Albert Müller stands as a significant, albeit tragically short-lived, figure in the landscape of 20th-century European art. A key proponent of Swiss Expressionism, his vibrant and emotionally charged work, created over a brief but intense period, left an indelible mark on the art scene of his time, particularly in his native Basel. His close association with the German Expressionist giant Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and his role in co-founding the influential "Rot-Blau" artists' group further cement his importance. Though his career spanned less than a decade before his untimely death, Müller's artistic output across various media continues to resonate.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on November 29, 1897, in Basel, Switzerland, Albert Müller embarked on his artistic journey within his hometown. His initial training focused on the craft of glass painting, a medium requiring both technical skill and an understanding of light and color. This early experience likely contributed to the luminosity and bold chromatic choices that would later characterize his mature work. Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Müller pursued further studies at the Allgemeine Gewerbeschule (General Trade School) in Basel, immersing himself in the fundamentals of art and design.

During these formative years, Müller, like many aspiring artists of his generation, looked towards established figures for inspiration. The work of fellow Swiss artist Louis Moilliet (1880-1962), known for his travels with Paul Klee and August Macke and his sensitive use of color, particularly in watercolor, provided one source of influence. Müller absorbed Moilliet's approach to color, learning how it could be used not just descriptively but also emotionally.

Furthermore, the powerful, psychologically intense art of the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863-1944) resonated deeply with the emerging Expressionist sensibilities across Europe, and Müller was no exception. Munch's pioneering use of distorted forms, symbolic color, and raw emotional honesty offered a compelling model for artists seeking to break free from academic constraints and explore the inner world. These early influences helped shape Müller's artistic direction as he moved towards a distinctively Expressionist idiom.

The Transformative Encounter with Kirchner

A pivotal moment in Albert Müller's life and artistic development occurred in 1923. Through exhibitions or mutual connections within the art world, he met and forged a deep, lasting friendship with Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938). Kirchner, a leading figure of German Expressionism and a founding member of the seminal group "Die Brücke" (The Bridge), had relocated to Davos, Switzerland, in 1917, seeking refuge and recovery from physical and psychological trauma exacerbated by World War I.

This friendship proved immensely stimulating for Müller. Kirchner's established reputation, radical artistic vision, and charismatic personality exerted a powerful influence. Müller's painting language underwent a significant transformation under Kirchner's mentorship and through their artistic dialogue. He embraced a bolder palette, employing vivid, often non-naturalistic colors and strong contrasts to heighten the emotional impact of his work. His brushwork became more dynamic, and his forms more simplified and angular, aligning with the core tenets of Expressionism.

Thematically, Müller often turned to his immediate surroundings, frequently depicting landscapes around Basel and the Ticino region where he spent time. His family members, particularly his wife Anna and their twin daughters Judith and Kaspar, became frequent subjects, rendered with both intimacy and expressive force. This focus on personal life echoed Kirchner's own practice. The relationship was one of mutual respect; Kirchner, in turn, valued Müller's talent and energy, creating portraits of Müller and his family, capturing the intensity of their bond.

Founding the "Rot-Blau" Group

The burgeoning Expressionist movement in Switzerland needed platforms and collective energy to thrive. Recognizing this, Albert Müller became a driving force behind the formation of the artists' group "Rot-Blau" (Red-Blue) in Basel on New Year's Eve 1924. He co-founded the group with fellow artists Hermann Scherer (1893-1927), a sculptor and painter also influenced by Kirchner, and Paul Camenisch (1893-1970), who would later become known for his contributions to Swiss modernism.

The "Rot-Blau" group emerged partly out of a shared dissatisfaction with the conservative art establishment in Basel and a desire to create better opportunities for exhibiting avant-garde art. They sought to inject new energy into the local scene, promoting a distinctly Swiss form of Expressionism characterized by intense color, vigorous execution, and often rustic or emotionally charged subject matter. Kirchner, though based in Davos, acted as a kind of spiritual mentor to the group, his influence clearly visible in their collective output.

Müller was central to the group's activities during its initial, most dynamic phase. "Rot-Blau" organized exhibitions, challenging public taste and advocating for a modern artistic vision. Their collective identity, though short-lived in its original configuration due to the early deaths of both Müller and Scherer, played a crucial role in establishing Expressionism as a significant force within Swiss art history, paving the way for future generations of modern artists in the region.

Artistic Style and Diverse Oeuvre

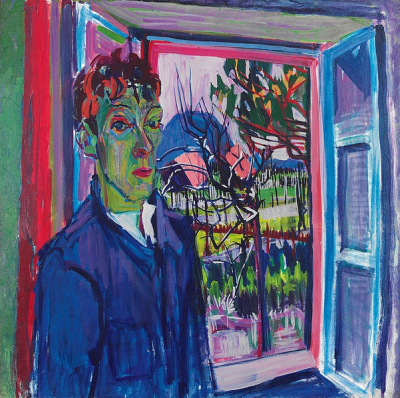

Albert Müller's art is quintessentially Expressionist, prioritizing subjective experience and emotional expression over objective reality. His style is marked by its chromatic intensity; he employed brilliant, often unmixed colors applied with energetic brushstrokes. Forms are frequently simplified, sometimes distorted or angular, to convey feeling rather than precise anatomical or topographical accuracy. A sense of immediacy and raw vitality pervades his work.

While primarily known as a painter, Müller was versatile in his choice of media. His paintings, often executed in oil on canvas or board, tackled landscapes, nudes, and intimate portraits, particularly of his family. These works capture the dynamism of nature and the psychological presence of his sitters through bold color harmonies and dynamic compositions.

Beyond painting, Müller continued to explore other avenues. His early training in glass painting left a mark, and although perhaps less numerous than his paintings, his works in this medium likely shared the same expressive qualities. He was also active as a graphic artist, producing drawings and prints, likely woodcuts or linocuts, which mirrored the strong lines and contrasts found in his paintings. The directness and inherent expressive potential of printmaking techniques like the woodcut resonated strongly with Expressionist aesthetics, as seen in the work of Kirchner and other Die Brücke artists like Erich Heckel (1883-1970) and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (1884-1976).

Müller also ventured into sculpture. His sculptural works primarily consisted of wood carvings, often roughly hewn and retaining the texture of the material. Significantly, many of these sculptures were painted, integrating his vibrant color sense into three dimensions. This practice of polychroming sculpture was also characteristic of Kirchner and Scherer, further highlighting the shared artistic concerns within their circle. Unfortunately, specific titles and creation dates for many of Müller's individual works are not readily available in standard art historical summaries, a common issue for artists whose careers were cut short and whose estates may not have been comprehensively catalogued immediately.

Context within European Expressionism

Albert Müller's work, while distinctly Swiss, belongs firmly within the broader context of European Expressionism, a diverse movement that swept across the continent, particularly in Germany, Austria, and Scandinavia, in the early 20th century. Expressionism was not a single monolithic style but rather a shared impulse among artists to express inner emotional and psychological states, often reacting against the perceived materialism and spiritual emptiness of modern industrial society, as well as the constraints of academic naturalism and Impressionism's focus on fleeting visual effects.

Müller's connection to Kirchner places him in direct dialogue with German Expressionism, specifically the Die Brücke group. Founded in Dresden in 1905, Die Brücke artists, including Kirchner, Heckel, Schmidt-Rottluff, and briefly Emil Nolde (1867-1956) and Max Pechstein (1881-1955), sought to create a 'bridge' to a more authentic, vital future through art characterized by intense color, distorted forms, and often jarring perspectives, drawing inspiration from sources like medieval German woodcuts, African and Oceanic art, and artists like Munch and Vincent van Gogh. Otto Mueller (1874-1930), another Die Brücke member (note the similar surname but different artist), focused on lyrical depictions of nudes in landscapes.

While Die Brücke represented one major current, another significant German Expressionist group was Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), centered in Munich around Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) and Franz Marc (1880-1916). Their approach often leaned more towards spiritual abstraction and symbolic color, though they shared the fundamental Expressionist goal of conveying inner meaning.

In Austria, figures like Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980) and Egon Schiele (1890-1918) developed their own intense, psychologically probing forms of Expressionism, often focusing on portraiture and the human figure with raw, sometimes disturbing honesty.

Within Switzerland itself, Müller and the Rot-Blau group were key figures, but they built upon the work of earlier Swiss modernists who had engaged with color and emotion, such as Cuno Amiet (1868-1961) and Giovanni Giacometti (1868-1933) – father of the famous sculptor Alberto Giacometti – both of whom had absorbed Post-Impressionist ideas. Even the monumental, Symbolist-influenced work of Ferdinand Hodler (1853-1918) contributed to a climate receptive to expressive artistic forms in Switzerland. Müller's contribution was to synthesize these influences, particularly the potent impact of Kirchner, into a vibrant, albeit brief, flowering of Expressionism in Basel.

Untimely Death and Lasting Legacy

Albert Müller's promising career was tragically cut short. In 1926, at the height of his creative powers and only 29 years old, he succumbed to cholera. His death, followed shortly by that of his friend and Rot-Blau colleague Hermann Scherer in 1927, dealt a severe blow to the momentum of the Expressionist movement in Basel.

Despite the brevity of his working life, Müller's impact was significant. He produced a substantial body of work in just a few years, demonstrating remarkable energy and a rapidly maturing artistic vision. His role in founding "Rot-Blau" provided a crucial focal point for the avant-garde in Basel, fostering a sense of community and shared purpose among like-minded artists. His close relationship with Kirchner facilitated a vital exchange between German and Swiss Expressionism.

Kirchner deeply felt the loss of his young friend and protégé. In 1927, he organized a memorial exhibition for Müller at the Kunsthalle Basel, a testament to their bond and Kirchner's belief in Müller's talent. This exhibition helped to solidify Müller's reputation posthumously.

Today, Albert Müller is recognized as one of the most important Swiss Expressionist painters. His legacy is preserved primarily in museum collections. The Kunstmuseum Basel (Museum of Fine Arts Basel) holds a significant part of his artistic estate, making it the primary institution for studying his work. His paintings, drawings, prints, and sculptures can also be found in other Swiss collections and internationally. For instance, institutions like the Kunsthalle Bonn in Germany and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in the United States have acknowledged his significance by including his work in their collections or exhibitions focused on Expressionism.

While Müller himself did not live to see the rise of Nazism in Germany, the movement he belonged to, Expressionism, was later vilified by the Nazi regime as "degenerate art" ("Entartete Kunst"). Many of Müller's friends and influences, most notably Kirchner, suffered persecution, had their works confiscated from German museums, and faced immense hardship. Kirchner himself tragically took his own life in 1938. Although Müller's work was primarily in Switzerland, the fate of Expressionism under the Nazis underscores the politically charged environment in which this art existed and the courage required of its practitioners. Müller's art stands as a testament to the vibrant, emotionally charged creativity that the forces of totalitarianism sought to suppress.

Conclusion: An Intense Flame

Albert Müller's life was short, but his artistic contribution was intense and significant. In less than a decade of mature work, he established himself as a central figure of Swiss Expressionism. Fueled by his innate talent, his studies, and transformative encounters with artists like Louis Moilliet, Edvard Munch, and especially Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, he developed a powerful visual language characterized by bold color, dynamic form, and emotional depth.

His co-founding of the "Rot-Blau" group provided a crucial catalyst for the avant-garde in Basel, creating a platform for a distinctly Swiss take on Expressionism. His diverse output across painting, printmaking, sculpture, and glass painting reveals a restless creative energy. Though overshadowed internationally by his mentor Kirchner and other giants of German Expressionism, Müller holds a secure and important place in Swiss art history. His work continues to be admired for its vitality and its poignant reflection of an artist burning brightly, albeit briefly, during a pivotal moment in modern European art. His legacy endures in the museum collections that preserve his intense and vibrant vision.