William Herbert Dunton, often known affectionately as "Buck," stands as a significant figure in the annals of American art. Born in Augusta, Maine, in 1878, and passing away in the vibrant art colony of Taos, New Mexico, in 1936, Dunton dedicated his artistic life to capturing the essence of the American West. His work serves as both a celebration and a poignant record of a world that was rapidly transforming during his lifetime. He was both a highly successful illustrator and a dedicated easel painter, recognized particularly for his depictions of cowboys, wildlife, and the sprawling, untamed landscapes of the West.

Dunton's journey into art began early, fueled by an innate passion for drawing and the outdoors. Growing up in New England, he developed a keen interest in nature and hunting, subjects that would later dominate his artistic output. By the age of sixteen, his talent was already evident; he sold his first drawing, marking the beginning of a lifelong commitment to the arts. This early success spurred him to seek formal training to hone his skills.

He pursued his artistic education first at the Cowles Art School in Boston, a notable institution that provided foundational training to many aspiring artists. Seeking further refinement and exposure to the bustling art scene, Dunton later moved to New York City. There, he enrolled in the prestigious Art Students League, a vital hub for American artists, where he could immerse himself in rigorous study and interact with fellow creatives. This period of formal training equipped him with the technical proficiency that would underpin his future success.

The Illustrator's Craft

Before dedicating himself fully to easel painting, Dunton forged a highly successful career as a commercial illustrator. In the early 20th century, illustrated magazines were a primary source of visual information and entertainment, and skilled illustrators were in high demand. Dunton quickly made a name for himself, contributing striking images to some of the nation's leading publications, including Harper's Weekly, Collier's, Scribner's Magazine, and Field and Stream.

His illustrations were lauded for their accuracy, dynamism, and narrative clarity. Whether depicting a tense moment in a Western story or capturing the anatomy of wildlife for an outdoor magazine, Dunton brought a level of realism and detail that captivated readers. This commercial work not only provided him with a steady income but also sharpened his observational skills and his ability to compose compelling scenes. The discipline required for illustration—meeting deadlines, adhering to narrative requirements, and ensuring anatomical and historical accuracy—proved invaluable when he later transitioned more fully to painting.

The Lure of the West

Despite his success in the East, Dunton felt an irresistible pull towards the American West. This fascination wasn't merely academic; it was deeply personal, nurtured by annual summer trips he began taking as a young man. He ventured into Montana, Wyoming, Oregon, and eventually New Mexico and Old Mexico, seeking authentic experiences far removed from the urban centers of the East Coast.

During these expeditions, Dunton deliberately immersed himself in the Western way of life. He lived and worked alongside cowboys, rode with seasoned hunters, and spent time with trappers, learning the rhythms and realities of life on the range and in the wilderness. These were not tourist excursions; they were formative experiences that provided him with firsthand knowledge of his subjects—the way a cowboy sat a horse, the specific gear used by hunters, the subtle colors of the desert landscape, and the behavior of wild animals. This deep, experiential understanding infused his later artwork with an undeniable authenticity.

Taos: A New Beginning

The year 1912 marked a pivotal turning point in Dunton's life and career. While in New York, he encountered fellow artist Ernest Blumenschein, who had already discovered the artistic potential of Taos, New Mexico. Blumenschein, recognizing Dunton's passion for Western subjects, strongly advised him to visit the small, high-desert town. He suggested that Taos, with its unique blend of Native American and Hispanic cultures, stunning landscapes, and brilliant light, offered precisely the kind of subject matter Dunton was seeking.

Heeding Blumenschein's advice, Dunton made his first trip to Taos that same year. He was immediately captivated. The rugged mountains, the vast plains, the distinctive adobe architecture, and the vibrant cultural life of the region resonated deeply with his artistic sensibilities. He found the subjects he yearned to paint—cowboys, Native Americans, dramatic landscapes, and abundant wildlife—all within reach. He also sought further instruction, briefly studying painting techniques with the Russian-born Taos artist Leon Gaspard, known for his vibrant colors and impressionistic style.

The experience was transformative. Dunton realized that to truly capture the spirit of the West he loved, he needed to live there. He began spending more time in Taos, eventually deciding to relocate permanently. This move signified a shift in his focus, away from the demands of commercial illustration and towards a deeper engagement with fine art painting, dedicated to preserving the West he knew.

The Taos Society of Artists

Dunton's arrival in Taos coincided with a burgeoning artistic movement. He quickly connected with other artists who had been drawn to the region's unique allure, including Ernest Blumenschein, Bert Geer Phillips, Joseph Henry Sharp, Eanger Irving Couse, and Oscar E. Berninghaus. These artists shared a common goal: to depict the landscapes and cultures of the Southwest authentically and to promote their work to a national audience.

In 1915, Dunton became one of the founding members of the Taos Society of Artists (TSA). This organization would become one of the most influential art colonies in America. The TSA organized traveling exhibitions, sending paintings by its members to galleries and museums across the country. This collective effort brought national recognition to Taos and established its reputation as a major center for American art, particularly art focused on Western and Native American themes.

Dunton played an active role in the Society during its formative years. The TSA provided a supportive community and a platform for exhibition, though it was not without its internal dynamics. The members, all strong artistic personalities, sometimes had differing views on art and the direction of the Society. Dunton himself, known for his independent spirit, reportedly resigned from the TSA in 1922 due to personal or artistic conflicts, preferring thereafter to manage his own exhibitions and career path. Despite this, his association with the founding of the TSA remains a crucial part of his legacy.

Dunton's Artistic Vision: Realism and Preservation

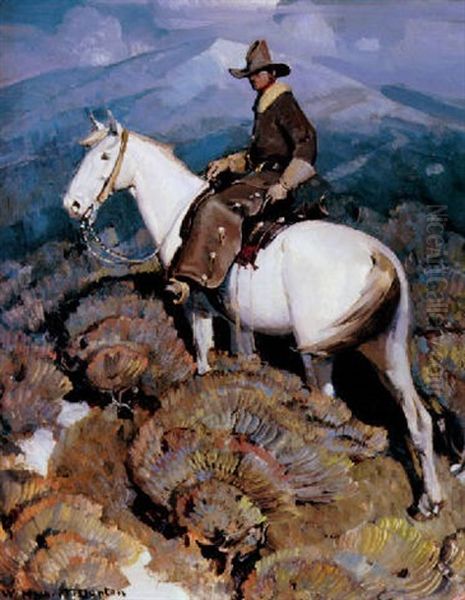

As Dunton settled into his life as a Taos painter, his artistic style matured. He remained committed to realism, believing in the importance of accurate representation. His background as an illustrator had instilled in him a meticulous attention to detail. This is evident in the precise rendering of clothing, saddles, firearms, and the powerful musculature of horses and wild animals that characterize his paintings. He possessed an almost scientific interest in anatomy and authenticity.

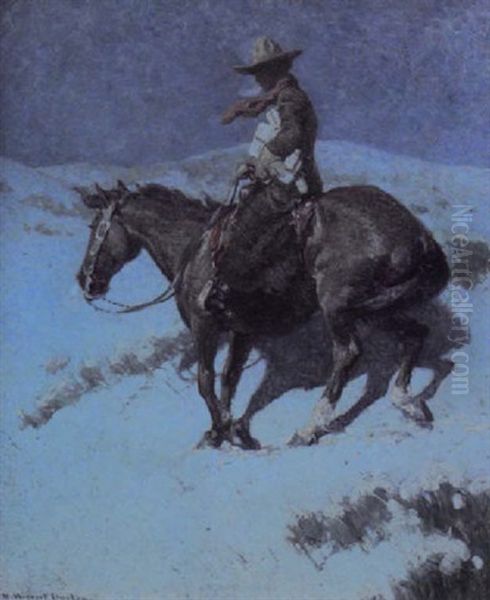

However, Dunton's work transcended mere technical accuracy. He infused his paintings with a sense of drama and atmosphere, often using strong compositions and dynamic light effects. He aimed to capture not just the appearance of the West, but its spirit—the rugged independence of the cowboy, the majesty of the landscape, the inherent dignity of wildlife. He saw himself as a chronicler, documenting a way of life and a pristine wilderness that he keenly felt were disappearing under the pressures of modernization.

His dedication to preservation became a defining aspect of his artistic mission. He lamented the fencing of the open range, the decline of large game populations, and the erosion of traditional cowboy culture. Through his art, he sought to create a lasting record of this "Old West" before it vanished completely. This preservationist impulse gives his work a particular poignancy and historical significance.

Themes of the Untamed West

Dunton's body of work revolves around several key themes, all drawn from his deep connection to the American West.

The Cowboy: Perhaps Dunton's most iconic subject is the American cowboy. He depicted cowboys not just as romantic figures, but as working men, showing them riding, roping, and navigating the challenges of the range. He captured their characteristic attire and equipment with precision, but also conveyed their resilience and connection to the landscape. Works like The Horse Rustler exemplify his ability to create powerful, archetypal images of the Western horseman.

Wildlife: A passionate outdoorsman and hunter himself, Dunton had profound respect and admiration for Western wildlife. He painted grizzly bears, deer, antelope, and mountain lions with anatomical accuracy and a sense of their inherent wildness. He often depicted animals within their natural habitats, emphasizing their integration with the landscape. His goal was to portray their "strength and grace," capturing their vitality before populations dwindled further.

Landscapes: The dramatic landscapes of New Mexico and the broader West were a constant source of inspiration for Dunton. He painted the towering mountains, the expansive plains dotted with sagebrush, and the unique quality of light found in the high desert. His landscapes often serve as powerful backdrops for his figures and animals, but they also stand alone as testaments to the beauty and grandeur of the Western environment.

Native American Life: While perhaps less central to his oeuvre than cowboys or wildlife compared to some other Taos artists like Couse or Sharp, Dunton did depict Native American subjects. He approached these themes with the same commitment to authenticity, striving for respectful and accurate portrayals of individuals and their cultural context within the Taos region.

Masterworks and Signature Pieces

Several paintings stand out as representative of William Herbert Dunton's artistic achievement.

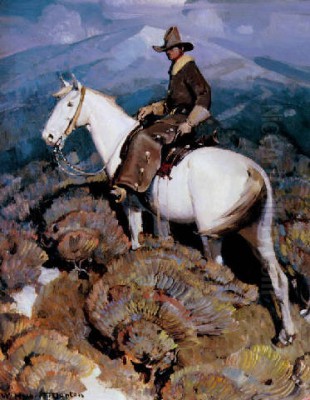

The Horse Rustler: Often considered one of his masterpieces, this painting depicts a lone cowboy on a white horse against a dramatic mountain backdrop. The composition is strong, the figure iconic, embodying the solitude and self-reliance associated with the Western mythos, rendered with Dunton's characteristic realism.

The Custer Fight: This work offers a unique perspective on the Battle of Little Bighorn. Rather than focusing on Custer and his soldiers, Dunton chose to depict the intensity of the battle from the viewpoint of the victorious Sioux warriors, showcasing his interest in diverse perspectives within Western history.

Glorieta: This painting garnered significant attention when it sold at auction for a high price, highlighting the increasing market recognition of Dunton's work. It likely depicts a scene characteristic of the Glorieta Pass area near Santa Fe, showcasing his skill in rendering the specific light and landscape of New Mexico.

Delivering the Mail, A Day in the Life of a Lazy Cowhand, and End of the Day: These titles suggest Dunton's interest in capturing the everyday moments and narratives of Western life, moving beyond purely heroic depictions to show the routines and realities of the cowboy experience.

These works, among many others, demonstrate Dunton's skill in composition, his mastery of anatomical detail, and his commitment to portraying the West with both accuracy and evocative power.

Beyond the Canvas: Lithography and Murals

Dunton's artistic output was not limited to oil painting. In his later years, he explored the medium of lithography. This printmaking technique allowed him to reproduce his Western scenes and reach a wider audience. His lithographs often revisited his favorite themes—cowboys, wildlife, and dramatic landscapes—rendered in the distinct black-and-white tonalities of the medium.

He also participated in the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) during the Great Depression. The PWAP was a New Deal program designed to employ artists by commissioning them to create public art. Dunton contributed murals, likely depicting scenes of Western life and history, further demonstrating his commitment to making his vision of the West accessible and preserving its legacy through public art initiatives. These activities underscore his enduring focus on Western themes across different artistic forms.

Influences, Contemporaries, and Context

William Herbert Dunton operated within a rich artistic context, drawing inspiration from predecessors while working alongside notable contemporaries. His work is often discussed in relation to Frederic Remington, arguably the most famous Western artist of the preceding generation. Like Remington, Dunton was skilled in both illustration and painting, and shared an interest in cowboys and dramatic Western action. However, Dunton developed his own distinct style, often characterized by brighter palettes and perhaps a greater emphasis on the harmony between figures and the landscape.

Within Taos, his closest colleagues were the other founding members of the TSA: Ernest Blumenschein, Eanger Irving Couse, Joseph Henry Sharp, Bert Geer Phillips, and Oscar E. Berninghaus. Each had their own specialty—Blumenschein's powerful landscapes and Native American scenes, Couse's fire-lit portrayals of Taos Pueblo natives, Sharp's ethnographic portraits, Phillips' romantic depictions, and Berninghaus's scenes of local life. Later members like Walter Ufer, Victor Higgins, and Kenneth Adams further diversified the Society's output. Dunton's unique contribution was his intense focus on the cowboy and wildlife, and his explicit mission to document the "vanishing" aspects of the West.

Beyond the TSA, other major figures in Western American art during Dunton's era included Charles M. Russell, the beloved "cowboy artist" of Montana known for his narrative paintings and sculptures; Maynard Dixon, whose stylized depictions captured the vastness and light of the Western landscape; Frank Tenney Johnson, famed for his atmospheric nocturnes of the West; and W. R. Leigh, another artist known for his detailed portrayals of Western scenes and wildlife. While Dunton shared subject matter with these artists, his meticulous realism combined with his Taos affiliation gave his work a unique place within the broader genre of Western American art.

Later Years and Health Challenges

Dunton's later life was marked by health problems that ultimately impacted his ability to work. In 1928, a significant incident occurred when he was kicked by a horse. This injury led to complications, including the development of ulcers, which plagued his health thereafter. His physical condition gradually deteriorated over the following years.

Despite his declining health, Dunton continued to paint and pursue his artistic interests, including lithography. However, the physical demands of painting, especially potentially large canvases or fieldwork, likely became increasingly difficult. In 1935, he received a devastating diagnosis of prostate cancer. William Herbert "Buck" Dunton passed away in Taos in 1936, at the age of 57, leaving behind a significant body of work dedicated to the American West he so deeply loved.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

William Herbert Dunton occupies an important position in American art history, particularly within the Western genre and the Taos art colony. As a founding member of the Taos Society of Artists, he contributed significantly to establishing Taos as a major art center and bringing the landscapes and cultures of the Southwest to national attention. His dual career as a successful illustrator and a dedicated painter demonstrates his versatility and technical skill.

His most enduring legacy lies in his commitment to documenting the American West, especially the figure of the cowboy and the region's wildlife, with authenticity and artistic integrity. He captured a specific moment in history, portraying a world that was undergoing profound change. His work serves as a valuable historical record, imbued with his personal passion and preservationist concerns.

For many years, Dunton's work, like that of some other Western artists focused on realism, was perhaps somewhat undervalued within broader art historical narratives that prioritized modernism. However, in recent decades, there has been a resurgence of interest in Western American art and the artists of the Taos colony. Dunton's paintings are increasingly sought after by collectors and museums, and his auction prices have risen significantly, reflecting a growing appreciation for his technical skill, his unique vision, and his contribution to American cultural heritage. He is remembered as a master draftsman, a keen observer, and a heartfelt chronicler of the vanishing frontier.

Conclusion

William Herbert "Buck" Dunton's life was a testament to his unwavering passion for the American West. From his early days as a successful illustrator in the East to his pivotal role in the Taos art colony, he dedicated his considerable talents to capturing the essence of a world defined by rugged landscapes, independent spirits, and magnificent wildlife. His meticulous realism, combined with a dramatic flair and a deep sense of historical purpose, resulted in a body of work that continues to resonate. As both an artist and a chronicler, Dunton secured his place as a key interpreter of the Western experience, leaving behind a powerful visual legacy of the land and life he knew and loved.