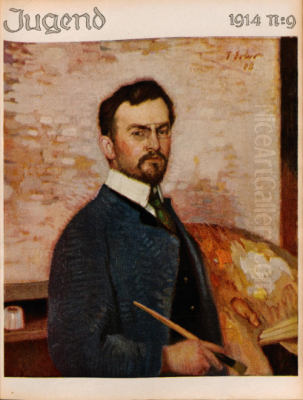

Fritz Erler (1868–1940) stands as a significant yet complex figure in German art history. A painter, graphic artist, and designer, his long career spanned a tumultuous period, witnessing the height of the German Empire, the cataclysm of World War I, the fragile Weimar Republic, and the rise and consolidation of the Third Reich. Erler was an artist of considerable technical skill and versatility, deeply involved in the key artistic movements of his time, particularly Jugendstil and the Munich Secession. However, his legacy is inevitably intertwined with his role as a prominent artist during both the First World War and, more controversially, the Nazi era. This exploration delves into his life, artistic development, major works, influences, and the historical context that shaped his path.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Frankenstein, Silesia (now Ząbkowice Śląskie, Poland), in 1868, Fritz Erler received his initial artistic training under the guidance of the decorative painter Albrecht Bräuer at the Royal Art School in Breslau (Wrocław). Like many aspiring artists of his generation, he sought broader horizons and further education in the major art capitals of Europe. He spent time in Paris, immersing himself in the vibrant artistic milieu of the French capital during the early 1890s. Studying at the Académie Julian, he would have been exposed to the lingering influence of Impressionism and the burgeoning Post-Impressionist movements, absorbing the techniques and ideas circulating in studios and galleries.

Following his time in France, Erler also traveled to Italy. This period proved particularly formative. He was deeply impressed by the work of the Italian painter Giovanni Segantini, a leading figure of Divisionism and Symbolism. Segantini's technique, characterized by its filament-like brushstrokes and often luminous, symbolic depictions of nature and rural life, left a discernible mark on Erler's developing style, particularly in his handling of light and texture in landscape and figurative works. By 1895, Erler had settled in Munich, then a major centre for German art, rivalling Berlin in importance and fostering a dynamic atmosphere of artistic innovation and debate. He later established a home and studio in Holzhausen am Ammersee, southwest of Munich, an area popular with artists.

Munich, Jugend, and the Founding of 'Die Scholle'

Munich at the turn of the century was a crucible of artistic activity. The established academic tradition coexisted, often uneasily, with newer movements seeking fresh forms of expression. One of the most influential forces was the Jugendstil, the German variant of Art Nouveau. Central to its dissemination was the lavishly illustrated magazine Jugend (Youth), founded in 1896. Fritz Erler became one of its founding members and a regular contributor, designing numerous covers and illustrations that epitomized the magazine's decorative, often linear, and symbolically rich aesthetic. His work for Jugend helped establish his reputation as a skilled graphic artist and designer.

In 1899, Erler, alongside his brother Erich Erler and other like-minded Munich artists including Leo Putz, Adolf Münzer, Walter Georgi, and Max Feldbauer, co-founded the artists' association known as 'Die Scholle' (The Clod or The Soil). The name itself suggested a connection to the native soil, perhaps implying a focus on German themes or a down-to-earth approach, distinct from international trends or academic stiffness. 'Die Scholle' was not defined by a rigid stylistic manifesto but rather by a shared desire among its members for artistic independence and a commitment to high-quality craftsmanship, often combined with decorative tendencies and an interest in plein-air painting. They exhibited together, primarily at the Munich Glaspalast, gaining recognition for their distinctive contributions to the Munich art scene. Erler emerged as a leading figure within this group until its dissolution around 1911.

A Versatile Talent: Painting, Design, and Decoration

Erler's artistic output was remarkably diverse. While primarily known as a painter, his talents extended significantly into the realms of applied arts and design, reflecting the Jugendstil ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art), where artists sought to permeate all aspects of life with aesthetic principles. He undertook major decorative commissions, most notably the frescoes for the Kurhaus (Spa Hall) in Wiesbaden, completed around 1907. These large-scale works demonstrated his ability to handle monumental compositions and integrate art within an architectural context.

His design work encompassed a wide range: he created designs for stained glass windows, furniture, ceramics, and book covers. He was also active as a stage designer, creating sets and costumes for theatrical and operatic productions, collaborating with prominent figures in the performing arts world. This engagement with stagecraft likely influenced the dramatic and sometimes theatrical quality found in his paintings.

Throughout this period, Erler also gained renown as a portraitist. He painted likenesses of notable contemporaries, including the composer Richard Strauss and the playwright Gerhart Hauptmann. These portraits often combined realistic depiction with a sense of the sitter's personality and status, rendered with the technical assurance that characterized his work. His painting style during these years often blended realistic observation with Symbolist undertones and a decorative sensibility inherited from Jugendstil, marked by strong compositions and often rich colour palettes. Works like Schwarzer Pierrot (Black Pierrot, 1908), now housed in the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich, exemplify this phase.

The Great War: Art in Service of Propaganda

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 marked a significant turning point in Erler's career, as it did for many artists across Europe. He fully embraced the nationalistic cause and channelled his artistic skills into supporting the German war effort. He became one of the official military painters appointed by the Oberste Heeresleitung (German Supreme Army Command). His most enduring contributions from this period are arguably his powerful propaganda posters, particularly those designed to promote war bonds (Kriegsanleihe).

His most famous poster, created for the sixth war bond drive in 1917, bears the stark slogan "Helft uns siegen!" (Help us conquer!). It depicts the determined, helmeted head of a German soldier, eyes shadowed but fixed forward, against a backdrop of barbed wire under a dramatic sky. The image is rendered with a bold, almost sculptural realism, conveying strength, sacrifice, and unwavering resolve. This poster became iconic and was immensely effective, reportedly contributing significantly to the success of the bond drive. Its visual language – heroic, monumental, and emotionally charged – set a standard for German war propaganda.

Beyond posters, Erler also created paintings depicting scenes from the front and idealized representations of soldiers. Works like Kämpfer vor Verdun (Fighters before Verdun, 1916), Der K (The War, 1916 and 1917 iterations likely referring to specific works or a series), and Soldat (Soldier, 1917) aimed to bolster morale on the home front and glorify the military struggle. These works often employed a heightened realism, emphasizing the perceived heroism and endurance of the German soldier. His style during the war became harder, more monumental, shedding much of the decorative elegance of his earlier work in favour of starkness and dramatic impact, aligning his art directly with the nationalistic and militaristic spirit of the time. His approach can be compared to other prominent German graphic artists of the era, such as Ludwig Hohlwein, who also produced influential war posters.

Between the Wars: The Weimar Republic and the Rise of Nazism

After the defeat of Germany in 1918 and the establishment of the Weimar Republic, Erler continued his artistic career. Following the dissolution of 'Die Scholle', he had joined the prestigious Münchner Secession, an association founded earlier (in 1892) by artists like Franz von Stuck, Wilhelm Trübner, and Lovis Corinth, who sought to break away from the conservative establishment of the Munich Artists' Cooperative. Erler's membership in the Secession placed him within the mainstream of established, albeit progressive, Munich artists. He continued to receive recognition, being made an honorary member of the Munich Academy of Fine Arts in 1922 and receiving the Bavarian Maximilian Order for Science and Art in 1928.

During the Weimar years, Erler maintained his practice, producing portraits, landscapes, and decorative works. However, the artistic landscape was changing rapidly. Expressionism, Dada, and New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) represented the avant-garde, often engaging critically with the social and political turmoil of the time. Artists like Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, and George Grosz offered biting critiques of society, a stark contrast to Erler's more traditional and increasingly monumental style.

As the political climate grew more polarized in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Erler's path began to align with the rising National Socialist movement. He painted a portrait of Adolf Hitler as early as 1931. Sources suggest this early portrait generated some controversy and that Hitler himself may not have been entirely pleased with it. Nevertheless, it signalled Erler's willingness to engage with the Nazi leader before he came to power.

Art in the Third Reich: Official Recognition and Controversy

With the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, the cultural landscape in Germany underwent a radical transformation. The regime actively promoted art that aligned with its ideology – realistic, heroic, often depicting themes of nation, family, labour, and struggle – while brutally suppressing modern art movements, which they condemned as "degenerate" (entartet). Artists associated with Expressionism (like Emil Nolde, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner), Cubism, Dada, Surrealism, and abstraction faced persecution, dismissal from teaching positions, bans on exhibiting or working, and confiscation of their art.

Fritz Erler, whose style had evolved towards a form of monumental realism, found favour with the new regime. His established reputation, technical skill, and nationalistic credentials from the First World War made him an acceptable, even desirable, figure for the Nazis. He became one of the most prominent painters of the Third Reich, receiving numerous official commissions and accolades. He painted further portraits of Hitler, including one exhibited prominently at the Great German Art Exhibition (Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung) in Munich in 1939, which reportedly sold for a substantial sum. He also painted portraits of other high-ranking Nazi officials.

His work was regularly featured in the Great German Art Exhibitions, held annually from 1937 in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst (House of German Art) in Munich. These exhibitions were intended to showcase the officially sanctioned art of the Third Reich, standing in direct opposition to the infamous "Degenerate Art" exhibition held concurrently in 1937. Erler was considered one of the regime's favoured artists, alongside sculptors like Arno Breker and Josef Thorak, and painters like Adolf Ziegler (who ironically was tasked with purging "degenerate" art from German museums). In 1944, posthumously, Erler was included on the "Gottbegnadeten list" (God-gifted list), a roster compiled by Joseph Goebbels and Hitler of artists deemed crucial to Nazi culture.

Erler's art during this period largely conformed to the expectations of the regime: technically proficient, realistic depictions often imbued with a sense of grandeur or heroism, whether in portraits or thematic compositions. While avoiding the overt avant-garde experimentation condemned by the Nazis, his work from this era remains deeply problematic due to its association with and service to a totalitarian and criminal regime. He received the Hesse State Prize for Outstanding Painting in 1935, further cementing his status within the Nazi cultural establishment.

Style Evolution and Influences Revisited

Tracing Fritz Erler's stylistic development reveals a journey through several key phases of German art. His early work shows the imprint of academic training blended with the decorative linearity and symbolic interests of Jugendstil, clearly visible in his contributions to Jugend magazine. The influence of Giovanni Segantini's Divisionist technique and Symbolist leanings added a distinct texture and luminosity to his paintings, particularly landscapes and allegorical scenes.

His involvement with 'Die Scholle' situated him within a group that valued solid craftsmanship and often depicted scenes of Bavarian life and landscape with a decorative, sometimes impressionistic touch, moving away from strict academicism but remaining largely representational. Key figures from this group, like Leo Putz or Adolf Münzer, shared a similar inclination towards colourful, painterly surfaces.

The First World War prompted a shift towards a starker, more monumental realism, particularly suited to the demands of propaganda. Heroic figures, dramatic compositions, and a focus on nationalistic themes became dominant. This monumental tendency continued after the war and found resonance with the aesthetic preferences of the Nazi regime. His later work, especially the official portraits and allegorical pieces produced during the Third Reich, solidified this realistic, often idealized style, emphasizing technical polish and clear representation over subjective expression or formal experimentation. While influenced by Impressionism and Symbolism early on, his path diverged significantly from the trajectory of modernism pursued by artists like the Brücke group (Kirchner, Nolde) or the Blue Rider group (Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc), whose work was later vilified by the regime Erler served. One might also see parallels in the monumental figurative traditions of artists like Ferdinand Hodler or Arnold Böcklin, whose influence permeated German-speaking art circles around the turn of the century.

Legacy, Collections, and Auctions

Fritz Erler died in Munich in 1940, at the height of his official recognition within the Third Reich but before the regime's ultimate collapse. His death spared him from personally facing the consequences of the post-war denazification process. However, his close association with the Nazi regime inevitably casts a long shadow over his legacy. Much of the art produced under Nazi patronage, including works by Erler, was confiscated by the Allies after the war. Some pieces were later returned to German museums, while others remain in storage or in collections outside Germany.

Today, works by Fritz Erler are held in several major German museums. The Deutsches Historisches Museum (German Historical Museum) in Berlin holds important examples of his WWI work, including paintings like Soldat (1917) and posters. The Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich houses works from his earlier period, such as Schwarzer Pierrot. The Museum Wiesbaden, which holds his frescoes in the Kurhaus, has also collected and exhibited his paintings, including works like Der Compagnieführer and Kämpfer vor Verdun. The Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (Berlin State Museums) also hold works by him.

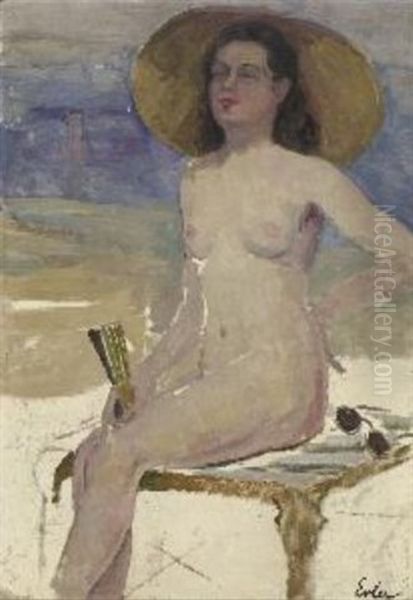

His works occasionally appear on the art market. Auction records indicate sales of paintings like Weiblicher Akt (Female Nude) and Mont Saint Michel in the 2010s, fetching modest prices, suggesting a continued, if perhaps specialized, interest among collectors. However, the market for works closely associated with the Third Reich, particularly official portraits, remains complex and often restricted.

Conclusion: An Artist of Skill and Controversy

Fritz Erler was undoubtedly a highly skilled and versatile artist who played a significant role in the German art world for over four decades. From his contributions to the influential Jugend magazine and the founding of 'Die Scholle' to his impactful WWI propaganda and his prominent position under the Third Reich, his career mirrored the dramatic shifts in German society and culture. He mastered various media, excelling in painting, graphic design, and large-scale decoration.

His artistic journey reflects a transition from the decorative impulses of Jugendstil and the influence of Symbolism towards a monumental realism that served both wartime nationalism and the ideological demands of the Nazi regime. While his technical abilities are undeniable, and his earlier works hold a secure place within the history of German art around 1900, his later career is inseparable from the political context in which it flourished. Evaluating Fritz Erler requires acknowledging his artistic achievements while critically examining his role as a favoured artist of a regime responsible for unprecedented atrocities. He remains a compelling case study of the complex relationship between art, artists, and political power in the 20th century.