Introduction: A Pivotal Figure in Utrecht

Abraham Bloemaert stands as a towering figure in the art history of the Netherlands, particularly during the vibrant period known as the Dutch Golden Age. Born in Gorinchem in 1564 (though some sources suggest 1566) and passing away in Utrecht in 1651, his exceptionally long and productive career spanned a crucial era of artistic transformation. Bloemaert was not only a highly versatile and prolific painter but also a skilled printmaker, draftsman, and, perhaps most significantly, an influential teacher who shaped a generation of artists in Utrecht and beyond. His work bridged the gap between late Mannerism and the burgeoning Baroque style, incorporating diverse influences while maintaining a distinct artistic identity.

Coming from an artistic background, with his father, Cornelis Bloemaert I, being an architect and sculptor, Abraham was immersed in a creative environment from a young age. He navigated the complex religious and political landscape of his time, remaining a devout Catholic in a predominantly Protestant region, which influenced his patronage and subject matter. His vast output, encompassing historical and religious scenes, mythological narratives, genre paintings, landscapes, and even still lifes, showcases his remarkable adaptability and technical skill. Bloemaert's legacy endures not only through his own extensive body of work but also through the numerous successful artists who trained in his Utrecht studio.

Early Life and Formative Training

Abraham Bloemaert's journey into the world of art began under the initial guidance of his father, Cornelis. However, his formal training commenced in Utrecht, where the family had relocated. He studied with several masters, though perhaps not always systematically. His earliest teachers included Gerrit Splinter, himself a pupil of the renowned Antwerp painter Frans Floris, and later Joos de Beer, who had also trained under Floris. This connection to the Floris tradition likely provided Bloemaert with a foundation in the prevailing Mannerist style of the Southern Netherlands.

Seeking broader horizons, the young Bloemaert traveled to Paris around 1581-1583. During his approximately three-year stay, he continued his artistic education, reportedly studying with various masters, possibly including figures like Jean Cousin the Younger or perhaps Hieronymus Francken I (sometimes referred to as 'Maistre Herry'). This period abroad exposed him to different artistic currents, although the specific influences absorbed during this time are less clearly documented than his later stylistic shifts. Upon returning to the Netherlands, he briefly worked with his father in Utrecht before establishing himself as an independent master.

The exact year of Bloemaert's birth remains a minor point of discussion among historians, with documents supporting both 1564 and 1566. Regardless, by the late 1580s or early 1590s, he was a practicing artist, initially working in Utrecht before a brief period in Amsterdam between 1591 and 1593. He ultimately settled permanently in Utrecht, which would become the center of his long and influential career. His diverse, if somewhat fragmented, early training laid the groundwork for his later stylistic flexibility.

Artistic Evolution: From Mannerism to Baroque

Abraham Bloemaert's artistic style underwent a significant evolution throughout his long career, reflecting broader changes in European art. Initially, his work was deeply rooted in the late Mannerist style prevalent in the Northern Netherlands, particularly associated with artists in Haarlem like Hendrick Goltzius and Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem. This early phase is characterized by elegant, elongated figures often arranged in complex, dynamic compositions, artificial poses, and sometimes cool, sophisticated color palettes with striking contrasts.

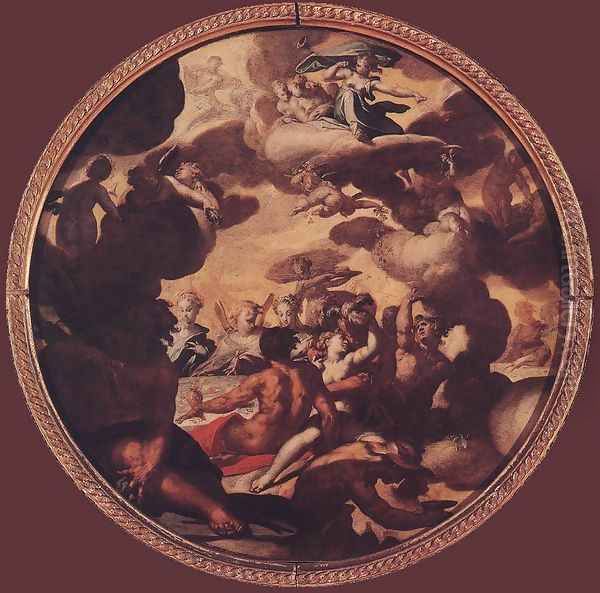

Works from the 1590s, such as his Death of the Children of Niobe, exemplify this Mannerist approach. The intricate arrangement of figures, the dramatic, almost theatrical, gestures, and the sophisticated handling of anatomy align with the ideals of late Mannerism. His color choices during this period could include distinctive greenish or greyish tones, contributing to the artificiality and elegance sought after in this style.

Around the turn of the century and particularly after 1610, Bloemaert's style began to shift towards the emerging Baroque. This transition was partly influenced by the general artistic trends moving towards greater naturalism and dramatic effect. While Bloemaert himself never traveled to Italy, the heartland of the Baroque, he was keenly aware of developments there, especially the revolutionary work of Caravaggio. This awareness likely came through prints and, more directly, through the return of his own students from Italy.

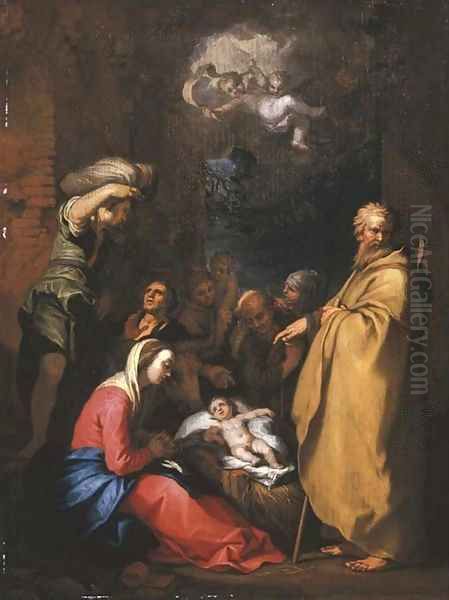

The influence of Caravaggism, characterized by dramatic chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark) and a heightened sense of realism, became increasingly apparent in Bloemaert's work from the 1610s and 1620s. Paintings like The Adoration of the Magi or The Adoration of the Shepherds from this period often feature strong lighting effects, more robust and naturalistic figures, and a greater emotional directness compared to his earlier Mannerist pieces. However, Bloemaert rarely adopted the full intensity or gritty realism of Caravaggio, instead blending these elements with his existing style.

The Utrecht Caravaggisti and Bloemaert's Studio

One of Abraham Bloemaert's most enduring contributions to Dutch art history was his role as a teacher. His Utrecht studio became a major center for artistic training, attracting numerous aspiring painters. Crucially, several of his students traveled to Italy, particularly Rome, where they directly encountered the works of Caravaggio and his followers like Orazio Gentileschi and Bartolomeo Manfredi. Upon their return to Utrecht in the early 1620s, these artists formed the core of the movement known as the Utrecht Caravaggisti.

Key figures among Bloemaert's pupils who became leading Utrecht Caravaggisti include Hendrick ter Brugghen and Gerard van Honthorst. Dirck van Baburen, another central figure of the movement, also likely had contact with Bloemaert's circle, though direct tutelage is less certain. These artists brought back a style characterized by dramatic tenebrism (use of deep shadow), realistic depictions of often common-looking figures in religious or genre scenes, and a focus on nocturnal settings, especially in the case of Honthorst, who earned the nickname 'Gherardo delle Notti' (Gerard of the Night Scenes) in Italy.

While Bloemaert himself did not paint in a fully Caravaggesque manner, his openness to new styles and his position as the leading master in Utrecht created an environment where this new Italianate influence could flourish. His own work from the 1620s shows his engagement with the Caravaggesque idiom, seen in his increased use of chiaroscuro and more naturalistic figure types, even if often softened or adapted to his own preferences. He effectively served as a bridge, connecting the older Mannerist traditions with the new Baroque trends imported by his students.

Beyond the famous Caravaggisti, Bloemaert's studio trained a wide array of other significant artists. These include painters with diverse specializations, such as Cornelis van Poelenburgh, known for his Italianate landscapes with small figures; Jan Both and his brother Andries Both, also pioneers of Dutch Italianate landscape painting; the genre and portrait painter Jan van Bijlert; and Jacob Gerritsz. Cuyp, father of the more famous Aelbert Cuyp. Jan Baptist Weenix, known for Italianate landscapes and still lifes, also studied with him. This diverse group underscores the breadth of Bloemaert's teaching and influence.

Bloemaert also trained his own four sons: Hendrick, Frederick, Cornelis II, and Adriaen. All became artists, with Hendrick working closely in his father's style, Frederick becoming a notable engraver who reproduced his father's designs, Cornelis II achieving fame as an engraver in Paris and Rome, and Adriaen working as a painter in Utrecht, Salzburg, and possibly Denmark. The sheer number and quality of artists emerging from his studio testify to his importance as an educator.

Master Draftsman and Printmaker

Abraham Bloemaert was not only a prolific painter but also an exceptionally gifted draftsman and a significant designer of prints. His surviving drawings number around 1700, showcasing his skill across various techniques, including pen and ink, chalk, and wash. These drawings range from quick sketches capturing initial ideas to highly finished preparatory studies for paintings and designs for engravings. His drawings often reveal his working process, his exploration of composition, and his keen observation of the human figure, animals, and landscape elements.

His drawings of rustic subjects, such as dilapidated farmhouses, peasants at work, and studies of trees and foliage, were particularly influential. These studies, often drawn from life or inspired by the Dutch countryside, provided source material for his landscape paintings and were highly sought after by collectors and other artists. A work like Study of Three Arms and Hands demonstrates his meticulous attention to anatomical detail and his fluid, confident line work.

Bloemaert frequently collaborated with leading engravers of his time to translate his designs into prints, making his compositions accessible to a wider audience. He worked with prominent figures like Jacob Matham (stepson of Hendrick Goltzius), Willem van Swanenburg, Boetius Adamsz. Bolswert, and his brother Schelte Adamsz. Bolswert. His son, Frederick Bloemaert, became a key engraver of his father's later designs, ensuring the continued dissemination of his work.

The prints after Bloemaert's designs covered the same wide range of subjects found in his paintings: biblical stories, mythological scenes, allegories, genre figures, and landscapes. These prints played a crucial role in spreading his artistic influence both within the Netherlands and internationally. They served as models for other artists and contributed significantly to his reputation.

Furthermore, Bloemaert compiled his drawings, particularly figure studies and pastoral elements, into a drawing book known as the Konstryk Tekenboek (Artistic Drawing Book). First published possibly around 1650-1656, primarily featuring engravings by his son Frederick after his drawings, this book became an immensely popular and enduring instructional manual for art students. It was reprinted numerous times well into the 18th and even 19th centuries, demonstrating the long-lasting impact of his approach to drawing and teaching. The Tekenboek codified his method of constructing figures and compositions, influencing generations of artists learning the fundamentals of art.

Themes, Patronage, and Religious Conviction

Abraham Bloemaert tackled an impressive variety of themes throughout his career. Religious subjects drawn from both the Old and New Testaments were a constant feature, reflecting his personal Catholic faith and the demands of patrons. Key works include multiple versions of The Adoration of the Shepherds, The Adoration of the Magi, Moses Striking the Rock, and The Annunciation. His depictions often blend narrative clarity with dynamic compositions and rich coloring.

Mythological and allegorical subjects also feature prominently in his oeuvre. Scenes from classical mythology, such as The Wedding of Peleus and Thetis or depictions of gods and goddesses like Apollo and Artemis, allowed him to explore complex narratives and showcase his skill in rendering the human form, often in elegant or dramatic poses inherited from his Mannerist background but later infused with Baroque energy.

Landscape painting evolved significantly in Bloemaert's hands. While early landscapes often served as backdrops for religious or mythological scenes (e.g., The Flight into Egypt), he increasingly produced landscapes where the natural or rustic setting itself became the primary focus. His characteristic landscapes often feature picturesque, slightly dilapidated farm buildings, rustic figures, and prominent trees, rendered with a blend of observation and idealized composition. These works contributed to the development of Dutch landscape painting as an independent genre.

Genre scenes, depicting peasants resting, eating, or engaged in everyday activities, also appear in his work, particularly during his middle period when Caravaggesque influence was strong. These scenes often carry moralizing undertones but are also appreciated for their lively characterization and realistic details.

As a devout Catholic living and working in Utrecht, which after the Reformation was officially Protestant but retained a significant Catholic minority, Bloemaert occupied a unique position. While public commissions for Catholic churches were impossible, there was a substantial market for religious art for clandestine Catholic churches ('schuilkerken') and private Catholic homes. Bloemaert became a leading provider of such works, creating altarpieces and devotional paintings for this community. His faith likely informed the sincerity and frequency of his religious depictions. His patrons included not only private citizens but also Catholic institutions operating discreetly within Utrecht and sometimes further afield, possibly including commissions for churches in the Southern Netherlands (e.g., Brussels).

Later Career, Style, and Personal Life

In the later decades of his career, from the 1630s until his death in 1651, Bloemaert's style continued to evolve, often moving towards a more classical and sometimes decorative elegance. While the dramatic chiaroscuro of the 1620s might soften, his compositions remained dynamic, and his colors often became brighter and more varied. Works from this period, like Lot and His Daughters or The Marriage of Cupid and Psyche, showcase his enduring skill in complex multi-figure compositions and his ability to adapt his style. Some later works exhibit a lighter palette and a more graceful, almost Rococo sensibility, anticipating later trends.

He remained remarkably productive into his old age, running his successful workshop and continuing to paint, draw, and design prints. His reputation remained high, and he was considered the venerable patriarch of the Utrecht art scene. His influence extended beyond his direct pupils; even Peter Paul Rubens, the Flemish Baroque giant, reportedly visited Bloemaert during a trip to the Dutch Republic and expressed admiration for his work, highlighting Bloemaert's esteemed position.

Regarding his personal life, Bloemaert married twice. His first wife, Judith van Schonenburch, whom he married around 1592 in Utrecht, died relatively young, possibly childless. He remarried in 1600 to Gerarda de Roij, with whom he had numerous children, including the four sons who followed him into artistic careers (Hendrick, Frederick, Cornelis II, Adriaen). Having many children, possibly around eight or more who survived infancy, was not uncommon, though the figure of fourteen mentioned in one source might be an exaggeration or include stepchildren/infant deaths. His second wife passed away in 1649, predeceasing him by two years.

There is some mention in sources of Bloemaert holding civic positions, possibly even serving briefly as a mayor or council member around 1618-1620, potentially linked to his standing within the Catholic community during a period of political tension between different factions (Remonstrants and Counter-Remonstrants). However, details about his political involvement remain somewhat unclear and require careful verification. His primary identity throughout his life was undoubtedly that of an artist and teacher. He died at a venerable age in Utrecht and was buried in the Catharijnekerk.

Controversies and Attribution Challenges

Like many prolific artists with active workshops and artist family members, Abraham Bloemaert's oeuvre presents some attribution challenges and minor controversies. The close stylistic relationship between Abraham and his son Hendrick Bloemaert, who worked as his assistant and continued in a similar style, has sometimes led to confusion in attributing works, particularly from Abraham's later period. Some paintings initially given to the father have later been reconsidered as potentially by Hendrick or as workshop productions.

The specific example mentioned in the source material regarding a Lot and His Daughters painting being attributed first to Jacob Jordaens and then to Bloemaert's son seems somewhat confused, as Jordaens' style is quite distinct. It might refer to a specific workshop version or a copy, or perhaps conflates different paintings. However, the general issue of distinguishing between the master's hand, his son Hendrick's contributions, and other workshop output is a real challenge for connoisseurs and art historians studying the Bloemaert legacy.

The discrepancy regarding his birth year (1564 vs. 1566) is a minor historical controversy based on conflicting documentary evidence, though it has little bearing on the assessment of his artistic career. Similarly, the precise identities of all his teachers in Paris remain somewhat speculative, based on interpretations of early biographical accounts like that of Karel van Mander in his Schilder-boeck (1604).

His ability to adapt his style, sometimes referred to as being an "artistic chameleon," while a testament to his versatility, could occasionally lead to questions about stylistic consistency. However, this adaptability is now generally seen as a strength, allowing him to effectively tackle a wide range of subjects and respond to changing artistic tastes over his exceptionally long career. These minor points and attribution issues do not detract from his overall importance but are part of the ongoing scholarly work surrounding his life and art.

Enduring Influence and Legacy

Abraham Bloemaert's influence on Dutch art was profound and multifaceted. As the leading painter in Utrecht for decades and a highly sought-after teacher, he directly shaped the careers of many artists who went on to achieve significant fame in their own right. His role in nurturing the Utrecht Caravaggisti (Ter Brugghen, Honthorst) was pivotal, making Utrecht a unique center where Italian Baroque influences were assimilated and transformed within a Dutch context.

His impact extended to landscape painting through pupils like Cornelis van Poelenburgh and the Both brothers, who pioneered the popular genre of Dutch Italianate landscapes. His rustic landscape drawings and paintings also influenced artists focused on more native Dutch scenery. Through his widely circulated prints and his influential drawing book, his compositions and figure types became known far beyond his immediate circle, impacting artists across the Netherlands and even abroad. Artists in later generations, like the French Rococo painter François Boucher, are known to have copied Bloemaert's drawings, attesting to their enduring appeal.

While direct influence on towering figures like Rembrandt or Vermeer is difficult to prove and likely minimal, Bloemaert contributed significantly to the overall artistic climate of the Dutch Golden Age. He maintained a high standard of craftsmanship and professionalism, successfully navigated the art market, and demonstrated how an artist could thrive even outside the main centers of Amsterdam or Haarlem. His long career bridged the transition from Mannerism to Baroque, and his adaptability ensured his relevance across changing tastes.

Today, Abraham Bloemaert's works are held in major museums worldwide, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Centraal Museum in Utrecht, the Louvre in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery in London, and the Hermitage in St. Petersburg. Exhibitions, such as "The Bloemaert Effect" held in Utrecht in 2011-2012, continue to explore his work and his extensive impact on his contemporaries and followers. He remains recognized as a versatile master, a crucial educator, and a central figure in the rich tapestry of 17th-century Dutch art.