The Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) in China was a period of profound cultural and artistic transformation. While Mongol rule brought significant political and social changes, it also fostered an environment where traditional Chinese arts, particularly painting, evolved in new and expressive directions. Among the luminaries of this era, Wu Zhen stands out as a figure of quiet intensity and profound artistic integrity. Born in 1280 in Jiaxing, Zhejiang province, and passing away in 1354, Wu Zhen, also known by his courtesy name Zhonggui and his sobriquets Meihua Daoren and Meisha Shusheng , carved a unique niche for himself. He is celebrated as one of the "Four Masters of the Yuan Dynasty," a group that also includes Huang Gongwang, Ni Zan, and Wang Meng, each of whom left an indelible mark on the landscape of Chinese art.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations in a Tumultuous Era

Wu Zhen's life unfolded against the backdrop of foreign rule. The Southern Song Dynasty had fallen to the Mongol invaders, and many Han Chinese scholar-officials found themselves displaced or unwilling to serve the new regime. This societal shift led many intellectuals to retreat from public life, channeling their energies into personal cultivation through poetry, calligraphy, and painting. Wu Zhen epitomized this spirit of reclusion. While the provided text mentions his grandfather was Zhao Mengfu, this is a significant art historical inaccuracy; Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322) was an older contemporary and a towering figure whose artistic principles greatly influenced the Yuan literati, including Wu Zhen, but they were not related in that manner. Wu Zhen deeply admired Zhao Mengfu's efforts to revive antique styles, particularly those of the Tang and Northern Song dynasties, and this reverence for the past would inform his own artistic journey.

Details about Wu Zhen's early training are scarce, as is common for many artists of his time who were not part of an imperial academy. However, it is evident that he was a learned man, proficient in poetry and calligraphy, skills considered essential for a literati painter. He was also said to be interested in swordsmanship in his youth and later studied Chan (Zen) Buddhism and Daoist philosophy, which profoundly shaped his worldview and artistic expression. He chose a life of simplicity, reportedly making a living by practicing divination and selling his paintings, often frequenting the areas around Jiaxing and Hangzhou. This detachment from worldly ambition allowed him the freedom to pursue his art with uncompromising purity.

The Plum Blossom Daoist: A Life of Principled Reclusion

Wu Zhen’s sobriquet, "Meihua Daoren" or "Plum Blossom Daoist/Monk," reflects his deep affinity for the plum blossom, a symbol of resilience, purity, and perseverance in the face of adversity – qualities highly valued by scholars during the Yuan period. He cultivated plum trees around his modest dwelling, which came to be known as the Meihua An . This hermitage became his sanctuary, a place where he could immerse himself in nature, poetry, calligraphy, and painting, far from the political turmoil and social pressures of the Mongol court.

His reclusive lifestyle was not one of bitter isolation but rather a conscious choice, reflecting a lofty and independent spirit. He was known for his high moral character and his refusal to compromise his principles for fame or fortune. This integrity is palpable in his art, which eschews ostentation in favor of understated strength and profound emotional depth. He found companionship and intellectual stimulation in his interactions with Buddhist monks, such as the monk Xingsong from the Wei Tang area, with whom he would discuss scriptures, compose poetry, and create art. This spiritual dimension is an integral part of understanding Wu Zhen's artistic motivations and the serene, contemplative quality of his work.

Artistic Style: The Somber Power of Ink

Wu Zhen's artistic style is characterized by its somber, moist, and densely textured quality, often described as "cangyu chenhou" – lush, dense, and profoundly heavy or substantial. He was a master of ink, exploiting its full range from the palest washes to the deepest, richest blacks. His brushwork is typically robust and unpretentious, conveying a sense of earthy solidity and inner strength. While he learned from earlier masters, he forged a distinctly personal style that set him apart from his contemporaries.

He drew inspiration from the monumental landscape traditions of the Five Dynasties and Northern Song periods, particularly from masters like Dong Yuan and Juran , whose rounded, "hemp-fiber" texture strokes and emphasis on the naturalistic depiction of southern China's moist, rolling landscapes resonated with him. He also studied the works of Jing Hao and Guan Tong from the Five Dynasties, known for their powerful, architectonic mountain forms. However, Wu Zhen reinterpreted these ancient traditions through the lens of Yuan literati aesthetics, infusing his landscapes with a greater sense of personal expression and calligraphic energy. Unlike the more intricate and detailed styles of some court painters or even some of his fellow literati, Wu Zhen's approach was often broader and more gestural, emphasizing the spirit and inner reality of the landscape rather than mere outward resemblance.

Signature Themes: Fishermen, Bamboo, and Secluded Landscapes

Wu Zhen is particularly renowned for his depictions of fishermen, bamboo, and secluded landscapes, themes that allowed him to explore his philosophical and aesthetic concerns.

Fishermen Scenes: The theme of the fisherman, often depicted alone in a small boat amidst vast waters and misty mountains, was a popular motif in Chinese painting, symbolizing a life of freedom, detachment from worldly cares, and harmony with nature. Wu Zhen's fisherman paintings, such as his numerous scrolls titled Fisherman or Fishermen, after Jing Hao, are not merely idyllic scenes but often carry a melancholic or introspective mood. The figures are small, almost absorbed by the immensity of their surroundings, evoking a sense of solitude and the transient nature of human existence. His use of dark, wet ink and broad, powerful strokes creates an atmosphere of dampness and quietude, perfectly capturing the essence of the watery regions of southern China.

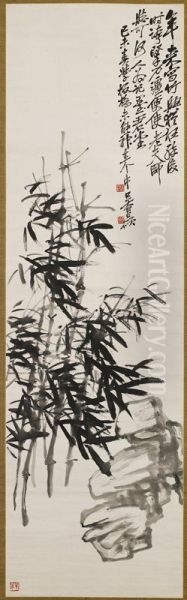

Ink Bamboo: Wu Zhen was an undisputed master of ink bamboo painting, a genre highly esteemed by literati artists for its symbolic associations with integrity, resilience, and the gentleman-scholar . Bamboo, which bends in the wind but does not break, was seen as a metaphor for the scholar who maintains his principles even in times of adversity. Wu Zhen's bamboo paintings, such as his celebrated handscroll Manual of Ink Bamboo , demonstrate his exceptional control of ink tones and brushwork. He could convey the crispness of the leaves, the strength of the stalks, and the very spirit of the plant with remarkable economy and vitality. His bamboo paintings often include his own calligraphy, integrating poetry and image into a unified artistic statement, following the tradition of earlier bamboo masters like Wen Tong and Su Shi of the Song Dynasty.

Landscapes: His pure landscape paintings often depict secluded valleys, rustic dwellings, and towering mountains shrouded in mist. These scenes are imbued with a sense of timelessness and a deep connection to the natural world. Works like Twin Junipers or Central Mountain showcase his characteristic use of dense, moist ink and powerful, textured brushstrokes to build up forms that are both substantial and atmospheric. He often favored a somber palette, relying on the subtle gradations of ink to create depth and mood, rather than vibrant colors. This approach aligns with the literati preference for understated expression and the intrinsic beauty of the ink medium itself.

Representative Works: A Legacy in Ink

While the initial information provided incorrectly attributed Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains to Wu Zhen (it is famously by Huang Gongwang), Wu Zhen has a significant corpus of authentic and celebrated works. Among his most important extant pieces are:

Fishermen : Several versions exist, including a notable handscroll in the Shanghai Museum and hanging scrolls in various collections. These works exemplify his mastery of the fisherman theme, characterized by their atmospheric ink washes and evocative portrayal of solitary figures in nature. One version, often titled Fishermen, after Jing Hao, shows his engagement with earlier masters while asserting his own style.

Manual of Ink Bamboo : Housed in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, this handscroll is a tour-de-force of ink bamboo painting. It presents various studies of bamboo in different weather conditions and from different perspectives, each accompanied by Wu Zhen's calligraphy. It serves almost as a didactic manual, showcasing the versatility of his brush and the depth of his understanding of the subject.

Twin Junipers : Also in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, this powerful hanging scroll depicts two ancient, gnarled juniper trees, symbolizing endurance and strength. The robust, textured brushwork and dark, forceful ink convey the rugged vitality of the trees.

Central Mountain : This work, often cited for its dense composition and powerful brushwork, captures the monumentality of nature and the artist's profound connection to it.

Poetic Feeling in a Thatched Pavilion : This painting showcases a scholar in a rustic pavilion, a common literati theme, rendered with Wu Zhen's characteristic somber tones and expressive brushwork, emphasizing the contemplative mood.

These works, among others, demonstrate Wu Zhen's unique artistic vision and his significant contributions to the development of literati painting in the Yuan Dynasty.

Wu Zhen and the "Four Masters of the Yuan Dynasty"

Wu Zhen's place among the "Four Masters of the Yuan Dynasty" is secure, yet his style offers a distinct contrast to his esteemed colleagues: Huang Gongwang , Ni Zan , and Wang Meng .

Huang Gongwang was the eldest, known for his calm, expansive landscapes, particularly his masterpiece Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains. His brushwork is often described as "boneless" and flowing, creating a sense of natural ease and profound tranquility.

Ni Zan is celebrated for his sparse, minimalist landscapes, often depicting a few lonely trees, an empty pavilion, and distant hills. His style is characterized by its dry brushwork, delicate ink tones, and an air of cool detachment and purity.

Wang Meng, the youngest of the group and a grandson of Zhao Mengfu, created dense, writhing landscapes filled with intricate details and dynamic energy. His brushwork is complex and agitated, conveying a sense of inner turmoil or overwhelming natural forces.

Compared to these three, Wu Zhen's style is often seen as more somber, earthy, and direct. While Huang Gongwang's landscapes are serene and Ni Zan's are ethereal, Wu Zhen's possess a weighty, moist, and almost brooding quality. His brushwork is less overtly complex than Wang Meng's but carries an undeniable power and directness. Despite these differences, all four masters shared a commitment to personal expression, the integration of calligraphy and poetry with painting, and a deep reverence for earlier artistic traditions, which they reinterpreted to create highly individualistic styles that became foundational for later Ming and Qing dynasty literati painting. Other notable Yuan painters who contributed to the rich artistic milieu of the time include Zhao Mengfu, whose influence was pervasive, Gao Kegong , known for his misty landscapes, Sheng Mou , whose more polished and accessible style was popular, and Cao Zhibai , another literati painter known for his spare and elegant landscapes.

Anecdotes and Enduring Character

Several anecdotes surround Wu Zhen, painting a picture of a man of unique character and perhaps even prescient abilities. One story, recorded in the Yimen Wu Shi Pu , tells of his elder brother, Wu Huang , who was skilled in the esoteric arts of the Yijing (Book of Changes) and supposedly predicted the exact time of Wu Zhen's death. Another version suggests Wu Zhen himself foresaw his passing and died peacefully at the foretold time. Such stories, whether apocryphal or not, contribute to the mystique of the artist as someone deeply attuned to the rhythms of nature and existence.

His simple lifestyle, his dedication to his art despite poverty, and his self-styling as the "Plum Blossom Monk" all point to a man who lived by his convictions. After his death, he was buried near his Plum Blossom Hermitage, and his tomb was marked with a stele inscribed "Meihua Heshang zhi Ta" . Centuries later, during the late Ming or early Qing period, the renowned artist and connoisseur Dong Qichang wrote an essay titled "Meihua An Ji" , further cementing Wu Zhen's legacy and the significance of his chosen retreat. Dong Qichang, a pivotal figure in shaping the canon of Chinese painting, held Wu Zhen in high esteem, recognizing the profound depth and integrity of his work.

Legacy and Influence

Wu Zhen's influence on subsequent generations of painters has been profound and enduring. His emphasis on strong, calligraphic brushwork, his mastery of ink, and the emotional depth of his paintings provided a powerful model for later literati artists. During the Ming Dynasty, painters like Shen Zhou and Wen Zhengming , leaders of the Wu School of painting, looked back to the Yuan masters, including Wu Zhen, for inspiration in their efforts to revive and develop the literati tradition. While court painters of the Ming, such as Dai Jin and Xie Huan , often pursued more polished and decorative styles, the individualistic and expressive qualities of Wu Zhen's art continued to resonate with scholar-painters.

His work was also highly appreciated in Japan, where Chinese literati painting, particularly from the Song and Yuan dynasties, had a significant impact on the development of Japanese ink painting (Suibokuga). The somber strength and spiritual depth of Wu Zhen's art found a receptive audience among Japanese Zen monks and artists. Even into the 20th century, modern Chinese masters continued to study and draw inspiration from Wu Zhen's powerful brushwork and his unwavering commitment to artistic integrity. Artists like Qi Baishi and Huang Binhong , while developing their own unique styles, shared Wu Zhen's profound connection to nature and his mastery of the expressive potential of ink.

Conclusion: An Enduring Spirit in Ink

Wu Zhen remains a towering figure in the history of Chinese art. His life as a recluse, his profound connection to nature, his mastery of ink, and his unwavering artistic integrity all contribute to his enduring appeal. In an era of foreign domination and social upheaval, he, along with the other Yuan masters, demonstrated the resilience of the Chinese scholarly tradition and its capacity for profound artistic innovation. His paintings of fishermen, bamboo, and somber landscapes are not mere representations of the external world but are deeply personal expressions of his inner spirit, imbued with a sense of melancholy, strength, and timelessness. Wu Zhen's legacy is a testament to the power of art to transcend worldly concerns and to communicate the deepest human emotions and philosophical insights through the simple yet infinitely expressive medium of ink on paper. His work continues to inspire and move viewers, offering a glimpse into the soul of a true literati master.