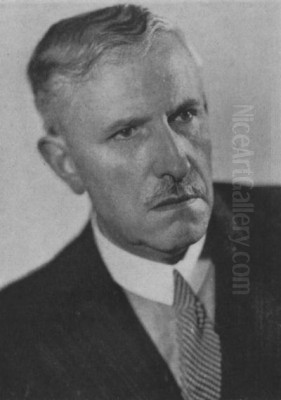

Johannes Hendricus Jurres (1875-1946) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of Dutch art bridging the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A painter celebrated for his profound realism, dramatic compositions, and an uncanny ability to imbue his subjects with palpable life, Jurres carved a distinct niche for himself. His oeuvre, rich with historical, biblical, literary, and everyday scenes, showcases a unique fusion of Dutch artistic traditions with a vibrant, almost theatrical sensibility, partly absorbed from his experiences in Spain. This exploration delves into the life, work, and enduring legacy of an artist who, in his time, was compared to the titans of the Dutch Golden Age and beyond.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Leeuwarden, Netherlands, on January 17, 1875, Johannes Hendricus Jurres embarked on his artistic journey with a clear dedication to the figurative tradition. His formative years as an artist were significantly shaped by his studies at the prestigious Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten (Royal Academy of Fine Arts) in Amsterdam. This institution, a bastion of academic training, provided him with a solid foundation in drawing, painting, and art theory. During his time there, from approximately 1892 to 1897, he would have been immersed in an environment that, while upholding classical principles, was also responding to the burgeoning modern art movements across Europe.

At the Rijksakademie, Jurres studied under influential figures such as August Allebé, a painter known for his genre scenes and portraits, who was also the director of the academy for a significant period. Allebé's emphasis on careful observation and technical skill would have resonated with Jurres's own inclinations. Among his contemporaries at the academy was Félicien Bobeldijk, another Dutch painter who would go on to achieve recognition. The competitive yet collaborative atmosphere of the Rijksakademie undoubtedly played a role in honing Jurres's skills and shaping his artistic vision. Even in his youth, his burgeoning talent was recognized, with some observers noting that his work, though perhaps still developing technically, possessed a certain "ancient glory" that set him apart from many of his peers.

The Development of a Distinctive Style

Jurres's artistic style is characterized by a robust realism, a preference for grand and often dramatic scenes, and an empathetic portrayal of the human condition. He was not an artist of fleeting impressions or abstract explorations; rather, his focus remained steadfastly on the narrative potential of the human figure and its interaction with the environment. His canvases often exude a sense of gravitas, whether depicting a poignant biblical parable, a scene from classic literature, or the unvarnished reality of everyday life.

A notable characteristic of his work is what has been described as a "Dutch haziness" combined with the vibrant "color and light" reminiscent of Spanish art. This suggests a sophisticated understanding of atmospheric perspective and a bold, yet controlled, use of color to enhance the emotional tenor of his scenes. His figures are not mere mannequins but are rendered with a psychological depth that makes them relatable and believable. He possessed a keen eye for capturing the essence of his subjects, conveying their emotions and circumstances through posture, facial expression, and the interplay of light and shadow. This commitment to verisimilitude, coupled with a flair for dramatic composition, became the hallmark of his artistic identity.

Thematic Concerns: From Sacred Texts to Secular Life

The thematic range of Johannes Hendricus Jurres's work is impressively broad, yet consistently anchored by his interest in human drama and storytelling. He drew inspiration from a variety of sources, demonstrating a versatility that allowed him to tackle diverse subjects with equal conviction.

Biblical narratives formed a significant portion of his output. Works such as The Good Samaritan, The Prodigal Son, and Peter and the Cripple are prime examples of his ability to translate these timeless stories into compelling visual statements. In The Prodigal Son, for instance, Jurres masterfully captures the raw emotion of repentance and forgiveness, often using strong contrasts of light and dark to heighten the scene's dramatic impact. His depiction of The Stoning of St. Stephen is noted for its "rougher" style, indicating his willingness to adapt his technique to suit the intensity of the subject matter. These biblical paintings were not simply illustrative; they were profound explorations of faith, morality, and the human spirit.

Literature also provided a rich vein of inspiration for Jurres. He was particularly drawn to the works of Cervantes and Shakespeare. His interpretations of Don Quixote are among his most celebrated pieces, capturing the tragicomic essence of the iconic knight-errant. These paintings often highlight Don Quixote's idealism clashing with harsh reality, rendered with both sympathy and a touch of melancholy. Similarly, his engagement with Shakespearean themes would have allowed him to explore complex characters and dramatic situations, aligning perfectly with his narrative inclinations.

Beyond the sacred and the literary, Jurres also turned his gaze to the realities of contemporary life, particularly the experiences of ordinary people. His depictions of Spanish Beggars, for example, showcase his ability to find dignity and humanity in subjects often overlooked. These works reflect a social awareness and an empathetic eye, characteristics that align him with the broader Realist movement that sought to portray life without idealization. His commitment to "unadorned human figures" is evident in these portrayals, where the focus is on authentic representation rather than romantic embellishment.

The Spanish Sojourn and its Impact

A pivotal period in Jurres's artistic development was his time spent living and studying in Spain. While the exact dates and duration of his stay are not always precisely documented in readily available sources, its influence on his art is undeniable. Spain, with its rich artistic heritage, dramatic landscapes, and vibrant culture, offered Jurres a new palette of colors, a different quality of light, and a wealth of new subjects.

The "Spanish color and light" frequently noted in descriptions of his work directly stems from this experience. The intense sunlight of Spain, so different from the more diffused light of the Netherlands, likely encouraged a bolder use of color and a greater emphasis on contrasts. This can be seen in the warmth of his palettes and the way light models his figures in works inspired by or created during this period. Artists like Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, a Spanish contemporary renowned for his luminous depictions of everyday life under the Mediterranean sun, were mastering this light, and while direct influence is speculative, the Spanish environment itself was a powerful teacher.

Furthermore, his encounters with Spanish culture and its people provided him with fresh thematic material. Scenes of Spanish life, including the aforementioned Spanish Beggars and his Don Quixote series, are imbued with an authenticity that speaks to his direct observation and immersion. The dramatic and passionate character often associated with Spanish culture may also have resonated with Jurres's own penchant for theatricality in his compositions. His time in Spain, therefore, was not merely a geographical relocation but a transformative artistic experience that enriched his style and broadened his thematic horizons.

Notable Works and Artistic Achievements

Several key works stand out in Johannes Hendricus Jurres's oeuvre, each exemplifying different facets of his talent.

Don Quixote: This theme, which he revisited, allowed Jurres to explore pathos, idealism, and the human condition. His depictions are often characterized by a sympathetic portrayal of the deluded knight, emphasizing the nobility of his intentions even amidst his folly. The Spanish landscape often forms a fitting backdrop, rendered with the characteristic warmth and light absorbed during his time there.

The Prodigal Son: A powerful biblical narrative that Jurres rendered with considerable emotional depth. Such works highlight his skill in conveying complex human relationships and spiritual themes through expressive figuration and dramatic lighting, reminiscent of the chiaroscuro employed by masters like Rembrandt van Rijn. The collection of Alfred Henry Lewis reportedly included a version of this painting, praised for its strong light and color contrasts.

Portrait of Marie-Louise Lebrun: While renowned for his narrative scenes, Jurres was also a capable portraitist. This particular work, which fetched a significant price at auction ($280,000, as noted in one source, though auction details can vary), demonstrates his skill in capturing not just a likeness but also the personality of the sitter. His portraits, like his narrative works, benefit from his realistic approach and attention to detail.

Spanish Beggars: This painting, or series of works on this theme, showcases his empathetic portrayal of marginalized figures. It reflects the influence of Spanish Realism and artists like Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, who, centuries earlier, had also depicted similar subjects with dignity. Jurres’s approach is unsentimental yet deeply human.

The Good Samaritan and Peter and the Cripple: These biblical scenes further underscore his commitment to religious themes, rendered with a focus on the narrative and the emotional core of the stories. His ability to stage these scenes effectively, managing multiple figures and conveying a clear message, was a testament to his compositional skills.

His works were generally well-received, and he earned a reputation as a skilled storyteller in paint. The comedian Francis Wilson, an admirer, particularly appreciated Jurres's "expressive but not jarring" works, painted in a "Dutch way," suggesting an appreciation for both his technical skill and his nuanced emotional expression.

Academic Role and Comparisons to Masters

Johannes Hendricus Jurres's standing in the art world of his time was further solidified by his appointment as a professor at the Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten in Amsterdam. This position was a significant honor and indicated the high regard in which he was held by his peers and the art establishment. As a professor, he would have played a crucial role in shaping the next generation of Dutch artists, imparting the principles of academic drawing and painting that he himself had mastered. His own work, with its emphasis on strong narrative, technical proficiency, and emotional depth, would have served as a powerful example for his students.

Perhaps one of the most telling indicators of Jurres's contemporary esteem is the fact that he was often compared to some of the greatest masters in art history, including Rembrandt van Rijn, Diego Velázquez, and Peter Paul Rubens. While such comparisons must be understood within their historical context – often meant to praise a contemporary artist by likening their qualities to revered predecessors rather than suggesting an exact equivalence in overall historical impact – they nonetheless speak volumes about the perceived quality and ambition of Jurres's work.

The comparison to Rembrandt is perhaps the most natural for a Dutch artist known for dramatic, often biblical, scenes with strong chiaroscuro and psychological insight. Velázquez, the Spanish master, would have been an understandable point of reference given Jurres's Spanish sojourn and his realistic, dignified portrayal of figures, including those from everyday life. Rubens, with his dynamic compositions and rich, vibrant colors, might be evoked when considering the more theatrical and grand-scale aspects of Jurres's narrative works. These comparisons highlight Jurres's perceived mastery of technique, his ability to handle complex compositions, and the emotional power of his paintings.

Jurres in the Context of His Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Johannes Hendricus Jurres, it's essential to place him within the artistic currents of his time. The late 19th and early 20th centuries were a period of immense artistic ferment in Europe. While Jurres remained largely committed to a form of narrative realism, he was working in an era that saw the rise of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, Fauvism, and the beginnings of Cubism.

In the Netherlands, artists like George Hendrik Breitner and Isaac Israëls were prominent figures of Amsterdam Impressionism, capturing the bustling city life with a more immediate and sketch-like technique. Jan Toorop was exploring Symbolism and Art Nouveau. Piet Mondrian, a contemporary, was in his early, more representational phase before his journey into pure abstraction. Vincent van Gogh, though his major work predates Jurres's peak, had a posthumous influence that was beginning to spread, championing expressive color and emotional intensity.

Jurres's path was somewhat different. He can be seen as continuing a strong tradition of narrative and historical painting, albeit infused with his own distinct style. He shared with artists like Lawrence Alma-Tadema (also of Dutch origin, though primarily active in Britain) and his Frisian compatriot Christoffel Bisschop a dedication to meticulously rendered scenes, often with historical or genre subjects. Jurres, Bisschop, and Alma-Tadema were indeed considered among the most notable painters from the Friesland region in the late 19th century, achieving international recognition for their storytelling abilities.

While some artists were pushing the boundaries of representation towards abstraction, Jurres found his strength in refining and reinterpreting established genres. His commitment to realism and narrative did not mean his work was anachronistic; rather, it represented a powerful and enduring strand of artistic practice that continued to resonate with audiences and critics. His focus on "grand and dramatic scenes" set him apart from the more intimate focus of some Impressionists, aligning him more with academic traditions, yet his emotional intensity and the "unadorned" nature of his figures gave his work a modern sensibility.

Challenges and Critical Perspectives

Despite his successes, an artist working in a predominantly realist and narrative style during a period of burgeoning modernism might have faced certain challenges. The avant-garde movements were increasingly capturing critical attention, and traditional academic painting was sometimes viewed as conservative. However, Jurres's skill and the compelling nature of his work ensured his continued relevance.

One intriguing, though somewhat cryptic, piece of information suggests that in 1943, Jurres, described as a "history painter," refused a position as "second secretary." The context of this refusal is unclear from the provided snippets, but occurring during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, it could hint at a principled stand or a desire to remain focused on his art during a tumultuous period. This detail, if accurate and pertaining to him, adds another layer to his persona, suggesting integrity beyond his artistic endeavors.

His work was generally praised for its technical execution and narrative power. The assertion that his creations were "more of the ancient glory of Greece and Rome than many other younger artists in modern painting history" suggests that critics saw in his art a timeless quality, a connection to classical ideals of beauty and humanism, even as he depicted scenes from more recent history or everyday life. This "ancient glory" might refer to the dignity he conferred upon his subjects and the seriousness with which he approached his art, qualities often associated with classical traditions.

Other Ventures: The Realm of Music and Design

Beyond his primary focus on painting, Johannes Hendricus Jurres also appears to have engaged in design work connected to the world of music. There is a mention of his involvement in designing an organ case for a Dutch pavilion, possibly for an event like a World's Fair (the Paris World Exposition is mentioned in one context). Another reference links him to providing inspiration for the interior decoration of an organ designed by Flentrop, a renowned Dutch organ builder. This design was intended to "break the mold of traditional Dutch organ building."

Such involvement, though perhaps a smaller part of his career, indicates a breadth of artistic interest and a willingness to apply his aesthetic sensibilities to different media. The design of an organ case, a significant visual component of a musical instrument, would require a strong sense of form, proportion, and ornamentation – skills that a classically trained painter like Jurres would possess. His aim to "break the mold" suggests an innovative spirit, even within a traditional craft.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

Johannes Hendricus Jurres passed away on November 2, 1946, in Amsterdam. He left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be appreciated for its technical mastery, narrative depth, and emotional resonance. While he may not be as universally recognized today as some of his avant-garde contemporaries like Mondrian or Van Gogh, his contribution to Dutch art is significant. He represents a powerful continuation of the realist tradition, infused with a unique blend of Dutch and Spanish influences.

His paintings are held in various public and private collections, and they occasionally appear at auction, where works like the Portrait of Marie-Louise Lebrun can command high prices, attesting to their enduring value. The comparisons made during his lifetime to masters like Rembrandt, Velázquez, and Rubens, while needing careful contextualization, underscore the high esteem in which his talents were held.

Jurres's legacy lies in his ability to tell compelling stories through his art. He captured the drama of biblical events, the romance of literature, and the quiet dignity of everyday life with equal skill and empathy. His figures are not merely painted; they seem to live and breathe on the canvas, inviting viewers to connect with their joys, sorrows, and struggles. In an art world increasingly drawn to abstraction and conceptualism, the work of Johannes Hendricus Jurres stands as a testament to the enduring power of narrative realism and the profound humanism that can be conveyed through the skillful depiction of the human form and experience. He remains a distinguished figure in the rich tapestry of Dutch art, a master storyteller whose canvases continue to speak to us today.