William Hogarth stands as a towering figure in the annals of British art history. Living and working during a vibrant period of social change and urban growth (1697-1764), he was far more than just a painter and printmaker; he was a sharp-eyed satirist, a moral commentator, an innovator in narrative art, and a crucial advocate for artists' rights. Often hailed as the "Father of English Painting," Hogarth carved out a unique path, rejecting the dominance of foreign artistic styles and focusing instead on the bustling, complex, and often contradictory life of 18th-century London. His work provides an unparalleled visual record of his time, filled with wit, energy, and a profound understanding of human nature.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

William Hogarth was born in the heart of London, near Smithfield Market, on November 10, 1697. He was the fifth child of Richard Hogarth, a schoolmaster and classical scholar originally from the north of England. Richard's academic pursuits, including an unsuccessful attempt to run a Latin-speaking coffee house, led the family into financial difficulties, culminating in a period spent in the Fleet Prison for debt during William's youth. This early exposure to hardship and the precariousness of London life undoubtedly shaped Hogarth's worldview and fueled his later critiques of social inequality and folly.

Despite the family's financial constraints limiting his formal education, Hogarth displayed a natural talent for drawing from a young age. Rather than pursuing a traditional academic path, he was apprenticed around 1712 to Ellis Gamble, a silverplate engraver in Cranbourne Alley, Leicester Fields. Here, he learned the intricate craft of engraving coats of arms, monograms, and decorative motifs onto silver. While mastering the technical skills of engraving, Hogarth found the repetitive nature of the work stifling to his creative ambitions. He later recalled developing a mnemonic system for remembering visual forms, honing his observational skills even outside of direct drawing practice.

By 1719 or 1720, Hogarth had completed his apprenticeship and set himself up as an independent engraver. He initially undertook trade work like shop cards, billheads, and book illustrations. Seeking to improve his artistic skills beyond mere craft, he began attending private drawing schools, notably the academy in St Martin's Lane established by Louis Chéron and John Vanderbank, and later, Sir James Thornhill's free academy in Covent Garden. Though influenced by the prevailing French and Dutch styles taught there, Hogarth was already developing his own distinctively English voice.

Marriage and Establishing a Career

A pivotal moment in Hogarth's personal and professional life occurred on March 23, 1729. He secretly married Jane Thornhill, the daughter of Sir James Thornhill. Sir James was a highly respected figure in the London art world, holding the prestigious position of Serjeant Painter to the King and renowned for his large-scale historical decorations, such as those at the Painted Hall in Greenwich and the dome of St Paul's Cathedral. The marriage was initially conducted without Sir James's consent, likely due to Hogarth's relatively humble status compared to the established Thornhill family.

However, the rift did not last long. Jane's mother seems to have facilitated a reconciliation, possibly aided by Hogarth's growing reputation. The marriage proved to be a long and supportive one, lasting nearly four decades until Hogarth's death, although the couple remained childless. Jane herself was reportedly an artist, and her connection to the upper echelons of the art world undoubtedly benefited Hogarth. The couple initially lived with the Thornhills in the Great Piazza, Covent Garden, before moving to their own premises at the sign of the Golden Head in Leicester Fields in 1731, which would remain Hogarth's primary London home and studio.

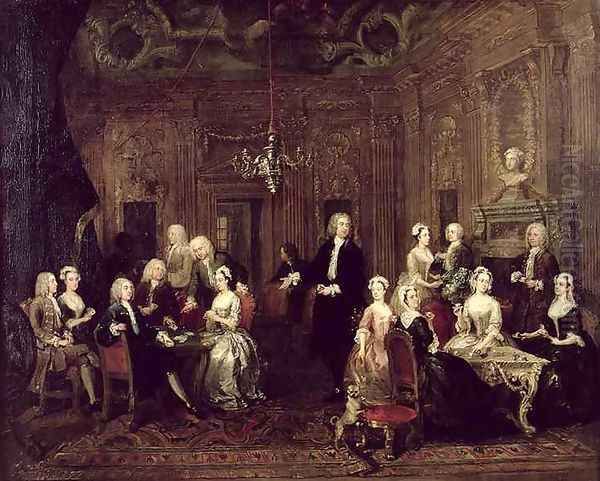

Around the time of his marriage, Hogarth began to shift his focus from engraving the designs of others towards creating his own compositions, particularly in oil painting. He started producing small-scale group portraits, known as "conversation pieces," which depicted families or groups of friends in informal settings. These works, like The Wollaston Family (1730) and The Fountaine Family (c. 1730-35), were innovative in their relaxed naturalism compared to the stiff formality often seen in portraiture of the time.

His true breakthrough, however, came in 1731 with the completion of a series of six paintings titled A Harlot's Progress. This series marked the invention of what Hogarth called his "modern moral subjects" – narrative sequences that told a story, usually with a satirical edge and a cautionary moral. A Harlot's Progress depicted the tragic downfall of a fictional country girl, Moll Hackabout, who arrives in London innocent but is soon drawn into prostitution, leading ultimately to disease, prison, and an early death. The paintings were an immediate sensation, and Hogarth capitalized on their popularity by producing engraved versions, which sold in vast numbers, cementing his fame and financial independence.

The Moralist and Satirist

Following the success of A Harlot's Progress, Hogarth embarked on further "modern moral subjects," solidifying his reputation as London's foremost visual satirist and commentator. In 1735, he published the engravings of A Rake's Progress, an eight-part series charting the decline and fall of Tom Rakewell, a young man who inherits a fortune only to squander it on gambling, prostitutes, and high living, ending his days in the notorious Bethlem Hospital (Bedlam). Like its predecessor, the series was a biting critique of extravagance, vice, and the destructive allure of city life.

Perhaps his most celebrated series is Marriage A-la-Mode, painted between 1743 and 1745 and engraved shortly after. In these six intricate scenes, Hogarth turned his satirical gaze upon the upper classes, specifically targeting the practice of arranged marriages based on wealth and status rather than love. The series follows the disastrous union between the daughter of a wealthy merchant and the son of an impoverished nobleman, Viscount Squanderfield. Their loveless marriage leads to infidelity, disease, murder, and suicide. The paintings are masterpieces of detailed observation, filled with symbolic objects and visual clues that enrich the narrative and underscore the moral decay depicted. Today, the original paintings are a highlight of the National Gallery in London.

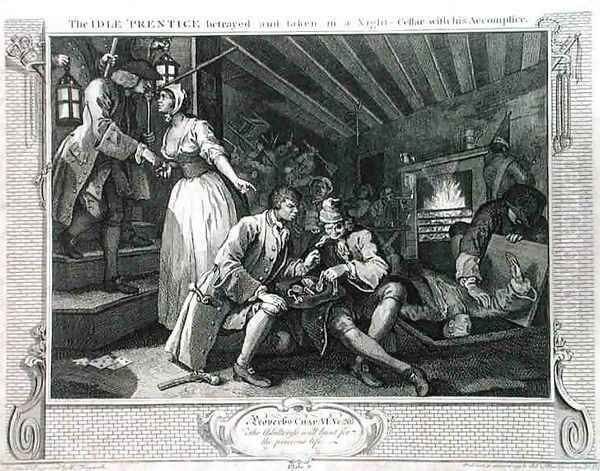

Hogarth continued to explore social themes in other series and individual prints. The Four Times of Day (1738), created with the assistance of the landscape painter George Lambert for Vauxhall Gardens, humorously depicted scenes in different parts of London at morning, noon, evening, and night, capturing the city's diverse life and characters. Industry and Idleness (1747), a series of twelve prints aimed at apprentices, contrasted the virtuous path of the diligent worker with the ruinous fate of his lazy counterpart.

Throughout these works, Hogarth employed a style that was both realistic and theatrical. He staged his scenes like a playwright, using expressive gestures, detailed settings, and carefully arranged compositions to convey the story and the characters' inner states. His satire was often sharp, but usually tempered with humour and a degree of empathy, inviting viewers to reflect on the follies and vices of their society rather than simply condemning them. He saw his art as having a didactic purpose, aiming to entertain and instruct simultaneously.

Portraiture and Conversation Pieces

While best known for his satirical narratives, Hogarth was also a highly accomplished portrait painter. His early success with conversation pieces demonstrated his ability to capture likenesses and convey personality in a more relaxed and naturalistic manner than many of his contemporaries. The engraver and antiquary George Vertue, a contemporary who chronicled the London art scene, praised Hogarth in the early 1730s as being highly skilled and popular in painting "small family pieces & Conversations with portraits."

Hogarth brought this directness and psychological insight to his individual portraits as well. His famous self-portrait, The Painter and His Pug (1745, Tate Britain), is a brilliant example. He presents himself not in the guise of a learned gentleman artist, but informally, in his working cap. His own portrait appears on an oval canvas resting on books by Shakespeare, Swift, and Milton, aligning himself with great English creative minds. Beside him sits his beloved pug dog, Trump, often interpreted as a symbol of Hogarth's own pugnacious and independent spirit.

Another remarkable portrait is The Shrimp Girl (c. 1740-45, National Gallery, London). This unfinished oil sketch captures the lively energy of a young street vendor with astonishing freshness and spontaneity. The loose, fluid brushwork and warm palette differ significantly from the tighter finish of his commissioned works, revealing a more painterly aspect of his talent and his ability to capture fleeting expressions and character.

He also painted more formal portraits, including notable figures like the philanthropist Captain Thomas Coram (1740, Foundling Museum), a work Hogarth considered one of his best, demonstrating his ability to convey dignity and benevolence. However, he often expressed frustration with the vanity of portrait sitters and the constraints of commissioned work, preferring the freedom of his narrative subjects. His approach contrasted with the more flattering, idealized style favoured by some contemporaries like Allan Ramsay or the highly successful Thomas Hudson (master of Joshua Reynolds).

Artistic Theory: The Analysis of Beauty

Hogarth was not content merely to practice art; he also sought to understand and articulate its underlying principles. In 1753, he published The Analysis of Beauty, a treatise that aimed to establish objective principles of visual aesthetics, challenging the prevailing Neoclassical ideals and the authority of traditional art theorists and connoisseurs. The book grew out of his observations and teaching experiences, particularly at the St Martin's Lane Academy, which he helped re-establish after his father-in-law's death.

Central to Hogarth's theory was the concept of the "Line of Beauty," a serpentine or S-shaped curve that he believed embodied grace and visual pleasure. He argued that this line, along with principles such as fitness, variety, uniformity, simplicity, intricacy, and quantity, contributed to the beauty of objects, whether natural or man-made. He illustrated his ideas with two complex engraved plates filled with diverse examples, from classical sculptures to everyday objects and human figures.

The Analysis of Beauty was controversial and met with mixed reactions. Some critics ridiculed its empirical approach and perceived challenge to established taste. However, it was also influential, being translated into several languages and stimulating debate about aesthetics across Europe. It remains a significant text, notable as one of the first attempts by a practicing British artist to articulate a comprehensive theory of visual form based on observation and experience, rather than adherence to classical rules. It asserted the value of variety and complexity over rigid symmetry and simplicity.

Advocacy and the "Hogarth Act"

Hogarth's success with engraved versions of his paintings brought him face-to-face with a major problem in the 18th-century art market: piracy. Unscrupulous publishers quickly produced cheap, unauthorized copies of his popular prints like A Harlot's Progress, depriving him of income and damaging his artistic reputation through poor-quality reproductions. This widespread practice affected many engravers and designers.

Frustrated by these piracies, Hogarth became a leading advocate for legal protection for artists. He lobbied Parliament, alongside fellow artists and printmakers, for legislation to grant creators control over the reproduction of their work. Their efforts were successful, leading to the passage of the Engravers' Copyright Act in 1735. This landmark legislation, often referred to as "Hogarth's Act," granted engravers copyright protection for their original designs for a period of fourteen years.

Hogarth deliberately delayed the publication of the engravings for A Rake's Progress until the Act came into effect, ensuring he could benefit from its protection. The Act was a crucial step in establishing intellectual property rights for visual artists in Britain and is considered one of the world's earliest specific copyright laws. It demonstrated Hogarth's practical business sense and his commitment to improving the professional standing of artists. His actions helped foster a more stable market for original prints and encouraged artistic innovation.

Contemporaries and the London Art Scene

Hogarth operated within a dynamic London art world populated by native talents and visiting European artists. His relationship with his father-in-law, Sir James Thornhill, was foundational, providing both training and connections. He associated with fellow artists and connoisseurs at venues like Slaughter's Coffee House and the Rose and Crown Club, whose members included the engraver and antiquary George Vertue, the Swedish-born portraitist Michael Dahl, and the Flemish landscape and battle painter Peter Tillemans.

He collaborated with artists like the landscape painter George Lambert and the decorative painter Francis Hayman on projects such as the supper-box paintings for Vauxhall Gardens. Hayman, like Hogarth, was instrumental in the running of the St Martin's Lane Academy, a crucial training ground for the next generation of British artists, including Thomas Gainsborough and Richard Wilson.

Hogarth's fiercely independent and sometimes combative nature also led to rivalries and disputes. He was critical of the prevailing taste for Old Master paintings and the influence of connoisseurs who, he felt, undervalued native British talent. His patriotism sometimes bordered on xenophobia, particularly towards French and Italian artistic influence. He famously clashed with the radical politician and satirist John Wilkes and his associate, the poet Charles Churchill, in the early 1760s. After Hogarth published a print critical of Wilkes (The Times, Plate 1), Churchill retaliated with a scathing poetic epistle attacking Hogarth personally and professionally. Hogarth responded with a biting engraved portrait of Wilkes, depicted with demonic horns and a leering expression.

In the field of portraiture, he competed with successful painters like Thomas Hudson and the Scottish artist Allan Ramsay. While Hogarth offered psychological depth and realism, their smoother, more elegant style often proved more popular with aristocratic patrons. The London art scene during his lifetime also saw the presence of prominent foreign artists like the Venetian view-painter Canaletto, whose detailed depictions of the city offered a different perspective from Hogarth's narrative focus. Hogarth's work, particularly its Rococo elements of asymmetry and serpentine lines, shows an awareness of contemporary French artists like Jean-Antoine Watteau, though transformed into a distinctly English idiom.

Later Life and Anecdotes

In 1749, Hogarth purchased a country retreat, a modest brick house in Chiswick, then a village west of London. This house, now Hogarth's House museum, provided an escape from the bustle of Leicester Fields. He and Jane spent increasing amounts of time there, especially in the summer months. He continued to paint and engrave, though his output slowed somewhat in his later years. In 1757, he achieved a measure of official recognition when he was appointed Serjeant Painter to the King, the same prestigious court position previously held by his father-in-law.

Anecdotes from his life paint a picture of a man who was observant, witty, and fiercely independent, though perhaps sometimes forgetful or quick-tempered. One story tells of him being unable to capture a particular expression for A Harlot's Progress, resorting to sketching it directly onto the canvas with his thumbnail. Another relates his humorous, perhaps slightly mocking, interaction with a physician after a meal. A tale involving a planned visit to a mayor (possibly a Mr. Burton) being thwarted by a sudden storm highlights a potential absent-mindedness. His fantasy of drinking beer in heaven with fellow satirists like Shakespeare, Swift, and Voltaire reveals his literary affinities and self-perception. Even the possible origin of his wife's name, Jane, from a humorous nickname "Hogherd," hints at a playful side to his personality.

His final years were marked by declining health and the bitter controversy with Wilkes and Churchill. His last major print, Tailpiece, or The Bathos (1764), published shortly before his death, is a pessimistic allegory depicting the end of all things, a world consumed by chaos and decay. William Hogarth died suddenly at his home in Leicester Fields on October 26, 1764, shortly after returning from his house in Chiswick. He was buried in the churchyard of St Nicholas' Church, Chiswick.

Legacy and Influence

William Hogarth's impact on British art and culture is immense and multifaceted. As the "Father of English Painting," he asserted a distinctly national artistic identity, breaking free from dependence on continental models. He pioneered the genre of satirical narrative sequences, using visual art to comment powerfully on contemporary society, morality, and politics. His "modern moral subjects" laid the groundwork for the great age of British caricature that followed, profoundly influencing artists like James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson.

His commitment to realism, particularly in portraiture and the depiction of everyday life, injected a new vitality into British painting. His ability to tell complex stories through intricate visual detail influenced later narrative painters, including Victorian artists like William Powell Frith and perhaps even the Pre-Raphaelites like John Everett Millais in their attention to symbolic detail.

Beyond his artistic output, Hogarth's The Analysis of Beauty remains a significant contribution to aesthetic theory, championing principles of variety and intricacy. His successful campaign for the Engravers' Copyright Act had lasting legal and economic consequences for artists' rights. He was the first British-born artist to achieve widespread international recognition during his lifetime, with his prints circulating throughout Europe and the American colonies.

Today, Hogarth's works are celebrated for their artistic skill, their narrative power, their satirical wit, and their invaluable insight into the society of Georgian England. He remains a pivotal figure, studied not only by art historians but also by social historians, literary scholars, and anyone interested in the vibrant, complex world he so brilliantly captured. His legacy endures in the term "Hogarthian," used to describe scenes of bustling, satirical, and often darkly humorous social observation.

Conclusion

William Hogarth was a true original – an artist, theorist, satirist, and social commentator whose work fundamentally shaped the course of British art. From his early days as an engraver to his triumphs with narrative series like A Harlot's Progress and Marriage A-la-Mode, he forged a unique path defined by keen observation, moral purpose, and fierce independence. His paintings and prints offer a vivid, unflinching, and often humorous portrayal of 18th-century London life, while his theoretical writings and advocacy for artists' rights demonstrate his intellectual engagement with his profession. More than just the "Father of English Painting," Hogarth remains a vital voice, his work continuing to resonate with its timeless exploration of human nature and societal critique.