William Henry Dethlef Koerner stands as a pivotal figure in the Golden Age of American Illustration, an artist whose vibrant canvases brought the narratives of the American West to life for millions of readers. Born in Lunden, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, on November 19, 1878, Koerner's destiny was intertwined with the American experience from a young age. His family emigrated to the United States in 1880, settling in Clinton, Iowa, a setting far removed from the dramatic Western landscapes he would later masterfully depict. Koerner's prolific career, spanning the early decades of the 20th century until his death on August 11, 1938, left an indelible mark on popular culture, particularly through his extensive work for publications like The Saturday Evening Post.

Early Life and Artistic Stirrings

Growing up in the American Midwest, young Koerner displayed an early aptitude for art. His formal artistic journey began not in prestigious academies, but in the practical, demanding world of newspaper illustration. He secured a position at the Chicago Tribune at the remarkably young age of fifteen, quickly learning the ropes of visual storytelling under deadline pressure. His talent was evident, and he rose through the ranks, eventually serving as an assistant art editor. This early experience in the fast-paced environment of a major newspaper undoubtedly honed his skills in composition, narrative clarity, and rapid execution – qualities that would serve him well throughout his illustration career.

Despite his success in Chicago, Koerner harbored ambitions beyond newspaper work. He sought more formal training to refine his technique and broaden his artistic horizons. This led him to relocate to New York City, the epicenter of the American publishing and art world at the time. There, he enrolled at the prestigious Art Students League, immersing himself in a more structured educational environment between 1905 and 1907. This period was crucial for his development, exposing him to new ideas, techniques, and a community of aspiring artists.

The Wilmington Experience: Under the Wing of Howard Pyle

While studying in New York, Koerner's peers recognized his potential and encouraged him to apply to a highly selective and influential program: Howard Pyle's School of Illustration in Wilmington, Delaware. Howard Pyle was more than just an instructor; he was a towering figure in American illustration, a master storyteller in paint, and a mentor who shaped an entire generation of iconic artists. Acceptance into Pyle's fold was a significant achievement and a turning point in Koerner's life and career.

From 1905 to 1907, Koerner absorbed Pyle's teachings alongside a remarkable group of fellow students who would also achieve great fame. This cohort included talents such as N.C. Wyeth, renowned for his dramatic illustrations for classic novels; Frank Schoonover, another master of adventure and historical scenes; Harvey Dunn, who would become an influential teacher himself; Stanley Arthurs; George Harding; Thornton Oakley; and Allen Tupper True, among others. The atmosphere Pyle cultivated was one of intense dedication, emphasizing historical accuracy, dramatic composition, and the importance of emotionally connecting with the subject matter – essentially "living" the illustration.

Pyle's influence on Koerner was profound and multifaceted. He instilled a strong work ethic, a commitment to research, and a powerful narrative sensibility. Perhaps most significantly, Pyle introduced Koerner and his classmates to the "broken color" technique. This approach, derived in part from Impressionism but adapted for the demands of illustration, involved applying strokes of relatively pure color side-by-side, allowing the viewer's eye to blend them optically. This created a sense of vibrancy, light, and immediacy that perfectly suited the dynamic scenes Koerner would come to specialize in. He also learned what some termed "commercial impressionism," adapting fine art techniques for the reproductive needs of magazines.

Forging a Career: The Saturday Evening Post and Beyond

Armed with the skills and philosophy imparted by Pyle, Koerner established his own studio in Wilmington in 1907. His talent quickly found a market in the burgeoning magazine industry. The early 20th century was a period of unprecedented growth for periodicals, fueled by advances in printing technology and a growing literate public hungry for stories and images. Magazines like The Saturday Evening Post, Collier's, McCall’s, Good Housekeeping, and Ladies' Home Journal commanded massive circulations and relied heavily on compelling illustrations to draw readers in.

Koerner soon became a favored contributor, particularly for The Saturday Evening Post, arguably the most influential magazine of its era. His ability to capture action, drama, and the rugged spirit of adventure made him an ideal choice for illustrating the Western stories that were immensely popular with the Post's readership. Over his career, Koerner would create more than 250 illustrations for the Post alone, visually defining countless tales of cowboys, pioneers, and the frontier. His work also graced the pages and covers of numerous other publications, cementing his reputation as one of the leading illustrators of his day.

His output was prodigious. Beyond the magazine illustrations, Koerner was a dedicated painter, producing over 500 finished paintings during his career. While many were created as illustrations, others were more personal works. He approached each assignment with meticulous care, often creating detailed preliminary sketches and studies to ensure accuracy and compositional strength. His studio was reportedly filled with Western props – saddles, firearms, clothing – which he used to lend authenticity to his scenes.

The Lure of the West: Subject Matter and Style

While Koerner illustrated a variety of subjects, he became most famous for his depictions of the American West. This was not the West of direct, contemporary experience for Koerner, but rather the West of history and imagination, fueled by popular fiction and a national fascination with the frontier narrative. He immersed himself in the genre, undertaking research trips to gather visual information and absorb the atmosphere of the landscapes he painted, although specific details of these trips are not always well-documented.

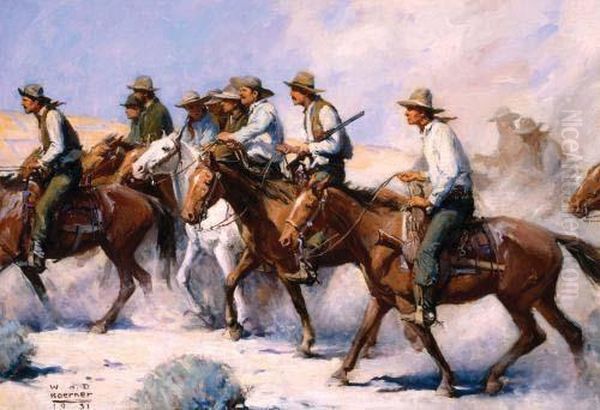

Koerner's West was a place of high drama, vast landscapes, and resilient characters. His canvases often feature dynamic compositions, using strong diagonals and contrasting light and shadow to heighten the sense of action and tension. Whether depicting a thundering cattle drive, a tense standoff, or a solitary pioneer family braving the elements, his illustrations conveyed a powerful sense of narrative momentum. His figures, while often idealized in the heroic mold typical of the era's adventure fiction, were rendered with anatomical accuracy and emotional weight.

His use of color, heavily influenced by Pyle's "broken color" technique, was a defining characteristic. Koerner employed a rich, often warm palette, applying paint in bold, visible strokes that gave his work texture and vibrancy. Sunlight seems to bake the plains in his daytime scenes, while campfires cast a dramatic glow in his nocturnal settings. This technique allowed him to capture the unique quality of light in the Western environment, from the harsh glare of midday to the soft hues of dawn and dusk.

Artistic Techniques and Influences Revisited

The "broken color" technique remained central to Koerner's style throughout his career. It allowed him to achieve a luminosity and energy that set his work apart. Unlike the more subtle blending of academic painting, Koerner's brushwork was often vigorous and apparent, contributing to the overall dynamism of the image. This approach, while rooted in Impressionist theory, was adapted for maximum narrative impact, ensuring that the illustrations were immediately engaging and readable, even when reproduced on the printed page.

Howard Pyle remained his primary artistic touchstone. Koerner revered his mentor, even writing a heartfelt eulogy for Pyle upon his death in 1911, published in the New Amsterdam Magazine. Pyle's emphasis on authenticity, emotional resonance, and storytelling through composition and light is evident in Koerner's mature work.

While Pyle was the dominant influence, Koerner operated within a broader artistic context. His Western themes inevitably invite comparison with artists like Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell, who were primarily known as easel painters documenting the West. However, Koerner's main focus was narrative illustration, shaping his work to complement specific texts. His style, while realistic, often carried a more romantic and dramatic charge aligned with the fiction he illustrated, compared to the sometimes more ethnographic or documentary approach of Remington or Russell. He was also a contemporary of other giants of illustration like J.C. Leyendecker, whose highly stylized, graphic approach offered a distinct contrast to Koerner's painterly realism, and Charles Dana Gibson, famous for his elegant social commentary.

Collaboration and Community: The Brandywine Legacy

Koerner's time with Howard Pyle fostered not only artistic growth but also lasting professional relationships. He remained connected to the network of artists often referred to as the Brandywine School, named after the region around Wilmington where Pyle's school was located. He shared studio space for a time with fellow Pyle students Otto Anton Fischer and William Henry Foster, benefiting from the camaraderie and mutual critique that such arrangements provided.

This community of artists, including N.C. Wyeth, Frank Schoonover, and Harvey Dunn, shared a common grounding in Pyle's methods and philosophy. While each developed a unique style, there was a shared emphasis on strong draftsmanship, dramatic composition, and narrative power. They often tackled similar themes, particularly adventure and historical subjects, and their collective output significantly shaped the visual culture of early 20th-century America. Koerner was an integral part of this influential circle.

Notable Works and Signature Pieces

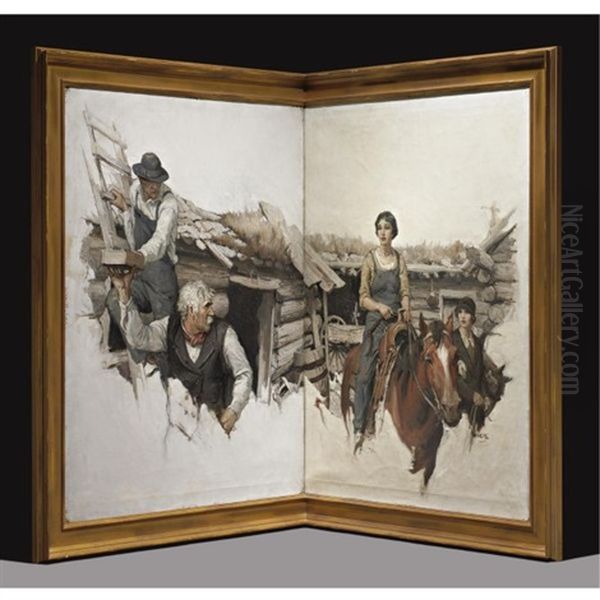

Several works stand out as particularly representative of Koerner's talent and thematic concerns. Madonna of the Prairie (1921), now housed in the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, is one of his most celebrated images. It depicts a pioneer woman and child inside a covered wagon, gazing out at the vast, uncertain landscape. The painting captures the hardship, resilience, and quiet dignity of westward expansion with poignant sensitivity, moving beyond simple adventure to touch on deeper human themes.

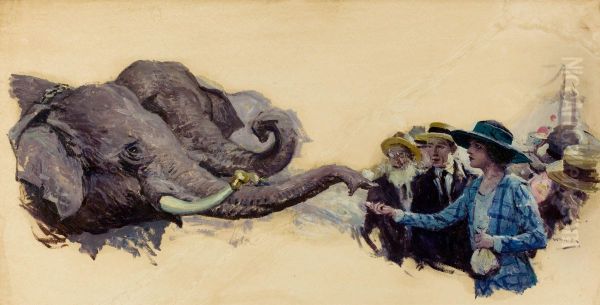

His illustrations for specific stories in The Saturday Evening Post became iconic visual representations of those narratives. Works like The Number One Boy (1922) or Putting on a Good Show (1927) exemplify his ability to distill a key moment of drama or character interaction into a single, compelling image. His illustrations for Emerson Hough's serialized novel The Covered Wagon (1922) were instrumental in visualizing this epic tale of the Oregon Trail for a mass audience. Other notable titles include Wild Geese, Feeding the Elephants (showcasing his versatility beyond Western themes), The Posse (1931), A Mystical Incantation (1922), and When Dynamite Found Gold (1921).

One painting gained particular notoriety long after Koerner's death: A Charge to Keep (1916). This image, depicting a group of horsemen charging up a hill, was acquired by George W. Bush and hung in the Oval Office during his presidency. It was also used as the title and cover image for his 1999 memoir. This brought Koerner's work renewed attention, though the painting's original context was unrelated to modern politics, sparking some discussion about the interpretation and use of historical art.

Later Years and Legacy

Koerner remained highly productive throughout the 1920s and into the early 1930s, his work consistently in demand. However, his health began to decline significantly after 1933. Despite facing physical challenges, he continued to work as his health permitted, driven by the passion that had fueled his entire career. He passed away in 1938 at his home in Interlaken, New Jersey, leaving behind a vast body of work that included thousands of illustrations and hundreds of paintings.

William Henry Dethlef Koerner's legacy is substantial. As a leading illustrator during the Golden Age, he played a crucial role in shaping the visual imagination of America. His depictions of the West, in particular, helped to codify the romantic and adventurous image of the frontier that dominated popular culture for decades. Alongside Howard Pyle, N.C. Wyeth, Maxfield Parrish, Jessie Willcox Smith, Elizabeth Shippen Green, and others, he demonstrated the power of illustration as both a commercial force and a legitimate form of artistic expression. His work successfully bridged the gap between fine art techniques and the demands of mass media, bringing painterly skill and dramatic storytelling to millions.

Exhibitions and Collections

Today, Koerner's original paintings and illustrations are highly sought after by collectors and institutions. The most significant public collection of his work resides at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming. This collection includes major paintings like Madonna of the Prairie and The Posse, acquired through museum purchases and, importantly, through a major gift from the artist's daughter, Ruth Koerner Oliver. Her donations ensured that a substantial part of her father's artistic legacy would be preserved and accessible to the public.

Koerner's works occasionally appear at auction, with houses like Bonhams handling sales of significant pieces, demonstrating their continued value in the art market. Beyond museum walls, his illustrations live on in the vintage magazines for which they were created, offering glimpses into the popular culture of their time. His contributions are also documented in studies of American illustration, such as books focusing on Howard Pyle and his school, and within archives dedicated to Western American art, like the Nan and Roy Farrington Jones Archive of Early California and Western Art. While large-scale solo exhibitions may be infrequent, his work is often included in group shows exploring the Golden Age of Illustration or the art of the American West.

Conclusion

William Henry Dethlef Koerner was more than just an illustrator; he was a visual storyteller who captured the spirit of an era and the enduring mythology of the American West. From his beginnings as a newspaper artist to his training under the legendary Howard Pyle and his subsequent rise to prominence in the nation's leading magazines, Koerner consistently delivered images filled with drama, emotion, and technical skill. His bold use of color, dynamic compositions, and empathetic portrayal of historical and fictional characters defined the look of Western adventure for generations. His work remains a testament to the power of illustration to shape perception and bring stories to vibrant life, securing his place as a master of the Golden Age and a key chronicler of the American experience.