An Artist's Journey: From Scotland to the Sierras

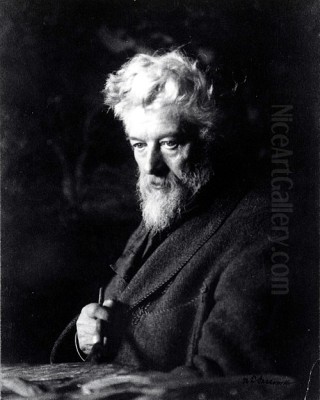

William Keith, a name synonymous with the majestic beauty of California's landscapes, stands as a pivotal figure in American art history. Born in Oldmeldrum, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, on November 18, 1838, his life journey took him across the Atlantic and eventually led him to become one of the most celebrated painters of the American West. His artistic evolution mirrors the changing artistic tastes of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, moving from detailed realism towards a more subjective and spiritual interpretation of nature.

Keith's early life was marked by migration. Following his father's death shortly before his birth, his family faced challenging times. In 1850, seeking better opportunities, his mother brought William and his sisters to New York City. This move proved formative. Young Keith soon showed an aptitude for detailed work, leading him to an apprenticeship as a wood engraver around 1856. This trade provided him with technical skills in line, form, and composition that would subtly inform his later work in painting.

The lure of the West, burgeoning with opportunity and dramatic scenery, called to Keith. Around 1858 or 1859, he made the significant move to San Francisco. Initially, he continued his work as an engraver, contributing illustrations to publications like Harper's Weekly. This work required him to travel and observe, likely sharpening his eye for landscape detail. It was during this period that the seeds of his passion for painting, particularly landscape painting, began to germinate.

The Transition to Canvas and European Horizons

By the mid-1860s, Keith's interest in painting had solidified. He began formal studies around 1863, seeking to master the techniques of oil and watercolor. A key figure in his early personal life and artistic development was Elizabeth Emerson, whom he married in 1864. Elizabeth was herself an amateur artist, and sources suggest she provided encouragement and perhaps even initial instruction, particularly in watercolor techniques.

Recognizing the need for more formal training and exposure to established art traditions, Keith made the decision to travel abroad. In 1868, he largely abandoned engraving to dedicate himself fully to painting. The following year, from 1869 to 1871, he immersed himself in the European art scene, primarily studying in Düsseldorf, Germany. This was a significant center for landscape painting, known for the Düsseldorf School, which emphasized detailed realism and often dramatic, narrative elements in landscapes.

In Düsseldorf, Keith studied with notable German painters, including Albert Flamm and possibly Andreas Achenbach or Oswald Achenbach, both masters of the Düsseldorf style. However, his time in Europe also exposed him to other influential movements. He encountered the works of the French Barbizon School painters, such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Jean-François Millet, and Charles-François Daubigny. Their approach, emphasizing mood, atmosphere, and a more direct, less idealized portrayal of rural landscapes, resonated deeply with Keith and marked a crucial influence that would blossom more fully in his later career. He also spent time in Munich and possibly Paris, further broadening his artistic horizons.

California Beckons: The Early Grand Manner

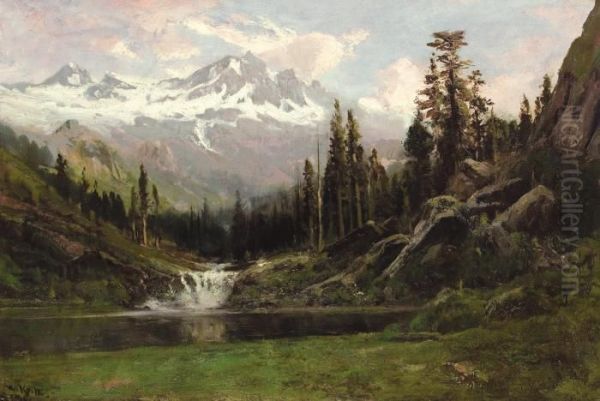

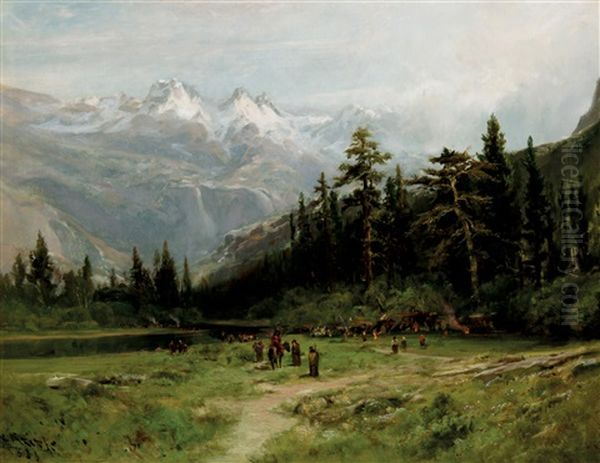

Returning to California around 1872, Keith established himself in San Francisco, which would remain his base for the rest of his life. He brought back with him enhanced technical skills and a broadened artistic perspective. His early California works often reflected the influence of the Düsseldorf School and the prevailing taste for grand, panoramic views, akin to the works of Hudson River School painters like Albert Bierstadt and Frederic Edwin Church, who were also drawn to the monumental landscapes of the American West.

During the 1870s, Keith produced many of his "epic" canvases, depicting the towering granite cliffs of Yosemite, the vast expanses of the High Sierra, and the dramatic scenery of the Pacific Northwest. He undertook commissions, including work for the Northern Pacific Railroad, which involved documenting the landscapes along its routes. These paintings were characterized by meticulous detail, a clear rendering of light, and a sense of awe inspired by the untamed wilderness. They captured the public imagination and quickly established Keith's reputation as a leading landscape painter on the West Coast.

His commitment to capturing the essence of California's wilderness led him to undertake numerous sketching trips into the mountains. An important companion on some of these early expeditions was the photographer Carleton Watkins. Traveling together in 1873-74, they explored regions like the Sierra Nevada and the California Missions, each capturing the landscape through their respective mediums. This period solidified Keith's deep connection to the specific geography and atmosphere of California.

The Muir Connection: Art, Nature, and Friendship

Perhaps the most significant relationship in William Keith's life, outside of his family, was his deep and enduring friendship with the naturalist, writer, and conservationist John Muir. They likely first met in Yosemite Valley in 1872. Both men were Scottish immigrants who shared a profound, almost spiritual reverence for the natural world, particularly the Sierra Nevada. Their meeting sparked an immediate connection.

Over the next decades, Keith and Muir embarked on numerous trips together into the High Sierra, exploring Yosemite, Hetch Hetchy Valley, and other remote areas. Muir, the scientist and keen observer, would study the geology and botany, while Keith, the artist, would sketch and absorb the scenery, light, and atmosphere. Their conversations and shared experiences deeply influenced both men.

Muir admired Keith's ability to capture the spirit and grandeur of the landscapes they both loved, often praising his work effusively. He sometimes critiqued Keith for not being "scientific" enough in his depictions, but ultimately respected the emotional truth Keith conveyed. Conversely, Muir's detailed knowledge and passionate advocacy for wilderness preservation undoubtedly informed Keith's understanding and appreciation of the landscapes he painted. Keith became an artistic voice for the conservation movement, creating powerful images of places like Hetch Hetchy Valley that Muir was fighting to protect. Their friendship was a unique blend of art, science, and shared passion for the California wilderness.

The Bohemian Club and Artistic Community

Upon settling back in San Francisco in 1872, William Keith became an active member of the city's burgeoning cultural scene. He joined the Bohemian Club, a private club that brought together artists, writers, musicians, journalists, and patrons of the arts. The Club provided a vital social and professional network for Keith, offering opportunities to exhibit his work, connect with potential buyers, and engage in intellectual and artistic discussions.

The Bohemian Club played a significant role in promoting Californian artists, and Keith was one of its most esteemed members. He regularly participated in the Club's exhibitions and social events. His studio became a gathering place for fellow artists and admirers. Through the Club and his growing reputation, Keith interacted with many other artists and cultural figures of the time, contributing to the vibrant artistic milieu of late 19th-century San Francisco. While specific records of extensive collaborations might be sparse, his position placed him at the center of the West Coast art world.

A Shift Towards Subjectivity: Tonalism and Spirit

The 1880s marked a period of significant personal and artistic transition for Keith. Tragedy struck in 1882 with the death of his first wife, Elizabeth. The following year, he married Mary McHenry, a prominent figure in her own right, who was one of the first female graduates of Hastings Law School and an active suffragist. Mary became a steadfast supporter of Keith's work and later played a crucial role in preserving his legacy.

Artistically, Keith's style began to evolve away from the detailed, panoramic views of his earlier period. He became increasingly interested in conveying the mood and emotional essence of the landscape rather than a purely topographical representation. This shift aligned him with the burgeoning Tonalist movement in American art. Tonalism, practiced by artists like George Inness and James McNeill Whistler, favored intimate scenes, muted color palettes, soft edges, and an emphasis on atmosphere and poetic feeling.

A key influence during this period was the Reverend Joseph Worcester, a Swedenborgian minister and an influential figure in Bay Area cultural circles. Worcester became a close friend and spiritual mentor to Keith after Elizabeth's death. Swedenborgianism, with its emphasis on the correspondence between the natural and spiritual worlds, resonated with Keith's own deepening spiritual inclinations and his desire to imbue his landscapes with deeper meaning. Worcester also acted as an advisor and helped promote Keith's work, guiding him towards patrons who appreciated his evolving style.

The encounter with the renowned landscape painter George Inness in 1890 or 1891 proved particularly pivotal. Inness, a leading proponent of Tonalism and also influenced by Swedenborgian ideas, visited California and spent several weeks working and sketching alongside Keith. This direct interaction with Inness solidified Keith's move towards a more subjective, spiritual, and Tonalist approach. His later works often feature intimate woodland interiors, misty meadows, and evocative sunsets or moonrises, rendered in rich, dark tones with dramatic plays of light and shadow. He sought to capture the "soul" of the landscape, reflecting his inner response to nature's spiritual qualities. He also continued to admire and study the atmospheric effects in the works of the British master J.M.W. Turner.

Masterworks of Mood and Spirit

William Keith's prolific output includes thousands of paintings, but certain works stand out as particularly representative of his mature style and thematic concerns.

_Evening Glow_: This painting exemplifies Keith's later Tonalist style. It depicts a forest interior bathed in the warm, diffused light of sunset. The details of individual trees merge into masses of shadow and light, creating a powerful sense of atmosphere and mystery. The focus is not on specific features but on the overall mood – quiet, contemplative, and imbued with an almost religious solemnity. It showcases his mastery of light and shadow to evoke emotion.

_The Soul of Music_: While the exact subject matter might be allegorical, this title suggests Keith's interest in conveying abstract concepts and emotions through landscape. Likely employing rich color harmonies and dynamic light effects, the work probably aimed to translate the emotive power of music into visual terms. It reflects the late 19th-century interest in synesthesia and the connections between different art forms, expressing inner states and spiritual dimensions through color and light.

_Gethsemane_: This title, referencing the biblical garden where Jesus prayed before his crucifixion, indicates a work with strong spiritual or religious overtones. It might depict a dark, stormy landscape or a scene imbued with a sense of struggle and contemplation, using nature as a metaphor for spiritual trial or inner turmoil. Such works highlight Keith's engagement with Swedenborgian ideas and his use of landscape to explore profound themes of faith, suffering, and redemption. These paintings demonstrate his move beyond mere representation towards symbolic and deeply personal expression.

Teaching and Influence

Beyond his own painting, William Keith also contributed to the development of art in California as a teacher. Unusually for the time, he primarily accepted female students. He maintained separate studio spaces and dedicated time to instructing women artists in the techniques of landscape painting. This focus provided important opportunities for women seeking professional art training in an era when such avenues could be limited.

His students benefited from his extensive experience and his evolving artistic philosophy. He encouraged them to observe nature closely but also to interpret it through their own sensibilities. While not establishing a formal "school" in the academic sense, his guidance helped shape the next generation of California artists, particularly women painters seeking to capture the unique landscapes of the state.

The Great Fire and Later Years

A devastating blow struck Keith's career and legacy in 1906. The great San Francisco earthquake and subsequent fire destroyed vast swathes of the city, including Keith's studio and gallery on Pine Street. It is estimated that over 2,000 of his works – paintings, sketches, and studies spanning his entire career – were lost in the disaster. This represented an irreplaceable archive of his artistic development and a significant portion of his life's work.

Despite this immense loss and the trauma of the event, Keith, then in his late 60s, continued to paint with determination in the remaining years of his life. He established a new studio in Berkeley, across the bay from the ruined city. His late works continued in the Tonalist vein, often characterized by deep, resonant colors and a focus on the intimate, spiritual aspects of nature. He remained a revered figure in the California art scene, often referred to as the "Dean of California Artists" or the "Father of California Painters."

His fame was such that his work was widely sought after, leading inevitably to issues with imitators and forgeries, a testament to his high standing in the art market. He continued exhibiting his work and remained a respected elder statesman of American landscape painting until his death.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

William Keith passed away at his home in Berkeley, California, on April 13, 1911, at the age of 72. He left behind a rich legacy as one of the most important figures in California art history. His journey from a Scottish immigrant engraver to the preeminent landscape painter of the American West is a remarkable story of artistic dedication and evolution.

His work bridged several important art movements, incorporating elements of the Hudson River School's grandeur, the Düsseldorf School's detail, the Barbizon School's atmospheric naturalism, and the subjective spirituality of Tonalism. He captured the unique light and diverse landscapes of California, from its towering mountains to its intimate oak-studded hills and coastal scenes, like few others.

His close friendship with John Muir and his artistic contributions to the early conservation movement highlight the powerful connection between art and environmental awareness. His paintings helped shape the public perception of California's natural beauty and contributed to the appreciation and preservation of its wilderness.

Today, William Keith's paintings are held in numerous major museum collections, including the Saint Mary's College Museum of Art in Moraga (which holds the largest single collection of his work), the Oakland Museum of California, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and many others across the United States. His work continues to be admired for its technical skill, its evocative beauty, and its profound connection to the spirit of the California landscape. He remains a foundational figure for understanding the art of the American West and the development of landscape painting in America.