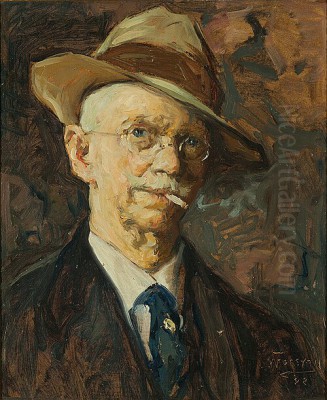

William Forsyth (1854-1935) stands as a pivotal figure in American Impressionism, particularly renowned for his role within the Hoosier Group of artists who brought a distinct Midwestern sensibility to the Impressionist movement. Born in Hamilton County, Ohio, on October 15, 1854, Forsyth's life and career became inextricably linked with Indiana after his family relocated to Indianapolis during his youth. His dedication to capturing the nuanced beauty of the Indiana landscape, combined with his influential career as an art educator, cemented his legacy as one of the most respected and beloved artists of his generation in the American Midwest.

Early Life and Artistic Stirrings

Forsyth's early years in Ohio were formative, but it was the move to Lafayette, Indiana, around 1864, and subsequently to Indianapolis, that set the stage for his artistic development. From a young age, he exhibited a keen interest in drawing and painting. His formal art education began tentatively at the first Indiana School of Art in Indianapolis, where he studied under Barton S. Hays, a prominent local portrait and landscape painter. However, financial constraints were a persistent challenge for the aspiring artist.

The economic realities of the time meant that Forsyth could not immediately dedicate himself solely to art. To support himself, he engaged in various occupations, including a period spent working with his brother, David, in a house painting business. This practical experience with paints and surfaces, though not fine art, likely provided him with a foundational understanding of materials. Despite these detours, his passion for art remained undiminished, and he continued to sketch and paint whenever opportunities arose, honing his skills through observation and practice.

His determination to pursue a professional art career was unwavering. He saved diligently, driven by the ambition to seek more advanced training, a common aspiration for American artists of that era who often looked to Europe, particularly Germany and France, for rigorous academic instruction. This period of his life was characterized by a quiet perseverance, laying the groundwork for the significant artistic contributions he would later make.

The Munich Sojourn: A Crucible of Development

In 1881, William Forsyth, along with his close friend and fellow Indiana artist Theodore Clement (T.C.) Steele, embarked on a journey that would profoundly shape his artistic trajectory: they traveled to Munich, Germany, to enroll in the prestigious Royal Academy of Fine Arts. Munich, at the time, was a major European art center, rivaling Paris in its appeal to international students, especially those from America. The Academy was known for its rigorous, traditional training methods, emphasizing draftsmanship, anatomy, and a dark, tonal palette characteristic of the Munich School.

At the Royal Academy, Forsyth studied under influential figures such as Ludwig von Löfftz and Nikolaos Gysis. These instructors instilled in him a strong technical foundation. During his time in Munich, he also associated with other American artists, including Frank Duveneck and William Merritt Chase, who had themselves been products of the Munich School and were becoming influential in American art. The "Duveneck Boys," a group of American artists studying with Duveneck in Munich and Italy, were known for their bravura brushwork and realistic portrayals, and their influence permeated the artistic environment.

Forsyth's years in Munich, which extended until 1886, were a period of intense study and artistic growth. He absorbed the technical discipline of the Academy but also began to explore the emerging trends towards plein air painting and a lighter palette, influences that were beginning to seep into even the more conservative art academies. His correspondence from this period reveals an artist deeply engaged with his studies, grappling with artistic challenges, and forming lasting bonds with fellow students, particularly Steele. This European experience was crucial, providing him with the skills and confidence to return to America as a mature artist.

Return to Indiana and the Genesis of the Hoosier Group

Upon his return to Indiana from Munich in the late 1880s, William Forsyth brought with him a wealth of European training and a refined artistic vision. He initially settled in Muncie, Indiana, where he taught art alongside J. Ottis Adams, another key figure who had also studied in Munich. This period marked the beginning of his long and influential career as an art educator in his home state.

The late 19th century saw the coalescence of a remarkable group of Indiana artists, many of whom had shared the experience of studying in Munich or Paris. Forsyth, T.C. Steele, J. Ottis Adams, Otto Stark (who studied in Paris), and Richard B. Gruelle (largely self-taught but aligned with the group's ideals) became the core members of what would be known as the Hoosier Group. This informal collective gained significant recognition following a joint exhibition in Chicago in 1894, titled "Five Hoosier Painters."

The Hoosier Group artists shared a common goal: to depict the unique character and beauty of the Indiana landscape. While their individual styles varied, they were united by their commitment to plein air painting and an Impressionistic approach to light and color, adapted to the specific atmospheric conditions and scenery of the Midwest. They sought to create an authentic regional art, moving away from purely academic or European subjects to find inspiration in their immediate surroundings. Forsyth was a passionate advocate for this vision, believing deeply in the artistic potential of his native state.

Forsyth's Artistic Style: Capturing the Hoosier Landscape

William Forsyth's artistic style is best characterized as a robust form of American Impressionism, deeply rooted in his academic training yet enlivened by a direct, personal response to nature. While he embraced the Impressionists' concern for light, color, and atmospheric effects, his work often retained a stronger sense of form and structure than that of some of his French counterparts like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro. His Munich training, with its emphasis on solid draftsmanship, remained an underlying component of his art.

Forsyth was particularly drawn to the varied landscapes of Indiana – its rolling hills, dense woodlands, winding rivers, and the changing light of its distinct seasons. He had a remarkable ability to capture the specific character of a place, whether it was the tranquil beauty of a sun-dappled creek, the starkness of a winter forest, or the vibrant hues of autumn foliage. His brushwork was often vigorous and expressive, conveying a sense of immediacy and a deep connection with his subject matter.

Unlike some Impressionists who dissolved form into shimmering light, Forsyth often used a more textured application of paint, building up surfaces that conveyed the materiality of the scenes he depicted. His palette, while lighter and more colorful than his early Munich work, could also incorporate the rich, earthy tones characteristic of the Indiana soil and vegetation. He was a master of capturing the subtle shifts in light and atmosphere, from the hazy humidity of a summer day to the crisp clarity of an autumn afternoon. His contemporaries, such as John Henry Twachtman or J. Alden Weir of the Ten American Painters, explored similar Impressionistic paths, but Forsyth's work remained distinctly "Hoosier" in its subject and sentiment.

Representative Works: A Testament to Indiana's Beauty

William Forsyth's oeuvre is rich with paintings that celebrate the Indiana landscape. Among his most well-known and representative works is "The Constitutional Elm, Corydon" (c. 1916). This painting depicts the historic elm tree under which Indiana's first state constitution was drafted. Forsyth imbues the scene with a sense of historical reverence, capturing the majestic tree with a play of light and shadow that highlights its enduring presence. The work is both a landscape and a piece of historical commemoration.

Another significant painting is "Autumn at Vernon," which showcases Forsyth's mastery of color and his ability to convey the specific atmosphere of an Indiana autumn. The rich reds, oranges, and yellows of the foliage are rendered with vibrant brushstrokes, and the composition leads the viewer's eye through a scene filled with the warm, hazy light typical of the season. Similarly, works like "Beechwoods in Winter" demonstrate his skill in capturing the more austere beauty of the landscape, using a cooler palette and focusing on the intricate patterns of bare branches against the snow.

"The Old Mills," often depicting structures along Indiana's rivers like the Whitewater or Muscatatuck, were recurring subjects for Forsyth. These paintings not only captured picturesque scenes but also hinted at the changing rural landscape and the passage of time. His depictions of creeks and rivers, such as "Brookville Landscape, Whitewater River Valley," are characterized by their fluid brushwork and sensitivity to the reflections and movement of water. These works, alongside those of his Hoosier Group colleagues like Steele's Brown County scenes or Adams's depictions of the Hermitage, collectively created a powerful visual identity for Indiana.

A Dedicated Educator: The Herron School of Art

Beyond his achievements as a painter, William Forsyth made an enduring contribution to art in Indiana through his long and dedicated career as an educator. In 1906, he joined the faculty of the John Herron Art Institute in Indianapolis (now the Herron School of Art and Design, part of Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis). He would remain a principal instructor there for nearly three decades, until his retirement in 1933.

Forsyth was a highly respected and influential teacher, known for his rigorous standards, his deep knowledge of art history and technique, and his passionate commitment to his students' development. He taught drawing and painting, emphasizing the importance of strong draftsmanship, direct observation from nature, and a thorough understanding of materials. His teaching philosophy was grounded in the academic traditions he had absorbed in Munich, but it was also informed by his own experiences as a plein air painter and his belief in the importance of individual expression.

He mentored generations of Indiana artists, many of whom went on to have successful careers of their own. His students remembered him as a demanding but fair instructor, one who pushed them to achieve their best while also offering encouragement and support. His influence extended beyond the classroom; as a prominent member of the Indianapolis art community, he actively participated in exhibitions, lectures, and arts organizations, tirelessly promoting art appreciation and education in the state. His role at Herron was comparable to that of other influential artist-teachers in America, such as Robert Henri at the Art Students League of New York or Thomas Eakins at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Relationships with Contemporaries: The Hoosier Brotherhood

William Forsyth's relationships with his fellow artists, particularly the members of the Hoosier Group, were central to his personal and professional life. His friendship with T.C. Steele was perhaps the most significant. Forged during their student days in Indianapolis and solidified during their shared experiences in Munich, their bond was one of mutual respect and artistic camaraderie, though not without its complexities. Forsyth, in his private writings, sometimes expressed a critical view of Steele's more commercially successful and, in Forsyth's opinion, occasionally less adventurous art. Nevertheless, their friendship endured, built on a shared passion for painting the Indiana landscape.

Forsyth also maintained close ties with J. Ottis Adams. They taught together in Muncie and later at the Herron Art Institute. Adams, like Forsyth and Steele, was a key figure in establishing an Impressionist-influenced landscape tradition in Indiana. Their shared European experiences and their commitment to regional art created a strong professional bond.

With Otto Stark and Richard B. Gruelle, the other core members of the Hoosier Group, Forsyth shared a collective identity that helped to elevate Indiana art to national attention. Stark, who had studied at the Académie Julian in Paris, brought a slightly different, perhaps more decorative, sensibility to his Impressionism. Gruelle, though largely self-taught, was a sensitive painter of atmospheric landscapes. Together, these artists supported each other, exhibited together, and collectively shaped the artistic landscape of Indiana for several decades. Their interactions were not unlike those seen in other regional art colonies or groups in America, such as the artists at Old Lyme, Connecticut, which included Childe Hassam and Willard Metcalf, or the Taos Society of Artists in New Mexico.

Forsyth's private letters and diaries offer valuable insights into these relationships, revealing the everyday concerns, artistic debates, and personal dynamics within this close-knit community of artists. He was known for his sometimes gruff demeanor and outspoken opinions, but also for his loyalty and dedication to his friends and to the cause of art in Indiana.

Challenges, Recognition, and Public Works

Like many artists, William Forsyth faced his share of challenges throughout his career. Financial insecurity was a recurring theme, especially in his early years. Even after establishing himself as a prominent artist and teacher, the art market could be unpredictable. He often supplemented his income from painting sales with his teaching salary from the Herron Art Institute.

The critical reception of Impressionism in America, and particularly in the more conservative Midwest, was initially mixed. While the Hoosier Group achieved significant regional acclaim and helped to popularize Impressionist aesthetics in Indiana, Forsyth and his colleagues were part of a broader movement that had to win acceptance against more established academic traditions. Forsyth's own style, sometimes more rugged and less conventionally "pretty" than that of some of his contemporaries, might have presented its own challenges in terms of broad popular appeal, though it was highly respected by connoisseurs and fellow artists for its honesty and strength.

Despite these challenges, Forsyth received considerable recognition during his lifetime. He won numerous awards and prizes at regional and national exhibitions. One notable achievement was his commission to create murals for the W.K. Stewart Company bookstore in Indianapolis, a significant public art project. Later in his career, during the Great Depression, he participated in the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), a New Deal initiative designed to employ artists. Two of his PWAP paintings, created for the Indiana State Library, are now housed in the collection of the Indiana State Museum, serving as a testament to his contribution to public art. These commissions provided not only financial support but also an opportunity to create art for a wider public audience.

Later Years, Anecdotes, and Enduring Legacy

In his later years, William Forsyth continued to paint and teach with undiminished passion, though his health began to decline. He retired from the Herron Art Institute in 1933, after nearly three decades of service. Anecdotes from this period paint a picture of a man deeply devoted to his art and his family. His daughters, Dorothy, Constance (also an artist and printmaker), and Alice, provided him with support and companionship. Even after a heart attack in 1934 weakened him, he reportedly made an effort to paint daily, often sitting outdoors, surrounded by the nature he loved.

One story often recounted is Forsyth's dedication to his craft even in the face of adversity. His persistence in pursuing art despite early financial struggles, and his continued commitment to painting even in old age and ill health, speak to the profound importance of art in his life. His home in the Indianapolis suburb of Irvington, where he lived for many years, became a haven for artists and art lovers, and he was a respected elder statesman of the Indiana art community.

William Forsyth passed away on March 29, 1935, in Indianapolis. His death marked the end of an era for Indiana art. He left behind a rich legacy as a painter and an educator. His paintings continue to be celebrated for their evocative portrayals of the Indiana landscape and are held in numerous public and private collections, including the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, the Indiana State Museum, and various university art galleries.

His influence as a teacher shaped generations of Indiana artists, and his role in the Hoosier Group was instrumental in establishing a vibrant regional art tradition. Artists like Wayman Adams (a portrait painter who studied with Forsyth), William Edouard Scott, and numerous others benefited from his instruction. Forsyth, along with Steele, Adams, Stark, and Gruelle, demonstrated that American artists could find profound inspiration in their own local environments, contributing significantly to the diversification and enrichment of American art in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His life and work remain an integral part of Indiana's cultural heritage and a significant chapter in the story of American Impressionism.