William Heath Robinson stands as a unique and beloved figure in the annals of British art and illustration. More than just an artist, he became a cultural icon, his very name entering the English language as an adjective to describe any comically over-engineered and unnecessarily complex machine designed to perform a simple task. As an art historian, to delve into the world of Heath Robinson is to explore a realm where meticulous draughtsmanship meets whimsical absurdity, where the mundane is transformed into the marvellously mechanical, and where a gentle, pervasive humour critiques and celebrates the human condition in an age of rapid technological change.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born on May 31, 1872, in Stroud Green, North London, William Heath Robinson was destined for a life in art. He hailed from a family линия (lineage) steeped in creative pursuits; his father, Thomas Robinson, was an engraver and illustrator, and his elder brothers, Thomas Heath Robinson (known as Tom) and Charles Robinson, also became successful illustrators. This familial environment undoubtedly nurtured his nascent talents and provided a practical understanding of the illustration profession from an early age. The Robinson household, while not affluent, was reportedly a happy one, fostering the imaginative spirit that would later define his work.

His formal artistic education began at the Islington School of Art, followed by a brief stint at the Royal Academy Schools. Initially, Heath Robinson harboured ambitions of becoming a serious landscape painter, a path trodden by many aspiring artists of his generation, perhaps dreaming of emulating the atmospheric works of masters like J.M.W. Turner or the detailed naturalism of the Pre-Raphaelites. However, the pragmatic need to earn a living soon steered him towards the more commercially viable field of book illustration, a domain where his brothers were already making their mark. This shift, born of necessity, would ultimately lead him to his true calling and lasting fame.

The Dawn of a Unique Vision: Early Illustrations

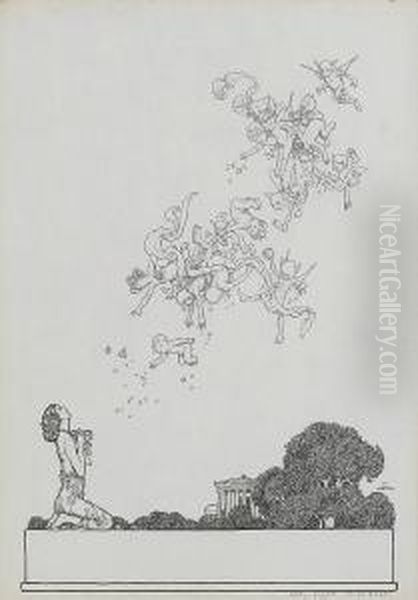

Heath Robinson's early illustrative work, emerging in the late 1890s and early 1900s, bore the stylistic hallmarks of the prevailing Art Nouveau movement. This is evident in the sinuous lines, decorative patterns, and often ethereal quality found in his illustrations for works such as The Poems of Edgar Allan Poe (1900), Don Quixote (1902), and Hans Christian Andersen's Danish Fairy Tales and Legends (1897), a project he collaborated on with his brothers Tom and Charles. These early pieces showcased his technical skill and a romantic sensibility, aligning him with contemporaries like Aubrey Beardsley, whose decorative black and white work had a profound impact, and Charles Ricketts, another influential figure in book design and illustration.

His illustrations for Rabelais' Gargantua and Pantagruel (1904) began to hint at the grotesque humour and inventive detail that would later become his signature. While still demonstrating a mastery of traditional pen-and-ink techniques, these works showed a burgeoning interest in the comical and the exaggerated. He was working within the "Golden Age of Illustration," a period that saw a flourishing of talent and a high demand for illustrated books, with artists like Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac producing sumptuously illustrated gift books that captivated the public. Heath Robinson was part of this vibrant scene, yet he was steadily carving out his own distinct niche.

The Birth of the "Heath Robinson Contraption"

The true turning point in Heath Robinson's career, and the foundation of his enduring legacy, was the development of his iconic humorous drawings depicting absurdly complex mechanical contraptions. These inventions, meticulously rendered with an engineer's precision yet conceived with a jester's wit, were designed to perform ludicrously simple tasks – peeling a potato, waking a person from sleep, or testing the freshness of an egg – through an elaborate series of pulleys, levers, ropes, steam boilers, and often bewildered-looking human operators.

His first major foray into this genre was The Adventures of Uncle Lubin (1902), a children's book he both wrote and illustrated. This charming tale, chronicling Uncle Lubin's fantastical efforts to rescue his nephew from a Moon-Bag, was filled with the prototypical Heath Robinson machines. The book was a success and established his reputation as an artist of extraordinary comic inventiveness. Other notable works in this vein included Bill the Minder (1912) and Peter Quip in Search of a Friend (1922). These contraptions were not merely funny; they were a gentle satire on the increasing mechanisation of modern life, a playful commentary on humanity's often over-complicated solutions to simple problems. The term "Heath Robinson contraption" soon became common parlance in Britain, a testament to the widespread appeal and recognition of his unique style. This phenomenon found a parallel in the United States with the "Rube Goldberg machines," created by the American cartoonist Rube Goldberg, whose work shared a similar spirit of elaborate, impractical invention.

Illustrating the Classics and Commercial Ventures

Alongside his humorous mechanical drawings, Heath Robinson continued to produce exquisite illustrations for classic literature. His interpretations of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream (1914) and Twelfth Night (1908) are particularly noteworthy, showcasing a delicate fantasy and a keen sense of character. These works stand comparison with the best of his contemporaries, such as the aforementioned Arthur Rackham, whose fairy tale illustrations were legendary, or Kay Nielsen, a Danish illustrator known for his elegant and often melancholic Art Nouveau style, particularly in works like East of the Sun and West of the Moon. Heath Robinson also illustrated editions of The Water-Babies by Charles Kingsley and numerous other children's books and collections of fairy tales.

His versatility extended to commercial art and advertising. He created numerous humorous advertisements for various companies, applying his signature style to promote products with a wink and a nod. These campaigns were highly effective, leveraging his popular appeal. He also contributed prolifically to magazines like The Sketch, The Tatler, and The Bystander, where his cartoons reached a wide audience and further cemented his reputation as "The Gadget King." His ability to blend artistic skill with commercial savvy was a hallmark of his successful career.

A Master of Humour and Gentle Satire

The humour in Heath Robinson's work is typically gentle, whimsical, and quintessentially British. It often pokes fun at human foibles, bureaucratic absurdities, and the earnest but often misguided efforts of inventors and enthusiasts. His characters, frequently balding, bespectacled men in overalls or slightly stuffy middle-class gentlemen, approach their bizarre tasks with an endearing seriousness, which only heightens the comedy. There's a sense of innocent delight in the complexity itself, a celebration of ingenuity even when it's hilariously misapplied.

His satire, while present, rarely carried a bitter edge. Instead, it was an affectionate critique of the modern world's obsession with efficiency and technology, often highlighting the charming inefficiency that resulted. He captured the spirit of an era grappling with industrialisation and the rapid pace of technological advancement, offering a humorous lens through which to view these changes. His work resonated deeply with a public that was both fascinated by and slightly wary of the new mechanical age. This gentle approach distinguished him from more biting satirists of the period, such as the political cartoonists who often employed a sharper, more aggressive style.

Wartime Contributions: Morale and Machinery

During the First World War, Heath Robinson's unique talents were put to patriotic use. He created a series of cartoons depicting outlandish and comically impractical secret weapons and devices supposedly being developed by both the Allies and the Germans. These included contraptions for "Testing the Strength of Barbed Wire Entanglements," "A Mobile Bayonet-Proof Sentry Box," or "The New German Sausage-Trap." These drawings, widely published, provided much-needed comic relief during a grim period and were immensely popular, significantly boosting morale on the home front and among the troops. His ability to find humour even in the context of war, without trivialising the conflict, was a remarkable achievement.

His contributions during the Second World War took on a more direct, albeit still characteristically inventive, form. He was reportedly involved with the codebreakers at Bletchley Park. While he didn't design the Colossus computers themselves, some of the complex electro-mechanical machinery used in the code-breaking process, particularly elements of the "Robinson" machines (so named in tribute to his style of complex gadgetry), were said to have been inspired by his drawings or even benefited from his conceptual thinking. This connection, linking his fantastical inventions to real-world, high-stakes technology, adds another fascinating layer to his story. His wartime work, in both conflicts, demonstrated the power of humour and art to serve a national purpose.

Collaborations and Artistic Circles

Heath Robinson's career was intertwined with those of his contemporaries, not least his own brothers. The Robinson brothers often collaborated on early projects, sharing a studio and influencing each other's styles before each developed their more distinct artistic personalities. Charles Robinson, for instance, became known for his delicate and charming illustrations for children's books, often with a whimsical, fairy-tale quality reminiscent of artists like Jessie M. King. Tom Robinson also had a successful career as an illustrator.

Beyond his family, Heath Robinson was part of the broader community of illustrators and artists in London. He was one of the twenty illustrators profiled by Percy V. Bradshaw in his influential series The Art of the Illustrator (1917-1918), which provided insights into the working methods of leading artists of the day. This publication placed him alongside figures like Frank Reynolds, known for his Punch cartoons, and Harry Rountree, celebrated for his animal illustrations. While his style was highly individual, he operated within a thriving ecosystem of graphic artists, each contributing to the rich visual culture of the period. His unique approach, however, set him apart, making him less of a direct competitor and more of a cherished eccentric within the field. One could also consider the influence of earlier graphic humorists like George Cruikshank, whose detailed and often satirical etchings prefigured some aspects of Robinson's crowded, busy compositions.

Anecdotes and Personal Glimpses

Behind the public persona of the "Professor of Absurdity" was a dedicated family man and a hardworking artist. He married Josephine Latey in 1903, and they had five children. The family lived for a period in Pinner, Middlesex, where a museum dedicated to his work, the Heath Robinson Museum, now stands. Anecdotes suggest a man with a quiet sense of humour and a deep commitment to his craft. It's said he would often work late into the night in his studio, meticulously bringing his fantastical creations to life.

One interesting, though perhaps apocryphal, story relates to his supposed inability to perform simple household repairs, despite his fame for designing complex machinery. This adds a layer of charming irony to his public image. He was also known for his modesty. Despite the immense popularity of his "contraptions," he continued to value his more "serious" illustrative work, such as his Shakespearean illustrations, some of which, due to publishing challenges, remained unpublished during his lifetime. These personal details paint a picture of an artist who, while celebrated for his humour, also possessed a deep artistic sensibility and a dedicated work ethic.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

William Heath Robinson passed away on September 13, 1944, but his legacy is far-reaching and continues to thrive. His most significant contribution is undoubtedly the term "Heath Robinson," which remains a widely understood descriptor for any comically complex and Rube Goldberg-esque device. This linguistic immortality is a rare honour for an artist and speaks volumes about the cultural impact of his work. His drawings are instantly recognizable and continue to delight new generations with their blend of ingenuity and absurdity.

His influence can be seen in the work of later humorists, cartoonists, and even filmmakers. The intricate, comically flawed inventions in Aardman Animations' Wallace & Gromit series, created by Nick Park, owe a clear debt to Heath Robinson's vision. The kinetic sculptures of artists like Rowland Emett, famous for his whimsical machines including those in the film Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, also share a kindred spirit with Robinson's contraptions. Furthermore, contemporary designers and inventors, such as Thomas Heatherwick, have acknowledged his influence, particularly the playful approach to problem-solving and the celebration of intricate mechanisms.

Museums and collections preserve his work, and his books are still reprinted, ensuring that his unique artistic voice remains accessible. The Heath Robinson Museum in Pinner plays a crucial role in celebrating his life and art, showcasing the breadth of his output, from early watercolours and serious illustrations to his famous cartoons and advertising work. His art reminds us of the joy of invention, the humour in human endeavour, and the enduring appeal of a well-crafted absurdity. He was more than an illustrator; he was a social commentator, a humorist, and a visionary of the delightfully impractical. His work continues to inspire laughter and admiration, securing his place as one of Britain's most original and cherished artists, standing alongside other great British illustrators and humorists like Ernest H. Shepard of Winnie the Pooh fame, or the satirical genius of William Hogarth from an earlier era, who also used art to comment on society, albeit with a much sharper bite.

Conclusion: An Enduring Professor of Whimsy

William Heath Robinson's journey from an aspiring landscape painter to the "Professor of Absurdity" is a testament to his unique genius and his ability to tap into a particular vein of British humour. His meticulously drawn, hilariously complex contraptions became his trademark, offering a playful critique of an increasingly mechanized world while simultaneously celebrating the eccentricities of human ingenuity. He was a master draughtsman, a fertile inventor of the absurd, and a gentle satirist whose work brought joy and laughter to millions, especially during times of national hardship.

His legacy extends far beyond the pages of the books and magazines he illustrated. It lives on in the language, in the continued appreciation of his art, and in the inspiration he provides to subsequent generations of artists and creators. In a world that often takes itself too seriously, the enduring appeal of Heath Robinson's work lies in its ability to make us smile, to marvel at the ridiculous, and to appreciate the profound charm of the utterly impractical. He remains a beloved figure, a true original whose art continues to resonate with its timeless humour and imaginative flair, a unique star in the constellation of artists that includes such diverse talents as the fantastical illustrator John Tenniel of Alice in Wonderland fame and the sharp social observer Phil May.