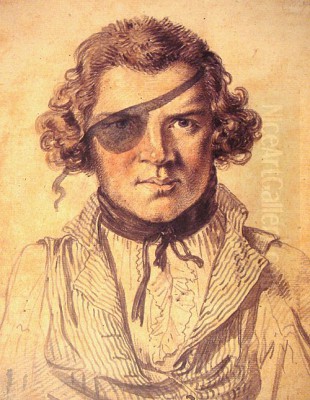

William Alexander (1767-1816) stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the annals of British art. His unique experiences as an official draughtsman on the first British embassy to China provided him with unparalleled access to a land largely mysterious to the Western world. The body of work he produced, primarily in watercolour, not only offered Europeans a seemingly authentic glimpse into the landscapes, customs, and attire of late 18th-century China but also cemented his reputation as a meticulous observer and a skilled artist. His contributions extend beyond his Chinese subjects, encompassing a career as an educator and as the first Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the nascent British Museum, making him a pivotal figure in the institutionalization of art in Britain.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born on April 10, 1767, in Maidstone, Kent, William Alexander was the son of James Alexander, a coachmaker. This practical, craft-based family background might have instilled in him an appreciation for precision and detail from an early age. His innate talent for drawing became evident early on, prompting his family to support his artistic inclinations. By 1782, at the age of fifteen, he moved to London, the burgeoning center of the British art world, to formally pursue his studies.

In London, Alexander is believed to have initially studied under William Pars (1742-1782), a notable watercolourist and draughtsman known for his topographical views, particularly those made on expeditions to Greece and Asia Minor. Pars himself had been a student of the Shipley's drawing school, a significant institution for aspiring artists. Though Pars died shortly after Alexander would have begun any tutelage, his influence, emphasizing accuracy and careful delineation, would have been a formative one. Subsequently, in 1784, Alexander enrolled in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. Here, he would have been exposed to the prevailing artistic theories and practices of the day, under the overarching influence of its first President, Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), and other prominent Academicians like Benjamin West (1738-1820) and Henry Fuseli (1741-1825), who became Professor of Painting in 1799. The Royal Academy curriculum stressed drawing from casts of classical sculpture and from life, providing a rigorous foundation for young artists.

The Call of the East: The Macartney Embassy

The most defining chapter of William Alexander's career began in 1792 when he was appointed, at the relatively young age of 25, as Junior Draughtsman to the Macartney Embassy. This ambitious diplomatic mission, led by Lord George Macartney, was the first official British embassy to the court of the Qianlong Emperor of China. Its primary objectives were to establish formal diplomatic relations, negotiate better trade terms, and secure a British trading base on Chinese soil. The embassy was equipped with scientists, scholars, and artists to document the journey and the distant empire, reflecting the Enlightenment's thirst for knowledge and empirical observation.

Alexander's role, alongside the senior artist Thomas Hickey (1741-1824), who was primarily a portrait painter, was to create a visual record of the embassy's progress, the landscapes encountered, the architecture, and the people of China. While Hickey focused more on formal portraiture, Alexander's remit was broader, encompassing the topographical and ethnographic aspects of the mission. The journey itself was an arduous one, sailing via Madeira, Tenerife, Rio de Janeiro, and the Cape of Good Hope, before reaching the coast of China. This voyage provided Alexander with diverse subjects even before reaching the primary destination.

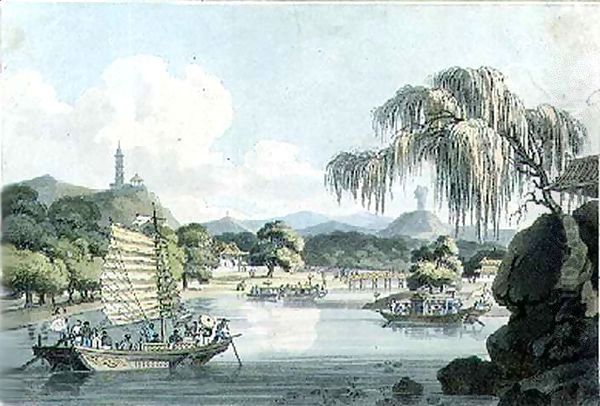

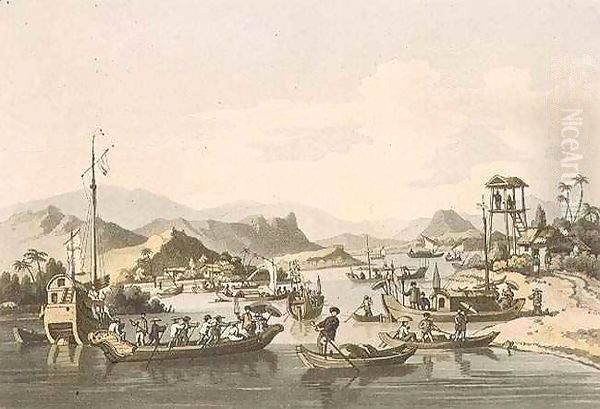

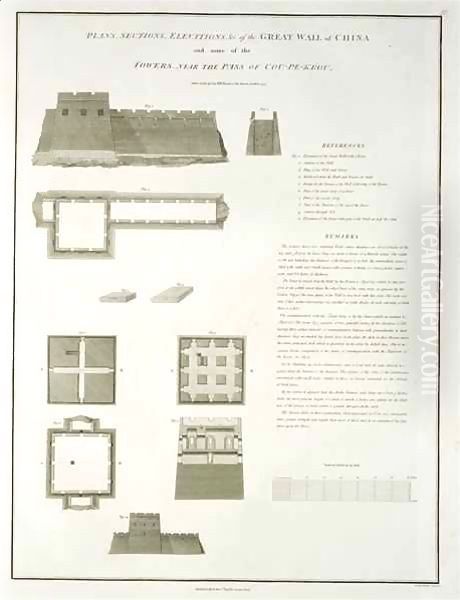

The embassy travelled extensively within China, from the coast up the Hai River (Peiho) towards Peking (Beijing), and then to the imperial summer retreat at Jehol (Rehe). They were also granted passage along the Grand Canal. This unprecedented access allowed Alexander to sketch prolifically, capturing scenes that no European artist had previously witnessed in such detail or scope. He documented urban environments, rural landscapes, imperial palaces, modes of transport like junks and barges, and the diverse attire and activities of the Chinese populace, from high officials to common laborers.

An Artist's Eye in China: Observation and Representation

Alexander's approach to his task was characterized by a commitment to accuracy and a keen eye for detail. Working primarily in pencil and watercolour, he produced a vast number of sketches and finished drawings. His style was well-suited to the demands of topographical and ethnographic recording. It was less about grand artistic statements in the manner of historical painting, as championed by Reynolds, and more aligned with the burgeoning tradition of British watercolour landscape, exemplified by artists like Paul Sandby (1731-1809), often called the "father of English watercolour," who had already established a market for precise and pleasing views.

Unlike some European artists who exoticized or romanticized foreign lands, Alexander strove for a degree of verisimilitude, though inevitably filtered through a Western artistic sensibility. His depictions of Chinese architecture, for instance, carefully noted structural details and ornamentation. His figures, while sometimes generalized, conveyed a sense of the everyday life and social hierarchy he observed. He was particularly attentive to costume, which was of great interest to European audiences eager to understand the customs of this distant empire.

The conditions under which he worked were often challenging. The embassy faced suspicion and restrictions from Chinese officials, and the pace of travel required quick sketching. Nevertheless, Alexander amassed an invaluable portfolio. His work provided a counterpoint to the often fanciful and stereotyped images of China prevalent in the popular Chinoiserie style, offering instead a more grounded, observational perspective. His visual record was crucial, as photography was still decades away, making skilled draughtsmen the primary means of visually documenting such expeditions. His work can be compared to that of other artists on voyages of discovery, such as John Webber (1751-1793), who accompanied Captain James Cook on his third Pacific voyage and whose images of Polynesian and Native American cultures greatly informed European understanding.

Artistic Style and Technique

William Alexander's artistic style is firmly rooted in the British topographical watercolour tradition of the late 18th century. His works are characterized by clear, delicate washes of colour, precise draughtsmanship, and a balanced, often serene, composition. He typically began with a detailed pencil underdrawing, over which he applied transparent layers of watercolour. His palette was generally subdued but harmonious, capturing the atmospheric qualities of the Chinese landscape and the nuances of costume and architecture.

His figures are often an integral part of his landscapes and cityscapes, providing scale and animating the scenes, rather than being the primary focus in the way a portraitist like Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830) or Henry Raeburn (1756-1823) would approach a subject. There is a certain calmness and order in his compositions, reflecting the prevailing aesthetic preferences for clarity and picturesque beauty. While his contemporaries like Thomas Girtin (1775-1802) and the young J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) were beginning to push the boundaries of watercolour towards more expressive and romantic interpretations of landscape, Alexander's work remained more closely aligned with the documentary and illustrative function inherent in his role on the embassy.

The meticulous nature of his work was essential for its later use in engravings. The clarity of his lines and the distinctness of his forms translated well into the print medium, which was the primary means by which his images reached a wider public. His attention to detail, from the rigging of a junk to the pattern on a mandarin's robe, provided a wealth of information for viewers back in Britain. This precision also distinguished his work from the more generalized or imaginative depictions of China that had characterized earlier Chinoiserie.

Major Works and Publications

Upon his return to England in 1794, William Alexander set about transforming his numerous sketches and field studies into finished watercolours. These formed the basis for several important publications that disseminated his vision of China to a curious British and European audience. One of his most significant contributions was the series of engravings made from his drawings for Sir George Staunton's official account of the embassy, "An Authentic Account of an Embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China," published in 1797. Staunton was the embassy's secretary, and Alexander's illustrations were crucial to the success and impact of this widely read two-volume work.

Alexander also published his own works, most notably "The Costume of China," which appeared in 1805. This volume featured 48 hand-coloured aquatints based on his drawings, each accompanied by an explanatory text. It provided a detailed survey of Chinese dress across different social strata and occupations, from imperial officials and scholars to soldiers, boatmen, and street vendors. The book was immensely popular and influential, further shaping European perceptions of Chinese society and contributing significantly to the ongoing fascination with Chinoiserie, albeit with a greater degree of perceived authenticity.

Another important publication was "Picturesque Representations of the Dress and Manners of the Chinese" (1814). His drawings also illustrated John Barrow's "Travels in China" (1804) and "A Voyage to Cochinchina" (1806). The process of creating these published images often involved collaboration with skilled engravers, such as Joseph Constantine Stadler, who translated Alexander's delicate watercolours into printable plates. The hand-colouring of these aquatints was a laborious process, often done by teams of colourists, but it allowed for a closer approximation of the artist's original intentions. These publications ensured that Alexander's vision of China reached a broad audience and had a lasting impact on Western visual culture. His works were also used as source material by other artists and designers, including the notable topographical artist Thomas Allom (1804-1872), who, though he never visited China himself, produced popular illustrated books on the country, drawing inspiration from earlier artists like Alexander.

Return to England and Later Career

After the Macartney Embassy, William Alexander did not return to distant lands but established a successful career in England. Besides working on his Chinese subjects for publication, he also produced watercolours of British scenery and antiquities. His reputation as a skilled draughtsman and a reliable observer was well established.

In 1802, he was appointed Professor of Drawing at the Royal Military College at Great Marlow (which later moved to Sandhurst). This position provided him with a steady income and recognized his pedagogical abilities. Teaching military cadets the rudiments of topographical drawing was an important skill for reconnaissance and map-making, and Alexander's precision and clarity were well-suited to this task.

A more prestigious appointment came in 1808 when he became the first Assistant Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum. The museum, founded in 1753, was still developing its collections and organizational structure. The Department of Prints and Drawings was formally established with Alexander at its helm (though the title was "Assistant Keeper," he effectively ran the department under the Principal Librarian). He was responsible for cataloguing, conserving, and making accessible the growing collection of works on paper. His tenure saw the acquisition of significant collections, and he played a crucial role in laying the foundations for what would become one of_the world's foremost collections of prints and drawings. His own artistic practice, with its emphasis on careful observation and meticulous technique, informed his curatorial approach. He remained in this post until his untimely death.

Influence and Legacy

William Alexander's influence was multifaceted. His images of China provided a primary visual source for Western understanding of the Qing Empire for several decades. They informed not only popular perceptions but also academic study and artistic representations by others. While the Macartney Embassy itself failed in most of its diplomatic objectives – Emperor Qianlong famously dismissed British overtures for expanded trade – the cultural and informational yield, significantly shaped by Alexander's artistry, was substantial.

His work contributed to the visual vocabulary of Chinoiserie, lending it a new layer of ethnographic detail. While artists like Jean-Baptiste Pillement (1728-1808) had earlier popularized a more fanciful and decorative style of Chinoiserie, Alexander's work offered images that were perceived as more authentic and documentary. This appealed to a public increasingly interested in factual accounts of foreign cultures, a trend also seen in the popularity of travel narratives and scientific expeditions.

As an educator at the Royal Military College, he imparted practical drawing skills to a generation of officers. At the British Museum, his foundational work in organizing and developing the collection of prints and drawings was of lasting importance. He helped to establish standards for curatorship and collection management that would be built upon by his successors.

His artistic legacy is primarily that of a highly skilled watercolourist and an invaluable visual chronicler. While he may not have achieved the revolutionary artistic innovations of some of his contemporaries like Turner or Girtin, or the society portraiture fame of Sir Thomas Lawrence, his contribution lies in the unique historical and cultural significance of his work. His depictions of China remain a vital resource for historians studying Sino-British relations and 18th-century Chinese society. Artists like George Chinnery (1774-1852), who later spent many years painting in India and China, would build upon the Western tradition of depicting Asia, but Alexander was a crucial early pioneer in providing extensive, first-hand visual documentation of the Chinese interior. Even earlier, the Italian Jesuit painter Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining, 1688-1766) had served the Chinese court, blending Western techniques with Chinese themes, but his work was primarily for the imperial court, whereas Alexander's was for a Western audience.

Alexander and His Contemporaries

William Alexander operated within a vibrant British art scene. At the Royal Academy, he would have been aware of the grand manner of history painting promoted by Reynolds and West, but his own path diverged towards the more intimate and descriptive medium of watercolour. The late 18th and early 19th centuries saw a "golden age" of English watercolour, with artists like Thomas Girtin, J.M.W. Turner, John Sell Cotman (1782-1842), and David Cox (1783-1859) elevating the medium to new heights of expressiveness and technical sophistication. While Alexander's style was more conservative and documentary, he was part of this broader flourishing.

His work on the Macartney Embassy can be seen in the context of other artist-travelers. The voyages of Captain Cook, documented by artists like Sydney Parkinson (c. 1745-1771) and John Webber, had already whetted the public's appetite for images of exotic lands. In India, Thomas Daniell (1749-1840) and his nephew William Daniell (1769-1837) were producing their monumental "Oriental Scenery," a series of aquatints that offered breathtaking views of Indian architecture and landscapes. Alexander's Chinese works complemented these endeavors, expanding the British visual understanding of the East.

His role at the British Museum also connected him to the scholarly and collecting worlds. He would have interacted with antiquarians, collectors, and fellow scholars, contributing to the intellectual life of the capital. His meticulous cataloguing of prints and drawings, including works by Old Masters and contemporary artists, demonstrated a broad appreciation for the graphic arts.

The Enduring Record

William Alexander died relatively young, at the age of 49, on July 23, 1816, in Maidstone, reportedly from a "brain fever" (possibly meningitis or a stroke). He was buried in the churchyard of nearby Boxley. Despite his premature death, he left behind a significant body of work and a lasting legacy.

His drawings and watercolours are held in major collections worldwide, including the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Yale Center for British Art, and the National Gallery of Ireland. They continue to be studied for their artistic merit, their historical content, and their role in shaping cross-cultural perceptions. His images offer a window into a specific moment in time, capturing the encounter between two vastly different civilizations.

The "truthfulness" of Alexander's depictions has been debated by scholars. While he aimed for accuracy, his vision was inevitably shaped by his own cultural background and the expectations of his audience. Nevertheless, his work remains an invaluable primary source, offering insights that textual accounts alone cannot provide. He captured the visual texture of Qing Dynasty China – its bustling waterways, its distinctive architecture, the faces and attire of its people – with a skill and dedication that commands respect.

Conclusion

William Alexander was more than just a competent topographical artist. He was an explorer through his art, venturing into a world largely unknown to his compatriots and bringing back a visual treasure trove. His meticulous watercolours and the widely circulated engravings based upon them played a crucial role in forming Britain's visual understanding of China at a pivotal moment in global history. His subsequent career as an influential educator and as the foundational Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum further underscores his importance to British art and culture. Though perhaps not as famous as some of his more flamboyant contemporaries, William Alexander's diligent artistry and his unique experiences ensure his enduring significance as a chronicler of worlds, both at home and afar. His work serves as a testament to the power of art to document, interpret, and bridge cultural divides.