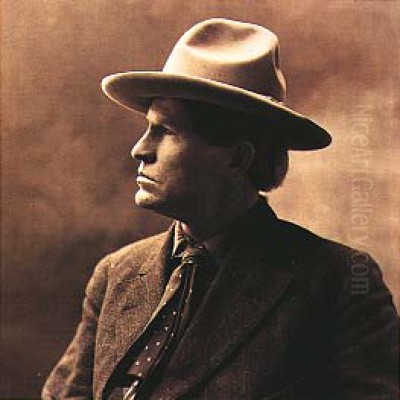

Charles Marion Russell stands as a monumental figure in American art, an artist whose life was as rugged and compelling as the Western landscapes and figures he immortalized on canvas and in bronze. Known affectionately as "the Cowboy Artist," Russell was more than just a painter; he was a chronicler, a storyteller, and a participant in the closing chapters of the American frontier. His work provides a unique window into the world of cowboys, Native Americans, and the wildlife of the Great Plains during a transformative period in American history. Unlike many artists who depicted the West from afar, Russell lived it, breathed it, and captured its essence with an authenticity born of direct experience. This article delves into the life, art, and enduring impact of Charles M. Russell, exploring his journey from a St. Louis youth fascinated by adventure to one of the most celebrated artists of the American West.

Early Life and the Call of the West

Charles Marion Russell was born on March 19, 1864, in St. Louis, Missouri, into a family with Scottish and Irish roots. His upbringing was comfortable, belonging to a family involved in the coal and fire brick industry. However, young Charlie was not destined for the family business. From an early age, he was captivated by tales of the American West, fueled by stories from relatives and the dime novels popular at the time. He spent hours sketching animals, Native Americans, and explorers, dreaming of adventure beyond the confines of city life.

His formal schooling was intermittent and largely unsuccessful; Russell's mind was clearly elsewhere. He preferred drawing and modeling small figures from wax or clay over traditional studies. His parents noted his artistic inclinations, and he even won a blue ribbon at a county fair for a small animal sculpture when he was just twelve. Despite their hopes for a more conventional path, Russell's yearning for the West proved irresistible. Recognizing his restless spirit and perhaps hoping the harsh realities might cure his romantic notions, his parents allowed him to travel to Montana in 1880, just after his sixteenth birthday.

This journey marked the true beginning of Russell's education. He arrived in the Judith Basin area of Montana, a vast territory still largely defined by open range, cattle ranching, and the fading presence of free-roaming Native American tribes. The romantic dream quickly met reality, but instead of being deterred, Russell embraced the challenges and immersed himself in the life he had longed for.

The Cowboy Years: Forging an Artist on the Range

Russell's initial foray into Montana involved working on a sheep ranch, an experience he reportedly disliked. He soon found his place among cattlemen, taking on the demanding role of a night herder or "night hawk," responsible for watching over the cattle herds during the long, dark hours. For over a decade, Russell lived the life of a working cowboy. This period was formative, providing him with an unparalleled, firsthand understanding of the rhythms, dangers, and camaraderie of ranch life.

He experienced the brutal winters, the dust of the trail drives, the skill required to handle horses and cattle, and the vast, often unforgiving beauty of the Montana landscape. He observed the interactions between cowboys, the behavior of wild animals, and the changing dynamics between settlers and the Native American populations whose lands were increasingly encroached upon. These experiences became the raw material for his art. He sketched constantly, often on any available surface – discarded paper, bunkhouse walls, or even the flaps of his chaps.

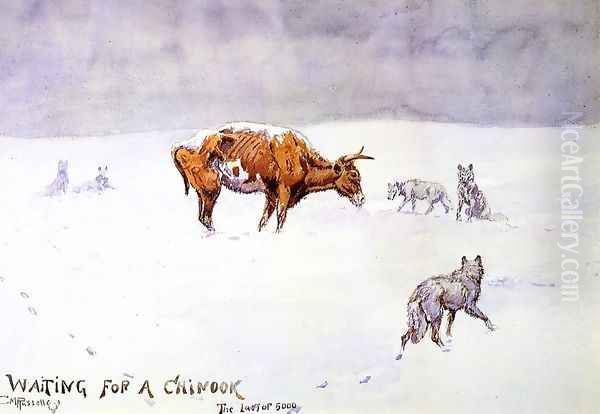

His fellow cowboys recognized his talent, often commissioning small drawings or watercolors. One famous anecdote involves the harsh winter of 1886-1887, which devastated cattle herds across the northern plains. When Russell's ranch foreman wrote to the owners asking how the herd had fared, Russell sketched a small watercolor depicting a starving cow, gaunt and surrounded by wolves under a bleak winter sky. Titled Waiting for a Chinook, this simple, poignant image conveyed the dire situation more powerfully than words ever could. It became one of his first widely recognized pieces, demonstrating his ability to capture the stark realities of Western life.

Embracing the Artist's Path

While Russell worked as a cowboy, art remained a passionate sideline. He was largely self-taught, honing his skills through constant observation and practice. His early works were often rough but possessed a vitality and accuracy that set them apart. He wasn't just imagining the West; he was documenting the life he knew intimately. His depictions of horses in motion, the specific gear used by cowboys, and the subtle details of animal anatomy were remarkably precise.

A turning point came in 1888 when he spent the winter living with the Blood Indians, part of the Blackfoot Confederacy, in Alberta, Canada. This experience profoundly impacted him, fostering a deep respect and empathy for Native American culture and traditions at a time when they were often misunderstood or vilified. He learned about their customs, beliefs, and struggles, and this understanding would inform his portrayals of Native Americans throughout his career, often depicting them with dignity and a sense of their connection to the land.

By the early 1890s, Russell's reputation as an artist was growing locally. He began receiving more commissions and selling his work. In 1896, he made two decisions that would fundamentally shape his future: he married Nancy Cooper and decided to pursue art as a full-time profession. The couple settled in Great Falls, Montana, which would remain their home base. Giving up the cowboy life allowed Russell to dedicate himself entirely to his art, moving from occasional sketches to more ambitious oil paintings and sculptures.

Nancy Cooper Russell: The Driving Force

The marriage to Nancy Cooper was pivotal not just personally but professionally. While Charlie Russell possessed immense talent and firsthand knowledge, he lacked business acumen and was known for his easygoing nature, sometimes giving away sketches or selling works for modest sums. Nancy, seventeen years his junior, was intelligent, ambitious, and possessed a keen understanding of how to manage and promote her husband's career.

Nancy took charge of the business side of Russell's art. She organized his studio, managed his finances, negotiated prices, and cultivated relationships with dealers and collectors. She recognized the true value of his work and insisted on prices commensurate with his growing reputation. Nancy was instrumental in arranging exhibitions, first locally, then regionally, and eventually in major art centers like New York, Chicago, and even London.

She carefully curated his image as the authentic "Cowboy Artist," understanding the appeal of his background to an Eastern audience increasingly fascinated by the romantic myth of the West. Nancy's tireless efforts transformed Russell from a talented regional artist into an internationally recognized figure. Without her drive and business savvy, it is unlikely that Charles M. Russell would have achieved the level of fame and financial success he enjoyed during his lifetime. She ensured his legacy was built on a solid foundation, allowing him to focus on creating.

Life Among the Native Peoples

Russell's time spent living with the Blood Indians in 1888 was not an isolated incident but part of a broader pattern of engagement and respect for Native American cultures. Throughout his years in Montana, he sought out interactions with various tribes, including the Blackfeet, Crow, Kootenai, and Flathead peoples. He learned basic sign language, listened to their stories, and observed their way of life with genuine interest and admiration.

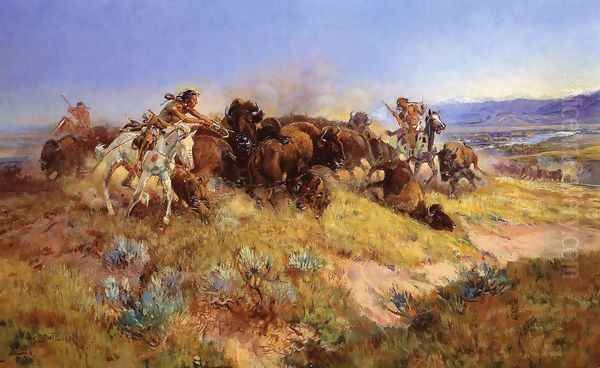

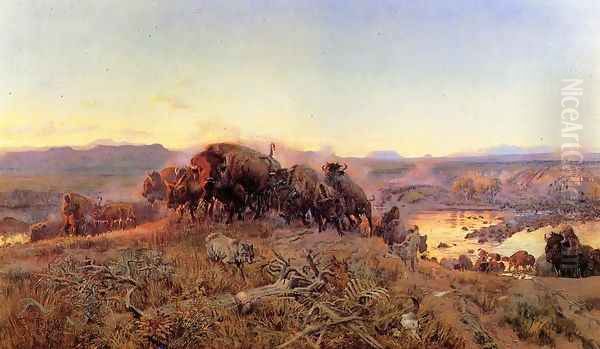

This empathy is evident in his artwork. Unlike many contemporaries who depicted Native Americans primarily as savage adversaries or romanticized stereotypes, Russell often portrayed them with dignity, focusing on their daily lives, spiritual practices, and resilience in the face of immense change. Works like The Medicine Man or paintings depicting buffalo hunts before the herds were decimated show a deep understanding of their culture and a sense of loss for a vanishing way of life.

He was critical of the impact of westward expansion on Native populations and the destruction of the buffalo herds, themes that subtly permeate many of his works. He saw the end of an era not just for the cowboy but for the original inhabitants of the plains. His ability to portray the Native American perspective, informed by his personal relationships and observations, adds a significant layer of depth and historical value to his artistic contributions. He captured a world that was rapidly disappearing, preserving aspects of its culture through his art.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Charles M. Russell's artistic style is characterized by its narrative power, dynamic energy, and meticulous attention to detail, all grounded in his firsthand experience. While largely self-taught, he developed a sophisticated command of composition, color, and form. His work is often categorized within the broader movement of American Romanticism, particularly in its celebration of nature, individualism, and dramatic action, but it is tempered by a strong undercurrent of realism born from his life on the range.

His paintings burst with movement – thundering buffalo herds, cowboys breaking bucking broncos, intense moments during Native American hunts or battles. He had an exceptional ability to capture the anatomy and motion of horses and wild animals, skills honed through years of direct observation. His use of color was vibrant and expressive, effectively conveying the changing light of the Montana skies, the dust of the plains, or the richness of Native American attire.

Russell worked proficiently in multiple mediums. His oil paintings are perhaps his most famous works, known for their complex compositions and narrative depth. He was also a master of watercolor, often using it for quicker, more spontaneous sketches or studies, yet achieving remarkable detail and luminosity. Furthermore, Russell was a talented sculptor, creating bronze statues that captured the three-dimensional energy of his subjects, from cowboys and wildlife to poignant Native American figures. His bronze work, like Smoking Up or Cowboy and Bear, displays the same dynamism and anatomical accuracy found in his paintings.

Themes and Subjects: Chronicling the West

The subject matter of Russell's art revolved entirely around the American West he knew and loved. He created an estimated 4,000 works of art throughout his career, exploring a range of themes that collectively paint a comprehensive picture of the era. Cowboys were a central focus, depicted not just in moments of high action like roundups or rodeos (A Bronc Twister), but also in quieter scenes of camp life or solitary rides across the vast landscape, capturing the camaraderie and isolation of their existence.

Native Americans were another major theme, treated with sensitivity and respect. Russell depicted their hunts (Buffalo Hunt), ceremonies (The Medicine Man), interactions with traders and explorers (Lewis and Clark Meeting the Flathead Indians), and the profound changes impacting their traditional ways. His portrayals often carried an elegiac tone, mourning the loss of their freedom and connection to the land.

Wildlife was integral to Russell's West. He painted buffalo, elk, deer, bears, and wolves with anatomical precision, often showing them as powerful symbols of the untamed wilderness. The Montana landscape itself was a recurring subject, with its dramatic mountains, sweeping plains, and distinctive Big Sky light serving as the backdrop for his narratives. He also documented specific historical events, such as the Lewis and Clark Expedition's journey through Montana, commissioned for the Montana State Capitol building. Through these diverse themes, Russell chronicled the complex tapestry of life on the northern plains during a period of profound transition.

Masterworks and Notable Pieces

Among Russell's vast body of work, several pieces stand out as particularly iconic or representative of his talent and themes. Waiting for a Chinook (1887), the small watercolor sketch of the starving cow, remains significant for its early demonstration of his narrative power and its role in bringing him initial recognition. It captured the harsh reality behind the romantic image of the cowboy.

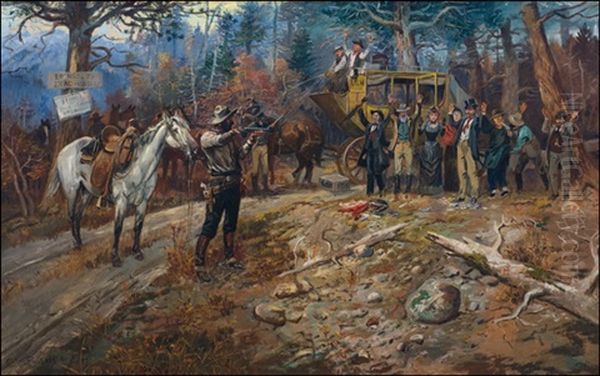

Piegans (1902), depicting members of the Piegan Blackfeet tribe preparing to move camp, showcases his detailed observation of Native American life and his skill in rendering complex group scenes. This painting achieved a remarkable .6 million at auction in 2005, highlighting the high regard and market value of his major works. Another high-value piece, The Hold Up (1899), captures the drama and danger of the Old West with characteristic energy.

When the Land Belonged to God is a powerful depiction of a vast buffalo herd moving across the plains before widespread settlement, evoking a sense of primordial wilderness and loss. His mural for the Montana House of Representatives, Lewis and Clark Meeting the Flathead Indians at Ross' Hole, is a major historical work demonstrating his ability to handle large-scale, complex compositions. In sculpture, pieces like Smoking Up, showing a cowboy firing his pistols exuberantly, or the detailed studies of wildlife, exemplify his mastery of bronze. These works, among many others, solidify Russell's reputation as a master storyteller of the American West.

Russell and His Contemporaries

Charles M. Russell occupied a unique space in the landscape of American art. While he worked outside the mainstream art movements centered in the East Coast cities, his fame grew to national and international levels. His most direct contemporary and sometimes perceived rival in the field of Western art was Frederic Remington (1861-1909). Both artists depicted similar subjects – cowboys, soldiers, Native Americans, and Western landscapes. However, Remington, who was formally trained and worked extensively as an illustrator for Eastern publications, often presented a more dramatic, sometimes more conflict-oriented view of the West, while Russell's work, born from decades of lived experience, often possessed a greater sense of intimacy and nuanced understanding, particularly regarding cowboy life and Native cultures.

Beyond Remington, Russell's work can be contextualized alongside other artists interested in the West. The Taos Society of Artists, founded in 1915, included painters like Joseph Henry Sharp, E. Irving Couse, Oscar E. Berninghaus, W. Herbert Dunton, Ernest L. Blumenschein, and Bert Geer Phillips, who were drawn to the landscapes and Native cultures of New Mexico. While their focus was the Southwest, they shared Russell's interest in preserving a vision of the West. Other notable Western artists included Olaf C. Seltzer, a friend and fellow Montana artist whose style sometimes mirrored Russell's, and Maynard Dixon, known for his modernist depictions of Western landscapes and peoples.

Russell's narrative and illustrative talents also connect him to the great American illustrators of the era, such as Howard Pyle and N.C. Wyeth, who often tackled historical and adventure themes, including Western subjects, shaping popular perceptions of American history. Comparing Russell to artists focused on other aspects of American life, like the realist Winslow Homer with his scenes of nature and rural life, or later, the Ashcan School artists like Robert Henri documenting urban realities, highlights Russell's specific dedication to capturing the vanishing frontier.

The Storyteller: Russell's Writing and Humor

Charles Russell was not only a visual artist but also a natural storyteller in words. He wrote numerous short stories and articles, often illustrated with his own sketches, capturing the folklore, humor, and everyday experiences of the West. His writing, like his art, was characterized by its authenticity, wit, and unpretentious style. He published collections like Rawhide Rawlins Stories (1921) and Trails Plowed Under (1927), which preserved cowboy yarns and anecdotes in the vernacular language of the range.

His personal letters were often works of art in themselves, filled with humorous observations and embellished with small watercolor sketches or ink drawings. He famously signed many letters with a drawing of a buffalo skull, sometimes depicted in comical situations reflecting the letter's content. This wit and warmth were part of his personality. Friends and acquaintances described him as a captivating raconteur, able to hold listeners spellbound with tales of his cowboy days or Native American legends. His famous quote, "I believe in luck and have had lots of it," reflects his humble and humorous outlook on life. This storytelling ability, whether through paint, bronze, or words, was central to his appeal and his effectiveness in communicating the spirit of the West.

Later Years and Recognition

As Russell's fame grew, thanks in large part to Nancy's management, his life changed. He traveled more frequently, exhibiting his work in major cities and spending winters in California later in life. His studio in Great Falls became a landmark, and he welcomed visitors from all walks of life, from working cowboys to celebrities and politicians. He received major commissions, including the Montana Capitol mural, and his works commanded increasingly high prices. Collectors included prominent figures like oil tycoon E. L. Doheny and humorist Will Rogers, who became a close friend.

Despite his success, Russell remained deeply connected to Montana and the Western life he depicted. He continued to produce a prolific amount of work, always striving for accuracy and emotional resonance. He became an advocate for conservation, lamenting the changes he saw overtaking the landscapes and wildlife he loved. His status as a cultural icon grew, particularly in Montana, where he was revered.

Charles M. Russell died of heart failure on October 24, 1926, at his home in Great Falls, at the age of 62. His death was mourned throughout Montana and across the nation. On the day of his funeral, the schools in Great Falls closed to honor him, a testament to his stature as a local hero and a beloved figure. His legacy was already firmly established, but his influence would continue to grow posthumously.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Charles Marion Russell's legacy is multifaceted and enduring. He is widely regarded as one of the most important artists of the American West, whose work captured a pivotal moment in history with unparalleled authenticity and artistic skill. His deep knowledge, gained through years of living the life he painted, sets him apart from many other Western artists. His ability to convey narrative, emotion, and specific detail continues to captivate audiences.

His work played a significant role in shaping the popular image and mythology of the American West. While some critics argue that his depictions occasionally leaned towards romanticization or nostalgia, particularly in his later years, his overall body of work provides invaluable documentation of cowboy culture, Native American life, and the Western environment. His sympathetic portrayal of Native Americans, in particular, offers an important counter-narrative to more prejudiced views common in his time.

Today, Russell's paintings and sculptures are highly sought after by collectors and are prominently featured in major museums across the United States, including the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls, Montana; the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas; the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming; and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. He was inducted into the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame and received numerous posthumous honors. His influence extends beyond the art world, inspiring writers, filmmakers, and musicians, and contributing to the ongoing fascination with the American West. He remains a beloved figure, the quintessential "Cowboy Artist" whose life and work embody the spirit of the frontier.

Conclusion: The Enduring Vision of the Cowboy Artist

Charles Marion Russell's journey from a St. Louis boy dreaming of adventure to the preeminent artist of the American West is a remarkable story. He was an artist uniquely positioned by time and experience to chronicle the twilight of the open range era. His paintings, sculptures, and stories offer more than just depictions of cowboys and Indians; they are imbued with the authenticity of lived experience, a deep respect for his subjects, and a profound sense of place. Russell captured the action, the beauty, the hardship, and the spirit of the West with a skill and empathy that continue to resonate. Through his vast and vibrant body of work, Charles M. Russell ensured that the world he knew – the world of the working cowboy, the free-roaming Native American tribes, and the untamed wilderness of Montana – would not be forgotten, securing his place as a true icon of American art and culture.