William Nicholson (1872-1949) stands as a significant yet sometimes underestimated figure in the landscape of British art. A painter and printmaker of remarkable versatility, his career spanned a period of dramatic change in the art world, yet he carved a unique path distinct from the dominant currents of academicism and avant-garde modernism. Renowned for his sophisticated portraits, evocative landscapes, and exquisitely rendered still lifes, Nicholson combined technical brilliance with a subtle humour and innovative spirit. His contributions extended beyond painting to encompass groundbreaking work in graphic arts, particularly woodcuts, leaving an indelible mark on early twentieth-century design and illustration.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Newark-on-Trent, Nottinghamshire, in 1872, William Nicholson hailed from a background of relative comfort; his father was an industrialist and a Conservative Member of Parliament. This environment likely provided him with the stability to pursue an artistic path from a young age. His initial artistic guidance came from William Cubley, a painter based locally. Seeking more formal training, Nicholson enrolled at Hubert von Herkomer's renowned art school in Bushey, Hertfordshire. Herkomer's academy was known for its rigorous approach, providing a solid foundation in technique.

Further broadening his horizons, Nicholson travelled to Paris to study at the prestigious Académie Julian. This period exposed him to the vibrant Parisian art scene and the latest continental trends, although his own style would ultimately retain a distinctly British sensibility. It was during his formative years that he met the Scottish artist Mabel Pryde, sister of the painter James Pryde. William and Mabel married in 1893, embarking on a partnership that was both personal and, indirectly, artistic, placing Nicholson within a circle of creative individuals.

The Beggarstaffs and Revolution in Graphic Art

One of Nicholson's earliest and most impactful contributions came through his collaboration with his brother-in-law, James Pryde. Working under the joint pseudonym "J. & W. Beggarstaff" or simply the "Beggarstaff Brothers," the pair revolutionised poster design in the 1890s. Their approach was radical for its time, characterised by stark simplicity, flattened perspectives, bold silhouettes, and dramatic use of negative space, often executed in black and white or severely limited colour palettes.

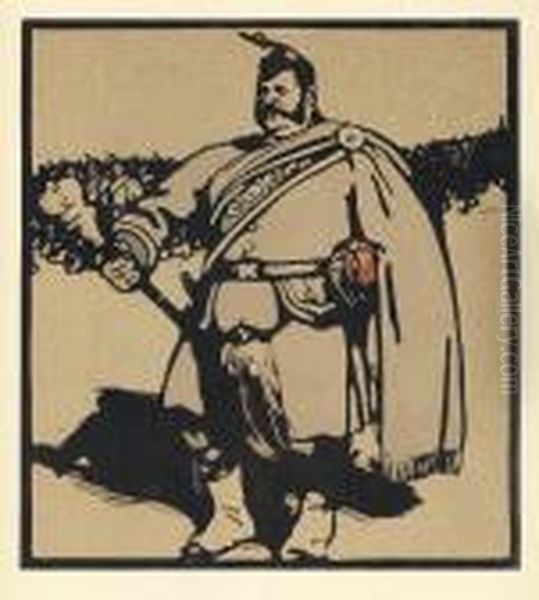

This innovative style drew inspiration from various sources, including the bold compositions found in Japanese woodblock prints and the contemporary work of French artists associated with the Nabis movement, such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. The Beggarstaffs employed techniques like collage, cutting shapes from coloured paper and pasting them down to create powerful, minimalist designs that prioritised immediate visual impact over detailed rendering. Their posters for theatrical productions, like Hamlet and Don Quixote, are iconic examples of modern graphic design.

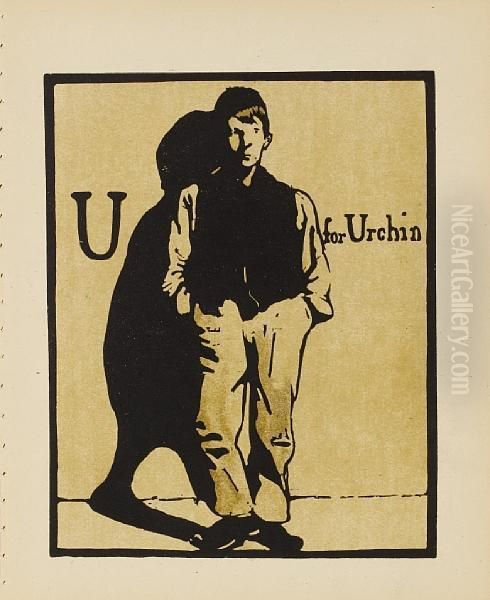

Beyond posters, Nicholson applied his graphic talents to printmaking and illustration. His woodcuts, particularly those in black and white, earned him considerable acclaim. Notable works from this period include the series An Alphabet (1898), a charming children's book pairing letters with memorable woodcut images, An Almanack of Twelve Sports (1898), with verses by Rudyard Kipling, and London Types (1898), a portfolio capturing various London characters with characteristic wit and graphic economy. The Beggarstaffs' bold aesthetic and technical innovations profoundly influenced subsequent generations of graphic designers and printmakers.

Mastery in Painting: Still Life and Landscape

While his graphic work brought early fame, William Nicholson increasingly dedicated himself to painting from the early 1900s onwards. He excelled particularly in the genres of still life and landscape, developing a distinctive style marked by understated elegance, a masterful handling of light and tone, and a keen sensitivity to texture and atmosphere. His approach was neither strictly academic nor overtly modernist, occupying a unique space appreciated for its technical refinement and quiet poetry.

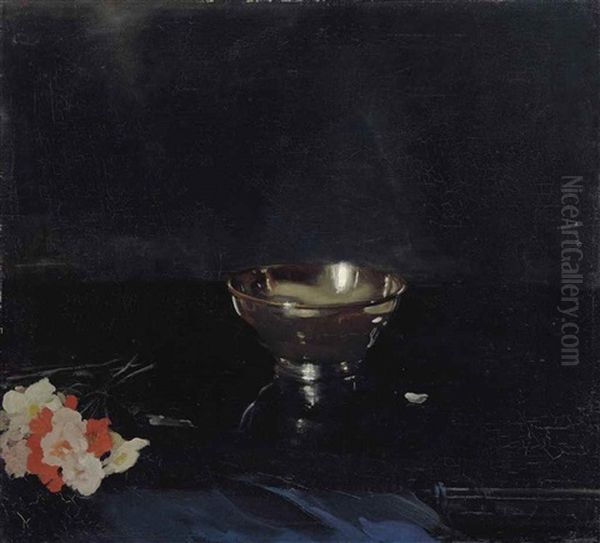

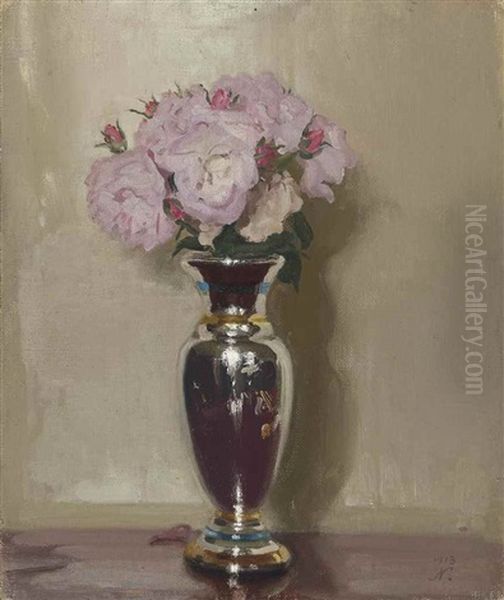

Nicholson possessed an extraordinary ability to elevate everyday objects through his art. His still life compositions often feature simple arrangements – jugs, bowls, flowers, fruit, silverware – rendered with exquisite attention to the play of light on surfaces. Works like The Lustre Bowl, Rose Lustre, and The Silver Casket and Red Leather Box (1920) exemplify his skill in capturing the subtle sheen of ceramics, the delicate texture of petals, or the reflective quality of metal. He imbued these seemingly mundane subjects with a sense of presence and quiet dignity.

His landscapes, often depicting the gentle hills and downs of Southern England or coastal scenes, share this sensitivity to light and atmosphere. Hills above Harlech (1915), for instance, uses soft, harmonious tones and fluid brushwork to convey the dry texture of the grasses and the specific quality of light on the Welsh hills. Other notable landscapes, such as The Bull Ring (Tate), showcase his ability to find compelling compositions in varied settings. His landscapes are rarely dramatic in the Romantic sense; instead, they capture nuanced moods and the quiet beauty of the English countryside with remarkable subtlety.

The Art of Portraiture

Alongside still life and landscape, portraiture formed a crucial part of William Nicholson's oeuvre. He possessed a talent for capturing not just a likeness but also the character and presence of his sitters. His portraits are often characterised by their sophisticated compositions, subtle tonal harmonies, and a sense of psychological insight, achieved without resorting to overt expressiveness. He painted numerous prominent figures of his time, as well as intimate portraits of family and friends.

A notable example of his portrait work is the painting of the poet and writer Siegfried Sassoon. Nicholson met Sassoon in 1918, introduced by their mutual friend, the poet Robert Graves. This marked the beginning of a lasting friendship and occasional collaboration. Nicholson designed the cover for Sassoon's The War Poems, and his portrait of Sassoon, later kept by the poet's family, stands as a sensitive portrayal of the writer. His ability to convey personality through pose, expression, and the handling of paint made him a sought-after portraitist.

Navigating Tradition and Modernity

William Nicholson's artistic journey unfolded during a period of intense artistic experimentation across Europe. While influenced by movements like Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, particularly in his handling of light and colour, he never fully aligned himself with the more radical strands of modernism like Cubism or pure abstraction in the way some of his contemporaries, including his own son, did. His style remained rooted in observation, albeit filtered through a modern sensibility for design and simplification.

Despite this individual path, Nicholson was not isolated from the currents of modern art. He engaged with contemporary developments and participated in significant artistic groups. In 1925, he joined the Seven and Five Society, a group initially formed after World War I that aimed to promote painting with leanings towards continental Expressionism, though its focus later shifted towards abstraction under the influence of artists like his son Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth.

Later, Nicholson was a co-founder of Unit One in 1933, alongside prominent modernists including the sculptor Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth. This short-lived but influential group aimed to unite avant-garde tendencies in British art and architecture, advocating for a "truly contemporary spirit." While Nicholson's own work remained more representational than that of Moore or Hepworth, his involvement signifies his connection to and support for the modern movement in Britain, even as his personal style retained its unique character. His work was also exhibited alongside respected European artists like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Eugène Carrière, and Jozef Israëls, indicating his standing within the broader art world of his time.

Personal Life, Connections, and Recognition

William Nicholson's personal life was intertwined with his artistic career. His first marriage to Mabel Pryde lasted until her death from influenza in 1918. Mabel was herself a painter and connected to artistic circles that included figures like Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris through her family. William and Mabel had four children, including the highly influential abstract painter Ben Nicholson (1894-1982), the artist Nancy Nicholson, and the architect Christopher (Kit) Nicholson. The artistic legacy clearly ran strong within the family.

Following Mabel's death, Nicholson had a relationship with his housekeeper, Marie Laquette, who had cared for Mabel during her illness and subsequently looked after the children. Marie features in some of his paintings. In 1919, Nicholson married Edith Stuart-Wortley, a fellow painter and the widow of Sir John Stuart-Wortley. They had one daughter, Liza. His family life, with its connections to other artists and creative individuals, formed an important backdrop to his career.

Nicholson was known among his peers for his wit, charm, and cultural sophistication. His friendship with figures like Siegfried Sassoon extended beyond mere professional acquaintance. His contributions to British art were formally recognised over time. He served as a Trustee of the Tate Gallery, a prestigious position reflecting his standing in the art establishment. In 1936, he was knighted for his services to art, becoming Sir William Nicholson.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

The later part of William Nicholson's career saw him continue to paint with his characteristic refinement, though his output may have lessened. His health reportedly declined during the Second World War, impacting his ability to work extensively in his final years. He passed away in Blewbury, Berkshire, in 1949, leaving behind a rich and varied body of work.

For a time, particularly during the mid-20th century ascendancy of abstract art, Nicholson's quieter, more representational style was somewhat overshadowed, especially when compared to the international fame achieved by his son, Ben Nicholson. He was sometimes perceived as a talented but essentially conservative figure. However, later reappraisals have increasingly recognised the unique quality and lasting significance of his art. A major retrospective exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 2004 helped to reassert his importance in the narrative of British art.

Influence on Subsequent Art

William Nicholson's influence extends through several channels. His revolutionary work in printmaking and graphic design with the Beggarstaff Brothers set a new standard for poster art and illustration in Britain, demonstrating the power of simplification and bold composition. This graphic sensibility arguably informed his approach to painting as well, evident in the strong design underpinning his canvases.

His mastery of still life and landscape painting provided a touchstone of quality and subtle modernism. While not an avant-garde radical, his sophisticated handling of paint, light, and composition offered an alternative path for artists navigating between tradition and the pressures of modern movements. His ability to find profound beauty in the everyday, rendered with elegance and technical assurance, continues to resonate.

Perhaps his most direct and significant influence was on his son, Ben Nicholson. Ben inherited his father's sensitivity to texture and composition but pushed these elements towards abstraction. Ben Nicholson became a leading figure in British modernism, developing a distinctive style of geometric abstract reliefs and paintings. He maintained connections with major European modernists like Piet Mondrian and Georges Braque, playing a crucial role in linking British art to international developments. While Ben forged his own path, the foundation laid by his father's artistic integrity and technical skill was undoubtedly important.

Beyond his son, William Nicholson's work impacted British art education and offered inspiration to painters who valued craftsmanship, subtlety, and a modern interpretation of representational themes. His dedication to his craft, his unique blend of tradition and innovation, and the sheer quality of his output ensure his place as one of the most respected and influential British artists of the first half of the twentieth century.

Conclusion

Sir William Nicholson was an artist of exceptional talent and versatility. From the groundbreaking graphic designs of the Beggarstaff Brothers to his exquisitely sensitive paintings of still lifes, landscapes, and portraits, he demonstrated a consistent mastery of technique wedded to a unique artistic vision. He successfully navigated the complex artistic landscape of his time, absorbing influences from Impressionism and Post-Impressionism while forging a personal style that resisted easy categorization. Though sometimes overshadowed by the more radical innovations of modernism or the fame of his own son, Nicholson's contribution is undeniable. His work celebrates the beauty of the observed world through sophisticated composition, subtle tonality, and a profound understanding of light. As a printmaker, painter, illustrator, and influential figure within the British art scene, William Nicholson left a legacy of elegance, technical brilliance, and quiet innovation that continues to be admired.