An Enduring Figure in American Art

Newell Convers Wyeth, universally known as N.C. Wyeth, stands as a titan in the realm of American illustration and painting. Born on October 22, 1882, in Needham, Massachusetts, and tragically passing on October 19, 1945, near his home in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, Wyeth forged a career that not only defined the visual landscape of classic literature for generations but also captured the essence of American history, adventure, and pastoral life. His prolific output, numbering over 3,000 paintings and illustrations for 112 books, cemented his place as a cornerstone of the Golden Age of American Illustration and the patriarch of a remarkable artistic dynasty. His work resonates with a dramatic intensity and narrative clarity that continues to captivate audiences today.

Wyeth's art is deeply rooted in the American experience. From the rugged landscapes of the West to the intimate settings of his Brandywine Valley home, his canvases pulse with energy, emotion, and a profound connection to his subjects. He was more than an illustrator; he was a visual storyteller whose imagination gave definitive form to pirates, knights, pioneers, and heroes, shaping the popular iconography of American adventure and mythos. His legacy extends beyond his own canvases, living on through the Brandywine School tradition he inherited and the artistic lineage he fostered.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

N.C. Wyeth's formative years were spent on a farm in Needham, Massachusetts. This rural upbringing instilled in him a deep appreciation for nature and the rhythms of outdoor life, themes that would echo throughout his artistic career. His family background presented a dichotomy of influences: his mother, Henriette Zirgeli Wyeth, descended from Swiss immigrants, recognized and nurtured his burgeoning artistic talent. Conversely, his father, Andrew Newell Wyeth, held more pragmatic views, initially encouraging his son towards a more practical application of his drawing skills, such as drafting.

This paternal advice led Wyeth initially to study drafting at the Mechanics Arts High School in Boston. However, his innate passion for fine art soon guided him to the Massachusetts Normal Art School (now the Massachusetts College of Art and Design). It was here, under the mentorship of instructor Richard Andrew, that Wyeth found crucial encouragement. Andrew recognized the young artist's potential and steered him towards the burgeoning field of illustration, a path that perfectly suited Wyeth's narrative inclinations and technical skills. This guidance proved pivotal, setting Wyeth on the course that would lead him to national prominence.

The Pivotal Influence of Howard Pyle

A defining moment in N.C. Wyeth's artistic development came in 1902 when he enrolled in Howard Pyle's prestigious School of Art in Wilmington, Delaware. Pyle, often hailed as the "Father of American Illustration," was a charismatic teacher whose influence shaped a generation of artists. His school, operating first in Wilmington and later in nearby Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, was renowned for its rigorous training and unique pedagogical approach. Pyle emphasized the importance of historical accuracy, dramatic composition, and, crucially, immersing oneself in the subject matter – urging his students to "live" the stories they depicted.

Wyeth absorbed Pyle's teachings wholeheartedly, becoming one of his most dedicated and successful pupils. He studied under Pyle until 1904, internalizing the master's emphasis on vivid storytelling, dynamic action, and emotional resonance. Pyle's Brandywine School fostered a distinct style characterized by rich palettes, strong lighting, and a romantic yet robust realism. Wyeth thrived in this environment, honing his technical skills and developing the powerful narrative style that would become his hallmark. He joined a cohort of talented Pyle students, including artists like Frank Schoonover and Harvey Dunn, who also went on to achieve significant success in illustration.

Launching an Illustrious Career

Wyeth's talent, coupled with the exceptional training under Howard Pyle, quickly led to professional success. His career launched meteorically when, still a student, he secured his first major commission. The prestigious Saturday Evening Post featured a Wyeth illustration of a bucking bronco on its cover on February 21, 1903. This debut marked the beginning of a long and fruitful relationship with major periodicals. Publishers recognized the power and appeal of his work, and commissions flowed readily from magazines such as Scribner's, Harper's Monthly, and McClure's.

This period coincided with the "Golden Age of American Illustration" (roughly 1880s-1920s), a time when advancements in printing technology allowed for high-quality reproduction of artwork, and illustrated magazines and books enjoyed immense popularity. Wyeth emerged as a leading figure in this vibrant field, alongside contemporaries like Maxfield Parrish, known for his luminous fantasy worlds, and fellow Pyle student Jessie Willcox Smith, celebrated for her sensitive portrayals of children. Wyeth's ability to capture action, drama, and historical atmosphere made his work highly sought after for adventure stories and historical narratives.

Masterworks of Illustration: Scribner's Classics

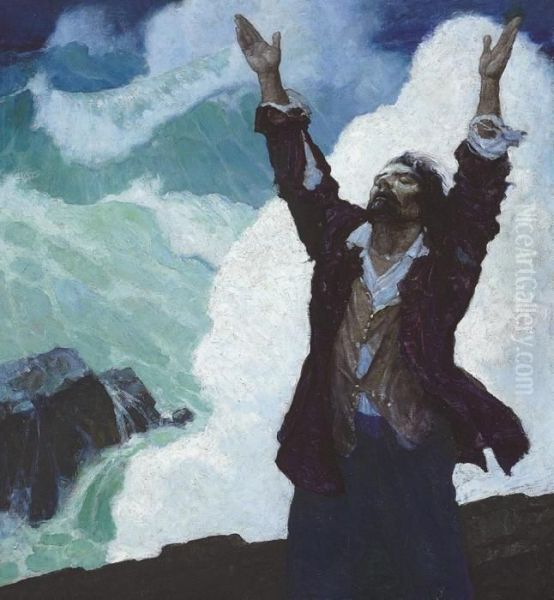

Wyeth's most enduring legacy arguably lies in his illustrations for the Scribner's Illustrated Classics series. Beginning in 1911 with Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island, Wyeth created a body of work that redefined these literary staples for the visual age. His seventeen paintings for Treasure Island were revolutionary; their dynamic compositions, rich colors, and dramatic intensity brought Long John Silver, Jim Hawkins, and the Hispaniola to life with unprecedented vividness. Images like the blind Pew tapping his way towards the Admiral Benbow inn, or the pirates confronting Jim on the stockade, became iconic, inseparable from the text itself.

The success of Treasure Island led to further commissions from Scribner's. Wyeth went on to illustrate classics such as Kidnapped (1913), The Black Arrow (1916), The Boy's King Arthur (1917), The Mysterious Island (1918), The Last of the Mohicans (1919), Robinson Crusoe (1920), and Robin Hood (1921). Each volume featured Wyeth's immersive and powerful paintings, which did more than merely decorate the text; they amplified the stories' emotional impact and historical atmosphere, shaping the visual imagination of countless young readers and setting a new standard for book illustration.

Capturing the American West

Inspired by his mentor Howard Pyle's dictum to experience subjects firsthand, Wyeth undertook several formative trips to the American West early in his career. In 1904 and 1906, he traveled to Colorado and the Navajo Nation territory, immersing himself in the landscapes, cultures, and lifestyles of the region. He worked as a cowboy, participated in roundups, carried mail through remote areas (a job taken partly out of financial necessity during one trip), and spent time observing and sketching Native American life. These experiences provided him with invaluable authentic detail and a deep feeling for the Western spirit.

This firsthand knowledge infused his Western illustrations with a vitality and accuracy that set them apart. Unlike artists who relied solely on imagination or secondary sources, Wyeth could depict the specific quality of light on the plains, the dynamic movement of horses, and the rugged character of cowboys and Native Americans with convincing authority. His Western work, while sharing thematic territory with renowned Western artists like Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell, possessed Wyeth's unique dramatic flair and compositional energy. These trips profoundly impacted his art, providing a wellspring of inspiration for numerous magazine illustrations and paintings.

Evolution of Artistic Style

While best known for his illustrations, N.C. Wyeth considered himself primarily a painter and continually evolved his style throughout his career. His early work clearly shows the influence of Howard Pyle, characterized by strong narrative content, meticulous detail, and dramatic realism. He possessed an exceptional ability to stage a scene, using bold compositions, often with figures seen from dynamic angles, and a masterful command of light and shadow to heighten emotional impact. His color palette was typically rich and resonant, capable of conveying mood ranging from bright adventure to somber tension.

Over time, particularly in his easel paintings and later illustrations, Wyeth's style loosened. While retaining his strong compositional sense, his brushwork became more visible and expressive, and his engagement with light and color showed influences beyond the purely illustrative. Some later landscapes and figure studies reveal an awareness of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist currents, perhaps echoing the explorations of light by American Impressionists like Childe Hassam or the powerful landscape forms of Winslow Homer, though Wyeth always retained his distinctive narrative focus. He experimented with different mediums, including egg tempera, a technique later favored by his son Andrew.

Beyond Illustration: Murals and Easel Painting

Although illustration brought him fame and financial security, Wyeth harbored ambitions as a painter of large-scale murals and independent easel works. He sought recognition beyond the pages of books and magazines, undertaking significant mural commissions that allowed him to work on a grander scale. Notable examples include historical panels for the Missouri State Capitol, decorative murals for the Hotel Traymore in Atlantic City, and spiritual themes for the National Episcopal Cathedral in Washington, D.C. He also created striking fireplace overmantels, such as the one for the Franklin Savings Bank in New York.

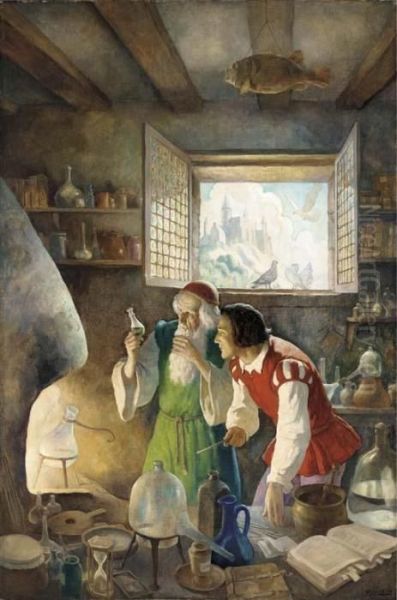

His non-commissioned easel paintings often explored more personal themes and allowed for greater stylistic experimentation. Landscapes of the Brandywine Valley and the coast of Maine were frequent subjects, rendered with a deep sensitivity to place and atmosphere. Works like A House of Eight Corners (1936) showcase his skill in capturing the quiet beauty of rural architecture and landscape. He also tackled symbolic and allegorical subjects, as seen in The Alchemist (1937), and even explored darker themes, as in the early, atmospheric The Opium Smoker (1913). These works reveal a broader artistic vision beyond the demands of illustration.

Life in Chadds Ford: Family and Studio

In 1908, N.C. Wyeth purchased eighteen acres of land in the picturesque Brandywine Valley near Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, an area intimately associated with his teacher, Howard Pyle. Here, he built the home and studio that would become the center of his personal and professional life for nearly four decades. The rolling hills, meandering Brandywine Creek, and historic farmsteads of the region provided constant inspiration for his landscapes and served as the backdrop for his family life.

In 1906, Wyeth married Carolyn Bockius of Wilmington. Together, they raised five talented children: Henriette, Carolyn, Nathaniel, Ann, and Andrew. The Wyeth household was a hub of creative activity, with N.C. actively encouraging his children's artistic pursuits. The family and the surrounding landscape became frequent subjects in his work, reflecting the deep connection he felt to his home and loved ones. His studio, filled with props, costumes, and sketches, was the engine room of his prolific output, a space where imagination took tangible form.

The Wyeth Dynasty: Teaching and Legacy

N.C. Wyeth's influence extended profoundly through his role as a teacher, primarily to his own children. While he didn't run a formal school like Pyle, he provided rigorous, Pyle-inspired training within the family circle. His most famous pupil was his youngest son, Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009), who became one of the most celebrated American realist painters of the 20th century, known for iconic works like Christina's World. N.C.'s daughters also pursued artistic careers: Henriette Wyeth Hurd (1907-1997) became a noted portraitist and still-life painter, married to artist Peter Hurd (1904-1984), another artist who received guidance from N.C. Wyeth. Carolyn Wyeth (1909-1994) developed a distinctive, bold style as a painter. Ann Wyeth McCoy (1915-2005) was both a painter and composer, married to artist John W. McCoy (1910-1989), also mentored by N.C.

This remarkable concentration of talent established the Wyeths as a true American artistic dynasty. The tradition continued with N.C.'s grandson, James (Jamie) Wyeth (b. 1946), son of Andrew, who also achieved fame as a realist painter. N.C. Wyeth's legacy, therefore, includes not only his own vast body of work but also the nurturing of subsequent generations who carried forward the Brandywine tradition of representational art, each developing their own unique voice while acknowledging their artistic roots.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

N.C. Wyeth worked during a dynamic period in American art. While deeply influenced by Howard Pyle, his career unfolded alongside various artistic movements. The Golden Age of Illustration saw him competing and collaborating with talents like Maxfield Parrish, Jessie Willcox Smith, Elizabeth Shippen Green (another prominent Pyle student), and Frank Schoonover. His dramatic narrative style contrasted with the burgeoning Ashcan School, led by figures like Robert Henri and including artists such as George Bellows, who focused on gritty urban realism.

Wyeth also worked concurrently with artists exploring modernism, though his own style remained largely representational. While European modernism was making inroads, and American artists were experimenting with abstraction, Wyeth continued to champion narrative painting and illustration rooted in realism and historical romanticism. His involvement with the Division of Pictorial Publicity during World War I, creating posters alongside artists like Arthur Norman Edrop, placed him within the national effort, using his skills for public communication. His enduring popularity suggests a public appetite for the narrative clarity and evocative power his work provided, even as artistic trends shifted elsewhere.

Tragic End and Enduring Influence

N.C. Wyeth's prolific life and career came to an abrupt and tragic end on October 19, 1945. While driving near his Chadds Ford home, his car stalled on a railroad crossing and was struck by a train. Both Wyeth and his young grandson, Newell Convers Wyeth II (son of Nathaniel), were killed instantly. The loss devastated his family and sent shockwaves through the art world. He was just shy of his 63rd birthday, still actively painting and illustrating.

Despite his untimely death, N.C. Wyeth left behind an immense and influential body of work. His illustrations for Scribner's and other publishers remain definitive visual interpretations of classic tales. His paintings capture a vital sense of American history and landscape. He stands as a pivotal figure in American illustration, bridging 19th-century romanticism with 20th-century popular culture. His legacy is preserved not only in museums and private collections but also at the Brandywine River Museum of Art in Chadds Ford, which holds a major collection of works by him and his family, ensuring his powerful vision continues to inspire.

Conclusion: A Master Storyteller in Paint

Newell Convers Wyeth was far more than an illustrator; he was a master storyteller who used paint and canvas to transport viewers to worlds of adventure, history, and natural beauty. From the decks of pirate ships to the vast plains of the American West, his art captured a sense of drama and authenticity that resonated deeply with the public. Mentored by the great Howard Pyle, he absorbed the best of the Brandywine tradition and forged his own powerful, recognizable style. His work defined classic literature for generations, established an enduring artistic dynasty, and left an indelible mark on American visual culture. N.C. Wyeth's legacy endures in the timeless appeal of his images, which continue to speak of heroism, imagination, and the enduring spirit of America.