Zhang Shanzi, a name that resonates with the raw power of the wild and the fervent spirit of patriotism, stands as a monumental figure in the annals of modern Chinese art. Born at a time of immense societal and political upheaval, his life and art became inextricably linked with the destiny of his nation. Renowned primarily as a master painter of tigers, Zhang Shanzi was more than just an animalier; he was a revolutionary, a scholar, an educator, and a cultural ambassador whose brushstrokes captured not only the essence of the "king of beasts" but also the indomitable spirit of the Chinese people during one of their most trying periods.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Zhang Shanzi, originally named Zhang ZhengLan, with the style name Ze, was born on July 12, 1882, in Neijiang, Sichuan province, into a family with a strong scholarly and artistic tradition. He was the second elder brother of Zhang Daqian, who would himself become one of the most celebrated and versatile Chinese artists of the 20th century. This familial environment undoubtedly nurtured his early artistic inclinations. His first teacher was his mother, who instilled in him a foundational understanding of painting.

As he matured, Zhang Shanzi sought more formal instruction, studying under prominent artists and scholars of the time. Among his most influential mentors were Li Ruiqing , a distinguished calligrapher, painter, and educator, and Zeng Xi , another leading figure in calligraphy and painting, known for his adherence to traditional principles while also embracing innovation. These masters provided Zhang with a rigorous grounding in classical Chinese art forms, techniques, and aesthetics. His artistic pursuits led him to specialize in landscapes, floral subjects, and particularly, animals, with the tiger becoming his most iconic subject.

Beyond his artistic education in China, Zhang Shanzi also experienced the currents of change sweeping across Asia by studying in Japan. This period abroad broadened his horizons and exposed him to different artistic influences and socio-political ideas. It was during this time that his patriotic fervor began to take concrete shape, leading him to join the Tongmenghui, Sun Yat-sen's revolutionary alliance aimed at overthrowing the Qing Dynasty and establishing a republic.

From Public Service to Artistic Dedication

Upon his return to China, Zhang Shanzi's commitment to his country led him into public service and military roles. He participated actively in revolutionary movements, including those opposing Yuan Shikai's attempts to restore the monarchy. His career saw him hold significant positions, such as Major General Brigade Commander, a County Magistrate, and a consultant to the Ministry of Finance. These roles offered him a firsthand view of the complexities and challenges facing China.

However, the pervasive corruption and inefficiencies within the officialdom of the time grew increasingly disillusioning for a man of his principles. By 1926, Zhang Shanzi made a pivotal decision: he resigned from all his official posts to dedicate himself entirely to the pursuit of art. This was not an abandonment of his patriotic ideals but rather a shift in the means by which he sought to serve his country. He believed that art could be a powerful tool for cultural rejuvenation and national inspiration.

Together with his immensely talented younger brother, Zhang Daqian, he co-founded the "Dafeng Tang" (Hall of the Great Wind) studio and artistic school. The name itself, referencing a Han Dynasty song about a great wind rising, symbolized their lofty artistic ambitions and their desire to invigorate Chinese painting. The Dafeng Tang school would become a significant force in modern Chinese art, attracting numerous students and fostering a style that, while rooted in tradition, was open to individual expression and innovation.

The "Tiger Master" and His Unique Approach

Zhang Shanzi's fame became inextricably linked with his extraordinary depictions of tigers. He earned numerous sobriquets reflecting this specialization, including "Huchi" , "Hugong" (Tiger Duke), and "Huzhi" (Tiger Sage). His passion for tigers went beyond mere artistic representation; it was a deep, almost spiritual connection.

To truly understand his subjects, Zhang Shanzi famously undertook the extraordinary step of raising tigers. He kept these majestic animals, most notably at the renowned Master of the Nets Garden (Wangshi Yuan) in Suzhou, a classical Chinese garden that provided an inspiring backdrop. He would spend countless hours observing their movements, their anatomy, their expressions, and their behaviors – from their ferocious roars to their moments of quiet repose or even tenderness. He reportedly even "tamed" them to a degree, allowing him to study them up close, sketching them from life to capture their every nuance. This dedication to direct observation was a hallmark of his practice and contributed significantly to the vitality and accuracy of his tiger paintings.

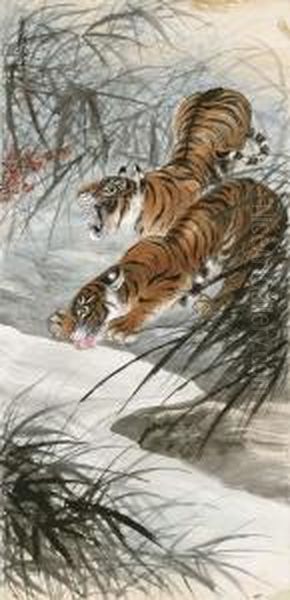

His artistic style, particularly in his tiger paintings, is often described as embodying "Da Xiong Wang Feng" – a "grand and heroic kingly style." This refers to the majestic power, noble bearing, and untamed spirit that he imbued in his tigers. He masterfully combined meticulous detail with expressive brushwork, paying close attention to anatomical accuracy while simultaneously capturing the tiger's qi (vital energy) and shen (spirit). His compositions were dynamic, his use of ink and color rich and evocative, always aiming for a harmonious balance between form and spirit (xing shen jian bei).

Masterpieces and Signature Works

Zhang Shanzi's oeuvre is rich with memorable works, many of which feature his beloved tigers. Among his most celebrated pieces is Fuhu Luohan (Taming the Tiger Arhat). This painting, often considered one of his peak achievements, depicts a Buddhist Arhat calmly subduing a powerful tiger, a traditional theme symbolizing spiritual mastery over primal forces. Zhang's rendition is notable for the serene power of the Arhat contrasted with the formidable yet ultimately deferential tiger, showcasing his ability to convey complex psychological and spiritual narratives.

Other significant works include Shuanghu Tu (Two Tigers), which often explored the dynamic interactions between these animals, and Qunhu Tu (Herd of Tigers), ambitious compositions that showcased his ability to handle multiple figures and create a sense of collective energy and wild majesty. Menghu Pori Tu (Fierce Tiger Pouncing on the Sun) is another powerful image, laden with symbolic meaning, suggesting courage and an indomitable will.

His Shi'er Jinchai Tu (Twelve Golden Hairpins) series is particularly interesting. While "Golden Hairpins" typically refers to beautiful women in Chinese literature, Zhang Shanzi often incorporated tigers into these compositions, perhaps as guardians, symbols of power, or to create a striking juxtaposition of human beauty and wild nature. These works were popular and published multiple times.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, his art took on an explicitly patriotic and propagandistic role. Works like Nuhou ba, Zhongguo! (Roar, China!) used the image of a roaring tiger to symbolize China's defiance and resistance against Japanese aggression. Another iconic piece from this period is the Feihu Tu (Flying Tiger Painting), which he created and gifted to the American Volunteer Group (AVG), famously known as the "Flying Tigers," who aided China in its fight against Japan. This painting became a powerful symbol of Sino-American cooperation and friendship during the war.

A Patriot's Brush: Art in Service of the Nation

The outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 galvanized Zhang Shanzi. He channeled his artistic talents and reputation into the war effort with unwavering dedication. His tiger paintings, already symbols of strength and courage, became potent metaphors for China's will to resist. He believed that art had a crucial role to play in boosting national morale and rallying support for the cause.

Zhang Shanzi embarked on extensive travels, both within China and internationally, to promote the anti-Japanese cause and raise funds. He organized numerous charity art exhibitions, selling his works to contribute to war relief. One of his most significant endeavors was his journey to the United States and Europe. In America, he held exhibitions in various cities, captivating audiences with his powerful art and his passionate advocacy for China. His efforts were remarkably successful, reportedly raising over 200,000 US dollars – a substantial sum at the time – all of which was donated to the Chinese war effort.

His international exhibitions not only raised crucial funds but also helped to garner international sympathy and support for China's plight. He was hailed in the West as a "Representative of Modern Oriental Art," and his dignified presence and compelling art left a lasting impression. His painting The Flying Tiger, presented to General Claire Lee Chennault's Flying Tigers, cemented an enduring image of courage and alliance. This period underscored his belief that an artist's responsibility extended beyond the studio, especially in times of national crisis.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Zhang Shanzi's artistic journey was interwoven with the vibrant and dynamic art scene of Republican China. His closest artistic bond was undoubtedly with his younger brother, Zhang Daqian. While Shanzi was the elder and an early guide for Daqian, Daqian's prodigious talent soon blossomed, and they became artistic peers, co-founding the Dafeng Tang school. Their relationship was one of mutual respect and support, often collaborating or providing critiques for each other. Zhang Shanzi's focus on tigers complemented Zhang Daqian's broader versatility in landscapes, figures, and meticulous copies of ancient masterpieces.

Another key contemporary often discussed in relation to Zhang Shanzi is Xu Beihong. Both were towering figures of their time, deeply patriotic, and known for their mastery in depicting animals – Zhang Shanzi with tigers and Xu Beihong with horses. Xu Beihong, who had studied extensively in Europe, championed realism and the integration of Western techniques to revitalize Chinese painting. While their approaches and primary subjects differed, both artists used their animal depictions to convey national spirit and resilience. For instance, Xu Beihong's galloping horses became symbols of China's unyielding energy, much like Zhang Shanzi's tigers embodied its fierce determination. There was likely a degree of artistic rivalry, as is common among leading figures, but also mutual respect for their shared commitment to art and country.

Beyond these two, Zhang Shanzi's world included many other notable artists. His teachers, Li Ruiqing and Zeng Xi, were highly respected figures. He was also involved in artistic societies, such as the Lanman She , which he co-organized with figures like the landscape master Huang Binhong. Huang Binhong, known for his dense, dark, and powerful landscapes, represented a different but equally vital strand of modern Chinese painting that emphasized the expressive potential of ink.

The early to mid-20th century in China was a period of intense artistic debate and experimentation. Artists like Qi Baishi, with his charming depictions of everyday subjects and creatures executed with calligraphic verve, and Pu Ru (Pu Xinyu), a Manchu prince renowned for his traditional literati painting, represented strong continuations of classical styles. Simultaneously, innovators like Lin Fengmian and Liu Haisu, who both had significant exposure to Western art, were forging new paths by synthesizing Chinese and Western aesthetics. Gao Qifeng and Gao Jianfu, founders of the Lingnan School, were also notable for their attempts to modernize Chinese painting, often incorporating elements of Japanese Nihonga and Western realism, and they too excelled in animal painting, offering a different stylistic approach to fauna compared to Zhang Shanzi. Other prominent artists of the era included Fu Baoshi, known for his evocative landscapes and figures, and Pan Tianshou, who created powerful and often monumental compositions of flowers, birds, and landscapes with a distinctive angularity. Wu Changshuo, though of an earlier generation, cast a long shadow with his bold, epigraphic style in painting and calligraphy, influencing many who came after. Chen Shuren, another key figure of the Lingnan School, also contributed to the diverse artistic landscape. Zhang Shanzi navigated this complex environment, carving out his unique niche while contributing to the broader discourse on the future of Chinese art.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Zhang Shanzi's life was tragically cut short. The immense strain of his wartime efforts, coupled with his relentless dedication to his art, took a toll on his health. He passed away from illness on October 20, 1940, in Chongqing, China's wartime capital, at the age of 59 (by Chinese reckoning, 58 by Western). His death was a significant loss to the Chinese art world and the nation he had served so devotedly. The Nationalist government recognized his contributions with high honors.

His legacy, however, endures. As a painter, he elevated the depiction of the tiger in Chinese art to new heights, imbuing it with unprecedented vitality, psychological depth, and symbolic resonance. His meticulous observation, combined with his expressive brushwork, set a standard for animal painting. The Dafeng Tang school, which he co-founded, continued to be an influential artistic lineage, primarily through the global fame of his brother Zhang Daqian and their many students.

Zhang Shanzi's patriotic actions also form a crucial part of his legacy. He exemplified the artist as a socially responsible citizen, using his talents not just for personal expression or aesthetic pursuits but as a powerful tool for national salvation and cultural diplomacy. His story continues to inspire, demonstrating how art can intersect with history and contribute to a nation's narrative.

Exhibitions and Continued Scholarly Interest

Zhang Shanzi's works continue to be exhibited and studied, attesting to his lasting importance. In recent years, several exhibitions have featured his art:

A 2023 exhibition in Tianjin at the Zhang Shanzi Zhang Daqian Cultural Arts Center commemorated Zhang Daqian but also naturally included the legacy of his elder brother and co-founder of their school.

The Jiangjin Museum held a "Tiger Year" special exhibition in 2020 (and likely again in 2022, the next Tiger year), showcasing works like his Seated Tiger, Color on Paper, Central Hall and Fierce Tiger Scroll.

A "Dafeng Tang Three Generations" exhibition in Hangzhou in 2018 highlighted the continuity of the artistic tradition he helped establish.

His works have been part of broader Chinese painting exhibitions, such as one in Guangzhou in 2017.

Significantly, his wartime painting Roar, China! was exhibited at the Taipei Palace Museum in 2016, underscoring its historical and artistic value.

His art also appears in publications and auctions. The Twelve Golden Hairpins series, for example, was published multiple times during the Republican era and was featured in a centennial commemorative exhibition for him at the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall in Taipei in 1981.

Scholarly interest in Zhang Shanzi remains active. For instance, Neijiang Normal University, located in his home region, has undertaken a key research project titled "A Critical Biography of the Great Patriot Painter Zhang Shanzi," aiming to comprehensively study his art and patriotic spirit. Institutions like the Tsinghua University Art Museum also continue to include his works in exhibitions exploring modern Chinese art.

Conclusion: The Roar That Echoes Still

Zhang Shanzi was a remarkable artist whose life and work were forged in the crucible of a transformative era for China. He was a master of his craft, bringing the tiger to life on paper with unparalleled skill and empathy. But he was also a man of profound conviction, whose patriotism burned as fiercely as the eyes of the tigers he painted. His art was not merely an aesthetic pursuit but a declaration of cultural pride, a call for national resilience, and a bridge to the wider world. From the quiet intensity of his studio observations to the passionate advocacy of his wartime fundraising tours, Zhang Shanzi dedicated his life to his art and his country. The roar of his tigers, symbolic of China's enduring strength, continues to echo in the galleries of Chinese art history, a testament to a life lived with purpose and passion.