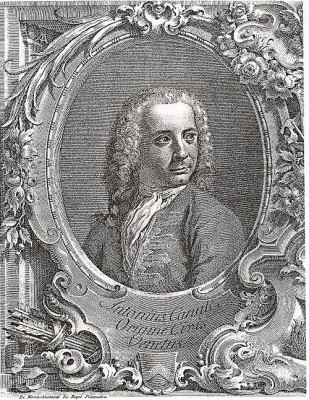

Giovanni Antonio Canal, known universally as Canaletto, stands as one of the towering figures of 18th-century European art. Born in Venice on October 28, 1697, and dying there on April 19, 1768, his life spanned a period of immense cultural flourishing and gradual political decline for the Venetian Republic. He became the pre-eminent painter of vedute, or city views, particularly those of his native Venice, capturing its unique light, architecture, and bustling life with unparalleled precision and atmospheric brilliance. His work not only defined the image of Venice for generations but also significantly influenced the course of landscape and cityscape painting across Europe.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Canaletto's artistic journey began under the tutelage of his father, Bernardo Canal, a recognized painter of theatrical scenery. This early training in perspective and stage design provided a foundational understanding of creating convincing spatial illusions, a skill that would become central to his later work. Working alongside his father and possibly his brother, the young Giovanni Antonio learned the craft of large-scale decorative painting, absorbing the techniques required to depict architectural settings for the Venetian stage. His mother was Artemisia Barbieri.

A pivotal moment occurred around 1719-1720 when Canaletto traveled to Rome. The Eternal City, with its magnificent ancient ruins and Baroque splendor, was a magnet for artists. While there, he reportedly abandoned theatrical design, inspired by the work of Giovanni Paolo Pannini, a leading Roman vedutista known for his detailed views of Rome's monuments and festivities. Pannini's meticulous approach to architectural rendering and his ability to populate scenes with lively figures likely made a strong impression on the young Venetian. This Roman sojourn solidified Canaletto's decision to specialize in topographical painting.

Upon returning to Venice around 1720, Canaletto was registered in the Venetian painters' guild, the Fraglia dei Pittori. He began to establish his reputation, initially perhaps building upon the style of Luca Carlevarijs, an older artist who had pioneered the genre of Venetian view painting. However, Canaletto quickly developed his own distinct style, characterized by a brighter palette, stronger contrasts of light and shadow, and an even greater emphasis on topographical accuracy than Carlevarijs.

The Rise of the Veduta Painter

The 18th century witnessed the height of the Grand Tour, the traditional journey undertaken by young European, particularly British, aristocrats to complete their education and absorb classical culture. Venice, with its unique beauty, republican mystique, and vibrant social life, was an essential stop. These wealthy travelers created a fervent market for high-quality souvenirs, and Canaletto's detailed and luminous paintings of the city perfectly met this demand. His views became the ultimate mementos of Venice.

A crucial figure in Canaletto's commercial success was Joseph Smith, an English merchant, collector, and later the British Consul in Venice. Smith became Canaletto's primary agent and patron, commissioning numerous works for his own collection and facilitating sales to his extensive network of British clients. Smith's Palladian villa on the Grand Canal was filled with Canaletto's works, serving as a de facto showroom. This patronage ensured Canaletto's financial security and cemented his fame abroad, particularly in England.

Canaletto's vedute were more than mere topographical records. While accuracy was paramount, he masterfully manipulated perspective and light to enhance the dramatic effect and capture the specific atmosphere of Venice. He often used a wide-angle perspective, sometimes subtly combining viewpoints to create a more comprehensive or aesthetically pleasing composition than a single vantage point would allow. His scenes teem with life – gondolas gliding on the canals, merchants haggling, elegantly dressed figures strolling in the Piazza San Marco – providing a vivid snapshot of 18th-century Venetian society.

Artistic Style and Technique

Canaletto's style is defined by its clarity, precision, and luminous quality. He possessed an extraordinary ability to render complex architectural details with accuracy, capturing the textures of stone, brick, and water. His depiction of light is particularly noteworthy; he masterfully conveyed the bright Adriatic sunlight reflecting off the water and illuminating the facades of palazzi and churches, as well as the deep, cool shadows that define form and create spatial depth. This interplay of light and shadow gives his paintings a remarkable sense of realism and vibrancy.

To achieve this high degree of accuracy, Canaletto is known to have employed optical aids, most notably the camera obscura. This device, essentially a darkened box or room with a small lens, projects an image of the external scene onto a surface inside, which the artist could then trace or use as a guide for composition and perspective. While the camera obscura aided in achieving topographical correctness, it was merely a tool. The final painting, with its nuanced color, atmospheric effects, and artistic interpretation of light, was the product of Canaletto's exceptional skill and vision.

His process often involved meticulous preparatory drawings, executed on site, capturing specific details and compositional elements. These drawings, often works of art in their own right, reveal his keen observational powers and fluid draftsmanship. In the studio, these sketches, possibly aided by camera obscura outlines, were translated into finished oil paintings. His early works often feature a bolder application of paint and dramatic contrasts, influenced perhaps by artists like Marco Ricci, known for his landscapes and ruin paintings. Over time, his brushwork became finer and his palette often cooler and more controlled, especially in works produced for the English market.

Canaletto also explored the capriccio, a genre of architectural fantasy painting popular in 18th-century Italy. Unlike the topographically accurate vedute, capricci combined real and imaginary buildings in invented settings, often featuring classical ruins. These works allowed Canaletto greater imaginative freedom and showcased his compositional ingenuity, drawing perhaps on the influence of artists like Marco Ricci who excelled in this genre.

Masterworks of Venice

Canaletto's depictions of Venice form the core of his oeuvre and include some of the most iconic images in Western art. Among his most celebrated early works is The Stonemason's Yard (c. 1726-1730). Unlike his grander, more formal views, this painting offers an intimate glimpse into a working area near the Grand Canal, depicting the Campo San Vidal with temporary workshops. Its informal composition, warm light, and focus on everyday life distinguish it and highlight Canaletto's versatility.

His views of the Grand Canal are numerous and justly famous. He painted it from various vantage points, capturing iconic landmarks such as the Rialto Bridge, the Church of Santa Maria della Salute at the entrance to the canal, and the facades of the magnificent palazzi lining its banks. Works like The Grand Canal and the Church of the Salute (c. 1730) exemplify his ability to combine architectural grandeur with the bustling activity of canal life – gondolas, barges, and figures animating the scene under a luminous sky.

The heart of Venice, Piazza San Marco and the Piazzetta, was another favorite subject. Canaletto depicted St. Mark's Basilica, the Doge's Palace, the Campanile, and the Procuratie buildings repeatedly, capturing the ceremonial and social life of this grand public space. Paintings like Piazza San Marco, Venice (c. 1730-1735) showcase his mastery of perspective, his ability to handle large crowds of figures, and his sensitivity to the changing light conditions throughout the day. These works contrast interestingly with the genre scenes of everyday Venetian life captured by his contemporary Pietro Longhi, or the later, more atmospheric and impressionistic views of the city by Francesco Guardi.

Canaletto also painted numerous views of other Venetian churches, squares, and canals, creating a comprehensive visual record of the city. His depictions of festivals and ceremonies, such as the Bucintoro ceremony (the Doge's marriage to the sea), further enriched his portrayal of Venetian life and spectacle, rivaling the grand decorative schemes of his famous contemporary, Giambattista Tiepolo, albeit on a different scale and with a different focus.

The English Decade

The War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) disrupted travel on the continent, significantly reducing the flow of Grand Tourists to Venice and impacting Canaletto's primary market. Likely prompted by this downturn and encouraged by his English connections, Canaletto moved to England in 1746, where he remained, with a couple of brief returns to Venice, until around 1755 or 1756.

In England, Canaletto found new patrons among the aristocracy and gentry who were already familiar with his Venetian works. He adapted his skills to depict English landscapes and cityscapes. London became a major subject, with numerous views of the River Thames, including depictions of the newly built Westminster Bridge and landmarks like St. Paul's Cathedral and Somerset House. These paintings often adopted the high viewpoints and panoramic scope characteristic of his Venetian vedute. He captured the bustling river traffic and the distinct, often hazier, light of London.

Beyond the capital, Canaletto received commissions to paint views of country houses and estates, such as Windsor Castle, Warwick Castle, Alnwick Castle, and Badminton House. These works required him to adapt his style to the greener, rolling landscapes of England, different from the stone and water environment of Venice. His English works were influential on native topographical painters like Samuel Scott, who adapted Canaletto's clarity and compositional structures to British scenes.

However, Canaletto's English period was not without challenges. His highly polished and precise style, perhaps becoming somewhat formulaic, led some critics, notably the engraver and chronicler George Vertue, to question whether the Canaletto working in England was the same master famed for his Venetian views, or perhaps an imposter, possibly even his nephew, Bernardo Bellotto. There were rumors that his work had become mechanical. To counter these doubts, Canaletto reportedly staged public painting demonstrations. Despite these efforts, his English works are sometimes considered less inspired than his Venetian peak, though many remain impressive achievements. His time in England coincided with the flourishing careers of major British artists like William Hogarth, Thomas Gainsborough, and Joshua Reynolds, though their primary focus was portraiture and narrative scenes rather than topography.

Printmaking: The Etchings

Canaletto was not only a master painter but also a highly accomplished printmaker, specializing in etching. His etched vedute, produced mainly in the 1740s before his departure for England, represent a significant part of his artistic output. The series known as Vedute altre prese da i Luoghi altre ideate (Views, some taken from places, others invented) includes both topographical views of Venice and imaginative capricci.

His etchings display remarkable technical skill, characterized by fine, controlled lines, calligraphic flourishes, and a masterful handling of light and shadow achieved through varied biting depths and densities of hatching. The prints possess a vibrancy and spontaneity that sometimes differs from the more polished finish of his paintings. They allowed his compositions to reach a wider audience and were highly sought after by collectors across Europe. These etchings demonstrate his ability to translate his painterly vision into the graphic medium with exceptional fluency and artistic integrity.

Later Years and Bernardo Bellotto

Canaletto returned permanently to Venice around 1756. He continued to paint, though perhaps with less frequency and arguably less of the freshness of his earlier work. His style in these later years is sometimes described as becoming more mannered, with sharper contrasts and occasionally a harder linearity. Despite his international fame, he was not elected to the Venetian Academy of Painting and Sculpture until 1763, possibly due to academic snobbery that viewed landscape painting as less prestigious than history painting. His reception piece for the Academy was a capriccio, showcasing his imaginative powers.

A significant factor during Canaletto's later career and posthumous reputation is the work of his nephew, Bernardo Bellotto (1722-1780). Bellotto trained in Canaletto's studio and became a highly skilled vedutista in his own right. He absorbed his uncle's style but developed his own distinct manner, often characterized by cooler, silvery light, sharper detail (sometimes described as crystalline), and a more dramatic, almost severe, rendering of architecture.

Crucially, Bellotto often signed his works using the name "Bellotto de Canaletto" or even just "Canaletto," particularly during his successful career outside Italy, where he worked extensively for courts in Dresden, Vienna, Munich, and Warsaw. This created considerable confusion, both during their lifetimes and for centuries afterward, making attribution difficult. Bellotto's views of Northern European cities are masterpieces of topographical painting, documenting places like Dresden and Warsaw before their wartime destruction, but his use of the Canaletto name inevitably complicated the understanding of his uncle's later output and legacy.

Legacy and Influence

Giovanni Antonio Canal, 'Canaletto', holds an undisputed place as the foremost view painter of the 18th century. His work defined the image of Venice for the world, creating enduring visions of the city's unique beauty, light, and life. His paintings were immensely popular during his lifetime, particularly among British collectors, and his influence spread throughout Europe. The Royal Collection in the UK holds the largest single collection of his works, primarily acquired by George III from Consul Smith.

His influence extended to subsequent generations of artists. In Venice, Francesco Guardi adopted the veduta genre but developed a looser, more atmospheric style, capturing the poetic melancholy of the declining Republic in contrast to Canaletto's brighter clarity. In England, Canaletto's topographical precision influenced a school of watercolourists and painters specializing in landscape and architectural views. His meticulous observation and sensitivity to light and atmosphere can also be seen as precursors to later developments in landscape painting, even distantly foreshadowing the concerns of 19th-century artists like J.M.W. Turner and the Impressionists, such as Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who were fascinated by the effects of light on water and architecture.

While some later critics found his work repetitive or overly commercial, particularly in his later phases, his reputation as a master technician and an unparalleled observer of the urban environment remains secure. His paintings continue to command enormous prices at auction, attesting to their enduring appeal and historical significance. He stands alongside other giants of the Venetian Settecento like the brilliant decorative painter Giambattista Tiepolo and the sensitive pastel portraitist Rosalba Carriera, as well as earlier vedutisti like the Dutch-Italian Gaspar van Wittel (Vanvitelli) and Luca Carlevarijs, and his own talented nephew Bernardo Bellotto, as a key figure in the final flowering of Venetian art.

Conclusion

Canaletto's legacy is intrinsically linked to the city he depicted with such devotion and skill. Through his eyes, 18th-century Venice comes alive – a city of shimmering light, architectural marvels, and vibrant human activity. His technical brilliance, particularly his handling of perspective and light, combined with his keen observational powers, resulted in works that transcend mere topography to become captivating artistic statements. As the quintessential painter of the Venetian veduta, Canaletto created a body of work that not only documented a specific time and place but also continues to enchant viewers with its clarity, beauty, and masterful artistry, securing his position as a pivotal figure in the history of European art.