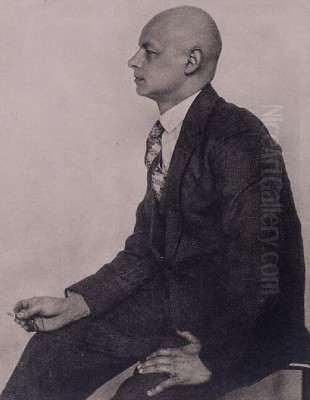

Oskar Schlemmer stands as a pivotal figure in twentieth-century art, a German polymath whose creative energies flowed through painting, sculpture, choreography, and stage design. Born on September 4, 1888, in Stuttgart, and passing away in Baden-Baden on April 13, 1943, Schlemmer's life and career were deeply intertwined with the tumultuous history of modern Europe and the groundbreaking innovations of the Bauhaus school. He dedicated his artistic life to exploring the fundamental relationship between the human figure and the space it occupies, translating his philosophical inquiries into visually striking, often abstract forms that continue to resonate today.

Schlemmer's vision was holistic, seeking a synthesis of the arts – a Gesamtkunstwerk or total work of art – where disciplines merged to express a unified understanding of modern existence. His work is characterized by a unique blend of geometric precision, a fascination with mechanics and movement, and a profound, almost metaphysical contemplation of humanity's place within the cosmos and the rapidly changing technological landscape of his time.

Early Formation and Artistic Awakening

Schlemmer's artistic journey began in his hometown of Stuttgart, where he attended the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts) and later the Akademie der Bildenden Künste (Academy of Fine Arts). During these formative years, he studied under influential figures like the landscape painter Christian Landenberger and, significantly, the abstract pioneer Adolf Hölzel. Hölzel's progressive teaching methods and emphasis on formal experimentation profoundly impacted Schlemmer's developing style.

It was also in Stuttgart that Schlemmer forged crucial early relationships with fellow artists who would become lifelong friends and collaborators. He developed close ties with Willi Baumeister and Otto Meyer-Amden. This period saw Schlemmer grappling with various contemporary influences, absorbing elements from Cubism and Futurism, but always filtering them through his unique sensibility focused on the human form.

His studies were interrupted by World War I, an experience that undoubtedly shaped his worldview. After the war, Schlemmer returned to Stuttgart, eager to participate in the artistic reconstruction of society. He became involved in efforts to reform art education, reflecting a growing belief in art's social potential. A notable incident occurred in 1918 when disagreements over teaching methods, partly fueled by Schlemmer's advocacy for change, led to his former mentor Hölzel's resignation from the Stuttgart Academy. Schlemmer even attempted, unsuccessfully, to persuade the visionary artist Paul Klee to take up the vacant position. Together with Baumeister and others, Schlemmer founded the Üecht group (possibly referencing a dialect word for "genuine" or "real"), aiming to foster artistic innovation and social engagement in the post-war era.

The Bauhaus Years: A Crucible of Innovation

The most defining chapter of Oskar Schlemmer's career began in 1920 (some sources say late 1919 or 1921, but 1920 is commonly cited for his active start) when Walter Gropius, the founder of the Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar, invited him to join the faculty. This appointment marked a significant turning point, placing Schlemmer at the heart of the most influential design school of the twentieth century. The Bauhaus aimed to break down the traditional barriers between fine arts, crafts, and industrial design, fostering a collaborative environment where creativity could flourish across disciplines.

Schlemmer thrived in this interdisciplinary atmosphere. He initially headed the workshop for stone sculpture and later wood sculpture. However, his most significant and lasting contribution at the Bauhaus was his leadership of the Stage Workshop (Bühnenwerkstatt), a position he assumed around 1923. This role allowed him to fully explore his ideas about the human figure in motion and its relationship to architectural space.

At the Bauhaus, Schlemmer worked alongside some of the era's most brilliant artistic minds. His colleagues included painters like Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee (who eventually joined the Bauhaus faculty), and Lyonel Feininger, the theorist and educator Johannes Itten, and the versatile designer László Moholy-Nagy. This concentration of talent created a dynamic and often challenging environment that pushed Schlemmer to refine his artistic and pedagogical concepts. He became a central figure in shaping the school's identity and curriculum.

The Human Figure as Measure

Central to Schlemmer's entire artistic output was his profound and continuous investigation of the human figure – "Man" (Der Mensch). He saw the figure not merely as a subject for representation but as a fundamental measure, a point of intersection between the natural and the artificial, the organic and the geometric, the individual and the universal law. He sought to understand the mathematical and mechanical laws governing human form and movement, viewing the body as a kind of architecture in motion.

This exploration led him to develop a highly stylized and abstracted representation of the human form. Figures in his paintings and designs often appear simplified into geometric components – spheres, cylinders, cones – resembling mannequins, puppets, or automatons. This was not intended to dehumanize, but rather to universalize the figure, stripping away individual peculiarities to reveal underlying structures and relationships with the surrounding space. He saw the figure as existing within a network of invisible spatial coordinates and forces.

His pedagogical activities at the Bauhaus directly reflected these concerns. Schlemmer developed and taught a highly influential course titled "Der Mensch" (Man). This unique course integrated elements of life drawing, anatomy, philosophy, and even physics, encouraging students to analyze the human form from multiple perspectives – biological, psychological, and metaphysical. His teaching notes, later published, reveal a deep engagement with concepts of proportion, movement, and the figure's symbolic resonance within the larger cosmic order. He connected the human form to architecture, technology, and social processes, reflecting the Bauhaus ideal of unifying art, life, and technology.

The Triadic Ballet: A Revolution on Stage

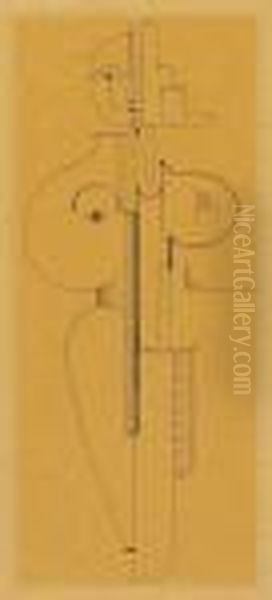

Oskar Schlemmer's most famous and arguably most revolutionary work is Das Triadische Ballett (The Triadic Ballet). Premiering in Stuttgart in 1922 after years of development, it represents the culmination of his ideas about the figure, space, costume, and movement. The ballet is structured around the number three ("triadic"), featuring three acts, three dancers (originally two female, one male), twelve dances, and eighteen costumes. It fundamentally broke with traditional ballet conventions.

The Triadic Ballet was less a narrative dance and more a moving sculpture, a "ballet of forms." Schlemmer designed extraordinary costumes that transformed the dancers into abstract, geometric sculptures. These costumes, often bulky and restrictive, dictated the dancers' movements, turning them into living marionettes navigating a mathematically defined space. Made from materials like papier-mâché, wood, and padded fabric, the costumes represented archetypal forms – the spiral, the sphere, the cone, the wire frame – exploring different spatial dynamics. His brother, Carl "Casca" Schlemmer, a skilled craftsman, played a crucial role in constructing these complex costume-sculptures based on Oskar's designs.

The choreography itself was stylized and anti-naturalistic, emphasizing precise, often jerky or mechanical movements that corresponded to the geometric nature of the costumes and the abstract stage setting. Schlemmer aimed to demonstrate the fundamental laws of bodily movement within space, liberated from psychological expression or narrative storytelling. He described it as a party of form and color, exploring themes of transformation and the relationship between the human body and its artificial extensions.

The Triadic Ballet was groundbreaking. It challenged audiences and critics alike, some praising its radical innovation and visual power, others finding it overly mechanistic and lacking human warmth – a criticism Schlemmer acknowledged but saw as part of his exploration of the modern condition. Despite the mixed initial reception, the ballet became a landmark of avant-garde theatre and dance, profoundly influencing generations of stage designers, choreographers, and even fashion designers. Its visual language continues to inspire artists today, including figures in popular culture like David Bowie and Lady Gaga.

Painting and Sculpture: Exploring Form Beyond the Stage

While the Stage Workshop and the Triadic Ballet were central to his Bauhaus activities, Schlemmer remained a prolific painter and sculptor throughout his career. His two-dimensional works often explored similar themes to his stage designs: the human figure abstracted within architectural or geometric space. His figures are typically depersonalized, rendered with smooth surfaces and simplified contours, emphasizing their formal qualities and spatial relationships.

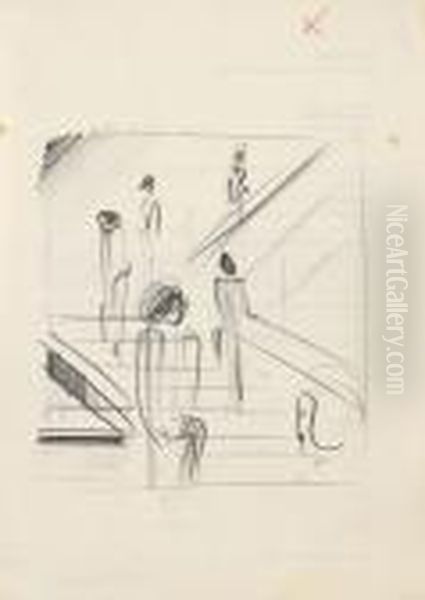

One of his most iconic paintings is Bauhaustreppe (Bauhaus Stairway), created in 1932. It depicts figures ascending the staircase designed by Gropius in the Dessau Bauhaus building. The figures are stylized and almost ethereal, integrated into the clean lines and geometric structure of the architecture. The painting captures the spirit of the Bauhaus – its dynamism, its rationalism, and its focus on human activity within a modern, designed environment. The work later became the subject of ownership disputes but remains a quintessential image associated with Schlemmer and the school.

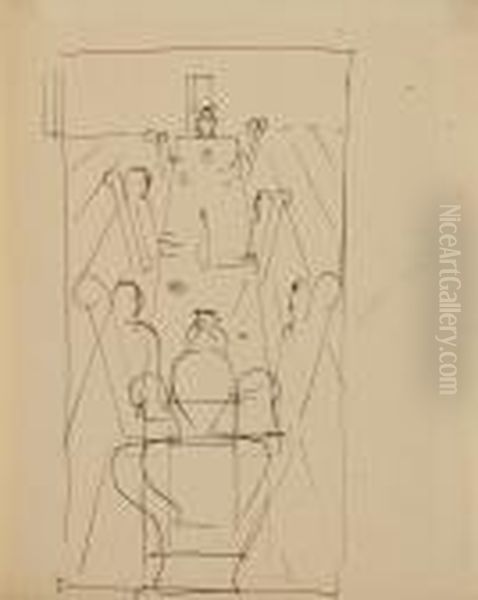

Other significant paintings like Tischgesellschaft (Group at Table) from 1923 and Idealistic Encounter (1928) showcase his characteristic style. Figures are arranged in carefully composed, often symmetrical groupings within shallow, stage-like spaces. Perspective is often flattened or manipulated, and color is used structurally to define form and mood. There's a sense of stillness and contemplation in these works, a quiet monumentality that belies the underlying exploration of movement and spatial dynamics. His palette often employed subtle harmonies and contrasts, contributing to the serene yet intellectually charged atmosphere.

Schlemmer's sculptural work, though less extensive than his painting, also reflects his core concerns. He created freestanding figures and reliefs, often in plaster or metal, that translated his geometric figuration into three dimensions. These works further explored the body's volumes and its interaction with the surrounding void, reinforcing his consistent focus on the interplay between solid form and empty space.

Gesamtkunstwerk and Interdisciplinary Vision

Schlemmer embodied the Bauhaus ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk, the total work of art that integrates multiple disciplines into a unified whole. His work consistently blurred the lines between painting, sculpture, architecture, dance, and costume design. He did not see these as separate fields but as different facets of a single artistic investigation into the nature of form, space, and the human condition in the modern age.

His concept of "Plastik," as he sometimes referred to his multidisciplinary approach, emphasized the sculptural or three-dimensional quality inherent in all art forms, including painting and performance. For Schlemmer, the stage was a laboratory where spatial and formal ideas could be tested dynamically. The dancer's body became a piece of mobile sculpture, the costume an extension of that sculpture, and the stage architecture the defining spatial context.

This interdisciplinary approach was radical for its time and remains a key aspect of his legacy. He demonstrated how different art forms could enrich and inform one another, leading to new possibilities for expression. His work paved the way for later developments in performance art, installation art, and multimedia practices where the integration of diverse elements is paramount. He saw art not just as aesthetic creation but as a form of research into fundamental principles.

Conflict and Persecution: The Nazi Era

Schlemmer's innovative spirit and association with the Bauhaus placed him in direct opposition to the rising tide of National Socialism in Germany. The Nazis viewed the Bauhaus and its associated artists, including Schlemmer, Kandinsky, Klee, and Moholy-Nagy, as proponents of "degenerate art" (Entartete Kunst) – cosmopolitan, intellectual, and fundamentally un-German.

After the Bauhaus was forced to close under political pressure in 1933, Schlemmer faced increasing persecution. He lost his teaching position at the United State Schools for Fine and Applied Arts in Berlin that same year. His works were removed from public collections and included in the infamous "Degenerate Art" exhibition organized by the Nazis in Munich in 1937, intended to ridicule modern art.

Finding it increasingly difficult to work and exhibit, Schlemmer entered a period of "internal emigration." He briefly sought refuge in Switzerland but ultimately returned to Germany. To survive, he was forced to take on work that conflicted with his artistic principles, including designing camouflage patterns for the military and working in a lacquer factory in Wuppertal owned by Kurt Herberts, who secretly employed several avant-garde artists.

During this difficult period, Schlemmer continued to create art, albeit in relative secrecy. His late works, particularly the small-format "Fensterbilder" (Window Pictures) painted while looking out from his factory workspace, possess a more intimate and melancholic quality. These paintings often depict solitary figures or groups viewed through window frames, suggesting themes of confinement, observation, and quiet resilience. They reflect the isolation and psychological pressures of living under a repressive regime while still retaining his characteristic formal elegance.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Despite the hardships of his later years and his relatively early death in 1943 from illness, Oskar Schlemmer's influence on subsequent generations of artists and designers has been profound and multifaceted. His pioneering work in stage design fundamentally altered conceptions of performance space and the role of the body within it. The Triadic Ballet remains a touchstone for experimental theatre, dance, and costume design.

His exploration of the human figure as an abstract, geometric form resonated with later developments in sculpture and painting. Artists working in modes ranging from Constructivism (like contemporaries El Lissitzky or Alexander Rodchenko, though Schlemmer's work had a different, more metaphysical bent) to Minimalism found echoes in his formal rigor and spatial awareness. His integration of art and technology anticipated aspects of kinetic art and digital media.

Schlemmer's pedagogical ideas, particularly the interdisciplinary nature of his "Man" course, contributed significantly to the evolution of modern art education. The Bauhaus model, which he helped shape, continues to influence design schools worldwide. His emphasis on understanding fundamental principles of form, color, and space remains relevant.

In the post-war era, Schlemmer's work was gradually rediscovered and re-evaluated. Major retrospectives helped solidify his position as a key figure of European modernism. Contemporary artists and designers continue to draw inspiration from his work. For instance, designer Eric Roinestad has explicitly referenced Schlemmer's costume designs in his own creations. The visual language Schlemmer developed can be seen reflected, consciously or unconsciously, in fields as diverse as graphic design, architecture, and fashion. Figures like Max Bill, a student deeply influenced by Bauhaus principles, carried forward aspects of this legacy.

Market Recognition

The art market has increasingly recognized Oskar Schlemmer's importance. His major works command significant prices at auction, reflecting both their historical significance and their aesthetic appeal. The 1998 sale of Idealistic Encounter for nearly $1.5 million and the 2023 sale of Tischgesellschaft for approximately $2.9 million (£2.595 million) attest to his high standing. Even smaller works on paper or studies can fetch substantial sums, indicating sustained interest from collectors and institutions. The high value placed on his work underscores his established position within the canon of modern art.

Conclusion: The Harmonious Man in Space

Oskar Schlemmer was more than just a painter, sculptor, or designer; he was a visionary thinker who sought harmony between humanity, art, and the modern world. Through his diverse body of work, he relentlessly explored the essence of the human form and its intricate dance with the space surrounding it. His stylized figures, geometric abstractions, and revolutionary stage concepts were all part of a larger quest to understand and articulate the underlying laws governing existence.

As a central figure at the Bauhaus, he not only contributed significantly to its artistic output but also helped shape its enduring educational philosophy. Though his career was tragically curtailed by political persecution, his legacy endures. Oskar Schlemmer's unique synthesis of formal rigor, theatrical innovation, and philosophical depth continues to inspire and challenge, reminding us of the power of art to investigate the fundamental questions of what it means to be human in space and time.