Introduction: An Artist of His Time

Leopold Schmutzler stands as a fascinating, albeit complex, figure in the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century German art. Born in Bohemia but primarily active in Munich, Schmutzler navigated the shifting artistic currents of his era, achieving considerable fame for his elegant portraits, captivating depictions of the female form, and scenes imbued with a Rococo sensibility. His technical skill was undeniable, earning him prestigious commissions and a place among the popular artists of his day. However, his later career became inextricably linked with the rise of National Socialism in Germany, casting a long shadow over his legacy and prompting ongoing debate about the relationship between art, artists, and political ideology. This exploration delves into the life, work, and contested reputation of Leopold Schmutzler, examining his artistic journey from the academies of Vienna and Munich to the salons of the elite, and ultimately, to the controversial exhibitions of the Third Reich.

Bohemian Roots and Artistic Formation

Leopold Schmutzler was born on March 29, 1864, in Mies (now Stříbro), a town in Bohemia, which was then part of the Austrian Empire (later Austria-Hungary). His birthplace, though now within the Czech Republic, situated him within the broader German-speaking cultural sphere that would dominate his artistic life. He hailed from a relatively comfortable background; his father was reportedly an innkeeper, saddler, and shop owner, suggesting a certain level of bourgeois stability. His mother worked as a seamstress. This environment seemingly fostered his early artistic inclinations, as it's recorded that his father provided him with his initial drawing lessons, recognizing and encouraging his burgeoning talent.

An early ambition pointed towards a different path. Schmutzler initially considered a career in music and planned to attend the Naval Music School in Pula (now in Croatia), a major Austro-Hungarian naval base. However, this plan was thwarted due to poor eyesight, a physical limitation that redirected his focus firmly towards the visual arts. This rejection, while perhaps a personal disappointment at the time, proved pivotal in setting the course for his future profession as a painter.

His formal artistic training began around 1880 at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. There, he studied under Christian Gripenkerl, a notable academic painter known for his historical compositions and portraits. Vienna, as the imperial capital, was a vibrant hub of artistic activity, though its Academy was often seen as quite conservative. Schmutzler's time in Vienna lasted approximately two years, until 1882. Sources suggest he may not have fully integrated or been formally accepted into the master class, prompting his move to another major artistic center.

Seeking further development, Schmutzler relocated to Munich, the capital of Bavaria and a rival to Vienna and Berlin as a leading German art city. He enrolled in the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, a renowned institution that had trained generations of German artists. In Munich, he became a student of Otto Seitz, a painter associated with the Munich School, known for his genre scenes and historical subjects, often rendered with meticulous detail. The Munich Academy, particularly during this period, emphasized strong draftsmanship and a realistic approach, influences that would remain evident throughout Schmutzler's career. He eventually settled in Munich, which would become the primary base for his artistic activities and where he would build his reputation.

Development of a Distinctive Style: Realism Meets Rococo

Leopold Schmutzler's artistic style evolved into a distinctive blend of academic realism, infused with elements drawn from Rococo aesthetics and, to some extent, the decorative sensibilities of Art Nouveau (Jugendstil). His training under figures like Gripenkerl and Seitz grounded him in the solid draftsmanship and representational accuracy valued by the academies of the time. This realistic foundation is apparent in the careful rendering of anatomy, textures, and facial features in his works.

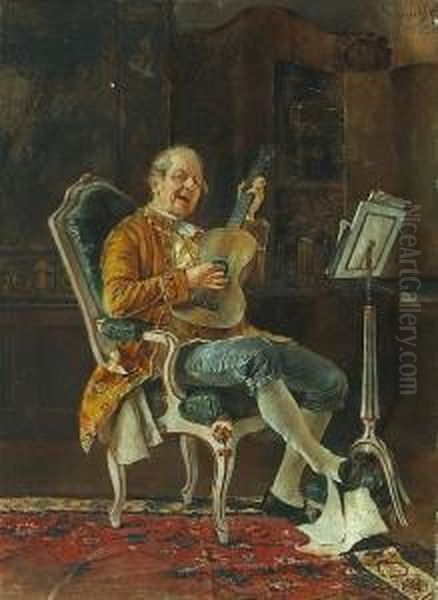

However, Schmutzler distinguished himself by frequently incorporating a lighter, more decorative touch reminiscent of the 18th-century Rococo period. This was particularly evident in his choice of subjects – elegant women in fashionable attire, often placed in opulent interiors or idyllic garden settings – and in his handling of paint, which could be both precise and fluid. He showed a fondness for graceful poses, delicate details in clothing and accessories, and a generally bright, appealing color palette. This Rococo revivalism was not unique to Schmutzler; it was part of a broader trend in late 19th-century European art and design that looked back to earlier historical styles.

His subject matter largely centered on the female figure. He became particularly known for his society portraits, capturing the likenesses of elegant women from Munich's upper classes and artistic circles. Alongside these formal commissions, he frequently painted genre scenes featuring women, often in idealized rural settings or intimate domestic interiors. A significant portion of his oeuvre also included depictions of dancers, actresses, and semi-nude or nude figures. These works often played with themes of beauty, grace, and sometimes a subtle eroticism, rendered with a polished technique that made them highly popular with collectors.

Compared to some of his contemporaries in Munich, like the celebrated portraitist Franz von Lenbach, known for his more somber and psychologically penetrating portraits of prominent figures, Schmutzler's work often presented a more idealized and decorative vision. While Lenbach aimed for gravitas, Schmutzler often emphasized charm and elegance. His style also stood in contrast to the emerging modernist movements. While artists associated with German Impressionism, such as Max Slevogt or Lovis Corinth (who also worked extensively in portraiture but with a much looser, more expressive style), were exploring new ways of capturing light and emotion, Schmutzler largely remained committed to a more polished, academic finish. Similarly, his work bore little resemblance to the bold colors and distorted forms of the nascent Expressionist groups like Die Brücke, whose members included Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

Success in Munich: Portraitist of the Elite

Settling in Munich proved advantageous for Schmutzler. The city was not only an artistic hub but also the capital of the Kingdom of Bavaria, boasting a royal court and a thriving bourgeoisie eager to commission artworks. Schmutzler rapidly established himself as one of the city's most sought-after portrait painters during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His ability to combine accurate likenesses with an elegant, flattering style made him particularly popular among the elite.

His clientele included members of the Bavarian royal family, the Wittelsbachs. Receiving commissions from royalty was a significant mark of success and prestige for any artist of the period, solidifying Schmutzler's reputation and likely leading to further commissions from aristocratic and wealthy patrons. His portraits from this era often depict his sitters in luxurious attire, surrounded by indicators of their status, rendered with the detailed, polished technique that became his hallmark.

Beyond royalty and the aristocracy, Schmutzler also attracted commissions from the world of theatre and dance. Munich had a vibrant cultural scene, and he painted portraits of several well-known performers. His skill in capturing not just a likeness but also a sense of personality and perhaps the theatricality of his subjects made him a favored choice. These portraits often allowed for more dynamic compositions and elaborate costumes than traditional society portraits, aligning well with his decorative inclinations.

His success was reflected in his participation in major exhibitions, likely including those held at Munich's famous Glaspalast (Glass Palace), a major venue for international art exhibitions until its destruction by fire in 1931. Exhibiting in such prestigious venues was crucial for an artist's visibility and marketability. Schmutzler's appealing style, combining technical proficiency with elegant subject matter, resonated with the tastes of the time, ensuring a steady demand for his work. He operated within a competitive Munich art scene that included established figures like Franz Defregger, known for his Tyrolean genre scenes, and Eduard von Grützner, famous for his depictions of cheerful monks, but Schmutzler carved out his niche with his focus on elegant femininity and Rococo charm.

Representative Works: Elegance and Controversy

Several key works exemplify Leopold Schmutzler's style and highlight different phases of his career, including the later, more controversial period.

Salome: This painting is one of Schmutzler's most famous works, depicting the biblical femme fatale. Often identified as a portrait of the actress Lili Marberg in the role, the painting showcases Schmutzler's engagement with popular themes of the fin-de-siècle, where Salome was a recurring subject explored by artists like Gustav Klimt and Franz von Stuck. Schmutzler's version emphasizes the figure's alluring presence and elaborate costume, rendered with his characteristic attention to detail and decorative flair. It blends portraiture with a historical/mythological theme, capturing the theatricality associated with the subject.

Lady at the Fountain: This work is a quintessential example of Schmutzler's Rococo-inspired style. It typically depicts an elegantly dressed young woman in an idyllic garden setting, often near a decorative fountain. The mood is light, graceful, and slightly nostalgic. The focus is on feminine beauty, delicate fabrics, and the pleasant atmosphere of leisure. Such paintings catered to the tastes of patrons who appreciated refined aesthetics and idealized representations of femininity, showcasing Schmutzler's skill in creating charming, visually appealing compositions.

Farm Girl Returning Home (Arbeitsmaid vom Felde heimkehrend): This painting represents a shift, particularly associated with his later career and alignment with Nazi ideology. While Schmutzler had painted rural scenes earlier, works like this took on a different connotation during the Third Reich. It depicts a young, healthy-looking woman, presumably returning from agricultural work. The style remains realistic, but the subject matter aligns with the "Blut und Boden" (Blood and Soil) ideology promoted by the Nazis, which glorified rural life, manual labor, and the perceived purity of the German peasantry. The figure is often presented as robust and virtuous, embodying an idealized vision of German womanhood according to Nazi aesthetics.

Working Young Woman (Die arbeitende jüngere Frau / Mädel nach der Arbeit): Created around 1940, this work further exemplifies Schmutzler's art during the Nazi era. It portrays a young woman, seemingly resting after physical labor, embodying health, strength, and diligence. This painting was exhibited at the Great German Art Exhibition (Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung) in Munich, the official showcase for art approved by the Nazi regime. Significantly, this work was purchased by Adolf Hitler himself for a considerable sum, highlighting Schmutzler's acceptance and favor within the Nazi cultural establishment. The painting served as propaganda, promoting the image of the hardworking, racially "pure" German woman contributing to the nation.

These works illustrate the trajectory of Schmutzler's career: from the elegant, market-friendly paintings of his early and middle periods to the ideologically charged works of his later years. While technically consistent, the thematic content and political context of his later works fundamentally altered his legacy.

The Nazi Era: Collaboration and Complication

The rise of the Nazi Party to power in 1933 marked a significant turning point in German cultural life and in Leopold Schmutzler's career. While many artists faced persecution, censorship, or exile – particularly those associated with modernism, Jewish artists, or political opponents – others found opportunities by aligning themselves with the new regime. Schmutzler, already in his late 60s when Hitler became Chancellor, appears to have embraced the cultural policies of the Third Reich.

From the mid-1930s onwards, Schmutzler became a supporter of the Nazi Party and adapted his artistic output to conform to its aesthetic and ideological demands. The Nazi regime promoted a style of art that was realistic, easily understandable, and glorified themes central to its ideology: racial purity, family values, heroism, rural life ("Blood and Soil"), and the dignity of labor. Art considered "degenerate" (Entartete Kunst) – including Expressionism, Cubism, Surrealism, and works by Jewish artists – was purged from museums and public life, famously culminating in the "Degenerate Art" exhibition of 1937.

Schmutzler's existing realistic style and his focus on idealized figures, particularly women, could be relatively easily adapted to fit the Nazi mold. He began producing works that explicitly promoted Nazi ideals, such as the aforementioned Farm Girl Returning Home and Working Young Woman. These paintings were exhibited in the officially sanctioned Great German Art Exhibitions held annually at the Haus der Deutschen Kunst (House of German Art) in Munich from 1937 onwards. Inclusion in these exhibitions signified official approval and patronage.

His participation was not passive; he actively contributed works that were well-received by the Nazi leadership. The purchase of Working Young Woman by Hitler in 1940 for 7,000 Reichsmarks was a clear sign of favor. Schmutzler was seen as an artist who upheld the regime's cultural values, producing art that was considered wholesome, skillful, and supportive of the national spirit. He joined a group of artists, including painters like Adolf Ziegler (nicknamed the "Master of German Pubic Hair" and a key organizer of the purge of degenerate art) and sculptors like Arno Breker and Josef Thorak, who received significant commissions and recognition during the Third Reich.

This alignment brought Schmutzler professional benefits during a period when many other artists struggled or were silenced. However, it irrevocably tied his name and work to a regime responsible for unimaginable atrocities. While some interpretations suggest his later works might contain elements of social observation, their primary function within the context of the Great German Art Exhibitions was undoubtedly propagandistic, serving to visually reinforce the ideology of the Nazi state. This collaboration remains the most controversial aspect of his life and career.

Schmutzler in Context: Comparisons with Contemporaries

Placing Leopold Schmutzler within the broader context of German and European art of his time helps to understand his position and significance. His career spanned several major artistic shifts, from the late academicism and historicism of the 19th century through the rise of Impressionism, Jugendstil, Expressionism, and ultimately, the state-controlled art of the Third Reich.

As a portraitist in Munich, Schmutzler operated alongside figures like Franz von Lenbach, who dominated the field with his powerful depictions of Bismarck and other luminaries. While both worked in a realistic vein, Lenbach's style was often darker and more focused on conveying authority, whereas Schmutzler excelled at capturing elegance and charm, particularly in his female portraits. Another contemporary Munich portraitist, Friedrich August von Kaulbach, also specialized in elegant society portraits, sharing some stylistic affinities with Schmutzler.

Schmutzler's interest in Rococo revivalism connects him to a wider European trend. In France, artists like James Tissot (though earlier) captured the elegance of modern life with meticulous detail, while academic painters like William-Adolphe Bouguereau produced highly polished, idealized nudes and mythological scenes that found immense popularity, similar to the appeal of Schmutzler's more decorative works.

His relationship with Jugendstil (Art Nouveau) is subtle but present in the decorative quality and flowing lines found in some of his works, particularly those depicting dancers or incorporating ornate patterns. However, he never fully embraced the more stylized or symbolic language of leading Jugendstil artists like Franz von Stuck (also based in Munich and known for his Symbolist paintings) or the Vienna Secessionists led by Gustav Klimt. Klimt's opulent, decorative, and often symbolic portraits, with their use of gold leaf and flattened perspectives, offer a stark contrast to Schmutzler's more conventional realism, even when both depicted elegant women.

During the rise of modernism, Schmutzler remained largely untouched by the radical innovations of German Expressionists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde (whose relationship with the Nazis was complex and ultimately negative), or Max Beckmann. These artists prioritized emotional expression and subjective experience over realistic representation, placing them in direct opposition to the academic tradition Schmutzler represented and the artistic ideals later favored by the Nazis.

In the Nazi era, Schmutzler found himself aligned with artists promoted by the regime, such as Adolf Ziegler, Paul Mathias Padua, and Werner Peiner, who produced realistic works conforming to Nazi ideology. His output during this period contrasts sharply with the art deemed "degenerate," created by the very modernists he had stylistically diverged from decades earlier. His teachers, Christian Gripenkerl in Vienna and Otto Seitz in Munich, represented the academic tradition he emerged from, a tradition that, in a distorted way, formed the basis for the technically proficient but ideologically constrained art favored by the Third Reich.

Later Life, Death, and Legacy

Leopold Schmutzler continued to work through the late 1930s, benefiting from the patronage of the Nazi regime. He died in Munich on June 20, 1941, at the age of 77, before the end of World War II and the subsequent reckoning with Nazi Germany's cultural collaborators. His death spared him from the direct consequences of post-war denazification processes that many other artists and cultural figures faced.

In the immediate post-war years, artists associated with the Nazi regime, like Schmutzler, were largely ignored or condemned. Their works, particularly those created during the Third Reich, were tainted by their association with Nazi ideology and propaganda. Museums deaccessioned works acquired during that period, and critical attention focused instead on the artists who had been persecuted or forced into exile, and on the modernist movements that the Nazis had tried to suppress. Schmutzler's name faded from mainstream art historical discourse for several decades.

However, beginning in the later 20th century and continuing into the 21st, there has been a renewed, albeit cautious, interest in the art of the Third Reich and the artists associated with it. This interest is often driven by a desire to understand the cultural mechanisms of the Nazi state, as well as by the art market, where works by artists like Schmutzler occasionally appear at auction. His earlier, pre-Nazi works, particularly the elegant portraits and Rococo-inspired scenes, are often appreciated for their technical skill and period charm, sometimes fetching significant prices.

Today, Leopold Schmutzler's legacy remains deeply complex and contested. His undeniable technical ability and the appeal of his earlier works are weighed against his willing participation in the cultural apparatus of a totalitarian regime. He cannot be easily dismissed, as he was a prominent and successful artist for much of his career. Yet, his later work serves as a stark reminder of how art can be co-opted for political purposes. Some institutions, like the Frye Art Museum in Seattle, which has holdings related to the Munich School, may include works by Schmutzler, often contextualizing them within the broader history of German art of the period.

Conclusion: An Artist of Dualities

Leopold Schmutzler's life and art embody a series of dualities: Bohemian roots and German identity, academic training and Rococo flair, popular acclaim and political compromise. He was an artist capable of producing works of considerable charm and technical finesse, capturing the elegance and aspirations of his time. His portraits and genre scenes earned him a place among the successful painters of the Munich School and catered effectively to the tastes of the late Wilhelmine and Weimar periods.

Yet, his decision to align himself with the National Socialist regime in the final decade of his life fundamentally complicates any assessment of his career. While his earlier works can be appreciated for their aesthetic qualities, his later paintings are inseparable from the toxic ideology they served to promote. Schmutzler's story serves as a case study in the complex interplay between artistic production, personal ambition, and political regimes. He remains a figure whose work requires careful contextualization, reminding us that the appreciation of art cannot always be divorced from the historical and ethical circumstances of its creation. His legacy is thus one of both accomplished artistry and profound moral ambiguity.