Will Henry Stevens (1881-1949) stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of American Modernism, particularly renowned for his profound connection to the natural world and his innovative translation of its forms and spirit into a unique artistic language. Born in Vevay, Indiana, and deeply influenced by the environments he inhabited, from the banks of the Ohio River to the lush bayous of Louisiana and the misty peaks of the Appalachian Mountains, Stevens forged a career that saw him evolve from a naturalist painter into a sophisticated abstract artist. His journey reflects the broader currents of American art in the early 20th century, yet his voice remained distinctly personal, rooted in a spiritual reverence for nature and a relentless exploration of its expressive potential.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

William Henry Stevens was born on November 28, 1881, in Vevay, a small town nestled on the banks of the Ohio River in Indiana. This riverside upbringing was formative, instilling in him a deep and abiding love for the natural world that would become the central wellspring of his artistic inspiration throughout his life. The rhythms of the river, the changing seasons, the flora and fauna of the region – these were the early sights and sounds that shaped his aesthetic sensibilities. Even as a young man, Stevens demonstrated a keen observational skill and a desire to capture the essence of his surroundings. This early immersion in nature was not merely a passive experience; it was an active engagement that would later translate into a dynamic and deeply felt artistic practice. His formative years were spent absorbing the subtle nuances of the American landscape, an experience that laid a crucial foundation for his later, more abstract interpretations of nature's power and beauty.

His family later moved to Louisville, Kentucky, another city on the Ohio River, further cementing his connection to this vital waterway and its surrounding landscapes. It was in this environment that his artistic inclinations began to take more formal shape, leading him to seek out instruction that would hone his burgeoning talent.

Formal Training and Influences

Recognizing his artistic promise, Stevens enrolled at the Cincinnati Art Academy in 1901. The Academy, one of the oldest art schools in the United States west of the Appalachian Mountains, provided him with a solid grounding in academic traditions. Here, he would have been exposed to rigorous training in drawing and painting, likely studying under artists who themselves were navigating the transition from 19th-century academicism to newer, more expressive modes of art-making. Instructors such as Frank Duveneck, a prominent figure at the Academy, were known for their painterly realism and Munich School influences, which emphasized bravura brushwork and a direct approach to the subject.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Stevens moved to New York City in 1906 to study at the prestigious Art Students League. This was a pivotal moment in his development. At the League, he came under the tutelage of William Merritt Chase, one of the most influential American art teachers of his generation. Chase, known for his dazzling Impressionist paintings and his charismatic teaching style, encouraged his students to develop their own individual voices while mastering technique. He championed plein air painting and a direct, spontaneous approach to capturing light and atmosphere. Stevens absorbed these lessons, and Chase's emphasis on individuality likely resonated with his own independent spirit.

During his time in New York, Stevens would also have been exposed to the burgeoning modern art scene. Exhibitions of European modernists, such as those at Alfred Stieglitz's 291 gallery, were beginning to introduce American artists and audiences to radical new ideas from artists like Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Paul Cézanne. While Stevens's early work remained largely representational, the seeds of modernism – its emphasis on subjective experience, formal innovation, and the expressive power of color and line – were undoubtedly planted during this period. He also exhibited with the Society of Western Artists between 1907 and 1918, indicating his continued connection to regional art movements even as he absorbed metropolitan influences.

The Journey South and a Career at Newcomb College

After his studies, Stevens's path eventually led him south. He taught for a period at the University of Kentucky in Lexington. However, a more defining chapter of his career began in 1921 when he accepted a position at the H. Sophie Newcomb Memorial College, the women's college of Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana. He would remain a dedicated and influential professor of art at Newcomb for 27 years, retiring in 1948.

New Orleans, with its unique cultural tapestry, subtropical climate, and distinctive landscapes of bayous, swamps, and lush vegetation, provided Stevens with a rich new environment for artistic exploration. The humid air, the vibrant colors, and the exotic flora of the region deeply permeated his work. At Newcomb, he became a respected figure, guiding generations of young women artists. His colleagues at Newcomb included other notable artists such as Ellsworth Woodward and William Woodward, brothers who were instrumental in developing the art program and the renowned Newcomb Pottery. Stevens's presence contributed to the college's reputation as a significant center for art education in the South.

His teaching philosophy, likely influenced by Chase, would have encouraged students to observe nature closely while also exploring personal expression. He himself continued to paint prolifically, dividing his time between his teaching duties and his own artistic pursuits, often venturing into the Louisiana countryside and, during summers, to the mountains of North Carolina and Tennessee to sketch and paint.

Artistic Evolution: From Naturalism to Modernism

Stevens's artistic output can be broadly seen as an evolution through several stylistic phases, though his core inspiration—nature—remained constant. His journey was one of increasing abstraction, moving from more literal depictions to highly symbolic and non-objective interpretations.

Early Naturalistic and Impressionistic Works

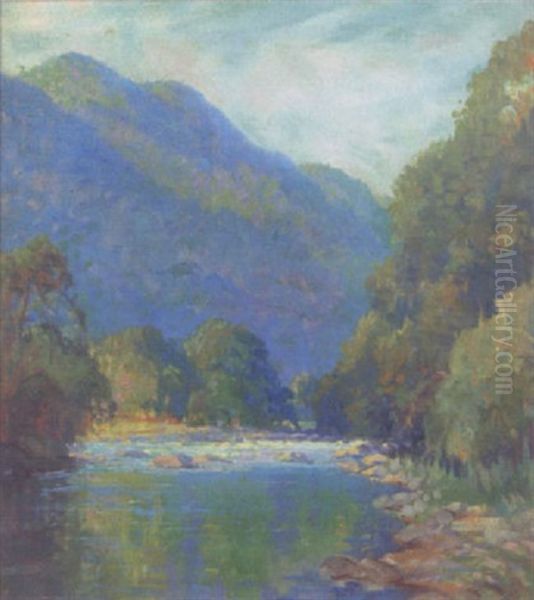

In his early career, Stevens worked in a naturalistic and Impressionistic vein. His landscapes from this period, influenced by his academic training and the teachings of Chase, focused on capturing the effects of light and atmosphere. These works often depicted the familiar scenes of the Ohio River Valley or the Kentucky countryside. They were characterized by a sensitive observation of nature, a harmonious palette, and a concern for traditional composition. While representational, these early pieces already hinted at a poetic sensibility and a desire to convey the mood and spirit of a place, not just its superficial appearance. He demonstrated a mastery of traditional techniques, creating works that were well-received and found a ready audience.

Embracing Modernism: The Influence of Nature's Rhythms

As Stevens matured, his work began to show the clear influence of modern artistic principles. He became increasingly interested in the underlying structures and rhythms of nature, rather than just its surface appearance. His exposure to European and American modernists, such as Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and Georgia O'Keeffe, who were all finding new ways to interpret the American landscape, likely played a role in this shift. These artists, each in their own way, sought to express the spiritual or emotional essence of nature through simplified forms, expressive color, and dynamic compositions.

Stevens began to experiment with flattening pictorial space, emphasizing pattern and design, and using color more subjectively. His landscapes became less about topographical accuracy and more about conveying an emotional or spiritual response to the natural world. He was particularly drawn to the theories of Wassily Kandinsky, who wrote about the spiritual in art and the expressive potential of abstract forms and colors. Stevens, like Kandinsky, believed that art could communicate on a deeper, more intuitive level, bypassing literal representation to touch the viewer's soul. He also shared an affinity with the work of Paul Klee, whose delicate lines and imaginative transformations of natural motifs into near-abstract symbols resonated with Stevens's own evolving approach.

The Abstract Language of Nature

In the later stages of his career, particularly from the 1930s onwards, Stevens moved decisively towards abstraction. However, his abstraction was almost always rooted in his observations of nature. He developed a personal vocabulary of forms, lines, and colors derived from natural elements: the curve of a hill, the jagged silhouette of a mountain range, the sinuous flow of a river, the delicate structure of a leaf, or the ephemeral patterns of clouds and mist.

His abstract works are not cold or purely formal exercises; they are imbued with the vitality and mystery of the natural world. He often spoke of "listening" to nature and allowing its forms to suggest themselves to him. His process involved intense observation, followed by a period of imaginative transformation in the studio. He sought to capture the "spirit" or "rhythm" of a place, using what he described as "an arrangement of design, color, and form that will have the same effect on the beholder that the natural scene had on the artist."

His works from this period often feature flowing, organic lines, layered colors, and a sense of dynamic movement. Some pieces verge on complete non-objectivity, yet they retain an organic quality that speaks of their natural origins. He was a master of creating mood and atmosphere, whether it was the misty tranquility of the Great Smoky Mountains or the vibrant energy of a Louisiana swamp. An untitled mountain scene from 1946, for example, exemplifies this mature abstract style, where landscape elements are distilled into powerful, evocative forms and colors that convey the sublime grandeur of the mountains.

Themes, Techniques, and Representative Works

Nature, in its myriad forms, was the overarching theme of Will Henry Stevens's art. He was particularly drawn to the landscapes of the American South: the bayous, swamps, and coastal areas of Louisiana, and the mountains of North Carolina and Tennessee, especially the Great Smoky Mountains. He rendered these scenes with a deep empathy, capturing their unique character and atmosphere.

Stevens was a versatile artist, proficient in several media. He worked extensively in oils, but he was also a master of watercolor and pastel. His watercolors are characterized by their fluidity and transparency, often capturing the ephemeral effects of light and weather. His pastels, a medium he used with particular brilliance, allowed him to achieve rich, velvety textures and vibrant colors. He often combined media, or used pastel in a way that was both graphic and painterly. His technique was often direct and spontaneous, reflecting his desire to capture the immediate sensation of being in nature.

While specific titles of many works are not always widely known, his oeuvre can be categorized by its subject matter and style:

Early Ohio River and Kentucky Landscapes: More traditional, Impressionistic scenes.

Louisiana Bayou and Swamp Scenes: These works capture the lush, humid atmosphere of the Louisiana lowlands, often with a focus on water, vegetation, and dramatic skies. They range from representational to semi-abstract.

Appalachian Mountain Landscapes: Stevens spent many summers in the mountains of North Carolina and Tennessee. His depictions of the Great Smoky Mountains are among his most powerful works, conveying their grandeur, mystery, and ever-changing moods. These often show a progression towards greater abstraction.

Abstract Compositions: These works, often inspired by natural forms but not directly representational, showcase his mastery of color, line, and design. They are lyrical and evocative, inviting contemplation. He referred to some of these as "visual poems" or "nature symphonies."

His works often carry titles that are descriptive yet poetic, such as "Mountain Rhythm," "Bayou Fantasy," or simply "Abstraction." The Asheville Art Museum, which holds a significant collection of his work (over 40 pieces), provides a good overview of his range, from representational depictions of the Smoky Mountains and New Orleans environs to purely abstract compositions.

Connections and Contemporaries

Will Henry Stevens operated within a rich artistic milieu, both as a student and as a mature artist and educator. His primary mentor, William Merritt Chase, connected him to a lineage of American Impressionism and a tradition of strong technical grounding.

In New Orleans, his colleagues at Newcomb College, particularly Ellsworth Woodward and William Woodward, were key figures in the Southern art scene. While their styles differed from Stevens's later modernism, they fostered an environment of artistic activity and education.

Stevens's work shows affinities with several leading American modernists who also drew inspiration from nature:

Arthur Dove: Considered one of America's first abstract painters, Dove created powerful, nature-based abstractions that sought to capture the "spirit of the place." Stevens shared Dove's commitment to finding an abstract language for natural experience.

Georgia O'Keeffe: Famous for her magnified flowers and stark New Mexico landscapes, O'Keeffe, like Stevens, found profound inspiration in natural forms, simplifying and abstracting them to reveal their essential beauty and power.

John Marin: Known for his dynamic watercolors of the Maine coast and New York City, Marin's expressive, semi-abstract style captured the energy and vitality of his subjects. Stevens's more abstract landscapes share this sense of dynamism.

Marsden Hartley: Another important American modernist who painted powerful, expressive landscapes, particularly of Maine. Hartley, like Stevens, imbued his landscapes with deep personal feeling.

Charles Burchfield: While often more overtly mystical and symbolic, Burchfield's intense, personal interpretations of nature, often focusing on weather and seasonal change, share a spiritual kinship with Stevens's approach.

While it's not always possible to document direct contact, Stevens would have been aware of the broader developments in European modernism. The influence of artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee on his abstract work seems undeniable, particularly their theories on the spiritual and expressive capacities of color and non-representational form. He may also have absorbed lessons from Post-Impressionists like Paul Cézanne in terms of structuring nature through form and color, or from Henri Matisse regarding the liberation of color for expressive purposes. His work, while uniquely his own, participated in the international dialogue of modern art that sought new ways of seeing and representing the world.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Throughout his career, Will Henry Stevens exhibited his work in various regional and national venues. He showed in New York and Chicago, indicating that his art was recognized beyond the South. His long association with the Society of Western Artists (1907-1918) provided regular exhibition opportunities early in his career. Later, his work was featured in exhibitions in New Orleans and other Southern cities.

Despite his significant contributions, Stevens did not achieve the same level of widespread fame during his lifetime as some of his Northern modernist contemporaries. This may have been due in part to his quiet, unassuming nature and his decision to base his career primarily in the South, away from the major art centers of New York.

However, in recent decades, there has been a growing appreciation for his work. His paintings are now included in the permanent collections of several important museums, including:

The Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C.

The Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans, Louisiana

The Asheville Art Museum, Asheville, North Carolina

The Morris Museum of Art, Augusta, Georgia

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), California

The Brooklyn Museum, New York

Retrospectives and scholarly attention have helped to re-evaluate his position in American art history, recognizing him as a pioneer of Southern Modernism and a distinctive voice in 20th-century American painting.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Will Henry Stevens continued to teach at Newcomb College until his retirement in 1948. Despite battling leukemia in his later years, he remained dedicated to his art. His wife, Grace, was a constant support throughout his life and career. He passed away on August 25, 1949, in Madison, Indiana, not far from his Vevay birthplace, bringing his life's journey full circle.

His legacy is multifaceted. As an educator, he influenced generations of students at Newcomb College, contributing to the artistic development of the South. As an artist, he created a significant body of work that masterfully bridged the gap between representational landscape painting and modernist abstraction. He demonstrated that modernism was not solely an urban phenomenon but could also find fertile ground in the regional landscapes and experiences of America.

Stevens's most enduring contribution lies in his profound and lyrical interpretations of nature. He was not content to merely replicate the outward appearance of the world; he sought to penetrate its deeper realities, to capture its spirit, its rhythms, and its emotional resonance. His art invites viewers to look beyond the surface and to experience the natural world with a heightened sense of wonder and introspection. He remains a testament to the power of an artist who, by staying true to his personal vision and his deep connection to place, created a body of work that continues to speak to us today.

Conclusion

Will Henry Stevens was a quiet innovator, an artist who forged a unique path through the complex currents of early 20th-century American art. His deep spiritual connection to the natural world, cultivated from his boyhood on the Ohio River and enriched by his experiences in the diverse landscapes of the American South, fueled a lifelong artistic exploration. From his early naturalistic renderings to his mature, lyrical abstractions, Stevens sought to convey the essence and emotional impact of nature. Influenced by teachers like William Merritt Chase and inspired by the broader movements of modernism, he developed a personal visual language that was both sophisticated and deeply felt. As an influential educator at Newcomb College and a prolific painter, he left an indelible mark on Southern art. Today, his work is increasingly recognized for its beauty, its originality, and its significant contribution to the story of American Modernism, securing his place as a distinguished interpreter of the American landscape and a poet of abstract form.