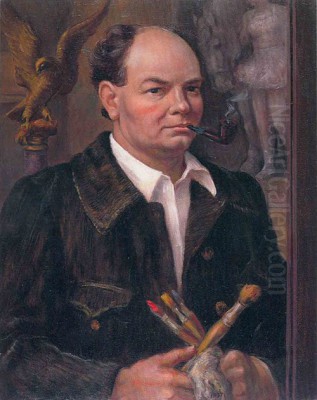

John Steuart Curry stands as a pivotal figure in 20th-century American art, celebrated primarily as one of the leading proponents of Regionalism. Alongside Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood, Curry formed the triumvirate that defined this uniquely American art movement during the 1920s and 1930s. His work is characterized by dramatic, often turbulent depictions of life in the American Midwest, particularly his native Kansas. Through powerful canvases exploring themes of nature, faith, struggle, and community, Curry sought to capture the essence of the American heartland, leaving behind a complex and enduring legacy. His life spanned a period of significant change in America, from the late 19th century into the tumultuous years leading up to and including World War II.

Born on November 14, 1897, near Dunavant, Jefferson County, Kansas, Curry's roots were deeply embedded in the rural landscape he would later immortalize. Raised on a farm, he experienced firsthand the rhythms of agricultural life, the close-knit nature of farming communities, and the awesome, sometimes destructive, power of nature on the Great Plains. This upbringing provided an inexhaustible source of inspiration and subject matter throughout his artistic career. His parents were devout Presbyterians, and the religious fervor and biblical narratives common in his household also profoundly shaped his worldview and artistic sensibilities.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Curry's early life on the farm instilled in him a deep connection to the land and its people. He witnessed the hard labor, the communal bonds, and the dramatic weather events – thunderstorms, floods, and tornadoes – that were part of everyday existence in Kansas. This direct experience lent an authenticity and emotional weight to his later paintings. His family encouraged his artistic inclinations from a young age. He was reportedly captivated by illustrations, particularly the dramatic biblical scenes rendered by the French artist Gustave Doré, whose influence can be discerned in the theatricality and emotional intensity of Curry's mature work.

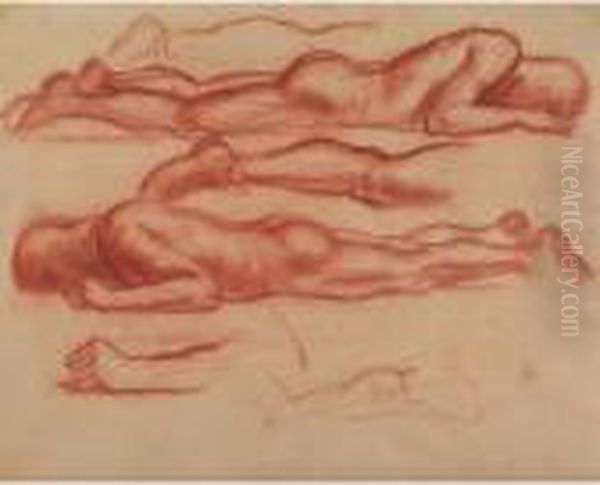

His formal art education began at the Kansas City Art Institute in 1916. He continued his studies at the Art Institute of Chicago from 1916 to 1918, where he worked under artists like Edward J. Timmons and John W. Norton. Following his time in Chicago, Curry briefly attended Geneva College in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania. Like many aspiring artists of his generation, he initially pursued a career in illustration to support himself. From 1921 to 1926, he worked prolifically for popular magazines such as Boys' Life, St. Nicholas Magazine, County Gentleman, and The Saturday Evening Post, honing his skills in narrative composition and figurative drawing.

Seeking broader artistic horizons, Curry traveled to Paris in 1926, enrolling at the Académie Julian and studying with the Russian academic painter Vasily Shukhayev. While abroad, he immersed himself in the European art tradition, studying the Old Masters in museums like the Louvre. He was particularly drawn to the dramatic compositions and emotional power of Baroque painters like Peter Paul Rubens and the Romantic energy of artists such as Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix. Though exposed to European Modernism, Curry remained largely committed to representational art, seeking to adapt traditional techniques to American subjects. His time in Paris solidified his technical skills but ultimately reinforced his desire to paint the world he knew best – the American Midwest.

Rise to Prominence and the Regionalist Movement

Upon returning to the United States in 1927, Curry settled in Westport, Connecticut, near New York City, but his artistic focus remained firmly fixed on his Midwestern roots. A pivotal moment came in 1928 with the exhibition of his painting Baptism in Kansas at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. This powerful work, depicting a rural immersion baptism ceremony with characteristic intensity and dramatic flair, garnered significant critical attention. It was praised for its authentic portrayal of American life and its departure from European artistic conventions. The painting was subsequently purchased by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, a major patron of American art and founder of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Baptism in Kansas effectively launched Curry's career as a serious painter and positioned him at the forefront of the emerging Regionalist movement. Regionalism gained traction during the late 1920s and the Great Depression of the 1930s, partly as a reaction against European abstract art and partly as a nationalistic impulse to define a distinctly American artistic identity. The movement celebrated rural life, local customs, and the landscapes of the American heartland, often portraying themes of resilience, community, and hard work in the face of adversity.

Curry, along with Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri and Grant Wood of Iowa, quickly became identified as the leading figures of Regionalism. While sharing a common focus on American themes and a commitment to representational art, each artist possessed a unique style. Benton was known for his dynamic, swirling compositions and elongated figures; Wood developed a highly stylized, meticulous approach often imbued with gentle satire; Curry's work was distinguished by its raw emotional power, dramatic action, and sympathetic portrayal of human struggle against the forces of nature and societal challenges. Together, they captured the public imagination and enjoyed widespread popularity during the 1930s, championed by critics like Thomas Craven and Peyton Boswell Jr., editor of Art Digest.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

John Steuart Curry's artistic style is a compelling blend of realism, drama, and emotional expression. He employed robust, often muscular figures, dynamic compositions frequently built on diagonals or swirling vortexes, and a rich, earthy color palette. His brushwork could be vigorous and expressive, contributing to the sense of energy and movement that pervades many of his best works. He possessed a keen sense for narrative, often choosing moments of peak action or intense emotion to depict. Influences from Baroque masters like Rubens and Rembrandt are evident in his dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) and the sheer physicality of his figures.

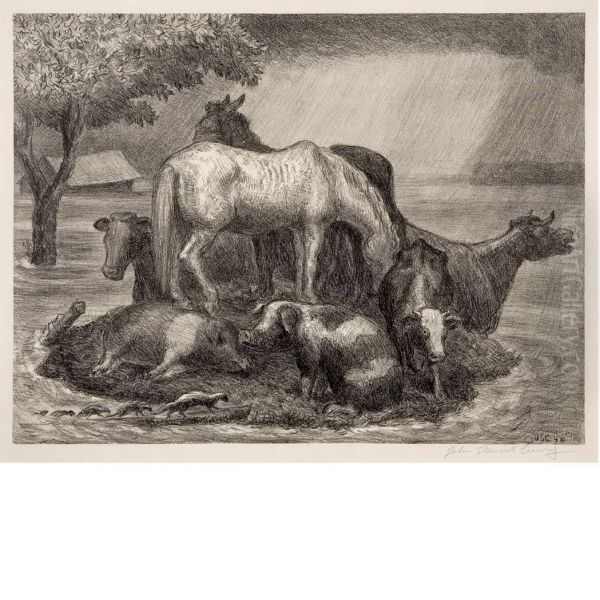

Curry's primary thematic concerns revolved around the life and landscape of the American Midwest. He painted scenes of everyday farm labor, capturing the toil and dignity of agricultural work. Works like Hogs Killing a Rattlesnake (c. 1930) present the brutal realities of nature with unflinching honesty. He was particularly drawn to the power and spectacle of nature, most famously depicted in Tornado Over Kansas (1929), where a farm family rushes to a storm cellar as a menacing funnel cloud dominates the sky. This painting became an iconic image of life on the plains, symbolizing both the vulnerability and resilience of its inhabitants. Other works, like The Line Storm (1934), similarly convey the awe-inspiring and often threatening aspects of the Midwestern climate.

Religion and community were also central themes. Baptism in Kansas explores communal faith, while his later murals featuring the abolitionist John Brown delve into themes of religious fanaticism, social justice, and violence. Curry did not shy away from depicting hardship and struggle, whether it was the farmer battling the elements, the community facing natural disaster, or the nation grappling with its history of conflict and social division. His approach was generally sympathetic, portraying his subjects with dignity even in moments of intense stress or turmoil. Unlike Wood's sometimes satirical view, Curry's perspective was typically more earnest and empathetic.

Major Works and Commissions

Beyond his early breakthrough paintings, Curry produced a significant body of work throughout the 1930s and early 1940s. Tornado Over Kansas (1929) remains one of his most recognized and frequently reproduced images, capturing the primal fear and drama of prairie storms. Hogs Killing a Rattlesnake (c. 1930) is another powerful, albeit disturbing, depiction of the violence inherent in the natural world, rendered with characteristic energy. These works cemented his reputation for capturing the raw, untamed aspects of Midwestern life.

During the New Deal era, Curry, like many artists including Benton, Wood, Ben Shahn, and Reginald Marsh, received commissions for public murals through government programs like the Treasury Section of Painting and Sculpture and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). He created murals for the Department of Justice Building (1936-1937) and the Department of the Interior Building (1937-1939) in Washington, D.C. The Justice Department murals, titled Movement of the Population Westward and Law Versus Mob Rule, depict themes relevant to American history and justice. The Interior Department mural, The Oklahoma Land Rush and The Homesteading, portrays pioneers claiming land, again touching on themes of settlement and struggle. These large-scale works allowed Curry to explore historical narratives on a grand stage.

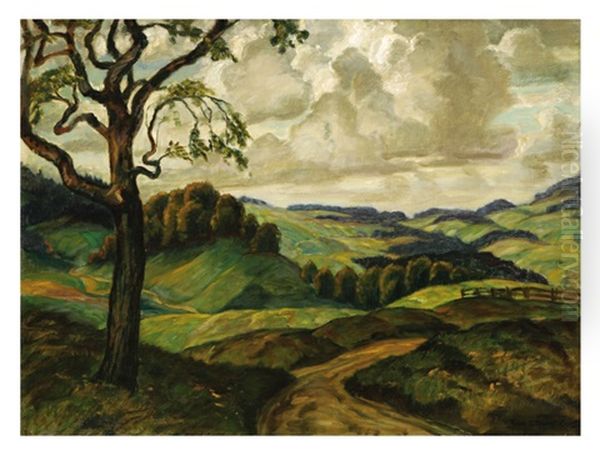

His easel paintings continued to explore familiar themes. The Line Storm (1934) is a masterful depiction of an approaching storm, showcasing his ability to render atmospheric effects and convey a sense of impending drama. Wisconsin Landscape (1938-1939), painted during his time as artist-in-residence, reflects his engagement with his adopted state's scenery, demonstrating a slightly more lyrical quality compared to some of his more turbulent Kansas scenes. Throughout his career, Curry consistently returned to the subjects that defined his artistic identity: the land, the people, and the elemental forces shaping life in the American heartland.

The Kansas State Capitol Murals Controversy

Perhaps the most ambitious and ultimately controversial project of Curry's career was the commission to paint murals for the Kansas State Capitol building in Topeka, begun in 1937. Curry envisioned a grand cycle depicting the history and spirit of Kansas. He planned panels for the east and west wings of the second-floor rotunda, focusing on themes of settlement, agriculture, and significant historical figures. The most famous and contentious of these planned murals was Tragic Prelude, intended for the east wing. This powerful composition centers on a towering, almost messianic figure of the abolitionist John Brown, flanked by Union and Confederate soldiers, symbolizing the Bleeding Kansas era and the turmoil leading up to the Civil War. Storm clouds and a tornado loom in the background, adding to the sense of conflict and impending doom.

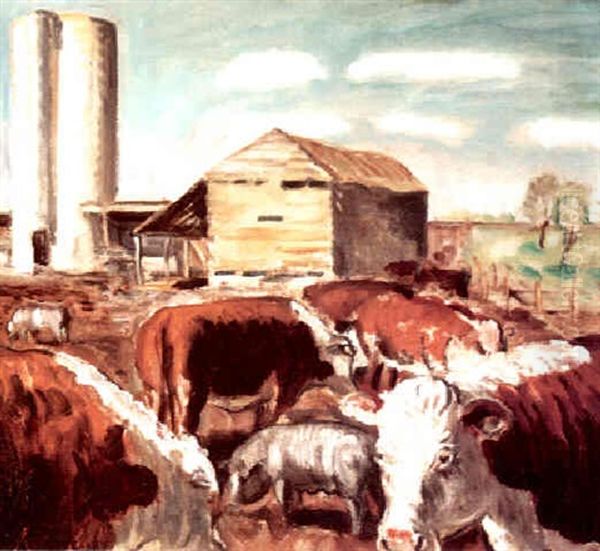

Another major panel, Kansas Pastoral, depicted the more idyllic aspects of the state: a farmer with his family, livestock, and the bounty of the land under a sunny sky. However, even this seemingly benign scene drew criticism. Some Kansans objected to details like the farmer's overalls, the depiction of a Hereford bull considered by some to be imperfect, and the prominence given to hogs. More significantly, the Tragic Prelude panel ignited fierce debate. Critics felt the depiction of John Brown was overly menacing and that the overall portrayal of Kansas history focused too much on violence and natural disasters, rather than presenting a purely positive image of the state. A legislative committee, the "Kansas Committee for Art Appreciation," was formed, and opposition mounted.

Frustrated by the criticism, the political interference, and a legislative decision to remove marble panels from the rotunda that Curry felt were essential for the murals' completion and aesthetic integrity, he ceased work on the project in 1942. He refused to sign the murals that were already painted on the walls, feeling the project was compromised and incomplete. The murals remain in the State Capitol today, unsigned and technically unfinished according to the artist's full vision, a testament to the often-difficult relationship between public art, politics, and regional identity. The controversy deeply wounded Curry and contributed to his complex feelings about his home state.

Life and Work in Wisconsin

In 1936, Curry accepted a unique position as the first artist-in-residence at the College of Agriculture at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. This role, conceived by Dean Chris L. Christensen, was intended to foster art appreciation and practice among rural communities and agricultural students. It provided Curry with financial stability and a supportive academic environment, away from the sometimes harsh criticism he faced in Kansas and the competitive New York art world. He remained in this position until his death in 1946.

During his decade in Wisconsin, Curry was an influential teacher and mentor. He traveled throughout the state, giving lectures, judging local art shows, and encouraging amateur artists. He played a key role in developing the Wisconsin Rural Art Program, which aimed to nurture artistic talent in rural areas and culminated in an annual exhibition of rural art. His presence significantly boosted the arts scene in Wisconsin and demonstrated a commitment to making art accessible beyond major urban centers.

His own painting continued during this period, often reflecting his new surroundings. Works like Wisconsin Landscape show his engagement with the gentler, more pastoral scenery of his adopted state. He also continued to explore themes relevant to agricultural life, sometimes specific to Wisconsin's dairy industry. His position allowed him the freedom to pursue his artistic interests while actively contributing to the cultural life of the state. His tenure in Wisconsin is remembered as a productive and influential period, highlighting his dedication not only to creating art but also to fostering it within the community.

The Circus Paintings

Alongside his depictions of rural life and historical events, John Steuart Curry developed a significant body of work focused on the circus. His fascination began in the early 1930s, and in 1932, he traveled for several months with the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, sketching performers, animals, and behind-the-scenes activities. This experience resulted in a series of vibrant and dynamic paintings and prints that capture the spectacle, danger, and athleticism of circus life.

Works like The Flying Codonas (c. 1932) depict the breathtaking skill and peril of trapeze artists, rendered with Curry's characteristic energy and dramatic composition. Circus Elephants (c. 1932) captures the massive presence and exoticism of these animals within the circus environment. The Passing Leap (1932) portrays the daring feats of equestrian performers. Curry seemed drawn to the intense physicality, the coordinated teamwork, and the inherent drama of the circus, themes that resonated with his interest in depicting action and human endeavor.

His circus paintings offer a different perspective on American life compared to his rural scenes, focusing on entertainment, transient communities, and extraordinary physical prowess. These works demonstrate his versatility as an artist and his ability to find compelling subject matter beyond the farm and prairie. Like other artists fascinated by the circus, such as Edgar Degas, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and Alexander Calder, Curry found in it a microcosm of human drama, skill, and spectacle, which he translated into powerful visual statements.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Curry's career unfolded within a vibrant and sometimes contentious American art scene. His most significant professional relationships were with his fellow Regionalists, Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood. Together, they formed the public face of the movement, often exhibiting together and sharing a commitment to American subject matter. While they respected each other's work, their personal relationship was not always close, and stylistic differences were apparent. Their dealer, Maynard Walker, played a crucial role in promoting their work through his gallery in New York.

Curry also maintained connections with other figures in the arts and letters. He had a friendship with William Allen White, the influential editor of the Emporia Gazette in Kansas, who was a supporter of his work. His collaboration with the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Sidney Howard on the play Alien Corn (1933), for which Curry provided illustrations, demonstrates his engagement with other creative fields. He was also acquainted with fellow artists like Reginald Marsh, known for his depictions of urban life, suggesting Curry's awareness of broader trends in American scene painting, even if his own focus remained primarily rural.

His interactions were not limited to the art world elite. His role in Wisconsin brought him into contact with numerous local artists and community members. However, his relationship with critics and the public, particularly in Kansas, was often strained, as evidenced by the State Capitol mural controversy. Despite achieving national fame, Curry remained sensitive to criticism and deeply invested in the reception of his work, especially concerning its portrayal of the Midwest he knew so intimately. Other artists of the period, like Charles Burchfield or Edward Hopper, also focused on American scenes but were generally less tied to the specific ideology of Regionalism.

Influences On and By Curry

John Steuart Curry's art was shaped by a variety of influences. His early exposure to Gustave Doré's dramatic illustrations left a lasting impact on his narrative style. His academic training and study of Old Masters in Europe, particularly Baroque artists like Rubens and Rembrandt, informed his use of dynamic composition, chiaroscuro, and robust figuration. The energy and emotionalism of Romantic painters like Géricault and Delacroix also find echoes in his work. American predecessors like Winslow Homer, with his focus on American life and the power of nature, may also have served as an inspiration.

Within the Regionalist movement, Curry, Benton, and Wood undoubtedly influenced each other, creating a dialogue around American themes even as their styles diverged. Curry's unique contribution was his emphasis on raw emotion, action, and the often-turbulent relationship between humans and their environment.

Curry, in turn, exerted influence, particularly through his teaching and advocacy. As artist-in-residence in Wisconsin, he directly mentored and encouraged a generation of rural artists, fostering a grassroots art movement. While the dominance of Abstract Expressionism after World War II, championed by artists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, overshadowed Regionalism, Curry's work remained significant. Later artists interested in narrative painting, American history, or regional identity, such as perhaps Peter Hurd or even aspects of Andrew Wyeth's work (though stylistically distinct), might find resonance in Curry's commitment to specific locales and human stories. His public murals also contributed to the tradition of large-scale narrative art in America, influencing subsequent muralists.

Legacy and Critical Reception

John Steuart Curry's reputation has experienced fluctuations since his death on August 29, 1946, at the relatively young age of 48. During the 1930s, he was among America's most celebrated painters, lauded for his authentic portrayal of the nation's heartland and his powerful, accessible style. However, with the rise of Abstract Expressionism and subsequent modernist movements in the post-war era, Regionalism fell out of critical favor. Curry and his peers were sometimes dismissed as provincial, illustrative, or overly sentimental, resistant to the progressive trends of international art. Critics argued that his focus on narrative and recognizable subject matter was outmoded.

Despite this decline in critical standing during the mid-20th century, Curry's work never entirely disappeared from view. His paintings remained popular with the public and held significant places in major museum collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City. His iconic images, particularly Tornado Over Kansas and Baptism in Kansas, continued to be reproduced and recognized as defining images of a particular era and region of American experience.

In more recent decades, there has been a reassessment of Regionalism and Curry's contribution. Art historians now recognize the movement's importance in reflecting American culture during a specific historical period (the Depression and pre-war years) and acknowledge the technical skill and emotional power inherent in Curry's work. While criticisms regarding melodrama or resistance to modernism persist in some quarters, his paintings are increasingly appreciated for their dramatic intensity, their sincere engagement with American life, and their complex exploration of themes like nature, faith, and social history. He is firmly established as a major figure in 20th-century American art, particularly for his role in defining Regionalism and for creating enduring images of the Midwestern experience.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of the Heartland

John Steuart Curry's art provides a powerful and often unsettling window into the American Midwest of the early 20th century. Rooted in his Kansas upbringing, his work transcends mere illustration to offer dramatic, emotionally charged visions of rural life, natural forces, and historical moments. As a key figure in the Regionalist movement, alongside Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood, he helped shape a distinctly American art focused on local themes and experiences during a period of national introspection.

His style, marked by dynamic compositions, robust figures, and a flair for the dramatic, captured both the hardships and the resilience of heartland communities. From the communal fervor of Baptism in Kansas to the terrifying power of Tornado Over Kansas and the controversial historical narrative of the John Brown murals, Curry tackled significant themes with honesty and intensity. His work with the circus revealed another facet of his interest in spectacle and human endeavor, while his tenure in Wisconsin highlighted his commitment to fostering art beyond metropolitan centers.

Though his critical fortunes waned with the rise of modernism, John Steuart Curry's legacy endures. His paintings remain compelling visual documents of American life and potent explorations of the human condition in the face of nature's power and societal challenges. He stands as a vital chronicler of the American heartland, an artist whose dramatic vision continues to resonate with viewers today.