Wu Changshuo stands as a colossus in the landscape of modern Chinese art history. Born Wu Jun and later known as Junqing , he adopted numerous sobriquets including Changshuo, Cangshi , and Kutie , reflecting facets of his life and artistic persona. Hailing from Anji County in Zhejiang Province, Wu Changshuo mastered the "Four Excellences" – poetry, calligraphy, painting, and seal carving – achieving a synthesis that revitalized traditional Chinese art forms at a time of immense societal change. His powerful and distinctive style, deeply rooted in ancient traditions yet boldly innovative, earned him renown as the "First Master of Stone Drum Script" and the "Last Great Peak of Literati Painting," leaving an indelible mark on subsequent generations of artists in China and beyond.

Early Life and the Crucible of Experience

Wu Changshuo was born into a scholarly family with a distinguished lineage; both his grandfather and father had achieved the rank of juren , provincial-level civil service examination graduates. This environment steeped him in Confucian learning and the classical arts from a young age. He began his studies in poetry and calligraphy, laying the foundation for his future artistic pursuits. However, his youth was dramatically interrupted by the turmoil of the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864). The conflict forced his family to flee their home, leading to years of displacement, hardship, and personal loss.

These harrowing experiences profoundly shaped Wu Changshuo's character and artistic vision. The resilience required to survive, the exposure to the raw realities of life and death, and the sense of cultural rupture instilled in him a certain gravitas and a deep connection to the enduring strength he later found in ancient artifacts. This period of wandering and struggle contributed to the rugged, powerful, and sometimes somber tones found in his later work. The "bitter iron" of his sobriquet, Kutie, likely references these formative years of adversity.

Despite the disruptions, Wu continued his classical studies. At the age of 26 (around 1869), he successfully passed the county-level imperial examination, earning the title of xiucai . This achievement could have paved the way for an official career, a traditional path for educated men of his time. However, Wu Changshuo made a pivotal decision to forgo the uncertainties and constraints of officialdom, choosing instead to dedicate his life fully to the pursuit of art. This marked the beginning of his journey as a professional artist, scholar, and poet.

Forging an Artistic Path: Study, Travel, and Connection

Having committed himself to art, Wu Changshuo embarked on a period of intensive study and travel. He journeyed extensively, seeking out knowledge, inspiration, and mentorship. He immersed himself in the study of ancient bronzes and stone steles, particularly the inscriptions, which became a cornerstone of his artistic practice. This focus on epigraphy, known as jinshi xue , was crucial in developing the distinctive "metal and stone" flavor that permeates his calligraphy, painting, and seal carving.

During his travels and studies, primarily in regions like Jiangsu and Shanghai, Wu connected with numerous influential scholars, calligraphers, painters, and collectors. In his early phase, figures like Pan Xitao , Shi Xuchen , the established scholar-official Wu Yun , and the renowned classicist Yu Yue played significant roles. Yu Yue, in particular, served as a mentor, profoundly influencing Wu's understanding of poetry and classical scholarship, which enriched the literary depth of his art. He also associated with painters like Wu Botao and the calligrapher Yang Xian .

His time spent in Suzhou, a major cultural hub, was particularly fruitful. There, his circle expanded to include prominent figures such as the high-ranking official and connoisseur Weng Tonghe , the poet Zhu Xiaozang , the painter Gu Lingshi , the epigrapher and collector Pan Zuyin , and the scholar-official and artist Wu Dacheng . These interactions provided invaluable opportunities for intellectual exchange, exposure to important collections, and mutual artistic stimulation.

Among his most significant relationships during this period was his close friendship with the celebrated painter Ren Bonian , a leading figure of the Shanghai School. They frequently discussed art theory and techniques, and their bond is immortalized in seals Wu carved for Ren, such as "Hua Nu" and "Ren Heshang" , reflecting their shared dedication and camaraderie. This exchange undoubtedly influenced both artists, pushing Wu towards greater expressiveness in his painting.

The Four Excellences: Wu Changshuo's Artistic Universe

Wu Changshuo's enduring fame rests on his exceptional mastery across the four traditional arts of the Chinese literati: painting, calligraphy, seal carving, and poetry. He did not merely excel in each discipline individually; his true genius lay in his ability to integrate them, allowing the principles and aesthetics of one to inform and enrich the others, creating a powerful, unified artistic language.

Painting: The Power of Ink and Brush

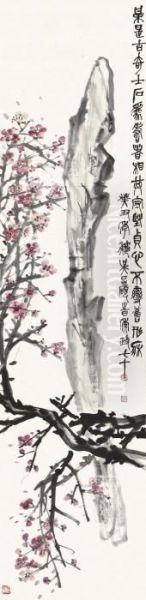

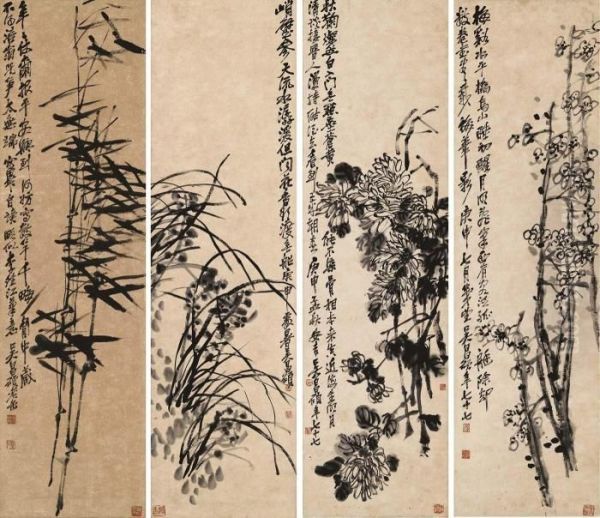

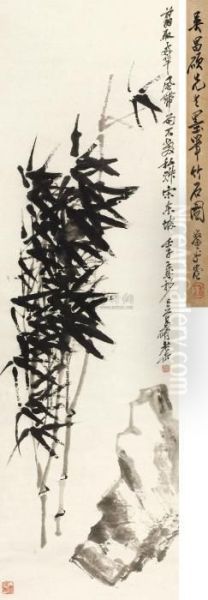

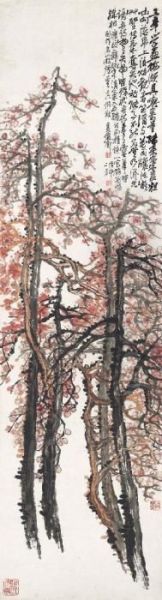

Wu Changshuo is most celebrated for his paintings, particularly his freehand depictions of flowers and plants. He favored subjects imbued with symbolic meaning in Chinese culture, such as plum blossoms (resilience), orchids (elegance), bamboo (integrity), and chrysanthemums (nobility), as well as lotuses, peonies, gourds, and wisteria. His approach was characterized by bold, vigorous brushwork, often described as cangjin hunhou – aged, strong, deep, and resonant.

Rejecting meticulous realism, Wu emphasized capturing the vital spirit and inner life force of his subjects, adhering to the principle of "painting the spirit, not just the form" . His compositions are often dynamic and unconventional , breaking free from staid arrangements. He applied ink with confidence, using rich, dark tones alongside more nuanced washes, achieving both strength and subtlety.

A distinctive feature of his painting is the integration of calligraphic techniques, particularly the powerful lines derived from seal script. He famously employed the "methods of zhuan and zhou" – referring to ancient seal script styles – in his brushwork, giving his painted lines a weighty, sculptural quality reminiscent of carved inscriptions. This infusion of jinshi aesthetics set his work apart. Furthermore, Wu was known for his bold use of color . He skillfully incorporated vibrant hues, notably a bright Western red , alongside traditional pigments, creating visually striking contrasts without sacrificing scholarly elegance.

Representative masterpieces showcase these qualities. His Mo He Tu paintings utilize the robust lines of seal script to depict the structure and energy of lotus leaves and stems, with ink tones ranging from deep black to translucent grey. The Mo Mei Tu Zhou exemplifies his mastery of the plum blossom theme, with gnarled branches rendered in forceful, "iron-wire" lines and blossoms dashed in with expressive dots of ink or color. Works like Siji Huahui Siping demonstrate his ability to handle complex compositions and varied subjects, while Guishou Shenxian Tu highlights his skill in figure painting, often incorporating auspicious themes with rich coloration and lively brushwork.

Calligraphy: Echoes of Ancient Stone

Calligraphy formed the bedrock of Wu Changshuo's art. While proficient in various scripts, he achieved unparalleled mastery in seal script . His primary inspiration came from the ancient inscriptions on the Stone Drums of Qin , dating back perhaps to the Eastern Zhou dynasty or early Qin dynasty. He studied these archaic characters relentlessly, internalizing their structure, strength, and primitive simplicity. His dedication earned him the accolade "First Master of Stone Drum Script."

Beyond the Stone Drums, Wu drew heavily from Han dynasty steles and bronze inscriptions. He synthesized these ancient sources, developing a personal style characterized by its pumao xiongjian quality – simple, flourishing, vigorous, and robust. His seal script possesses a sense of archaic grandeur, structural integrity, and dynamic energy. The lines are often thick and powerful, yet retain a sense of fluidity and rhythm.

He frequently incorporated his calligraphy directly into his paintings as inscriptions, which were not mere additions but integral parts of the overall composition, balancing the visual elements and adding layers of literary meaning. His mastery of calligraphy, especially seal script, provided the fundamental linear strength that defines his painting and seal carving.

Seal Carving: The Blade's Ancient Voice

Seal carving was Wu Changshuo's earliest artistic focus, and he remained a dominant figure in the field throughout his life. He approached seal carving with the same scholarly rigor and innovative spirit as his other arts. His primary models were the seals of the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) and the rough, unadorned impressions left by ancient clay seals .

From these sources, he forged a distinctive style often described as gaogu – lofty and ancient. His seals possess a powerful, unrefined aesthetic, emphasizing the natural texture of the stone and the decisive cuts of the carving knife. He masterfully manipulated the ancient seal script characters within the confined space of the seal face, achieving compositions that were both balanced and dynamic, often with a deliberate asymmetry or an appearance of weathered antiquity.

Wu Changshuo was considered a pioneer who revitalized the art of seal carving in the late Qing period. He broke away from the overly meticulous and decorative trends that had become prevalent, returning to the robust spirit of ancient models while infusing them with his own powerful artistic personality. His seals are highly prized not only for their technical brilliance and aesthetic appeal but also as miniature expressions of his overall artistic philosophy, embodying the jinshi spirit in its purest form.

Poetry: The Literati's Heart

While perhaps less widely known internationally than his visual arts, Wu Changshuo was also an accomplished poet. His poems often reflect his personal experiences, his observations of nature, his appreciation for antiques, and his thoughts on art and life. They frequently carry patriotic sentiments and a sense of historical consciousness, particularly reflecting the turbulent times he lived through.

His poetry is deeply intertwined with his painting and calligraphy. He frequently inscribed his own poems onto his artworks, creating a dialogue between image, text, and calligraphy. This practice aligns with the highest ideals of literati art, where the artist expresses a complete intellectual and emotional world through the seamless integration of multiple art forms. Collections of his manuscripts, such as the Canlu Shihanyizhen , offer glimpses into his literary mind and calligraphic skill in a more intimate format.

The Shanghai Years and the Xiling Seal Society

In his later years, Wu Changshuo settled in Shanghai, the bustling metropolis that had become the vibrant center of Chinese art and commerce. He became a leading figure in the city's dynamic art scene, associated with the flourishing Shanghai School of painting, known for its blend of tradition and modernity, and its appeal to a new urban clientele.

A testament to his stature in the art world was his election in 1913 as the first president of the prestigious Xiling Seal Society , located in Hangzhou by the West Lake. This society, dedicated to the study and practice of seal carving and epigraphy, brought together leading artists and scholars. Wu's leadership cemented its importance as a major institution for the preservation and development of traditional arts.

Even in his advanced years, Wu remained remarkably productive, continuing to paint, carve seals, practice calligraphy, and write poetry. He actively participated in artistic gatherings and mentored younger artists. His Shanghai studio became a hub for artists and collectors. During this period, his friendships with figures like the influential painter and businessman Wang Yiting were crucial. Wang Yiting not only supported Wu personally but also played a key role in promoting his work, particularly to Japanese collectors. Other close associates in these later years included scholars and artists like Chen Shenli , Zeng Shenzhi , Li Ruiqing , and the poet Zhu Zongyuan , with whom he frequently exchanged poems.

Network and Influence: Contemporaries and Successors

Wu Changshuo's long life and extensive travels placed him at the center of a vast network of artistic and scholarly relationships. His interactions spanned generations and geographical regions, reflecting his broad influence and respected position within the late Qing and early Republican art worlds. His early mentors like Yu Yue, mid-career collaborators like Ren Bonian and Wu Yun, and later associates like Wang Yiting all contributed to his development and reach.

His impact extended significantly to the next generation of artists. He directly taught or mentored several important figures who carried forward aspects of his legacy. Among his notable disciples were Zhu Wenyun and Zhu Lesan , who became respected painters and educators, and Chen Shizeng , a highly influential painter, critic, and art theorist who played a key role in promoting traditional painting in Beijing. Wang Yiting, though also a contemporary and collaborator, can be seen as someone who learned from and promoted Wu's art.

Beyond his direct students, Wu Changshuo's powerful "metal and stone" aesthetic and his revitalization of xieyi painting profoundly influenced many major artists of the 20th century. Qi Baishi , who famously transitioned to a bolder style later in life, acknowledged Wu's impact, particularly his integration of seal carving principles into painting and calligraphy. Pan Tianshou , another giant of modern Chinese painting known for his strong compositions and unique style, clearly absorbed lessons from Wu's structural power and brushwork. Even Huang Binhong , renowned for his dense, layered ink landscapes, shared Wu's deep engagement with ancient traditions and vigorous brushwork, reflecting the broader artistic currents Wu helped shape. His association with figures like Zhang Boying and Lu Yifei further illustrates the breadth of his connections.

Wu Changshuo is rightly considered a pivotal figure who bridged the gap between the late imperial literati tradition and the emerging modern art scene of the 20th century. He reinvigorated traditional forms, infused them with personal strength and contemporary relevance, and provided a powerful model for subsequent artists seeking to navigate the complexities of tradition and innovation in a rapidly changing China.

International Recognition: Japan and Beyond

While firmly rooted in Chinese tradition, Wu Changshuo's art achieved significant recognition beyond China's borders, particularly in Japan. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was considerable cultural exchange between Chinese and Japanese artists and scholars. Wu's work, with its powerful brushwork, archaic flavor derived from epigraphy, and vibrant colors, resonated strongly with Japanese aesthetic sensibilities.

Figures like Wang Yiting actively promoted Wu's art in Japan, facilitating connections and sales. Japanese artists and collectors, such as Kawai Senro and Nagao Ko , held Wu Changshuo in high esteem. They visited him in Shanghai, corresponded with him, and avidly collected his paintings, calligraphy, and seals. Consequently, a large number of Wu Changshuo's works found their way into Japanese collections, both public and private, where they remain highly valued today. His influence extended to Japanese painting and calligraphy circles of the time.

Wu Changshuo's art also gained exposure in the West, albeit later. His work was included in exhibitions aiming to introduce modern Chinese art to international audiences. For instance, his paintings were featured in shows like the "Five Outstanding Modern Chinese Painters" exhibition that traveled to the United Kingdom and the United States. Such events helped to foster a greater appreciation and scholarly interest in modern Chinese art history in the West, positioning Wu Changshuo as a key representative of the era's artistic achievements. He thus served as an important cultural bridge, demonstrating the enduring power and adaptability of Chinese artistic traditions on a global stage.

Character and Anecdotes

Beyond his artistic achievements, accounts of Wu Changshuo's life reveal a personality marked by integrity, resilience, humility, and occasional eccentricity. He was known for his indifference to fame and fortune, maintaining a relatively simple lifestyle even when his art commanded high prices. His patriotism was evident in actions like his efforts during the early Republican era to help preserve the Han Sanlao Hui Zi Ji Ri Bei , an important Han dynasty stele, from falling into foreign hands.

Anecdotes offer glimpses into his character. His deep connection with nature and art is shown in the story of his visit to Chaoshan near Hangzhou, famous for its plum blossoms, where he spontaneously struck up a friendship with the reclusive Lao family. His empathy and perhaps melancholic awareness of life's hardships are suggested by the seal "Tianxia Shangxin Nanzi" he carved for his friend Wu Shoulü , commemorating a life dedicated to art but marked by personal loss.

A touch of humor appears in the tale involving his disciple Wang Geqi . While walking one evening, Wu complained of a headache, pointing towards a figure seemingly praying. Wang Geqi discovered an elderly woman bowing devoutly to a bronze bust of Wu Changshuo, mistaking it for a Buddhist idol. This incident highlights both Wu's local fame and his down-to-earth reaction.

His later life was not without hardship. A serious car accident caused facial injuries and considerable pain, requiring a long period of convalescence. Yet, he maintained his dedication to art. His love for collecting antique stones was well-known, sometimes leading to amusing situations, like the incident where a fan painter by Ping Jinya was mistakenly sold but later returned, prompting Wu to host a banquet and paint a scroll in gratitude. He was known for his sincerity in friendships and his eagerness to learn throughout his life, advocating for artistic independence and innovation over slavish imitation of past masters.

Legacy and Scholarly Attention

Wu Changshuo passed away in Shanghai in 1927 at the age of 84, likely due to complications following a stroke. He left behind a monumental artistic legacy that continues to resonate deeply within Chinese art history. As a master of the "Four Excellences," he demonstrated the enduring vitality of the literati tradition while simultaneously forging a bold, modern artistic identity. His powerful jinshi style provided a crucial link between ancient epigraphy and modern painting, offering a path for artists seeking to root innovation in cultural tradition.

His influence on subsequent generations, including giants like Qi Baishi and Pan Tianshou, solidified his position as a foundational figure in 20th-century Chinese art. The Shanghai School, of which he was a leading light, played a critical role in shaping the direction of art in modern China. His role as the first president of the Xiling Seal Society underscored his importance in the preservation and promotion of traditional arts.

In the decades since his death, Wu Changshuo has been the subject of continuous scholarly attention and public appreciation. Numerous exhibitions have been dedicated to his work, both in China and internationally. The Wu Changshuo Memorial Hall in Shanghai and other institutions preserve and display his art and related documents. Academic research continues to explore various facets of his life and work.

Significant publications have consolidated knowledge about him. The monumental Complete Works of Wu Changshuo , published in 2017 in twelve volumes, compiled nearly 5,100 works across all media, including a vital volume of documents (letters, manuscripts, colophons), providing an invaluable resource for researchers. More recent publications, like the revised edition of Wu Changshuo (2024), incorporate contemporary scholarly perspectives from leading experts like Han Tianheng and Tong Yanfang. Studies delve into specific areas like his calligraphy's relationship with the Stone Drum script, the thematic and stylistic evolution of his flower paintings, his seal carving philosophy, and even statistical analyses of his use of different sobriquets over time. Reference works like the Chronological Biography of Wu Changshuo provide detailed life histories.

Conclusion: An Enduring Legacy

Wu Changshuo remains a towering figure whose life and art encapsulate the dynamic transition of Chinese culture from the late imperial era to the modern age. Facing personal hardship and immense societal upheaval, he forged an artistic path defined by profound respect for tradition, relentless self-cultivation, and bold innovation. By masterfully integrating poetry, calligraphy, painting, and seal carving, he revitalized the literati ideal, infusing it with the raw power and archaic resonance of ancient metal and stone inscriptions. His distinctive jinshi style created a new aesthetic paradigm within Chinese painting, influencing generations of artists and securing his place as a key figure in the Shanghai School and modern Chinese art history. Both a preserver of tradition and a daring innovator, Wu Changshuo's legacy endures in his powerful artworks and his lasting impact on the trajectory of art in China and beyond.