John William Godward stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of late Victorian and early Edwardian art. A painter deeply committed to the ideals of Neoclassicism, he carved a distinct niche for himself with meticulously rendered depictions of female beauty set against the backdrop of ancient Greece and Rome. Born into an era where the Academic tradition still held sway but was increasingly challenged by burgeoning modernist movements, Godward's life and career encapsulate the poignant transition of artistic tastes at the turn of the 20th century. His technical brilliance was undeniable, yet his adherence to a specific, idealized aesthetic ultimately led to professional isolation and personal tragedy. This exploration delves into the life, work, influences, and legacy of an artist whose serene canvases belie a turbulent inner world.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

John William Godward was born in Wimbledon, Surrey, on August 9, 1861. His family background was one of relative affluence; his father, John Godward, was a successful investment clerk working with the Law Life Assurance Society, and his paternal grandfather had been associated with the prestigious Lloyd's of London. Despite this comfortable upbringing, Godward's path towards an artistic career was fraught with familial opposition. His parents held conventional expectations for their son, envisioning a stable career in business, perhaps following his father into the world of insurance or finance.

The young Godward, however, harboured different aspirations. Initially, he pursued training as an architect, studying under William Hoff Wontner from 1879 to 1881. This architectural grounding likely contributed to his later mastery in depicting classical structures and his keen sense of spatial composition. Yet, the lure of painting proved stronger. His family's disapproval of this chosen path is reported to have been strenuous, contributing to Godward developing a shy, reclusive personality that would mark his adult life. This lack of familial support created an emotional distance that persisted throughout his career.

Despite the opposition, Godward persevered. He sought formal art training, attending the St John's Wood Art School and later the Clapham School of Art. It was during this formative period, likely in the early 1880s, that he befriended fellow aspiring artist William Clarke. Clarke, who would become a portrait painter, shared educational backgrounds with Godward, and their friendship provided a measure of camaraderie in the competitive London art world. This early connection highlights Godward's integration, albeit perhaps tentatively, into the circles of aspiring artists of his generation.

The Shaping Influences: Leighton and Alma-Tadema

Godward's artistic development did not occur in a vacuum. He emerged during the high point of Victorian Academic painting, a style characterized by technical polish, historical or mythological subject matter, and adherence to classical principles of composition and form. Two towering figures of this establishment profoundly shaped Godward's aesthetic: Frederic Leighton and Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema.

Frederic Leighton, later Lord Leighton, was President of the Royal Academy and a leading proponent of Neoclassicism. His works, often featuring statuesque figures in flowing drapery set within idealized classical environments, exemplified the pursuit of beauty and formal harmony. Godward clearly admired Leighton's approach, adopting a similar commitment to classical themes and elegant figuration. While perhaps not a direct pupil in the studio sense, Godward absorbed Leighton's influence through exhibitions and the prevailing artistic discourse, striving for a comparable level of refinement and idealization in his own depictions of classical womanhood. Some critics see echoes of Leighton's famous Flaming June in the languid poses and rich colours found in some of Godward's compositions.

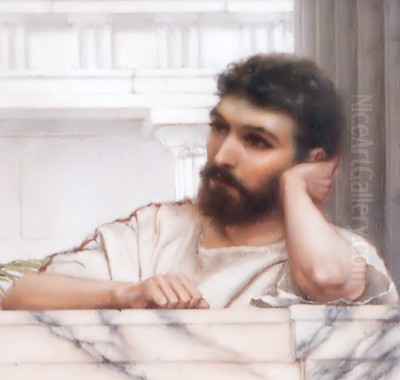

Even more direct and pervasive was the influence of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema. A Dutch-born painter who settled in London and achieved immense fame, Alma-Tadema specialized in scenes of everyday life in ancient Rome and Greece, rendered with astonishing archaeological detail and sensuous textures. Godward is often described as Alma-Tadema's protégé or follower. He adopted his mentor's fascination with classical domesticity, his meticulous attention to detail – particularly the rendering of marble, fabrics, and flowers – and his ability to evoke a sun-drenched Mediterranean atmosphere. The comparison is undeniable; works like Godward's In The Tepidarium (1913) clearly reference Alma-Tadema's earlier painting of the same name (1881), showcasing a shared interest in intimate classical settings.

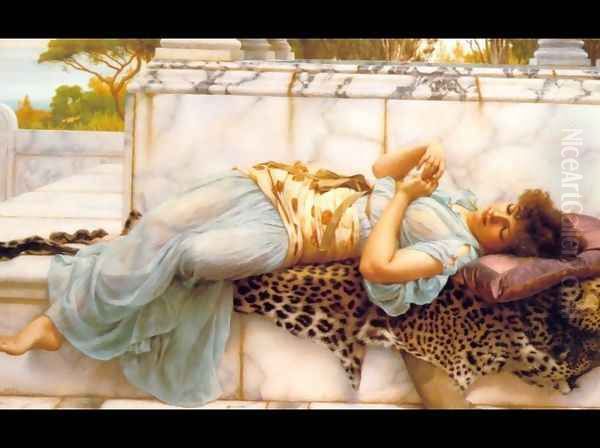

However, while deeply indebted to Alma-Tadema, Godward developed his own distinct variations on the theme. His focus remained almost exclusively on solitary female figures or small groups, often depicted in moments of quiet contemplation or leisure. There is perhaps less narrative complexity than in Alma-Tadema's work, with a greater emphasis on pure aesthetic beauty and mood. Godward became a master of texture, his rendering of cool, veined marble surfaces contrasting with soft skin, lustrous silks, and animal furs becoming a hallmark of his style, earning his circle the informal label of the "Marble School." Other artists associated with this highly finished, classicizing style included Albert Moore and Edward Poynter, fellow members of the Royal Academy who prioritized aesthetic harmony and classical motifs.

Mature Style: The Godward Woman and Her World

By the late 1880s and 1890s, John William Godward had established his signature style. His debut at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition came in 1887, and he continued to exhibit there regularly for nearly two decades. His paintings found favour with collectors and dealers, notably Thomas McLean, who also supported his friend William Clarke. Godward's canvases became synonymous with a particular vision of antiquity: serene, sunlit, and populated by beautiful young women.

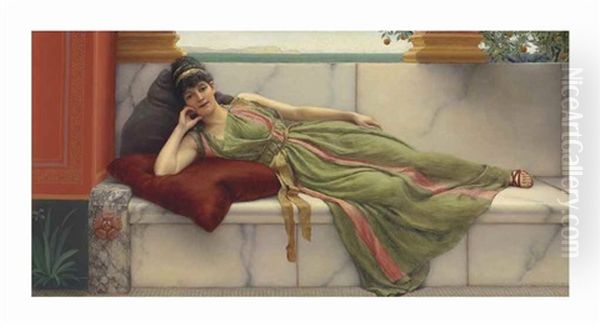

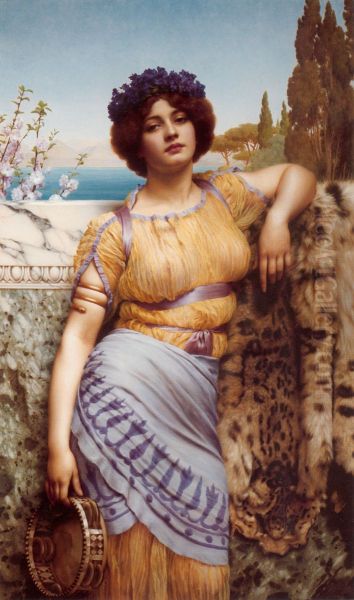

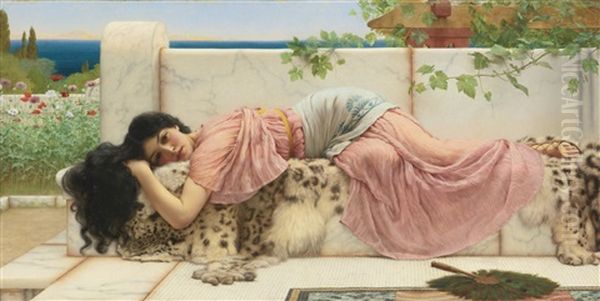

The quintessential Godward subject is a woman, often dark-haired with classical features, clad in finely draped Grecian or Roman attire. She is typically shown reclining on a marble bench, gazing pensively into the distance, arranging flowers, reading a scroll, or simply enjoying a moment of dolce far niente – sweet idleness. The settings are meticulously crafted architectural niches, terraces overlooking azure seas, or enclosed gardens filled with vibrant poppies, anemones, or oleanders. Marble is ubiquitous, rendered with almost photographic precision, its cool solidity providing a perfect foil for the warmth of human skin and the softness of fabric.

Titles often reinforce the mood of tranquil beauty and classical allusion: A Siesta, The Quiet Pet, With Violets Wreathed and Robe of Saffron Hue, An Italian Girl's Head, Ionian Dancing Girl, The Betrothed, When the Heart is Young. These works are not generally concerned with dramatic historical events or complex mythological narratives, unlike some other Neoclassical painters such as Jean-Léon Gérôme in France. Instead, Godward focused on evoking an atmosphere of timeless beauty, peace, and sensual pleasure. His classicism was less heroic and more decorative, aligning with aspects of the Aesthetic Movement which prioritized "art for art's sake."

His technical execution was consistently brilliant. Godward employed fine brushes and smooth paint application to achieve a highly polished finish with little visible brushwork. His understanding of light, particularly the bright Mediterranean sun casting sharp shadows and illuminating textures, was exceptional. The rendering of fabrics – the diaphanous folds of silk, the heavier drape of wool, the occasional inclusion of animal pelts – demonstrates extraordinary skill. This technical virtuosity, combined with the appealing subject matter, ensured his popularity during the late Victorian and Edwardian periods, offering audiences an escape into an idealized, untroubled past.

Life in London and the Italian Sojourn

Despite his professional success, Godward's personal life remained somewhat shadowed by his introverted nature and the lingering disapproval of his family. He lived and worked in London for much of his career, maintaining studios in various locations, including Chelsea, known for its artistic community. While exhibiting regularly at the Royal Academy and other venues like the Birmingham Royal Society of Artists, he seems not to have been a prominent figure in London's social art scene. His shyness likely kept him on the periphery.

A significant turning point occurred around 1911-1912. Seeking perhaps a change of scenery, greater artistic freedom, or simply the authentic light and classical ambiance that permeated his canvases, Godward decided to move to Italy. He settled in Rome, renting a studio near the Villa Borghese, a location steeped in classical history and artistic inspiration. Crucially, he did not go alone. He travelled with one of his models, whose identity remains somewhat uncertain but whose presence was central to this Italian chapter.

This move, particularly the cohabitation with his model outside of marriage, caused a definitive rupture with his family back in England. Their sense of propriety was deeply offended, and it is famously recounted that they were so ashamed they cut his image out of family photographs and ceased all contact. This act of familial excision must have profoundly wounded the already sensitive artist, deepening his sense of isolation even amidst the beauty of Rome.

His time in Italy, which lasted nearly a decade until 1921, was artistically productive. The Mediterranean light and landscape infused his work, and Roman settings became more prominent. He continued to paint his signature subjects, finding inspiration in the local models and the classical ruins surrounding him. Works from this period often possess a heightened sense of warmth and colour, reflecting his direct immersion in the Italian environment. However, the underlying melancholy, perhaps exacerbated by his family's rejection, can sometimes be detected beneath the placid surfaces of his paintings.

The Shifting Tides of Art: Modernism's Rise

While Godward perfected his classical idylls in Rome, the art world back in London and across Europe was undergoing a seismic shift. The Academic tradition, with its emphasis on representational accuracy and historical themes, was being aggressively challenged by a succession of avant-garde movements. Post-Impressionism, spearheaded by artists like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, had already prioritized emotional expression and symbolic colour over naturalistic depiction.

The early 20th century saw the explosive arrival of Fauvism, led by Henri Matisse, with its bold, non-naturalistic colours, and Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, which fragmented form and revolutionized pictorial space. These movements, along with others like Futurism and early Abstraction, fundamentally questioned the very purpose and appearance of art. Representation, meticulous finish, and classical beauty – the cornerstones of Godward's practice – were increasingly seen as outdated, irrelevant, and bourgeois by the proponents of Modernism.

The critical tide turned decisively against artists like Godward, Alma-Tadema, and Leighton. Their work, once celebrated, was now often dismissed as sentimental, overly literal, and lacking in genuine artistic innovation. The horrors of World War I further accelerated this shift in taste, making idealized depictions of a serene classical past seem disconnected from the harsh realities of the modern world. For an artist like Godward, whose entire aesthetic was built on principles now deemed obsolete, this change was devastating.

Return to London, Despair, and Tragic End

In 1921, possibly due to declining health or a sense of growing irrelevance even in Rome, Godward returned to London. He found an art world transformed, one that had little interest in his meticulously crafted visions of classical beauty. His style was now thoroughly out of fashion, and commissions likely dwindled. The critical acclaim he had once enjoyed had evaporated, replaced by indifference or even scorn from the proponents of the new artistic order.

Compounding his professional disappointment was his enduring personal isolation. His family remained estranged, and his naturally shy and depressive temperament offered little resilience against the tide of artistic change and neglect. He reportedly became increasingly despondent. The world he understood, the artistic values he cherished, seemed to have vanished, leaving him adrift.

In December 1922, at the age of 61, John William Godward took his own life in his studio at Fulham Road, London. The method was reported as gas poisoning. According to widely circulated accounts, he left behind a suicide note that starkly expressed his sense of artistic displacement. It allegedly read: "The world is not big enough for myself and a Picasso." Whether apocryphal or not, the quote powerfully symbolizes the perceived clash between the fading Academic tradition Godward represented and the triumphant rise of Modernism embodied by Picasso. His family, adhering to their sense of propriety even in death, are said to have destroyed his papers, further obscuring the details of his final years and personal thoughts.

Posthumous Reputation and Legacy

Following his death, Godward's work, like that of many Victorian Academic painters, fell into deep obscurity for several decades. The dominant narrative of 20th-century art history, focused on the progression of Modernism, had little room for artists perceived as conservative traditionalists. His paintings were largely ignored by major museums and critically dismissed. Figures like Alma-Tadema, Leighton, Edward Poynter, and even the Pre-Raphaelites (such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt) suffered similar periods of neglect, though perhaps less profoundly than Godward.

However, beginning in the latter half of the 20th century, and accelerating into the 21st, there has been a significant reassessment of Victorian and Edwardian art. Art historians, curators, and collectors began to look beyond the modernist canon, recognizing the technical skill, aesthetic appeal, and historical significance of artists previously sidelined. Godward's work has benefited considerably from this revival of interest.

Today, John William Godward is recognized as one of the foremost painters of the late classical revival in Britain. His technical mastery, particularly in rendering textures like marble and fabric, is widely admired. His paintings are appreciated for their serene beauty, their evocative power, and their embodiment of a specific, albeit idealized, vision of antiquity. While his subject matter may seem limited to some, the consistency and quality of his execution are undeniable. His works now command high prices at auction and are sought after by collectors specializing in 19th-century European art. Museums, including the Getty Museum in Los Angeles which has a strong collection of related works by Alma-Tadema, now feature his paintings, acknowledging his place within the broader history of art.

Conclusion: Beauty and Tragedy

The life and art of John William Godward present a poignant paradox. His canvases depict a world of perfect calm, luminous beauty, and untroubled leisure, meticulously rendered with extraordinary technical skill. Yet, the artist himself lived a life marked by familial disapproval, personal isolation, professional displacement, and ultimately, profound despair. He was a master craftsman dedicated to an aesthetic ideal that was swept aside by the relentless march of Modernism.

As an art historian, one must appreciate Godward not as an innovator who changed the course of art, but as a superb exponent of a particular tradition – the late Victorian Neoclassical style heavily influenced by Leighton and Alma-Tadema. He perfected a vision of classical antiquity filtered through the lens of late 19th-century taste, emphasizing sensual beauty and technical polish over historical drama or intellectual depth. His dedication to this vision, even as the art world moved in a radically different direction, defines both his achievement and his tragedy. Today, his paintings endure as testaments to his remarkable skill and as captivating glimpses into a lost world of idealized beauty, securing his distinct, if specialized, place in the annals of art history. His work reminds us that artistic value can reside not only in revolution but also in the dedicated refinement of established forms.