Vladimir Davidovich Baranoff-Rossine stands as a unique and compelling figure in the narrative of 20th-century modern art. Born in the Russian Empire, active in the vibrant artistic centers of both Russia and Paris, and tragically lost in the Holocaust, his life and work encapsulate the dynamism, innovation, and turmoil of his era. He was not merely a painter but a multifaceted creator: an avant-garde artist associated primarily with Cubo-Futurism, a sculptor, an inventor driven by synaesthetic curiosity, and even a musician of sorts. His journey took him from the Imperial Academy in St. Petersburg to the bohemian heart of Montparnasse, through the revolutionary fervor of Moscow, and ultimately to a devastating end in Auschwitz. This complex trajectory is reflected in an equally diverse body of work that synthesized major European art movements while retaining a distinct personal vision.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Vladimir Baranoff-Rossine was born Shulim Wolf Leib Baranov on January 1st (or 13th according to the Gregorian calendar), 1888, in Kherson, a city in present-day Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire. He came from a Jewish background, a heritage that would tragically mark his final years. His artistic inclinations emerged early, leading him to pursue formal training. Between 1902 and 1903, he studied in Odessa, a significant cultural hub on the Black Sea, before moving north to the imperial capital.

From 1903 to 1907, Baranoff-Rossine attended the prestigious Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. This institution, while venerable, was largely steeped in academic tradition. Like many aspiring modernists of his generation, Baranoff-Rossine likely found the Academy's conservative approach restrictive. The seeds of rebellion against academic constraints were sown during these years, pushing him towards the burgeoning avant-garde movements that were beginning to challenge established artistic norms across Europe. His time at the Academy, however, provided him with a solid technical foundation upon which he would build his later experiments.

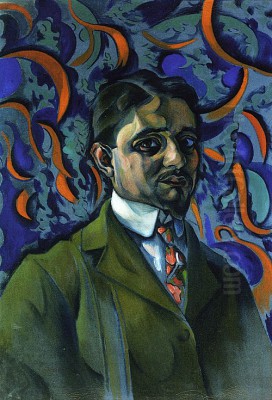

His early works from this period began to show a departure from strict academic realism. He started exploring newer stylistic trends filtering into Russia from Western Europe, particularly Post-Impressionism and Fauvism. An early example hinting at his future direction is the pointillist-influenced Self-portrait with Brush from 1907. This work, while still representational, demonstrates a clear interest in color theory and the optical effects of juxtaposed color dots, techniques associated with Neo-Impressionists like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, but rendered with a bolder, more expressive touch.

Entering the Avant-Garde Arena

Baranoff-Rossine's official entry into the avant-garde scene was significantly boosted by his association with the influential Burliuk brothers, David and Vladimir. David Burliuk, often called the "father of Russian Futurism," was a key organizer and promoter of modernist art in Russia. In 1908, Baranoff-Rossine, alongside the Burliuks, participated in organizing an important avant-garde exhibition titled "Zveno" (The Link) in Kyiv. This event helped establish his reputation among the progressive artistic circles of the Russian Empire.

His friendship with the Burliuks connected him to a network of radical artists and poets who were forging a distinctly Russian version of modernism, often blending Western European innovations with native folk traditions and contemporary themes. This milieu included figures like Natalia Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov, Kazimir Malevich, and Alexandra Exter. Baranoff-Rossine absorbed these influences, contributing to the vibrant, experimental atmosphere of the pre-revolutionary Russian art scene.

His work during this period began to show a decisive move towards Cubism and Futurism. He was among the earliest Russian artists to engage deeply with Cubist principles, likely encountering the works of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque through reproductions or exhibitions. He combined the fragmented perspectives and geometric forms of Cubism with the dynamic energy, celebration of motion, and vibrant color palettes associated with Italian Futurism (led by artists like Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla) and French Orphism (pioneered by Robert Delaunay and Sonia Delaunay). This fusion became known as Cubo-Futurism, a defining movement of the Russian avant-garde, and Baranoff-Rossine was one of its notable practitioners.

The Parisian Crucible: La Ruche and Cubo-Futurism

Around 1910, seeking direct exposure to the epicenter of modern art, Baranoff-Rossine moved to Paris. He settled in the famous artists' residence known as "La Ruche" (The Beehive) in Montparnasse. This dilapidated, circular structure housed a diverse community of international artists, many of them émigrés from Eastern Europe, often living in poverty but rich in creative energy. Here, he rubbed shoulders with fellow residents who would become giants of modern art, including Marc Chagall, Chaim Soutine, Amedeo Modigliani, Alexander Archipenko, and Ossip Zadkine.

This Parisian period was crucial for Baranoff-Rossine's artistic development. He was immersed in the latest developments, directly engaging with Cubism, Fauvism (personified by Henri Matisse), and the burgeoning abstract tendencies of Orphism. He exhibited his work in Parisian salons, including the Salon des Indépendants, gaining recognition within the international avant-garde community. His style solidified, characterized by dynamic compositions, fractured forms, and a bold, often non-naturalistic use of color, reflecting the Orphist interest in the simultaneous contrast of colors to create rhythm and form.

Works from this period, such as the Still Life with Fruit and Flowers (c. 1910-1915), exemplify his mature Cubo-Futurist style. These paintings feature fragmented objects viewed from multiple angles, energetic diagonal lines suggesting movement, and a vibrant palette that goes beyond mere description to evoke sensation and emotion. He also began experimenting with sculpture, translating his Cubo-Futurist principles into three dimensions, creating dynamic assemblages from various materials. His sculptures from this era, like Symphony No. 1 (1913), are considered pioneering examples of modern sculpture, comparable to the works of Archipenko and Jacques Lipchitz.

Return to Russia: Revolution and Artistic Experimentation

The outbreak of World War I prompted Baranoff-Rossine to leave Paris. He traveled, exhibiting his work, notably holding a solo exhibition in Oslo, Norway, in 1916. By 1917, the year of the Russian Revolution, he was back in Russia, initially in Petrograd (St. Petersburg). He engaged with the transformed artistic landscape, participating in exhibitions organized by groups like Mir Iskusstva (World of Art), which had evolved from its Symbolist origins to embrace newer trends.

The revolutionary period initially fostered a climate of radical artistic experimentation, with the avant-garde playing a significant role in shaping the new culture. Baranoff-Rossine contributed to this atmosphere. In 1918, he exhibited in Moscow. By 1922, he was appointed as a teacher at the Higher Art and Technical Studios (Vkhutemas) in Moscow, a groundbreaking institution often compared to the German Bauhaus. Vkhutemas aimed to integrate art, craft, and industrial design, and its faculty included leading avant-garde figures like Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, Alexander Rodchenko, Liubov Popova, and Varvara Stepanova.

His involvement with Vkhutemas placed him at the heart of Constructivist and Productivist debates about the role of the artist in the new socialist society. While contributing to the pedagogical mission, Baranoff-Rossine continued his personal artistic explorations, which increasingly involved not just painting and sculpture but also technological invention, particularly related to the synthesis of the arts.

The Inventor: Synaesthesia and the Optophonic Piano

One of Baranoff-Rossine's most fascinating and unique contributions lies in his invention of the "Optophonic Piano" (also referred to as the Color Piano or Optophone). Driven by an interest in synaesthesia – the neurological phenomenon where stimulation of one sensory pathway leads to involuntary experiences in a second pathway (like seeing colors when hearing sounds) – he sought to create an instrument that could produce a unified experience of music and visual art.

The Optophonic Piano was a complex device. When keys were played, it not only produced musical tones but also projected corresponding colored lights and patterns onto a screen. The system involved rotating painted discs or filters illuminated from behind, synchronized with the keyboard. Baranoff-Rossine gave public demonstrations of his invention, including one at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow in 1924, performing works by composers like Alexander Scriabin, who himself had explored color-music theories.

This invention placed Baranoff-Rossine in a lineage of artists and inventors fascinated by the potential fusion of sound and image, dating back centuries but gaining particular traction in the early 20th century with figures like Scriabin and the abstract painter Wassily Kandinsky, whose theories emphasized the spiritual and emotional correspondences between colors and sounds. The Optophonic Piano was a pioneering effort in kinetic art and multimedia performance, anticipating later developments in light shows and visual music.

Return to Paris: Later Career and Stylistic Evolution

By 1925, the artistic climate in the Soviet Union was becoming increasingly restrictive, with Socialist Realism gradually being enforced as the official style. Like many avant-garde artists who found their experimental work falling out of favor, Baranoff-Rossine chose to emigrate. He returned to Paris, the city that had been so formative for him earlier. He would remain in France for the rest of his life.

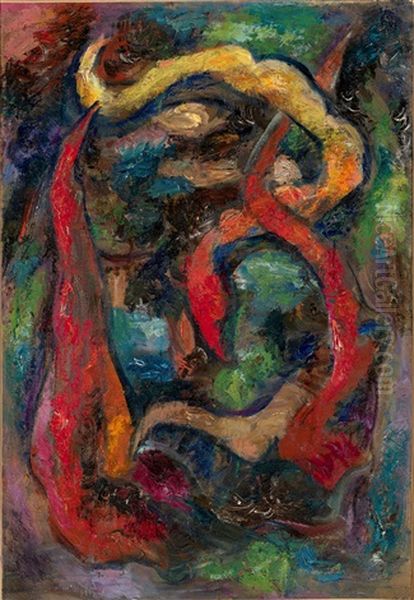

In Paris, he continued to paint, sculpt, and refine his inventions. His artistic style continued to evolve. While retaining elements of his Cubo-Futurist past, his work in the late 1920s and 1930s showed influences from Surrealism, which was then a dominant force in the Parisian art world led by André Breton. He explored biomorphic abstraction, creating fluid, organic forms in both painting and sculpture. His palette sometimes became more subdued, though his interest in dynamic composition and structural innovation remained.

A notable work from this later period is the Polytechnic Sculpture (also known as Polychrome Sculpture) from around 1933. This piece combines disparate elements, possibly including found objects, into an abstract assemblage characterized by contrasting textures and shapes, reflecting both Constructivist principles and Surrealist juxtapositions. He also continued to work on his Optophonic Piano and explored other inventions, including military camouflage techniques (the "Chameleon Method") and a machine for producing and measuring gemstones (the "Photosher").

Artistic Style Revisited: A Synthesis of Modernisms

Throughout his career, Baranoff-Rossine's art was characterized by synthesis. He rarely adhered strictly to a single movement but instead drew elements from various sources to create his own visual language. His core style, Cubo-Futurism, merged the analytical deconstruction of form found in the Cubism of Picasso and Braque with the dynamism, speed, and vibrant color celebrated by Italian Futurists and the color theories of French Orphists like Robert and Sonia Delaunay.

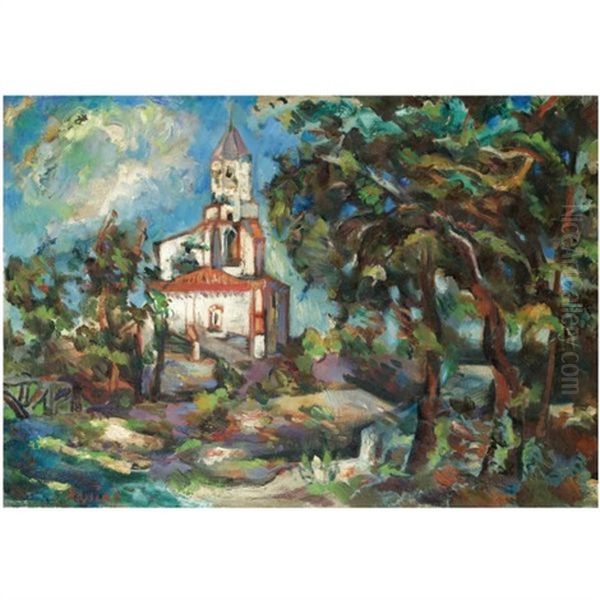

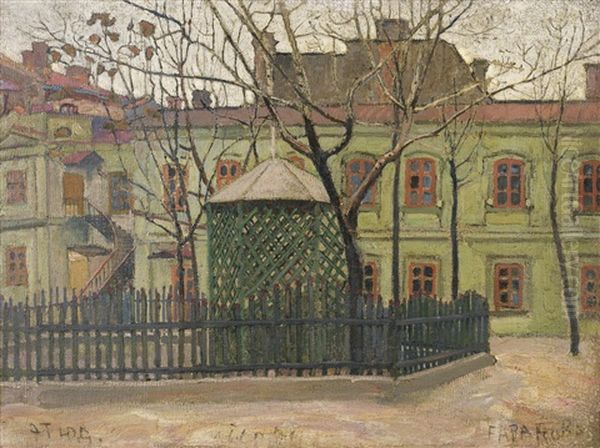

His paintings often feature a kaleidoscopic fragmentation of reality. Objects and figures are broken down into geometric planes and facets, viewed simultaneously from multiple viewpoints. Unlike the often monochromatic palette of early Analytic Cubism, Baranoff-Rossine employed rich, saturated colors, using them not just descriptively but structurally and emotionally, creating rhythm and depth through chromatic contrasts, much like the Delaunays. Works like The Church or The Green House on the Square showcase this approach, transforming architectural motifs into vibrant, dynamic compositions of color and form.

Later, his engagement with Surrealism introduced more organic, flowing shapes and dreamlike juxtapositions, though often still structured with a Cubist-derived sense of composition. His sculptures similarly evolved from the sharp, angular forms of his early Cubo-Futurist pieces to more rounded, biomorphic abstractions later on, sometimes incorporating diverse materials in the spirit of Constructivist assemblage or Surrealist object art (akin to works by Jean Arp or Max Ernst). His enduring interest in light, color, and motion remained a constant thread, linking his painting, sculpture, and inventions.

Network and Influence: Bridging East and West

Baranoff-Rossine occupied a significant position within the international network of avant-garde artists. His early connections with the Burliuk brothers placed him firmly within the Russian Futurist movement. His time at La Ruche integrated him into the heart of the École de Paris, connecting him with Chagall, Soutine, Modigliani, Archipenko, Zadkine, and others who formed a crucial bridge between Eastern European traditions and Parisian modernism.

He actively participated in the exhibition culture of his time, showing his work in St. Petersburg, Kyiv, Moscow, Oslo, and Paris. His involvement with groups like Mir Iskusstva and his teaching role at Vkhutemas further solidified his standing within the Russian avant-garde. His later life in Paris kept him connected to the ongoing developments in European art.

His work, particularly his synaesthetic experiments with the Optophonic Piano, positioned him as an innovator exploring the boundaries between different art forms. While perhaps less famous today than some of his contemporaries like Kandinsky or Malevich, his contributions were recognized during his lifetime. His ideas about light and color in motion found parallels in the work of other experimenters, such as the Russian artist Grigory Gidoni, who also explored kinetic light art. Baranoff-Rossine's career exemplifies the cross-cultural fertilization that characterized early 20th-century modernism, absorbing influences from multiple sources and contributing to the shared language of the avant-garde.

Persecution and Tragic End in the Holocaust

The final chapter of Vladimir Baranoff-Rossine's life is marked by the tragedy of the Holocaust. Living in occupied France during World War II, his Jewish heritage placed him in grave danger under the anti-Semitic policies of the Nazi regime and the collaborating Vichy government. Despite his contributions to art and invention, he was targeted for persecution.

In late 1943 (sources vary slightly on the exact date, sometimes citing 1942), Baranoff-Rossine was arrested and deported from France. He was sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp in German-occupied Poland. There, in January 1944, Vladimir Baranoff-Rossine was murdered, one of the millions of victims of the Nazi genocide. His death cut short a life dedicated to artistic innovation and experimentation. He shares this tragic fate with other artists persecuted and killed during the Holocaust, such as Felix Nussbaum and Otto Freundlich, reminding us of the devastating human cost of intolerance and hatred.

Legacy, Collections, and Market Presence

Despite his premature death, Vladimir Baranoff-Rossine left behind a significant body of work that continues to be recognized for its innovation and historical importance. His paintings, sculptures, and drawings are held in the collections of major international museums, testifying to his enduring significance. Prominent institutions housing his work include the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, the Musée National d'Art Moderne (Centre Pompidou) and the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in Paris, and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York.

His work periodically appears at auction, sometimes achieving significant prices. For instance, his Still Life with Fruit and Flowers was offered at Christie's London in 2013 with a substantial estimate. In 2021, another painting reportedly sold for $326,000. However, the market for his work can be inconsistent, with reports suggesting a variable sell-through rate at auctions over the past decade.

Intriguingly, Baranoff-Rossine's legacy has also entered the digital age. In 2021, his family estate partnered with the NFT (Non-Fungible Token) platform Mintable to auction digital versions of his works, including the 1926 Abstract Composition. This initiative aimed to introduce his art to a new generation and explore contemporary avenues for artistic dissemination, demonstrating the ongoing relevance and adaptability of his creative legacy. His Optophonic Piano, while perhaps not fully realized in his lifetime, remains a fascinating historical example of early multimedia art.

Conclusion: An Enduring Avant-Garde Spirit

Vladimir Baranoff-Rossine was an artist whose life and work embodied the restless spirit of the early 20th-century avant-garde. His journey across geographical and artistic boundaries – from Ukraine and Russia to France, from Pointillism through Cubo-Futurism to Surrealist-tinged abstraction – resulted in a rich and varied oeuvre. He was a synthesizer, adept at absorbing and transforming the major artistic currents of his time into a personal vision characterized by dynamic energy, bold color, and structural innovation.

Beyond his contributions as a painter and sculptor, his inventive pursuits, particularly the Optophonic Piano, highlight a forward-looking interest in technology and the potential for inter-sensory artistic experiences. He stood at the crossroads of cultures and disciplines, a testament to the interconnectedness of the modern world and its art. Though his life was tragically cut short by the horrors of the Holocaust, Vladimir Baranoff-Rossine's work endures, securing his place as a significant, multifaceted figure in the history of modern art and invention. His legacy continues to resonate, reminding us of the power of creativity even in the face of profound adversity.