, their faces and postures often reflecting the toil and anxieties of their lives, yet imbued with an undeniable dignity.

Her coastal scenes are rendered with meticulous attention to atmospheric effects – the quality of light on the water, the texture of sand and dunes, and the vastness of the sea and sky. These landscapes are not mere backdrops but integral parts of the narrative, often symbolizing the forces of nature that shape the lives of the coastal inhabitants. While her technique was grounded in academic tradition, with careful drawing and modeling, her later works sometimes showed a lighter palette and looser brushwork, hinting at an awareness of Impressionistic currents, though she remained fundamentally a Naturalist painter.

Notable Works: Capturing Humanity and Nature

Virginie Demont-Breton produced a substantial body of work, much of which resonated deeply with the public and critics alike. Several paintings stand out as representative of her style and thematic concerns.

_Femme de pêcheur_ (Fisherman's Wife, c. 1881): This early Salon success likely depicted a poignant scene of a fisherman's wife, perhaps anxiously awaiting her husband's return or engaged in daily toil. Such themes of domestic strength and vulnerability were central to her art. The painting's recognition at the Salon underscored her ability to convey powerful emotions through her realistic portrayal of everyday life. Decades later, a version of this subject or a similarly titled work achieved a significant auction price, attesting to its enduring appeal.

_L'Homme est en mer_ (The Man is at Sea, 1889): This is arguably one of her most famous works, not least because it was copied by Vincent van Gogh in 1889 during his time at the asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Van Gogh, who deeply admired the peasant painters like Millet and her father Jules Breton, saw a kindred spirit in Demont-Breton's depiction of the harsh realities and emotional toll of a fisherman's life. The painting typically shows a woman with her child in a humble cottage, her expression one of worry as her husband is out on the perilous sea. The dark interior contrasts with the stormy sea visible through a window or doorway, emphasizing the family's vulnerability. Van Gogh’s decision to copy this work highlights its emotional power and its alignment with his own sympathies for the working poor.

_Into the Water!_ (or _Au Bain_): This painting, often depicting a mother tenderly guiding her children into the sea, showcases Demont-Breton's skill in capturing intimate family moments and the innocence of childhood. The setting is typically a sunlit beach, and the mood is one of gentle care and joy. These works celebrate the simple pleasures of family life against the backdrop of the natural world. The figures are robust and healthy, reflecting a more optimistic aspect of coastal life compared to the anxieties portrayed in works like L'Homme est en mer.

_La Plage_ (The Beach, c. 1883): Awarded a gold medal in Amsterdam, this work likely captured a scene of activity or quiet contemplation on the beach, a setting Demont-Breton returned to throughout her career. It could have featured children playing, women mending nets, or simply figures gazing out at the sea, all rendered with her characteristic attention to detail and atmosphere.

_Stella Maris_ (Star of the Sea): This title, often associated with the Virgin Mary as a protector of seafarers, suggests a work with religious or symbolic overtones. Demont-Breton, while primarily a Naturalist, occasionally incorporated such elements, perhaps reflecting the deep faith of the fishing communities she portrayed. This work might have depicted a scene of prayer or a symbolic representation of hope and guidance amidst the dangers of the sea.

_Les Petits Bateaux_ (The Small Boats): This title indicates her interest in the maritime environment itself, not just the human figures within it. Such a work would have showcased her ability to render boats, water, and sky with accuracy and sensitivity, capturing the essence of the coastal landscape.

Her body of work consistently demonstrated a profound empathy for her subjects, a meticulous technique, and a talent for narrative composition that engaged viewers on an emotional level.

The Wissant Artists' Colony: A Creative Haven

In 1880, Virginie Breton married the painter Adrien Demont (1851-1928), who also specialized in landscapes and coastal scenes. The couple initially lived in Montgeron but, around 1881 or shortly thereafter, they discovered the picturesque fishing village of Wissant, located on the Opal Coast between Cap Gris-Nez and Cap Blanc-Nez. They were captivated by its unspoiled beauty, the dramatic coastline, and the traditional lives of its inhabitants.

In 1891, they built a remarkable villa in Wissant, named "Le Typhonium," designed by the Belgian architect Edmond De Vigne in an eclectic Neo-Egyptian style. This unique home became a focal point for an informal artists' colony that developed in Wissant. The Demont-Bretons attracted other artists to the area, drawn by the same inspiring landscapes and the supportive artistic community. Among the painters who frequented Wissant and were associated with their circle were Pierre Carrier-Belleuse (son of Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse), Georges Maroniez, Félix Planquette, and Henri Duhem. This "École de Wissant" or Wissant School, while not a formal movement with a manifesto, represented a group of artists sharing an interest in depicting the local scenery and way of life, often with a Naturalist or Realist sensibility. Virginie Demont-Breton was a central figure in this artistic milieu, her home a welcoming place for fellow painters.

A Tireless Advocate: Championing Women Artists

Beyond her personal artistic achievements, Virginie Demont-Breton was a passionate and effective advocate for the rights of women artists. She understood firsthand the systemic barriers that women faced in pursuing professional art careers, from limited access to formal training (especially life drawing from the nude model, considered essential for history painting and ambitious figure compositions) to exclusion from influential positions within art institutions.

She became a leading voice in the Union des Femmes Peintres et Sculpteurs (UFPS – Union of Women Painters and Sculptors), an organization founded in 1881 by the sculptor Hélène Bertaux (1825-1909). Demont-Breton served as the president of the UFPS from 1895 to 1901 (some sources state 1894-1901). During her tenure, she worked tirelessly to promote the work of women artists, organize exhibitions, and lobby for greater equality.

One of her most significant achievements was her role in the campaign to admit women to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the state-sponsored art school. For decades, women had been barred from enrolling, severely limiting their access to the highest level of academic training. Thanks to the persistent efforts of the UFPS, under leaders like Bertaux and Demont-Breton, the École des Beaux-Arts finally opened its doors to women in 1897, albeit initially in separate ateliers and with some restrictions. This was a landmark victory for women artists in France. Demont-Breton also advocated for women to be allowed to compete for the prestigious Prix de Rome, a scholarship that allowed artists to study in Italy, though this would take longer to achieve fully. Her efforts helped to dismantle some of the institutional sexism that had long hampered the progress of women in the arts, paving the way for future generations. She was a contemporary of other pioneering women artists like Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt, who, though more aligned with Impressionism, also navigated the challenges of being female artists in a male-dominated world.

Esteem and Honors: National and International Recognition

Virginie Demont-Breton's artistic talent and her advocacy work earned her considerable esteem and numerous honors throughout her career. Her consistent success at the Paris Salon and at international exhibitions, including the gold medals at the Amsterdam World's Fair (1883) and the Paris Universal Expositions (1889 and 1900), solidified her international reputation.

In 1894, she was made a Chevalier (Knight) of the Belgian Order of Leopold, a significant foreign honor. Perhaps the most prestigious recognition came in 1894 (some sources cite 1901 for Chevalier, with an upgrade to Officier later in 1914) when she was awarded the Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honor), France's highest order of merit. She was one of the very first women artists to receive this distinction; Rosa Bonheur had been the first in 1865. This award was a powerful acknowledgment of her artistic contributions and her standing in French culture. It also served as an inspiration for other women artists, demonstrating that their achievements could be recognized at the highest national level.

Her influence extended to official art bodies. In 1909, she was appointed as an elector for the Royal Academy of Arts in London, a testament to her respected position within the broader European art community. Her works were acquired by numerous museums in France and abroad, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, and museums in Lille, Arras, Douai, Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Ghent. American institutions like the Denver Art Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago also featured her work in exhibitions, indicating her transatlantic appeal.

Interactions with Contemporaries: Van Gogh and Beyond

Virginie Demont-Breton's life intersected with many prominent figures in the art world. Her family connections through her father, Jules Breton, naturally placed her within a network of established artists. Her marriage to Adrien Demont further expanded this circle. The Wissant colony brought her into regular contact with painters like Pierre Carrier-Belleuse and Georges Maroniez.

Her most famous, albeit indirect, connection with a contemporary was with Vincent van Gogh. As mentioned, Van Gogh created a painted copy of her work L'Homme est en mer in 1889. He saw the print of her painting in the journal Le Monde Illustré. In a letter to his brother Theo, Van Gogh expressed his admiration for the sentiment conveyed in the work, finding it "gripping." This act by Van Gogh, an artist who himself sought to capture the profound humanity of working people, is a significant endorsement of Demont-Breton's emotional depth and artistic skill. It places her work within the broader current of social realism and humanitarian concern that characterized much of late 19th-century art.

While she was not an Impressionist, she was certainly aware of the movement and its leading figures like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and her female counterparts Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt. Her commitment to Naturalism, however, aligned her more closely with painters like Léon Lhermitte or Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, who also focused on rural and working-class themes with a blend of realism and sentiment.

Later Career, Legacy, and Enduring Influence

Virginie Demont-Breton continued to paint and exhibit throughout her life, maintaining a consistent output and a dedication to her chosen themes. She also engaged in writing, publishing memoirs and reflections on art and life, including "Les maisons que j'ai connues" (The Houses I Have Known). Her villa, Le Typhonium, remained a testament to her artistic life and her connection to Wissant.

Her legacy is multifaceted. As an artist, she created a significant body of work that captured the life and spirit of coastal communities with empathy and skill. Her paintings of mothers and children are particularly enduring for their tender and honest portrayal of familial love. She successfully carved out a prominent career in a field dominated by men, achieving both critical acclaim and popular success.

Equally important is her legacy as an advocate for women artists. Her leadership in the UFPS and her role in opening the École des Beaux-Arts to women had a lasting impact on the opportunities available to subsequent generations of female artists in France. She was a pioneer who used her position and influence to challenge gender discrimination in the art world.

Today, Virginie Demont-Breton's work is being re-evaluated and appreciated by a new generation of art historians and museum-goers, particularly as there is a growing interest in rediscovering the contributions of women artists who were historically marginalized or overlooked. Her paintings are valued not only for their artistic merit but also for their social commentary and their heartfelt depiction of human experience. She remains an inspiring figure, a testament to artistic talent, resilience, and a commitment to social progress. Her life and work demonstrate the powerful intersection of art and advocacy, leaving an indelible mark on the history of French art.