John Ross Key (1837-1920) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the panorama of nineteenth-century American art. Born into a family already etched into the annals of American history, Key navigated a multifaceted career that saw him transition from a meticulous draftsman and cartographer to a celebrated painter associated with the later phase of the Hudson River School. His life and work offer a fascinating window into the artistic, cultural, and even geopolitical currents that shaped the United States during a period of profound transformation, from westward expansion to the crucible of the Civil War and the burgeoning industrial age. This exploration will delve into his origins, his artistic development, his key works, his relationship with contemporary art movements, and his enduring, though perhaps under-appreciated, legacy.

A Distinguished Lineage and Early Stirrings

John Ross Key was born in Hagerstown, Maryland, on July 16, 1837. His heritage was indeed distinguished. He was the grandson of Francis Scott Key, the lawyer and amateur poet who penned the lyrics to "The Star-Spangled Banner" after witnessing the bombardment of Fort McHenry during the War of 1812. This connection alone placed the young Key within a narrative of American patriotism and historical significance. Further back, his great-grandfather, also named John Ross Key, had served as a judge and a commissioned officer during the American Revolutionary War, cementing the family's deep roots in the nation's foundational struggles.

This familial backdrop, steeped in public service and historical moment, likely instilled in Key a keen awareness of the American landscape and its symbolic importance. From an early age, he exhibited a natural aptitude for drawing. This talent found a practical outlet when, in 1853, at the young age of sixteen, he began working as a draftsman for the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey. This position was crucial, providing him with rigorous training in precision, observation, and the technical skills of rendering terrain – abilities that would profoundly inform his later landscape painting.

Around 1856, Key relocated to New York City, the burgeoning center of the American art world. It is believed that during this period he may have received some formal art instruction, possibly at the prestigious National Academy of Design. The Academy, founded by artists like Samuel F.B. Morse, Thomas Cole, and Asher B. Durand, was the premier institution for aspiring artists in America, offering drawing classes from casts and life, and annual exhibitions that showcased the latest trends in American art. Even if his attendance was brief, exposure to the Academy's environment and the work of established artists would have been invaluable.

The Call of the West: The Lander Expedition

Key's skills as a draftsman and topographer soon led him to participate in one of the great adventures of the era: westward expansion. He joined the Lander Oregon Trail Wagon Road Expedition (1859-1860), led by Colonel Frederick W. Lander. The purpose of these government-sponsored expeditions was manifold: to survey routes for railroads and wagon trails, to document the flora, fauna, and geology of the largely uncharted territories, and to assert American presence.

Artists were often included in these expeditions to create visual records of the landscapes encountered. Key's role involved creating topographical drawings and maps of regions in present-day Nevada and Wyoming. This experience was formative. It exposed him to the raw, monumental beauty of the American West, a landscape vastly different from the more pastoral scenes of the East Coast. He worked alongside other artists on such expeditions, including figures who would become famous for their Western scenes, such as Albert Bierstadt, who also participated in Lander's earlier surveys. Other artists like Henry Hitchings and Francis Seth Frost were also involved in similar government-supported explorations, contributing to a growing visual archive of the nation's expanding frontiers. This direct encounter with the sublime and often challenging Western environment undoubtedly broadened Key's artistic horizons and honed his observational skills under demanding conditions.

Service and Observation: The Civil War Years

The outbreak of the American Civil War (1861-1865) saw John Ross Key apply his specialized skills to the Union cause. He served as an engineer and draftsman, likely with the Corps of Engineers. His most notable contribution during this period was his detailed mapping and panoramic drawings of the Siege of Charleston, South Carolina. Charleston was a key Confederate port, and its protracted siege was a significant military undertaking.

Key's drawings of the Charleston Harbor defenses, fortifications like Fort Sumter and Battery Wagner, and the surrounding terrain were not merely functional military documents; they were also works of considerable artistic merit, demonstrating his keen eye for detail and perspective. Some of these wartime drawings were later published as lithographs in 1863, providing the public with vivid, firsthand visual accounts of the conflict. This experience, documenting scenes of immense historical gravity, further sharpened his ability to capture complex scenes with accuracy and a sense of atmosphere. The war, a defining experience for his generation, undoubtedly left an indelible mark on his worldview and, perhaps subtly, on his later artistic interpretations of nature's grandeur and transience.

The Hudson River School and Its Evolution

Following the Civil War, John Ross Key transitioned more fully into a career as a painter. His artistic sensibilities aligned closely with the prevailing trends in American landscape painting, particularly the Hudson River School. This movement, America's first true school of landscape painting, had emerged in the 1820s, spearheaded by artists like Thomas Cole. Cole, often regarded as the movement's founder, imbued his landscapes with allegorical and moral meaning, drawing inspiration from the Catskill Mountains and the Hudson River Valley. His works, such as "The Course of Empire" series, reflected a Romantic sensibility, celebrating the wildness of American nature while also cautioning against unchecked societal development.

Asher B. Durand, a contemporary of Cole and his successor as the leader of the Hudson River School, advocated for a more direct and faithful representation of nature. Durand encouraged artists to sketch outdoors, directly from nature ("en plein air"), to capture its specific truths. His influential "Letters on Landscape Painting" emphasized detailed observation and a reverence for the American wilderness. Other prominent figures of this first generation included Thomas Doughty, one of the earliest American artists to specialize in landscapes, and Alvan Fisher.

By the time Key was establishing himself as a painter in the late 1860s, the Hudson River School had entered its second generation. These artists, building upon the foundations laid by Cole and Durand, expanded their geographical scope and refined their techniques. They ventured further afield, depicting the landscapes of New England, the White Mountains, the American West, and even South America and the Arctic. Key figures of this second generation included John Frederick Kensett, Sanford Robinson Gifford, Frederic Edwin Church, and Albert Bierstadt.

A New Vision: The Second Generation and Luminism

The second generation of Hudson River School painters often embraced a style that came to be known as Luminism. While not a formally organized movement with a manifesto, Luminism is a term coined by later art historians to describe a characteristic American landscape painting style of the 1850s-1870s. Luminist paintings are distinguished by their meticulous attention to detail, their smooth, often invisible brushwork, and, most importantly, their profound concern with the effects of light and atmosphere.

Luminist artists sought to capture the subtle gradations of light, the reflective qualities of water, and the ethereal haze of a tranquil dawn or a serene sunset. Their compositions are often characterized by a sense of calm, stillness, and an almost spiritual quietude. John Frederick Kensett was a master of this style, renowned for his serene coastal scenes of New England, where light seems to dissolve forms and create a palpable sense of peace. Sanford Robinson Gifford was celebrated for his hazy, atmospheric landscapes, often depicting the glow of the sun through mist or dust, creating a poetic and evocative mood. Fitz Henry Lane, working primarily in coastal New England, particularly Gloucester, Massachusetts, produced crystalline, light-filled marine paintings that are quintessential examples of Luminism. Martin Johnson Heade, another key Luminist, painted evocative salt marsh scenes and, uniquely, tropical landscapes and still lifes featuring orchids and hummingbirds.

Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt, while sometimes associated with Luminist effects, are often distinguished by their creation of grand, panoramic "Great Pictures." Church, a student of Thomas Cole, traveled extensively, painting dramatic vistas of South America (like "Heart of the Andes") and the Arctic ("The Icebergs"). Bierstadt, Key's sometime colleague from the Lander expeditions, became famous for his monumental canvases of the Rocky Mountains and Yosemite Valley, which captured the awe-inspiring scale and drama of the American West. These artists, while diverse in their specific subjects and approaches, shared a common desire to celebrate the unique beauty and grandeur of the American continent, often imbuing their works with a sense of national pride and divine presence in nature.

John Ross Key and the Luminist Aesthetic

John Ross Key's landscape paintings clearly place him within this second generation of the Hudson River School, and his work often exhibits strong Luminist characteristics. After the Civil War, he dedicated himself to capturing the American landscape, and his training as a draftsman and cartographer served him well. His paintings are marked by careful drawing, precise detail, and a sophisticated understanding of perspective.

He was particularly adept at rendering the effects of light on water and land, a hallmark of Luminism. Whether depicting the clear light of California or the more diffused atmosphere of the East Coast, Key demonstrated a sensitivity to the nuances of illumination and its power to define form and evoke mood. His brushwork, while not always as invisible as that of Kensett or Lane, was generally controlled and refined, contributing to a sense of clarity and realism in his scenes. He sought to convey not just the topographical accuracy of a place, but also its inherent beauty and the emotional response it could inspire.

California's Allure: A New Frontier for Art

In 1869, John Ross Key made a significant move, opening a studio in San Francisco, California. The Golden State, with its dramatic coastline, majestic mountains like the Sierra Nevada, and unique light, was becoming an increasingly popular subject for artists. The completion of the transcontinental railroad in that same year made California more accessible, and artists flocked to capture its wonders.

Key was among the vanguard of painters who sought to interpret California's distinctive landscapes. He joined a growing community of artists in San Francisco, which included figures like Thomas Hill, known for his grand Yosemite scenes, and William Keith, whose style evolved from detailed realism to a more Tonalist approach. Albert Bierstadt also made several trips to California, producing some of his most iconic Western paintings there. The allure of California was partly its "newness" to American eyes, offering fresh subjects and a sense of untamed wilderness that resonated with the Hudson River School ethos.

During his time in California, which lasted several years, Key produced a number of important landscapes. He painted views of the San Francisco Bay, the Golden Gate (before the bridge, of course), the rugged coastline, and the interior mountains. These works were well-received and helped to establish his reputation as a skilled landscape painter. His California scenes often emphasize the vastness of the landscape and the clarity of the light, characteristic of the region.

Masterpieces of the West and East

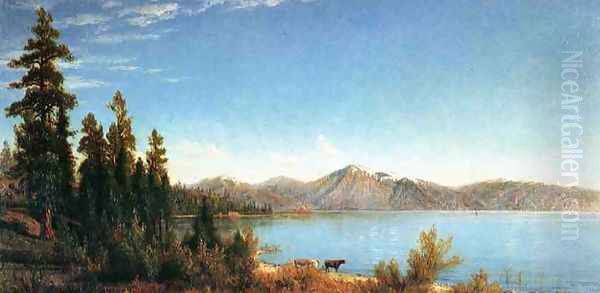

Among John Ross Key's most notable works are his depictions of California. His painting The Golden Gate, San Francisco (circa 1872-73) is a prime example of his California period. It captures the iconic entrance to the San Francisco Bay with a meticulous attention to detail and a luminous quality of light. He also painted other significant California landmarks, such as Mount Shasta and scenes from Yosemite Valley, contributing to the growing visual iconography of the American West. One of his most famous California works is Golden Gate from Telegraph Hill (1873), which showcases his ability to combine panoramic scope with precise rendering.

Key did not limit himself to Western subjects. He also painted landscapes in the East, including scenes in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, a popular sketching ground for Hudson River School artists like Benjamin Champney and Aaron Draper Shattuck. His White Mountain Scenery paintings demonstrate his versatility and his continued engagement with the established traditions of East Coast landscape painting. A work like Lake Tahoe (1873) shows his mastery in capturing the serene beauty of mountain lakes, with reflections and atmospheric depth.

His painting Porto Venere on the Italian Riviera (1880s) indicates that, like many American artists of his time, he also traveled to Europe. Artists such as Sanford Robinson Gifford and Frederic Church also made European tours, seeking to broaden their artistic education and find new subjects. Key’s European scenes, while perhaps less central to his oeuvre than his American landscapes, demonstrate his ability to apply his Luminist-inflected style to different environments.

Beyond Grand Vistas: The Intimacy of Floral Still Lifes

Later in his career, particularly during periods spent in Boston and other East Coast cities, John Ross Key expanded his repertoire to include floral still lifes. This was not an uncommon pursuit for artists of the Victorian era, as still life painting enjoyed considerable popularity, especially for domestic settings. Artists like Martin Johnson Heade, known for his Luminist landscapes, also produced exquisite still lifes of flowers, often in combination with hummingbirds. Severin Roesen was another prominent still life painter of the period, known for his opulent and highly detailed arrangements of fruit and flowers.

Key's floral still lifes, such as Marigolds and Other Wildflowers (1882), are characterized by their delicate rendering, vibrant color, and botanical accuracy. These works reveal a different facet of his artistic sensibility – a capacity for intimate observation and an appreciation for the subtle beauty of smaller natural forms. These paintings were likely aimed at a market that desired art for parlors, dining rooms, and conservatories, reflecting the Victorian era's interest in botany and the decorative arts. His still lifes, while perhaps less ambitious in scale than his landscapes, demonstrate his consistent commitment to realism and his skilled handling of paint.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Throughout his career, John Ross Key actively exhibited his work at prominent venues, gaining recognition for his talents. He showed his paintings at the National Academy of Design in New York, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, and the Boston Art Club. These institutions were central to the American art world, and exhibiting there was crucial for an artist's reputation and sales.

A significant honor came in 1876 when Key was awarded a gold medal at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. This massive international fair, celebrating the 100th anniversary of American independence, featured an extensive art exhibition that showcased the achievements of American artists to a global audience. Receiving a medal at such a prestigious event was a major acknowledgment of his standing in the art community. He also participated in other expositions, such as the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and the Texas State Fair and Dallas Exposition in 1898, further indicating his continued activity and visibility as an artist.

The Power of Print: Collaboration with Louis Prang

An important aspect of John Ross Key's career, and one that helped to disseminate his images to a wider public, was his collaboration with Louis Prang & Co. of Boston. Louis Prang was a pioneering chromolithographer, often called the "father of the American Christmas card." Chromolithography was a complex printing process that allowed for the mass production of color images.

In the 1870s, Prang reproduced a number of Key's landscapes, particularly his California scenes, as chromolithographs. These prints were popular and affordable, making Key's art accessible to a broader audience beyond wealthy collectors of original paintings. This collaboration was significant, as it placed Key's work in homes across America, contributing to the popular visual culture of the time and helping to shape public perceptions of the American landscape. Artists like Eastman Johnson and Winslow Homer also saw their works reproduced through various print media, recognizing the power of prints to reach a wider public.

Later Years and Shifting Focus

John Ross Key never married. In his later years, he divided his time between various cities, including New York, Boston, Chicago, and Baltimore. There is some indication that in his later career, he became more involved in interior decoration. This was not necessarily unusual; many artists in the late 19th century, influenced by movements like the Aesthetic Movement and the Arts and Crafts Movement (popularized by figures like William Morris in England), took an interest in the design of interior spaces and decorative objects.

However, this shift may have led to a perception by some that he was moving away from "fine art" painting. It's possible that this, combined with changing artistic tastes as Impressionism and other modern styles began to gain traction in America, contributed to his work being somewhat overshadowed in the early 20th century. Artists like Childe Hassam and Theodore Robinson were among the American painters who embraced Impressionism, signaling a shift away from the detailed realism of the Hudson River School.

John Ross Key passed away in Baltimore, Maryland, on March 24, 1920, at the age of 82.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Realism and Atmosphere

Summarizing John Ross Key's artistic style, it is clear that he was a product of his time, deeply rooted in the traditions of 19th-century American realism. His early training as a draftsman and cartographer instilled in him a commitment to accuracy, precision, and detailed observation. This foundation is evident in all his work, from his military maps to his grand landscapes and delicate still lifes.

As a landscape painter, he aligned with the second generation of the Hudson River School, and his work frequently displays the key characteristics of Luminism: a concern for the effects of light and atmosphere, smooth brushwork, and often serene, contemplative compositions. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the specific quality of light in different regions, from the crisp, clear illumination of California to the softer, more diffused light of the East Coast or the hazy skies of an Italian vista.

His compositions are generally well-balanced and demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of perspective, undoubtedly honed by his mapmaking experience. While his work may not always achieve the sublime drama of a Bierstadt or a Church, or the profound spiritual quietude of a Kensett at his best, Key consistently produced landscapes of high quality, marked by their fidelity to nature and their pleasing aesthetic. His floral still lifes, though a smaller part of his output, showcase a similar dedication to realistic detail and an appreciation for natural beauty.

Enduring Legacy and Market Presence

For a period in the 20th century, John Ross Key, like many Hudson River School painters, experienced a decline in critical attention as modernist art movements came to dominate. However, the latter half of the 20th century saw a resurgence of interest in 19th-century American art, and Key's work has since been re-evaluated and appreciated anew.

His paintings are now held in the collections of numerous American museums, including the White House Historical Association, the Oakland Museum of California, the New Hampshire Historical Society, and the Morris Museum of Art in Augusta, Georgia. His works also appear on the art market, where they command respectable prices, indicating a continued appreciation among collectors. For instance, auction results, such as the sale of two of his oil paintings for $75,600 at Eldred's, attest to his enduring market value.

John Ross Key's legacy lies in his contribution to the visual record of 19th-century America. His landscapes, whether of the iconic West or the familiar East, capture a nation in the process of defining itself and its relationship with its vast and varied natural environment. His wartime drawings provide valuable historical documentation. His collaboration with Louis Prang helped to popularize landscape art and make it accessible to a wider segment of the population.

Conclusion

John Ross Key was an artist whose career spanned a pivotal era in American history and art. From his distinguished lineage and early training as a draftsman to his participation in Western expeditions, his service in the Civil War, and his mature career as a landscape and still life painter, Key consistently demonstrated a high level of skill and a deep appreciation for the American scene. As a representative of the second generation of the Hudson River School, and an adept practitioner of the Luminist style, he created works that are both historically significant and aesthetically pleasing. While perhaps not always ranked among the very top tier of his contemporaries like Church, Bierstadt, or Kensett, John Ross Key was a talented and dedicated artist who made a valuable contribution to the rich tapestry of American art. His paintings continue to offer viewers a luminous glimpse into the landscapes and artistic sensibilities of 19th-century America.