Nina Osipovna Kogan stands as a significant, though sometimes overlooked, figure within the revolutionary fervor of the Russian avant-garde in the early twentieth century. Born in 1887 in Saint Petersburg into a family of means and culture, her trajectory as an artist placed her at the heart of Suprematism, one of the most radical and influential abstract art movements. Her close associations with luminaries such as Kazimir Malevich and Marc Chagall, and her active role in the groundbreaking UNOVIS group, underscore her commitment to forging a new artistic language for a new era. Kogan's work, characterized by its geometric purity and dynamic compositions, not only embodied the core tenets of Suprematism but also extended its principles into diverse fields, including applied arts and theatrical design.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Nina Osipovna Kogan was born on March 25 (April 9, according to the new style calendar), 1887, in Vitebsk, not St. Petersburg as some sources suggest, though her upbringing was certainly within an educated and relatively privileged milieu. Her father, Osip Kogan, was a military doctor, a respected profession that afforded the family a degree of social standing. Her mother was reportedly a student of the exclusive St. Catherine's Institute, indicating a background that valued education and cultural refinement. This environment likely provided Kogan with an early exposure to arts and letters, fostering the intellectual curiosity that would later draw her to the radical experiments of the avant-garde.

Details about her early artistic training are somewhat scarce, a common issue for many female artists of the period whose careers were often less meticulously documented than their male counterparts. However, it is clear that by the late 1910s, she was actively pursuing an artistic path that would lead her to become an integral part of the revolutionary art scene burgeoning in Russia, particularly in the vibrant artistic center of Vitebsk.

Vitebsk: A Crucible of Avant-Garde Art

The city of Vitebsk, in present-day Belarus, became an unexpected epicenter for avant-garde art following the Russian Revolution. Marc Chagall, a native of Vitebsk, was appointed Commissar of Arts for the Vitebsk region in 1918 and founded the Vitebsk People's Art School. He invited many progressive artists to teach and work there, transforming the provincial city into a dynamic hub of artistic innovation. Among those who answered the call was Nina Kogan.

Kogan's arrival in Vitebsk and her involvement with the school marked a pivotal moment in her career. Initially, the school was a place of diverse artistic exploration, with figures like Chagall himself, Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, and later El Lissitzky contributing to a lively, if sometimes ideologically varied, atmosphere. Kogan was part of this exciting milieu, absorbing the influences and participating in the debates that shaped the future of art.

The most decisive influence on Kogan's artistic development, however, came with the arrival of Kazimir Malevich in Vitebsk in November 1919. Malevich, the founder of Suprematism, brought with him a fully formed artistic philosophy that advocated for pure artistic feeling, or "supremacy of pure artistic feeling," rather than visual depiction of objects. His vision was uncompromising and quickly gained ascendancy at the Vitebsk school.

UNOVIS and the Supremacy of Pure Form

Under Malevich's charismatic leadership, a group of devoted students and faculty formed UNOVIS (Champions of the New Art; also an acronym for Utverditeli Novogo Iskusstva). Nina Kogan was a key and committed member of this collective from its inception. UNOVIS was more than just an art group; it was a quasi-communist collective, a "party" dedicated to the principles of Suprematism and its application to all aspects of life. They aimed to create a new visual culture that would reflect and shape the new socialist society.

As a member of UNOVIS, Kogan participated in collective projects, exhibitions, and the dissemination of Suprematist ideas. The group's activities were diverse, ranging from painting and graphic design to architectural models, stage designs, and even the decoration of public spaces and propaganda trains. Kogan's involvement was significant; she was not merely a student but an active contributor to the group's creative output and theoretical discussions. She worked alongside other prominent UNOVIS members such as El Lissitzky, Vera Ermolaeva, Lazar Khidekel, and Ilya Chashnik, all of whom were dedicated to Malevich's vision.

The philosophy of Suprematism, with its emphasis on fundamental geometric forms (squares, circles, lines, rectangles), a limited range of colors, and the sensation of floating, non-objective forms in space, profoundly shaped Kogan's artistic language. Her works from this period demonstrate a deep understanding and personal interpretation of these principles.

Key Works and Artistic Style

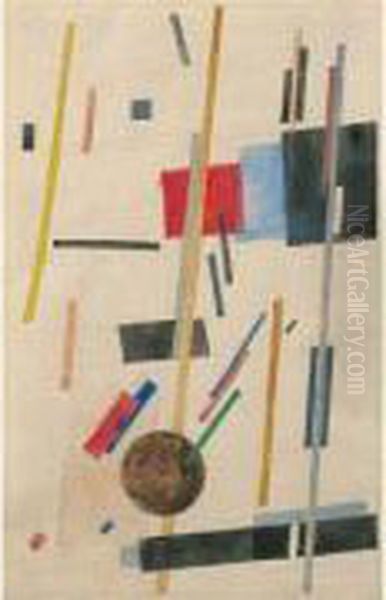

Nina Kogan's artistic style is intrinsically linked to Suprematism. Her compositions are characterized by a dynamic interplay of geometric shapes, often rendered with a clarity and precision that speaks to the movement's pursuit of pure form. While adhering to the core tenets of Suprematism, Kogan's work often possesses a subtle lyricism and a sophisticated sense of balance.

One of her notable areas of exploration was the Suprematist Composition. An example often cited is a work titled Composition from 1925, a watercolor measuring 40x33 cm. Such pieces typically feature an arrangement of colored geometric elements—planes, lines, and basic shapes—that seem to float or move across the picture plane, creating a sense of spatial depth and dynamism without resorting to traditional perspective. These compositions aimed to evoke pure artistic feeling, unburdened by the representation of the material world. Her use of color, while often adhering to the Suprematist palette of black, white, red, and sometimes blue or yellow, could also explore more nuanced tonal relationships.

Kogan also created a series of abstract geometric chessboards, completed around 1929. These works were reportedly featured in the Supremus journal, a publication planned by Malevich and his circle (though only one issue was fully prepared but not published in their time). Designing chessboards was a characteristic avant-garde endeavor, transforming a functional object into a work of art that embodied modern aesthetic principles. For Suprematists, even a game like chess could be re-envisioned through the lens of pure geometric abstraction, reflecting the movement's ambition to permeate all aspects of life with the new art.

Her creation of Suprematist decorative panels further illustrates this aim. These panels were likely intended for interior spaces or as part of larger decorative schemes, demonstrating how Suprematism could be applied to design and architecture. The abstract language of Suprematism was seen as universal, capable of harmonizing spaces and creating a new aesthetic environment.

Contributions to Theatrical Design and Applied Arts

The Russian avant-garde, and UNOVIS in particular, placed great emphasis on the synthesis of arts and the creation of a total work of art (Gesamtkunstwerk). Theatre was a prime arena for such experiments, offering opportunities to combine visual art, movement, sound, and text in new and revolutionary ways. Nina Kogan made significant contributions in this domain.

She is credited with designing the stage set for a Suprematist ballet. This design was featured in the UNOVIS No.1 Almanac (1920), a crucial document of the group's activities and theories. While the specific ballet might be the futurist opera Victory Over the Sun (for which Malevich famously designed sets in 1913, and which UNOVIS restaged or re-envisioned), or another similar experimental production, Kogan's involvement highlights her role in translating Suprematist principles into three-dimensional space and performance. Such designs would have emphasized geometric forms, dynamic spatial relationships, and a non-representational aesthetic, aiming to create an environment that itself was an active participant in the performance. This aligns with the work of other avant-garde women artists deeply involved in stage design, such as Alexandra Exter, Lyubov Popova, and Varvara Stepanova.

Kogan also designed Suprematist streetcar advertisement paintings in 1920. This endeavor reflects UNOVIS's commitment to taking art out of the studio and into the streets, making it part of everyday life and public experience. These mobile artworks would have transformed mundane city transport into dynamic displays of the new art, serving both aesthetic and propagandistic functions.

Furthermore, Kogan is noted for creating a toy named "Kha Bo-Ro," reportedly inspired by a design from the Futurist poet and artist Alexander Kruchenykh. This foray into toy design is fascinating, as it connects with the avant-garde's interest in childhood, pedagogy, and the idea that new forms of art and design could shape new ways of thinking from an early age. Artists like Vladimir Tatlin and Alexander Rodchenko also explored design for children, believing that abstract forms could stimulate creativity and imagination.

Later Years and the Shifting Artistic Climate

The period of intense experimentation and utopian fervor of the early Russian avant-garde was relatively short-lived. By the mid-1920s, the political and cultural climate in the Soviet Union began to shift. The state started to favor more accessible, realistic art forms that could directly serve its ideological purposes. Malevich left Vitebsk in 1922 for Petrograd (Leningrad), and UNOVIS effectively dissolved, though its members continued to work and develop its ideas.

Information about Nina Kogan's activities in the later 1920s and 1930s becomes more fragmented. Like many avant-garde artists, she faced an increasingly challenging environment. The rise of Socialist Realism as the officially sanctioned artistic doctrine in the 1930s marginalized abstract and experimental art. Artists who did not conform often faced persecution, were denied opportunities to exhibit or work, or were forced into more "acceptable" fields like illustration or textile design.

Nina Osipovna Kogan passed away in 1942, likely in Leningrad (formerly St. Petersburg). The circumstances of her death, occurring during the tumultuous war years and the Siege of Leningrad, are not widely documented. Her passing marked the end of a life dedicated to artistic innovation, a life that had witnessed and participated in one of the most radical transformations in the history of art.

Legacy and Rediscovery

For many decades, the contributions of Nina Kogan, like those of many other Russian avant-garde artists, particularly women, were largely obscured, both within the Soviet Union and internationally. The official suppression of non-figurative art meant that their work was rarely exhibited or studied. However, from the 1960s onwards, there has been a gradual rediscovery and re-evaluation of the Russian avant-garde.

Kogan's works have appeared in exhibitions and auctions, and her role within UNOVIS and the broader Suprematist movement is increasingly acknowledged by art historians. Her paintings, watercolors, and designs are valued for their intrinsic artistic quality and as important documents of a pivotal period in art history. Her works can be found in various collections, and pieces attributed to her have been sold at auction houses like Accademia Fine Art in Monte Carlo.

However, the rediscovery of Russian avant-garde art has also been complicated by the issue of forgeries. The high market value of works by artists from this period, coupled with historical obscurities and lost provenances, has unfortunately led to the circulation of fakes. This necessitates careful scholarly research and connoisseurship when assessing works attributed to Kogan and her contemporaries like Ivan Kliun, Olga Rozanova, or Nadezhda Udaltsova.

Kogan in the Constellation of the Avant-Garde

Nina Kogan's significance lies not only in her individual artistic production but also in her active participation in a collective revolutionary movement. She was one of the dedicated "affirmers of the new art" who worked alongside Malevich to realize the ambitious vision of Suprematism. Her commitment to applying Suprematist principles across various media—from easel painting to stage design and utilitarian objects—reflects the holistic and transformative aspirations of the movement.

She was part of a remarkable generation of artists in Russia who sought to break entirely with past artistic traditions. While Malevich was the towering figure of Suprematism, and artists like El Lissitzky (with his Prouns) and Vladimir Tatlin (with Constructivism) forged distinct but related paths, Kogan's contributions were vital to the fabric and dissemination of these new ideas. She shared with artists like Lyubov Popova and Varvara Stepanova a versatility that moved between "high art" and applied design, challenging traditional hierarchies.

The Russian avant-garde was also notable for the prominent role played by women artists. Kogan, alongside Vera Ermolaeva, Olga Rozanova, Natalia Goncharova, Alexandra Exter, Lyubov Popova, Varvara Stepanova, and Nadezhda Udaltsova, formed a powerful contingent of innovators who were central to the development of Cubo-Futurism, Rayonism, Suprematism, and Constructivism. Kogan's story is an essential part of this broader narrative of women artists at the forefront of radical artistic change. Even if her name is not as widely recognized as Wassily Kandinsky or Mikhail Larionov, her dedication to the Suprematist cause was unwavering.

Conclusion

Nina Osipovna Kogan was a dedicated and talented artist who played an important role in the development and practice of Suprematism. From her formative years to her intense involvement with Malevich and UNOVIS in Vitebsk, she embraced the revolutionary potential of abstract art. Her works, whether paintings, designs for the stage, or applied arts, consistently reflect the core principles of Suprematism: the pursuit of pure artistic feeling through non-objective geometric form.

While the utopian dreams of the early Russian avant-garde eventually collided with harsh political realities, the art produced during this period, including the contributions of Nina Kogan, remains a testament to a moment of extraordinary creative energy and radical vision. Her legacy, though deserving of further research and wider recognition, is secured as a vital participant in one of the twentieth century's most daring artistic enterprises, an artist who helped to shape the visual language of modernity. Her life and work continue to inspire and offer insights into the transformative power of art in times of profound social change.